Should You Do Isolation Lifts to Build Muscle?

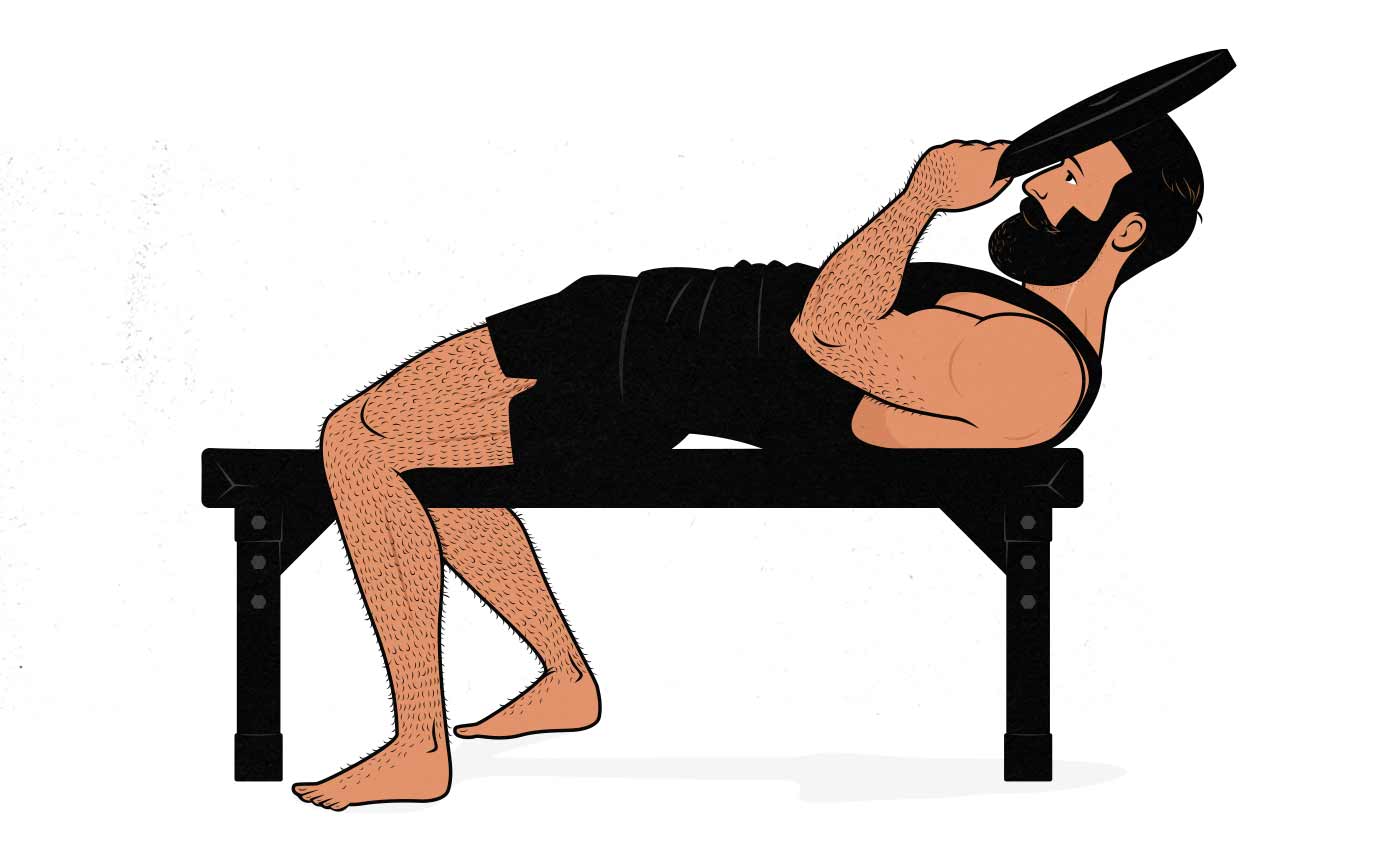

Isolation lifts, also known as accessory or single-joint exercises, are smaller lifts that are designed to “isolate” certain muscles. It’s a bit of a misnomer. No exercise works just a single muscle group, but isolation lifts can certainly be quite effective at emphasizing certain muscle groups. For example, the barbell bench press is used to gain size and strength in the chest, shoulders, and triceps, whereas the skull crusher is used to emphasize the triceps.

There are two popular ways of training for muscle growth. The first style of training is a descendant of strength training, and it focuses heavily—often exclusively—on the big compound lifts. These are the programs built around the squat, bench press, and deadlift, often with some overhead pressing and barbell rowing added in afterwards. We see this in programs like Starting Strength and StrongLifts 5×5, as well as a number of other popular programs that claim to be good for gaining both size and strength.

The second style of training is popular among casual bodybuilders, and it focuses more heavily on isolation lifts, sometimes at the cost of compound lifts. This is the style of training where people might use the leg press as their main lower-body movement, but will also be doing leg extensions, hamstring curls, and calf raises.

The more popular opinion is that compound lifts are better at stimulating muscle growth, and in a general sense, that’s true—they stimulate more overall muscle growth. But for many of the muscles in our bodies, isolation lifts are better. In fact, some muscles are only stimulated by isolation lifts.

Introduction

What Are Compound & Isolation Lifts?

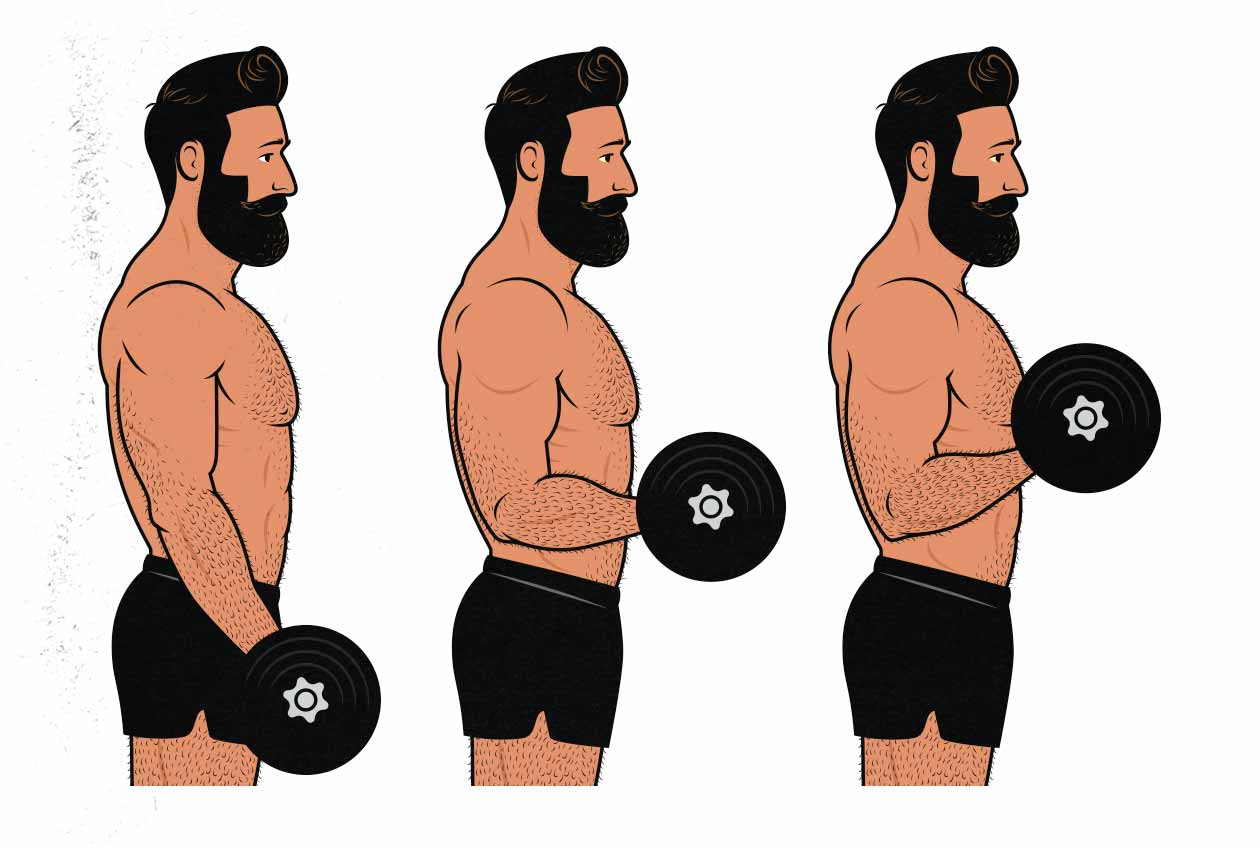

There are different ways of defining compound and isolation lifts. To some, all that matters is how many joints are being worked. A biceps curl moves at just the elbow joint, making it an isolation lift, whereas a row moves at both the elbow and shoulder joint, making it a compound lift.

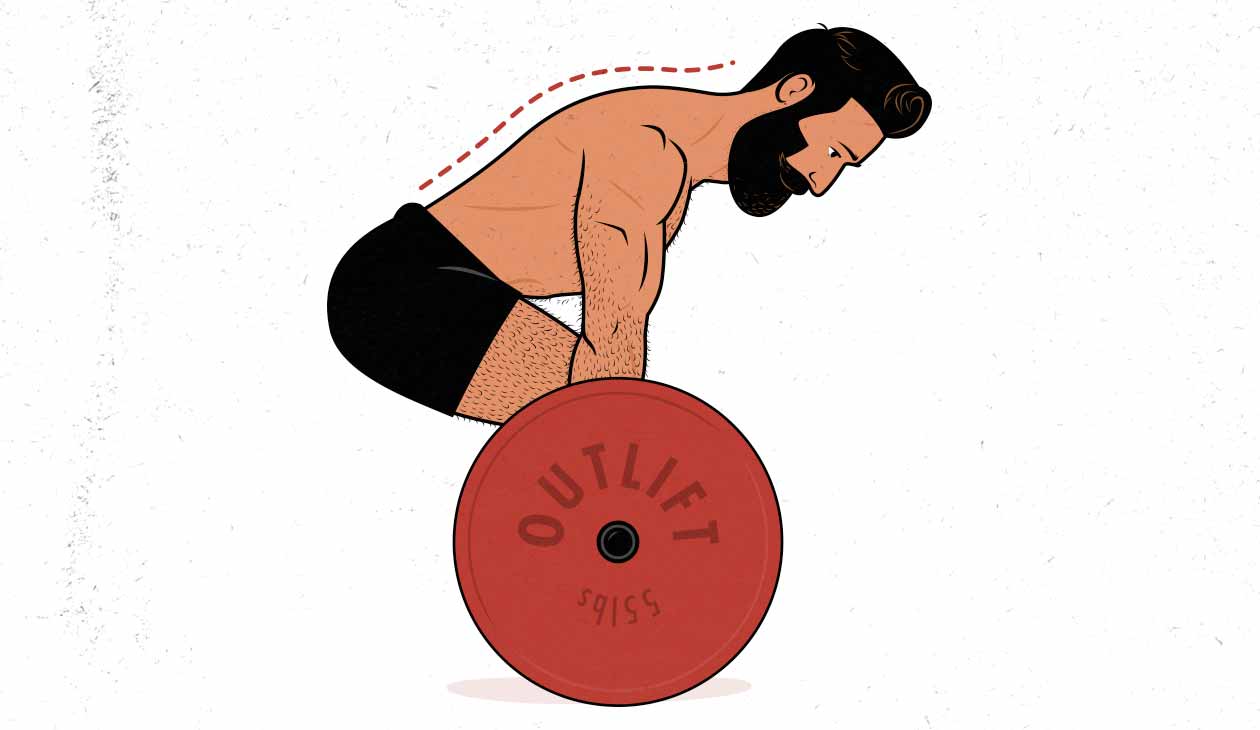

But that definition lacks some nuance. A Romanian deadlift moves at just the hips, but it’s a big lift that works our hamstrings, glutes, spinal erectors, traps, and forearms. Does that make it an isolation exercise? I would argue, no. It’s clearly a bigger compound lift.

As a result, I think it’s better to define compound and isolation lifts like so:

- Compound Lift: a bigger lift designed to train a general movement with the goal of bulking up many different muscles at once. This includes multi-joint movements like the chin-up (for our biceps, upper backs, and abs) as well as single-joint movements like the Romanian deadlift (for our hamstrings, glutes, traps, and grip).

- Isolation Lifts: a smaller lift designed to train a specific muscle. This includes multi-joint lifts like the pull-up (for our upper backs) and single-joint lifts like the biceps curl (for our biceps).

There’s a spectrum here, too. Squats and deadlifts are huge compound lifts that engage most of the muscle mass in our bodies, whereas upright rows are a much smaller compound lift designed to work just our shoulders, traps, and biceps. The same is true with isolation lifts. Barbell curls can be fairly heavy and demand quite a lot of stabilization from our upper backs, whereas wrist extensions are a tiny lift that works just a few small muscles.

But as a general rule, compound lifts are designed to work all of the muscles involved in a general movement (pushes, pulls, squats) whereas isolation lifts are designed to work a specific muscle (biceps, triceps, side delts).

Isolation Lifts Versus Compound Lifts

Most of us know that the compound lifts are the foundation of a good bulking program. They engage the most muscle mass, allow us to lift the heaviest weights, and stimulate the most muscle growth. Looking beyond just muscle growth, they’re also the best lifts for developing general strength, they put the largest stress on our bones and connective tissues, and they even do a good job of challenging our cardiovascular systems. In fact, with just five compound lifts, we can stimulate almost every muscle in our bodies and build truly impressive physiques.

But, unbeknownst to many, isolation lifts have quite a few notable advantages of their own:

- Our necks, forearms, abs, and calves are barely stimulated by compound lifts. To bulk them up, most people need to train them with isolation lifts.

- Some muscles contribute relatively little to the big compound lifts and will become disproportionately small if we don’t train them directly. For example, the long heads of our triceps won’t see much growth if we only train them with the bench press and overhead press.

- Some muscles are worked through a very small range of motion during compound lifts. For example, because our biceps cross both our elbow and shoulder joints, they barely change length when doing chin-ups.

- Isolation lifts are quick and easy to do, allowing us to add in a ton of training volume in a short amount of time without causing much extra fatigue. For example, isolation lifts make it easy to use drop sets, supersets, and circuits.

Without a smart use of isolation lifts, we won’t grow as quickly, some muscles will lag behind, some muscles won’t grow at all, and we’ll be at greater risk of developing nagging aches and pains in our joints. Even our strength can suffer.

Why Compound Lifts Stimulate So Much Muscle Growth

To build bigger muscles, we need to challenge them enough to provoke growth. The heavier the lifts are, the more muscle mass they engage, and the larger the range of motion, the more overall muscle growth we’ll stimulate. That’s why deep front squats, conventional deadlifts, chin-ups, and overhead presses are so great at stimulating muscle growth—they’re heavy lifts that work a ton of muscle mass through a large range of motion. And so if our goal is to gain the most muscle mass possible, these big lifts give us the biggest bang for our bulk.

For a specific example, if we do a heavy set of bench press, we’re engaging the muscle mass in our chests, shoulders, and triceps. And if we bring that set within a couple of reps of failure, we’ll stimulate plenty of muscle growth, especially in the bigger chest and shoulder muscles that contribute most to the lift.

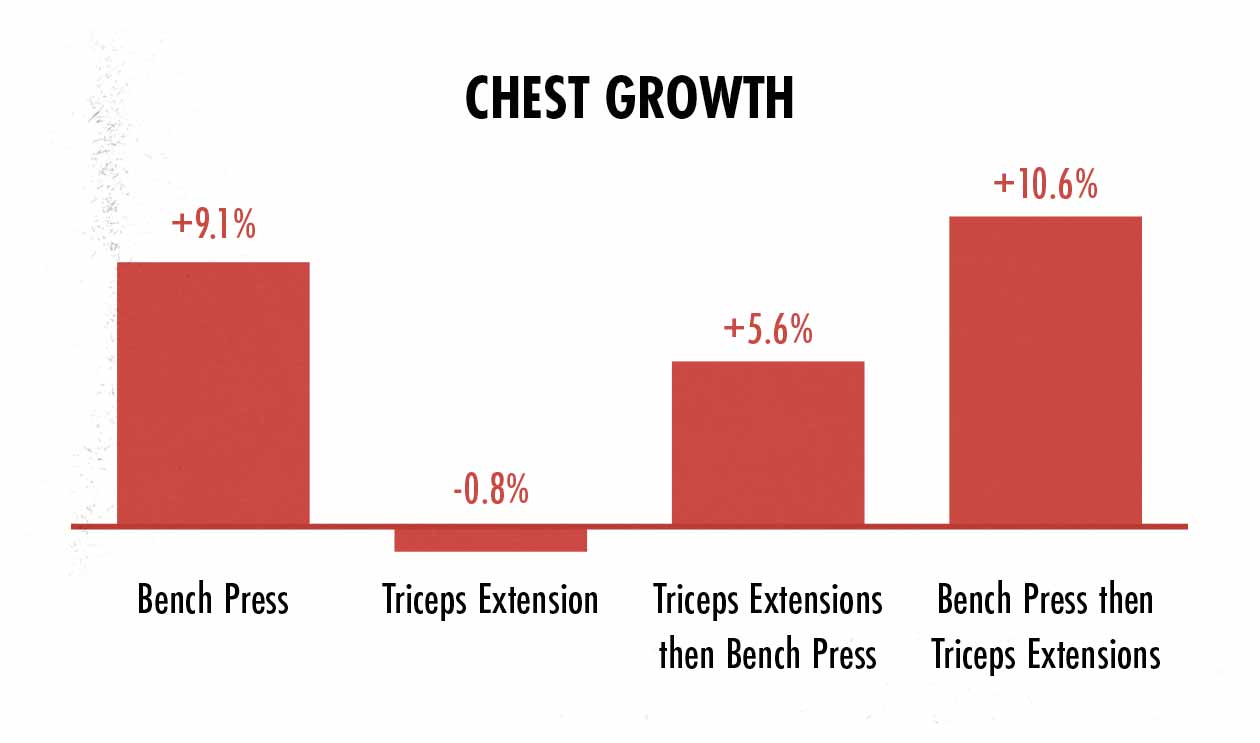

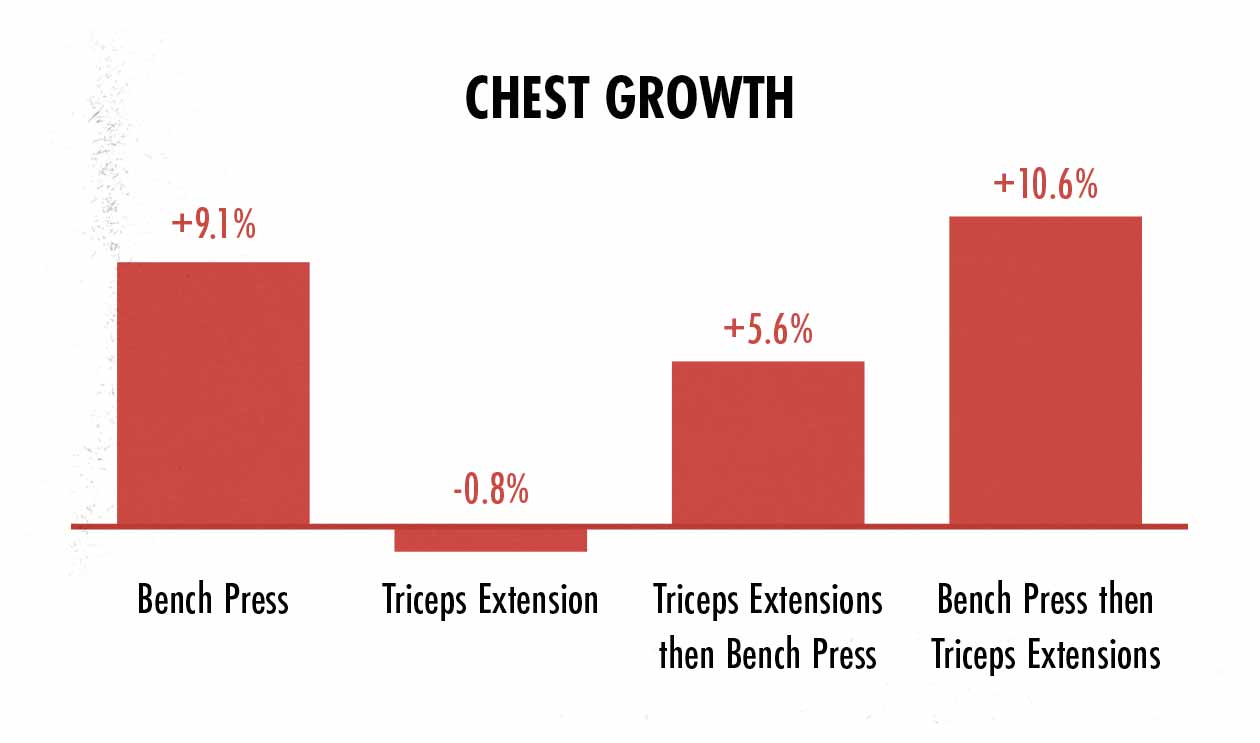

If we look at our chest growth after ten weeks of doing just the bench press and compare it against a program that also included triceps extensions, we see that the bench press stimulates a ton of muscle growth on its own, and the benefit of adding in an isolation lift is relatively small (study):

What’s happening here is that when we do the bench press, our chests are often the limiting factor. And so when we bring a set of the bench press close to failure, we’re bringing our chests close to failure, provoking muscle growth.

If we add an isolation lift to that, especially a that doesn’t emphasize our chests, it’s no surprise that the extra lift doesn’t stimulate much extra growth in our chests. And besides, if we wanted a higher training volume for our chests, we could simply do more sets of the bench press.

This same principle holds true with using squats to bulk up our quads, the overhead press to bulk up our shoulders, deadlifts to bulk up our posterior chains, and chin-ups to bulk up our backs. Those tend to be the limiting factors on those lifts, and so we’d expect them to see great growth. And if we want even more growth, we can simply do more sets of those exercises.

However, even the very biggest compound lifts don’t maximally stimulate every single muscle in our bodies—not even close.

Why Isolation Lifts Are So Important

Some Muscles Only Grow From Isolation Lifts

As we mentioned above, to make a specific muscle bigger, we need to challenge it enough to provoke muscle growth. The problem is, compound lifts don’t challenge every muscle, and they certainly don’t challenge our muscles equally. When we take a set of the bench press near failure, our chests are typically our limiting factor, and so we’ll stimulate plenty of growth in our chests. However, even after going all the way to failure, some of the secondary muscles might not have been sufficiently challenged, and so they won’t grow.

If we think of our abs when doing chin-ups, yes, they’re quite active all through the lift. But how close to failure are our abs by the time we finish a set of chin-ups? Not very. Or what about our hamstrings during squats? Or our lats during deadlifts? These muscles are active, but they aren’t being challenged. And unless they’re being sufficiently challenged, they won’t grow.

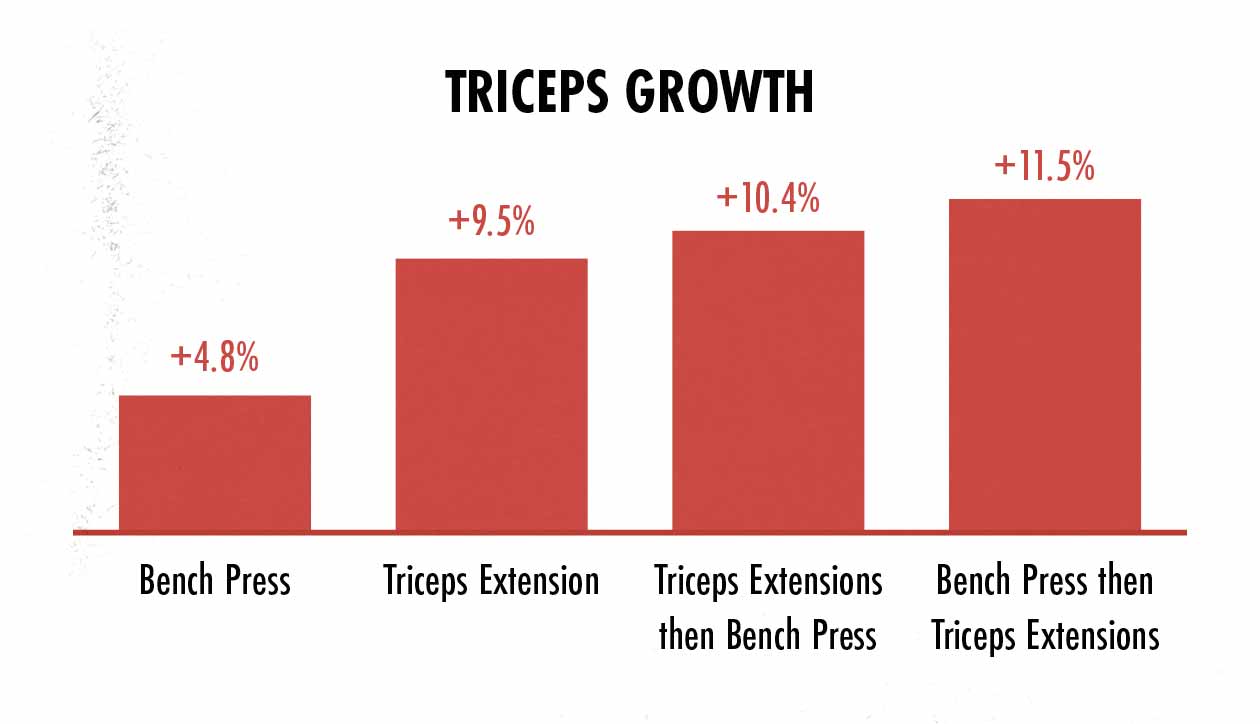

For an example of that, we can look at the triceps growth in that same ten-week bench press study that we mentioned above:

We see a small amount of triceps growth from doing the bench press, but we get almost double the amount triceps growth from doing just triceps extensions. In this case, an isolation lift is twice as good as the compound lift at stimulating muscle growth in our triceps, proving that compound lifts aren’t always better at bulking up our individual muscles.

Furthermore, most of the triceps growth from the bench press is in our lateral heads (an elbow extensor), whereas most of the growth from the triceps extensions is in our long heads (which also helps to extend our shoulders). The two different lifts are training two different heads of our triceps, showing us that if we want to build triceps that are muscular overall, we need a combination of both lifts.

Now, of course, we can’t exactly do triceps extensions instead of the bench press anyway. Triceps extensions won’t stimulate growth in our chests. So, of course, we need both the bench press and triceps extensions if we want to build muscle in both muscle groups. And if we do that, the lifts synergize. Doing the bench press followed by triceps extensions results in the most chest growth and the most triceps growth, and it gives us balanced growth in all of our muscle heads.

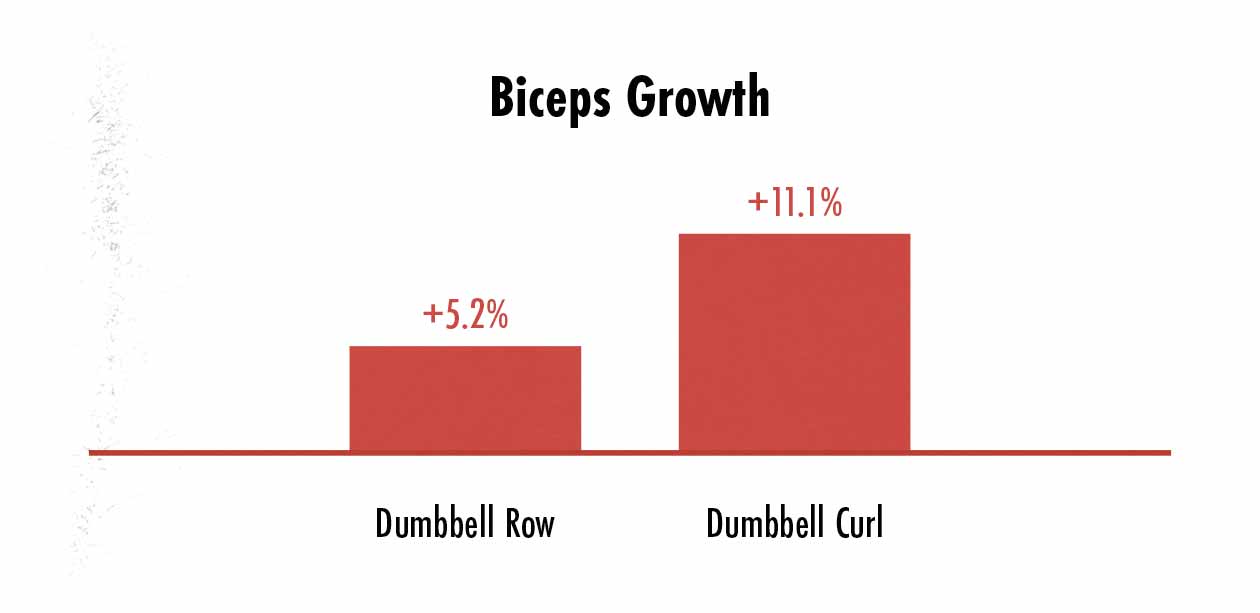

For another example of compound versus isolation lifts, we can look at a study by Mannarino et al comparing dumbbell rows (compound) with dumbbell curls (isolation) for biceps growth:

With both exercises, the participants used an underhand grip that was designed to involve the biceps, but the curl still stimulated twice as much biceps growth.

The case for isolation lifts gets even more compelling when we consider that some muscle groups aren’t stimulated by the big compound lifts at all. Our necks, for example, aren’t trained by any of the big lifts. Yes, deadlifts train our upper traps, but not a single compound lift stimulates our neck extensors or flexors, and so our necks will stay thin until we add in dedicated neck training:

The cost of isolation lifts, of course, is that our workouts get longer. We need to spend some time doing triceps extensions after we finish our bench pressing. However, the nice thing about isolation exercises is that because they’re lighter, they don’t tend to be very metabolically taxing, and so we don’t need to rest very long between sets.

If we’re willing to spend fifteen extra minutes working out, we can do a quick circuit of triceps extensions and biceps curls, or neck curls and neck extensions. Or maybe at the end of another workout, we even toss in some quick forearm curls and extensions. That way we’re growing the muscles that aren’t being properly stimulated by the big lifts.

In fact, even if we aren’t willing to spend any extra time working out, we may want to make room for isolation lifts by swapping them in for compound lifts. For example, instead of doing six sets of bench press, we could do four sets of bench + two sets of triceps extensions. We’d still expect to gain a similar amount of chest size, but we’d also be bulking up our triceps.

For an example of that, in a study on squats, researchers compared the muscle development of participants doing just squats with participants doing squats, leg presses and leg extensions. The training volume was equated, so both groups of participants did the same total number of sets for their quads, and as a result, both groups got equal quad growth. However, the participants doing the three different quad exercises saw more proportional growth in all four heads of their quads. Plus, because the sets of isolation exercises were lighter, their workouts were shorter and less fatiguing. And, believe it or not, the group that traded out sets of squats for isolation lifts even gained more squat strength.

So if we want to bulk up all of our muscles, not just the prime movers in the compound lifts, then it pays to follow up those compound lifts with isolation lifts for the muscles that are being left behind. And even if we want balanced growth in our prime movers, it pays to train those prime movers with a variety of different lifts.

Isolation Lifts for Regional Hypertrophy

We’ve already covered how some heads of our muscles are only challenged by isolation lifts. An example of that is how the long heads of our triceps don’t grow from pressing, just from triceps extensions. This clearly shows that if we want to build full and balanced muscles, we need to include a smart mix of both compound and isolation lifts. However, there’s another idea that’s popular among bodybuilders: regional hypertrophy.

For example, it’s true that using a narrower grip when bench pressing is better for bulking up our upper chests, whereas using a wider grip tends to be better for bulking up our mid and lower chests. These different variations target different muscle fibres, after all. But what about our inner versus outer chest? Those are the same muscle fibres. Can the same muscle fibres grow in some regions but not others?

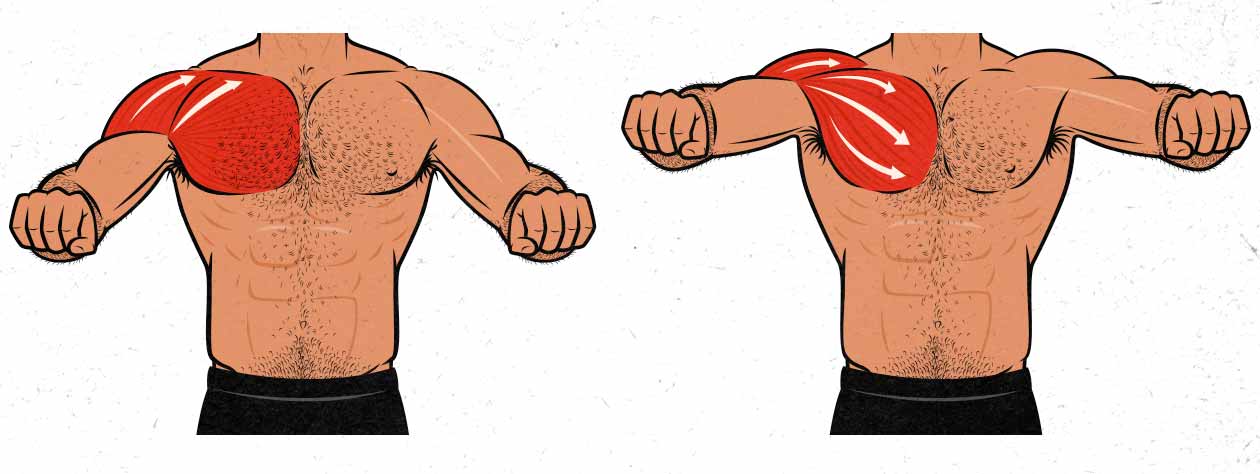

Different lifts have different strength curves. Some are hardest at the bottom of the lift when our muscles are stretched, such as the bench press, whereas others are hardest at the top of the lift when our muscles are contracted, such as the cable fly. These lifts are both challenging our mid chests, but they’re challenging our mid chests at different parts of the range of motion. This is where the controversy begins.

Some experts argue that we should use a variety of different strength curves to ensure that we’re bulking up the different regions of our muscles. For example, perhaps the bench press is better at bulking up the outer chest because it challenges our pecs in a stretched position, whereas the cable fly is best for bulking up our inner chest because it challenges our pecs in a contracted position. However, there’s no evidence to support that conclusion, and it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense mechanistically.

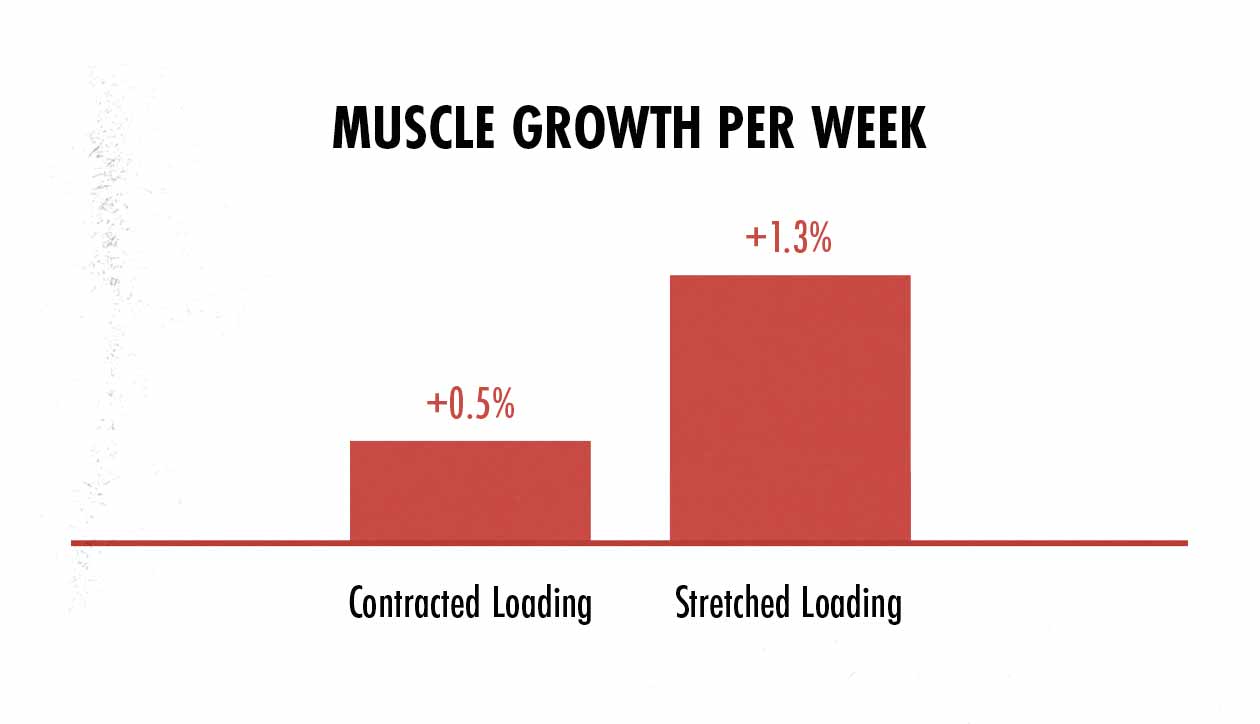

The evidence that we have shows that most of the time it’s simply better to focus on challenging our muscles in a stretched position (study). So instead of choosing a cable fly to train our chests in a contracted position, better to choose a dumbbell fly to challenge our chests in a stretched position, even if we’re already training that same strength curve with the bench press. That way we stimulate more muscle growth all through the muscle fibres we’re training.

However, there may indeed be some muscle groups where regional hypertrophy comes into play. With our ab muscles, for example, there are different compartments running up and down (we may have six distinct ab bulges, say), and it seems like some exercises are indeed better at targeting those different compartments. Hanging leg raises and reverse crunches may be better for our lower abs, whereas crunches may be better for our upper abs.

Isolation Lifts for General Strength

If we talk about strength as powerlifters do, where our strength is defined by how much we can squat, bench press, and deadlift for a single repetition, then we could make a strong case for specificity. We could argue that the best way to improve our low-bar squat strength is to spend more time low-bar squatting, less time doing isolation lifts.

There’s already a flaw in that line of thinking. We’ve already talked about the study showing that doing a mix of different lifts for our quads is better for improving our squat strength than doing just squats, even when training volume is matched. We gain more squat strength by spending less time squatting and more time doing isolation lifts. So we know that doing isolation lifts can improve our strength on the big compound lifts.

There’s a bit of nuance here, though. Most people are limited by their quad strength when squatting, so it makes sense that prioritizing quad growth with isolation lifts is an effective way to increase our squat strength. If we were doing other isolation lifts, such as good mornings or hip thrusts, we might not see that same increase in squat strength because those muscles (our glutes and spinal erectors) weren’t limiting us when squatting.

So it’s more accurate to say that if our goal is to improve our strength at the big compound lifts, then we should do those big compound lifts to train all of the relevant muscles, and then we should also include some isolation lifts for the muscles that are limiting our performance. Here are some examples:

- Squat: most people are limited by their quad strength when squatting, so the best way to speed up strength gains is to add more quad isolation work.

- Bench press: most people are limited by their chest strength, so the best way to build a bigger bench press is to add in extra chest work.

- Deadlift: most people are limited by either their hip or spinal erector strength, so the best accessory lifts are the ones like good mornings, Romanian deadlifts, and barbell rows, which train both the hips and spinal erectors to varying degrees.

However, I also want to challenge that definition of strength. Unless we’re powerlifters—and most of us aren’t—then there’s no reason to think that our general strength should be defined by the rules of the specific sport of powerlifting (or Olympic lifting, or strongman competitions, or etc).

I would argue that general strength should be defined by our strength on a wide variety of movements and in a wide variety of rep ranges. I think our 10RM chin-up strength is just as relevant as our 1RM squat strength. More controversially, I even think that lifts like curls and triceps extensions are an important part of general strength.

So to summarize, I think the best definition of general strength is our strength at a wide variety of movements in a wide variety of rep ranges. And the most effective way to build that kind of strength is to train a wide variety of lifts in a wide variety of rep ranges.

How to Combine Compound & Isolation Lifts

The most important thing to understand when combining compound lifts with isolation lifts is that we’re trying to give every muscle a chance to be the limiting factor—we’re trying to bring every muscle within a couple reps of failure at some point in our workout routine.

Let’s go back to the study that measured muscle growth with the bench press and triceps extensions. If we look at the participants who did triceps extensions first and the bench press second, they both saw similar amounts of triceps growth, but we see that their chest growth got cut in half:

What’s happening here is that the triceps extensions tired out their triceps, so when they went to do the bench press afterwards, their triceps failed before their chests did. This means that their triceps failed on the triceps extensions and then failed again on the bench press. But their chests never got a chance to go near failure.

If we look at the group who did the bench press and then the triceps extensions, we see maximal muscle growth in both the pecs and triceps. Why is that? It’s because the bench press brought their chests to failure, but their triceps were still fresh. So they added in triceps extensions afterwards, giving their triceps the chance to push near failure. By the end of the workout, they’d challenged both muscle groups enough to provoke maximal muscle growth.

This is the general principle we want to build into our entire workout routines. We want to start with our compound lifts, see which muscles aren’t being fully stimulated by them, and then add in isolation lifts to fill in those gaps.

Here’s how that might play out with the big five compound lifts:

- The Front Squat: the limiting muscle in the front squat is usually our quads, so we could add in glute bridges for our glutes, good mornings for our spinal erectors, or calf raises for our calves.

- The Bench Press: the limiting muscle in the bench press tends to be the chest (mid pecs), so we could add in skull crushers, triceps pushdowns, or triceps kickbacks for the shorter heads of our triceps. We may want some extra work for our upper chests, too, so we might want some incline pressing in our workout routines.

- The Deadlift: the limiting muscles in the deadlift are usually our hips, grip, or spinal erectors, so we might want to add in Romanian deadlifts for our hamstrings and rows for our lats and mid traps.

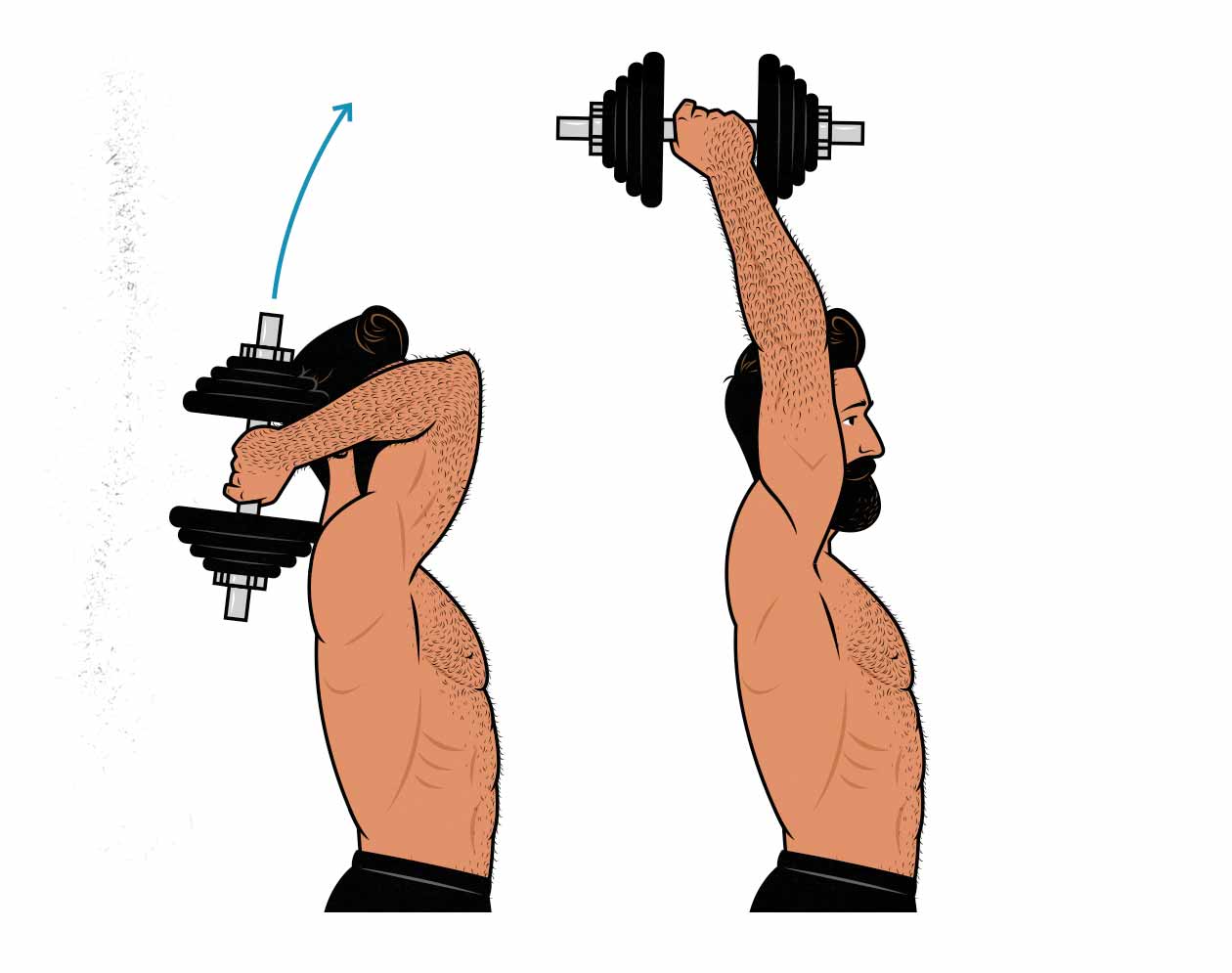

- The Overhead Press: the limiting muscle in the overhead press is often our shoulders (anterior deltoids), so we might want to add in some overhead triceps extensions for the long heads of our triceps.

- The Chin-Up: the limiting muscle in the chin-up is often our lats, so we might want to include some curls for our biceps and some face-pulls for our rear delts.

There’s some individual variation here, too. Quite a lot, actually. Different people will fail different lifts in different ways. Some people fail the bench press because their shoulders give out, others fail because their chests give out. That’s often why guys have stubborn or lagging chests. They expect the bench press to bring their chests close to failure, but it doesn’t, and they don’t have any isolation lifts to plug that hole. Their chests never get fully stimulated, and so their chests don’t grow.

Because of these differences between individuals, once we get beyond a beginner level and once we start to notice which muscles are being built by our compound lifts, it can really help to customize our routines so that our compound and isolation lifts combine in a way that suits us.

There also some muscle groups that aren’t stimulated all that intensely by any of the compound lifts:

- The neck muscles: the deadlift will bulk up our upper traps quite well, but we should also include some neck curls and extensions for our neck extensors and flexors (such as our sternocleidomastoid).

- The abs: chin-ups do a decent job of stimulating our rectus “six-pack” abs, but they’re unlikely to be brought close enough to failure to stimulate robust growth. We might want to add in some hanging leg raises or reverse crunches.

- The forearms: lifts like the deadlift train our grip strength, and those muscles are in our forearms, but the bigger muscles in our forearms are the flexors and extensors. To build muscular forearms, we usually need reverse curls, wrist curls, and wrist extensions.

Now, that might sound like a lot of work, having to do all of the big compound lifts, and their accessory lifts, and then even more lifts for our necks, abs, and forearms. However, keep in mind that we don’t need to bulk up every muscle group at once. There’s nothing stopping us from spending a few months focusing more on some muscles, then switching our emphasis to bring up the other ones.

And with some of the smaller muscle groups, like our necks, abs, and forearms, we might be able to spend a few months focusing on them, and then never really need to worry about training them again. We can rely on the compound lifts to more or less maintain their size with the small amount of ancillary stimulation they get.

Key Takeaways

Over the years, multiple similar studies have been conducted, and every single one found that adding in isolation lifts produced extra growth (study, study, study, study, study, study). Greg Nuckols, from Monthly Applications in Strength Sport, pooled the stats of those studies and found that, on average, including isolation lifts in our bulking routines caused 27% more muscle growth.

The interesting thing, though, is that isolation lifts are more important for some muscle groups than others. Our mid chests may get near-optimal growth just from the bench press, whereas our upper chests often need an incline or narrow-grip bench press, and our triceps need triceps extensions. By including a wider variety of lifts, we get, say, 27% more growth overall, but most of that extra muscle is in our triceps and upper chests.

So if we want to maximize muscle growth in all of our muscles, we can build the foundation of our routines out of the big compound lifts and then stack isolation lifts on top (study), perhaps rotating through those isolation lifts over time.

We can start our workouts with the big, heavy, tiring compound lifts to ensure that we’re efficiently building a large amount of muscle overall. Then we can squeeze in some relatively quick isolation lifts afterwards to bring up the muscles that are sure to lag behind: our biceps, triceps, neck muscles, forearms, and so on.

We tried to build this principle into our guides for each of the five big lifts. They start with an explanation of how to get the most out of the big compound lifts, and then we cover the best isolation lifts to do afterwards.

The other takeaway is that it’s better to use a smart mix of both compound and isolation lifts, but that we don’t need to do every single isolation lift, or even train every single muscle, all at the same time. There’s nothing wrong with shifting our training emphasis every few months, gradually cycling through the various muscles and accomplishing our goals a few at a time.

Or, if you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. If you liked this article, you’ll love the full program.

This is one of my favorite articles you have written Shane! You guys are always putting up quality content. I have a question for you though regarding the forearm isolation lifts. Personally my forearms have grown rather proportionally with the rest of my body going through the B2B workout program(thanks for that!) just based off all the grip work and I suspect primarily from the deadlifts. But you’re saying in this article that grip strength doesn’t grow your flexors and extensors which happen to be the biggest muscles in the your forearm? I’ve never done dedicated forearm work with iso lifts before, so does this mean I’m leaving alot of potential gains on the table? And are you at risk of over working forearms if you need them fresh for your next workout?

It also sounds like it’s a good idea to throw in calf raises on a squat day should I just do a circuit of standing and sitting raises?

Honestly I think forearms training could warrant an article on its own, after all they are one of the most badass looking muscles and they are what helped Popeye easily open up those spinach cans!

Many thanks, Alec

Thank you, Alec! That means a lot 🙂

We took into account that most people doing the Bony to Beastly program want bigger forearms. We don’t include forearm curls and extensions, but we include a variety of lifts that train the forearm flexors and extensors isometrically, as well as lifts that train the elbow flexors (such as the brachioradialis). So, for example, biceps curls are often enough to train the forearm flexors at first. Reverse curls train the brachioradialis very well, but they also work the extensors a decent amount.

Eventually, you’ll need more dedicated forearm isolation lifts if you want to continue bulking up your forearms. But at first, they’re often worked quite well with other lifts. I think that’s why your forearms have been growing well so far without any wrist curls and extensions.

The other thing we want to be mindful of with novice lifters is that if we beat up your hands, grip, and forearms too much, we can interfere with your workout performance. It’s hard to lift vigorously with raw, tired hands. We don’t want to overdo the stress on your joints, either. So, yeah, it’s certainly possible to overdo it with forearm training, especially early on.

Yes! We’ll post a full article on forearm training soon. It’s already mostly written 🙂

And if you want bigger calves, then yeah, it’s a good idea to do some calf raises. Standing calf raises work quite well. Remember to raise your toes up on something so that you can get a deep stretch on your calves at the bottom. You probably want to do at least 3 sets per workout and train them at least 3 times per week. They need quite a lot of volume to grow.

(A study came out last month comparing training the hamstrings with bent versus straight legs. Training them with straight legs stimulated more growth because the hamstrings got a better stretch at the bottom of the range of motion. I think the same would be true with calves. Better to train them with straight legs to get a better stretch. I’m not sure that seated calf raises would be needed.)

I hope that helps!

Thank you for the thought out response, I always enjoy seeing the reasoning behind the programming. I’ll have to add those calf raises to my workouts aswell. Looking forward to that forearm article!

Thanks again

My pleasure, man. Good luck!

Im confused on the studies you link. You stated that multiple studies show adding isolation movement builds more muscle when combined woth compound exercises, but the first link was to European Journal of Sport Scinec which concluded that “that trained men can save time not including SJ in their routines and still achieve optimal results”. Can you please clarify how this proves isolation exercises are needed?

Hey Mark, I’m not claiming that isolation exercises are needed, just that they allow us to build muscle more quickly, especially in areas that aren’t properly stimulated by compound lifts, most of which are in our limbs.

We always try to include all relevant studies, including ones that have a null finding or opposite finding. With these studies on isolation lifts, a lot of them fail to reach statistical significance, so even though the groups doing isolation lifts saw better growth, it didn’t reach statistical significance, and the authors report a conclusion like the one you’re quoting. That doesn’t mean that we can use the study as proof that isolation lifts help. After all, the study didn’t reach statistical significance. But it doesn’t disprove the idea, either. Still, to leave these studies out would be misleading, cherry-picking, you know?

So what we try to do is take all studies into consideration to form our conclusions. When we do that with isolation lifts, we do reach statistical significance overall, and the effect size is actually quite large. So it’s not so much any particular individual study that proves a benefit, but rather the entire body of evidence. As more research is published, the apparent benefit seems to be growing larger, too. (Especially since some of the studies coming out of Barbalho’s lab, which found no benefit, seem to be fraudulent and may soon be retracted.)

So to summarize, isolation lifts aren’t needed, but based on the sum of current evidence, they do seem to speed up overall muscle growth by upwards of 20%. And then if we look specifically at the muscle heads that benefit most from the isolation lifts, such as the long heads of our triceps, the benefit becomes quite a bit more dramatic.

Wow! A friend of mine just showed me this page and since then I’ve been reading it like when you discover a new Netflix series.

I want to share some doubts I’m facing. By the way, context: 29 years old, did bodybuilding and jiujitsu for about 7 years, and in the last 2 years I’ve been doing CrossFit.

Well, I do CrossFit 3x/week and I want to add some hypertrophy exercises for biceps, lats, and rear deltoids. But I’m struggling. When is the optimal time to do it? after the WODs or on another day?

I’m sharing your material with my friends for sure!!!

Hugs from Brazil

Hey Leonardo, thank you! And greetings from Cancun 🙂

I’m not sure what Netflix series you’re thinking of, but I’ve heard that discovering this site is rather like discovering Tiger King.

If it were me, I’d do some chin-ups, biceps curls, and rear delt flyes on rest days. Maybe 3–4 sets of chin-ups, 2–3 sets of curls, and 2 sets of rear delt flyes. There’s nothing wrong with doing a bit of hypertrophy training right after CrossFit, but those workouts are already quite rigorous, so by doing your it on a separate day, you’ll feel a bit fresher and have more energy for it.

You have some studies linked to the article that concluded that “there is no significant benefit to SJ exercises with MJ exercises”. This is for both untrained men and trained men with 3+ years of body building experience. The same was for both trained and untrained women too according to the studies you linked. How does that prove that adding isolation exercises an addition to compound exercises are optimal? I would argue more volume and weight with compound exercises will work better. ACE did an EMG study and found the chin up had a higher bicep activation than the dumbbell curl. This is because you can load more weight for overload. I saw you also mentioned adding SJ to MJ exercises increased results by 20%, but I couldn’t find that anywhere. What source are you referring to? The most difference I found was .3% in additional muscle in Journal of Strength and Conditioning.

There was no benefit at all, not significant. I misquote.

Hey Jason, what we’re doing is taking the sum of all the relevant studies, not looking at any one study. All of the studies linked are fairly small, and though most showed an advantage to adding isolation lifts compared to compound lifts, they lacked the statistical power to make a conclusion. So what some researchers have done, such as Greg Nuckols, MA, is create a meta-analysis of all the research. That’s where we find the 20% benefit, and as more research comes out, that benefit seems to be increasing.

If you want examples of individual studies finding benefits, here’s one study comparing underhand dumbbell rows against dumbbell curls for biceps growth, finding twice as much biceps growth in the group doing curls. (Some of our upper back muscles grow just fine from rows, though, so it depends which muscles we’re talking about.)

Here’s another study comparing different combinations of the bench press and triceps extension. Again, twice as much triceps growth from doing triceps extensions instead of bench press, and even more growth when combining both together. (The chest grows just fine from the bench press, though, so again, it depends on which muscle we’re talking about.)

But the best way to approach this isn’t to give examples of the specific studies, it’s to look at the results from every study and see what the overall body of evidence indicates. In this case, we do indeed see a strong advantage for adding isolation lifts, but it seems more like 20–30% more growth rather than double. And isolation lifts aren’t needed for every muscle, just the muscles that aren’t being properly stimulated by compound lifts.

As for EMG studies, they can be good sometimes, and if that’s all we have, that’s all we have. But muscle activation doesn’t always perfectly indicate muscle growth. If we’re interested in muscle growth, better to look at studies comparing muscle growth. Fortunately, we have several of those available here. And for chin-ups versus curls for biceps growth, we have a full article on that here.

Great article, I was always suspicious of black and white advice that said no isolation lifts. I’m actually considering your intermediate program now as I’ve just gone in 4 months from 25% fat to 14% and built some muscle, so a successful recomp and looking to start bulking. And it was done with a mix of compound and isolation lifts, so see no reason to stop doing what works.

One of my favorite ways to program isolation lifts is into express workouts. Sometimes, I just don’t want to go to the gym. I can’t bring my self to do 4 compound movements. But I don’t want to lose momentum with another rest day, so I’ll do at home 5 sets of a big exercise and 5 supersets of two opposing isolation. Like 5 x dumbbell muscle clean and press (no push press), 5x seal row + dumbbell flys. 20 minutes done with a couple hundred dollars worth of home equipment and I haven’t entirely replaced my gym workout, but haven’t lost momentum either.

Congrats on dropping from 25% down to 14%, Patrick—that’s awesome!

I think that’s a great idea. Keeping up momentum is huge, and have those days where you spend more effort on those smaller movements is a great way to build those muscles and get better at those movements 🙂

Greg found a 27% improvement with isolation + compound but this is somewhat misleading. This group gained 3.8% on average compared to 3% on average for just isolation. With the results that close, I don’t think it is statistically significant, as indicated by a recent meta-analysis ( https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0000000000000720). Though, I still think adding isolation exercises results in more growth when it is possible to sufficiently isolate each head of a muscle, e.g. triceps and deltoids. If not, the overall growth would probably be similar between compound + isolation and just isolation, as indicated by most of the studies on bicep growth.