Min-Maxing Strength Curves for Hypertrophy

The best way to build muscle is to challenge our muscles through a large range of motion. Lifting through a large range of motion is a good start, but some parts of it might be easy, giving our muscles little resistance, and thus failing to provoke muscle growth. Other parts will be more difficult, giving our muscles the stimulus they need to grow. We call this the strength curve of the lift.

Conventional wisdom says that if a lift is similarly challenging throughout the entire range of motion, then the entire range of motion will stimulate muscle growth, and we’ll build far more muscle with every rep. And there’s some truth to that.

However, it’s not quite that simple, either. Some parts of the range of motion are more important than others. It’s important to choose lifts that challenge our muscles in a stretched position, but not so important for a lift to be difficult at lockout. It can also really help if a lift is heaviest where our muscles are strongest, allowing us to lift more weight through the entire range of motion.

In this article, we’ll talk about resistance curves, the strength curves of our muscles, the strength curves of various lifts, and how to build more muscle.

- The Four Strength Curves

- Factors That Affect A Strength Curve

- Which Factors Matter Most?

- How Important Are Strength Curves?

- The Importance of Challenging Our Muscles At Long Muscle Lengths

- The Best Strength Curves for Building Muscle

- Strength Curve Examples

- Do Exercise Machines Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

- Do Cable Machines Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

- Do Resistance Bands Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

- Does Accommodating Resistance Increase Hypertrophy?

- Key Takeaways

Disclaimer: This is me trying to explain and visualize what I’m still in the midst of learning. I’ll be updating this article over time as I learn more.

The Four Strength Curves

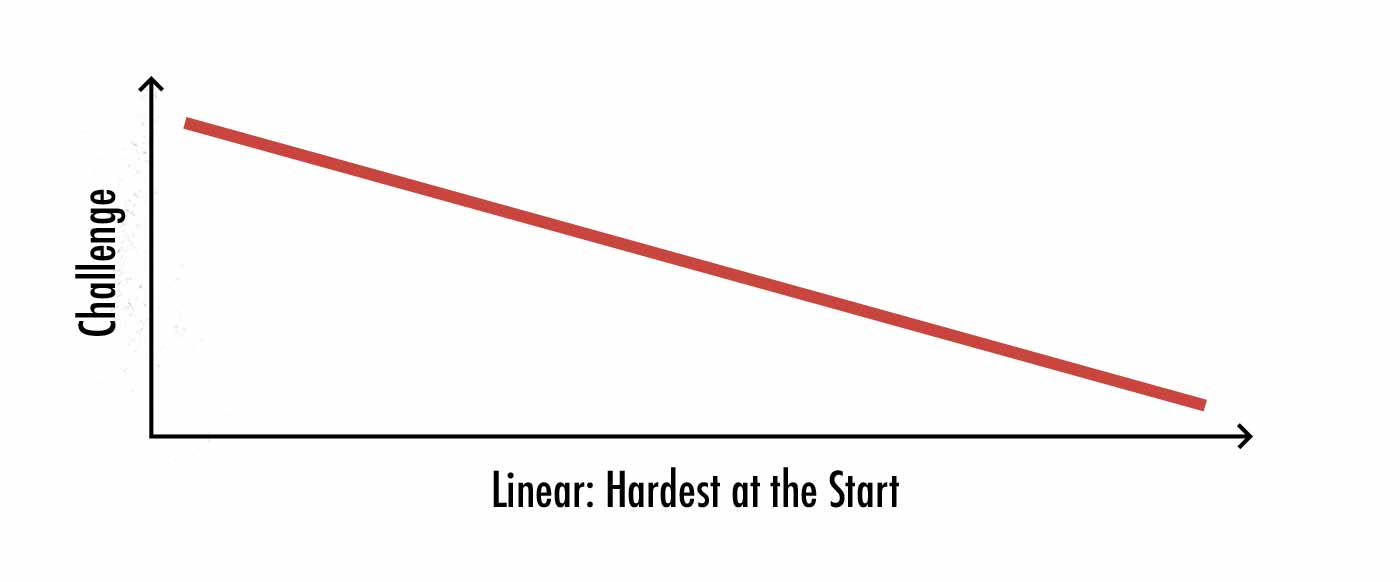

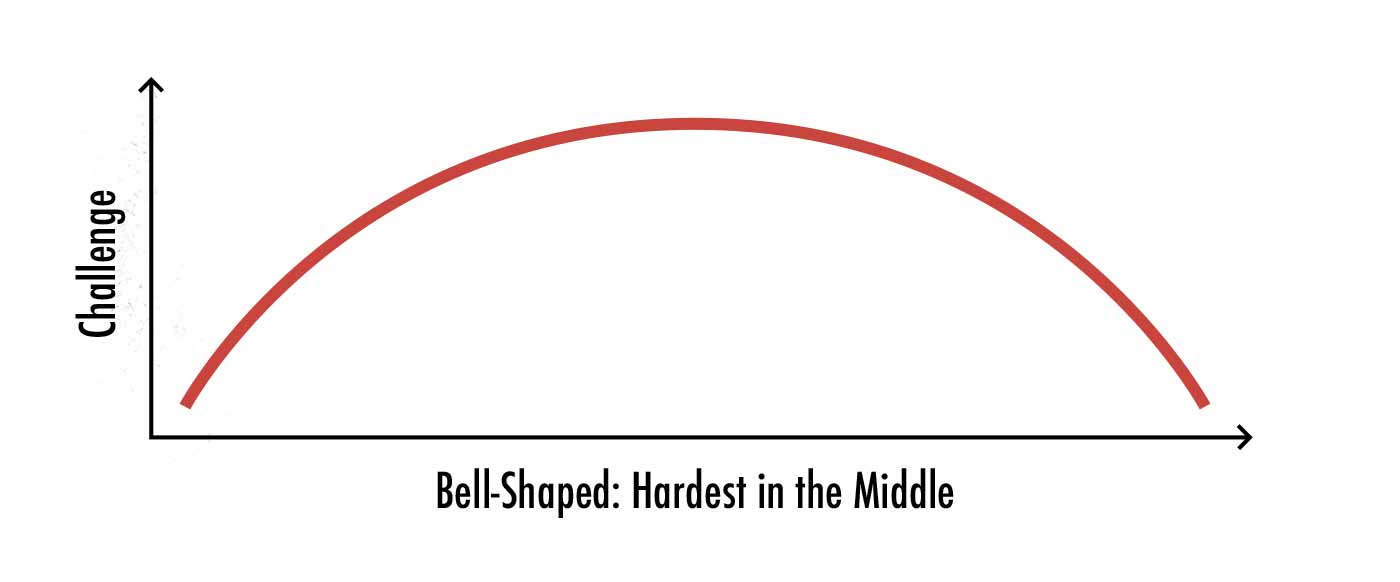

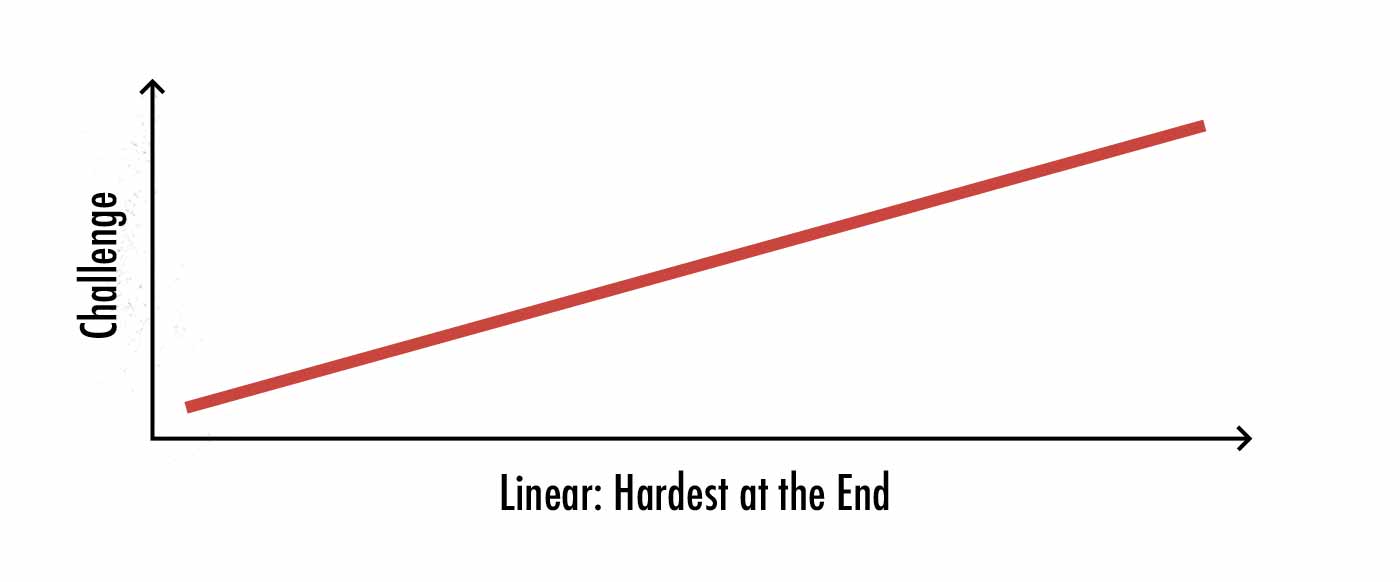

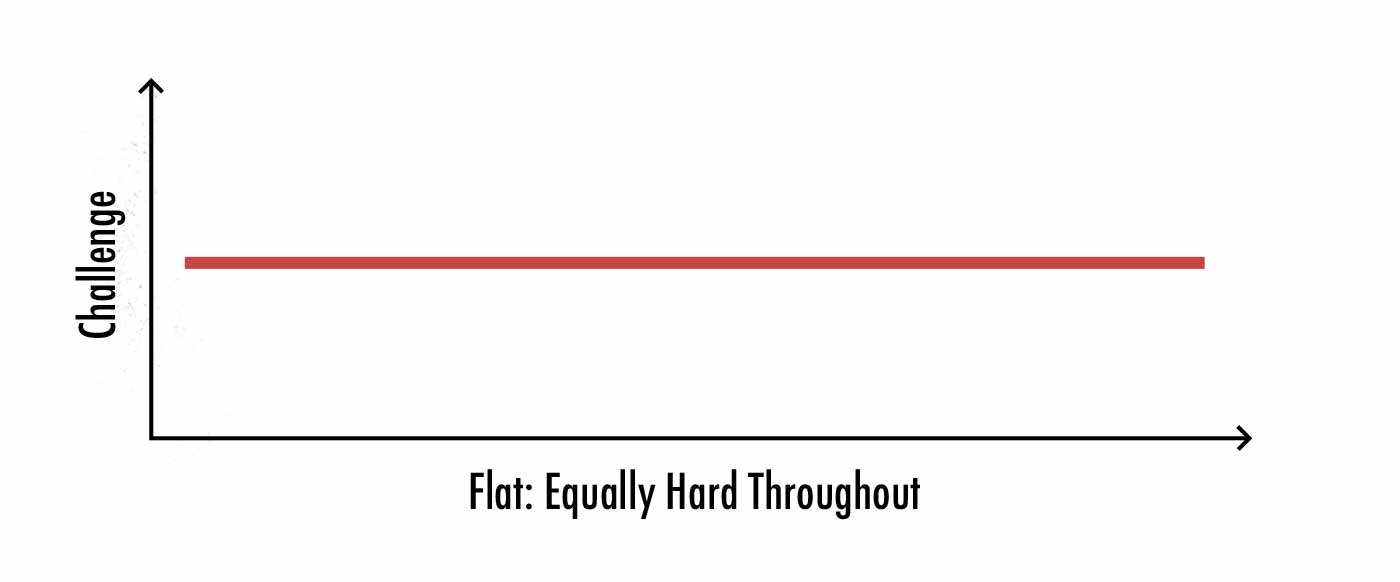

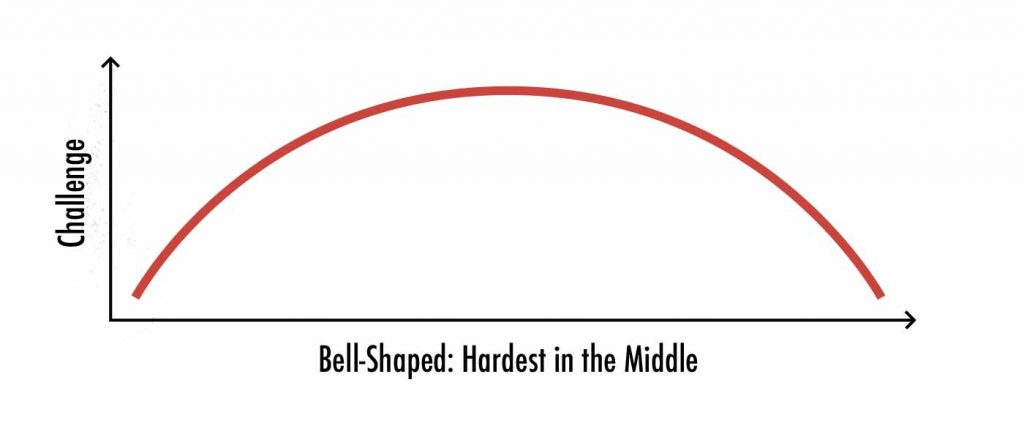

Okay, so, the first thing we need to do is talk about the different kinds of strength curves that we see when lifting weights. There are four different types of strength curve (source):

Hardest at the start (linear strength curve): the lift is hardest at the beginning or the end. Powerlifters will sometimes create linear strength curves by setting up in a sumo deadlift stance (hardest off the floor) doing wide-stance low-bar squats (starting the lift from the sticking point) or benching with a big arch and a wide grip (starting above the sticking point). In all of these cases, the lift is hardest at the beginning and then gets easier the further we lift the barbell. In theory, that’s an ideal strength curve for building muscle. In practice, though, it’s often accomplished by shortening the range of motion, removing the part of the lift where our muscles are stretched, and therefore destroying the benefit.

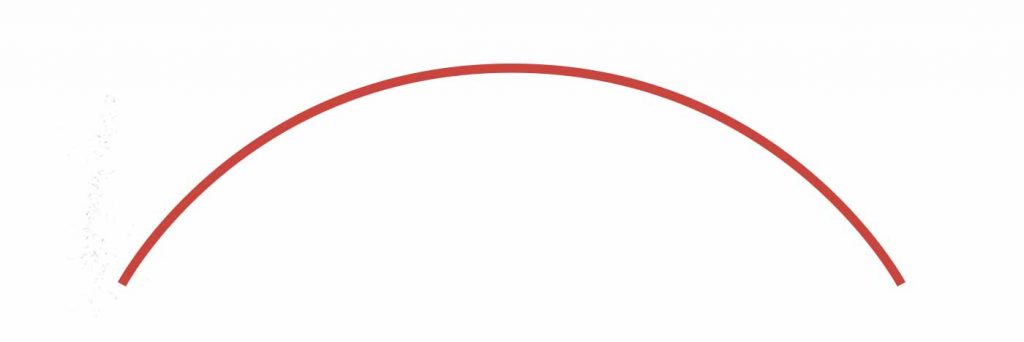

Hardest in the middle (bell-shaped strength curve): it’s common for barbell and dumbbell lifts to be hardest in the middle of the range of motion (when our limbs are horizontal). The barbell curl, the front squat, the bench press, and the overhead press all have bell-shaped strength curves. Our anatomy seems to be designed for this, and these lifts work quite well for building muscle.

Hardest at the end (linear strength curve): many pulling movements are notorious for being disproportionately hard at the very end of the range of motion. When doing a barbell row, it’s easy to lift the barbell off the ground but hard to touch it to our stomachs. When doing pull-ups, it’s easy to get the movement started but hard to bring our chests all the way up to the bar. This tends to be fairly bad for building muscle, but there are some ways around it.

Equally challenging throughout (flat strength curve): most people think that a flat strength curve is desirable for muscle growth, and there’s some truth to that, so many bodybuilding exercise machines are designed to flatten the curve. A t-bar row machine is a good example of a machine that corrects the strength curve of a barbell row.

As mentioned above, the conventional wisdom is that the flatter the strength curve is, the more our muscles will be challenged throughout the entire range of motion, and the more muscle we’ll build with every repetition. Flatter strength curves should also yield more versatile strength gains (because we grow equally strong through the entire range of motion).

The benefits of flat strength curves are fairly well known, so a lot of exercise machines and cable machines are built with the goal of creating a flat curve. If we look at a pec fly machine, for example, it has a fairly flat strength curve. It’s similarly challenging throughout the entire range of motion. It’s not perfect, but it’s a much flatter strength curve than the bench press or the dumbbell fly. And that’s great.

However, even though there’s truth to that conventional wisdom, there are three more factors to keep in mind:

- The part of the range of motion that’s the most challenging (the sticking point) tends to stimulate the most muscle growth. For example, at the sticking point of a wide-grip bench press, our chests are challenged more than our triceps, and so our chests will see more growth. (With a narrower grip, our upper chests and shoulders would be challenged more at the sticking point, and so they’d see more growth.)

- When our muscles are challenged in a stretched position, we get more muscle growth (study). For example, when we stretch out our chests at the bottom of a bench press, it stimulates a ton of muscle growth in our chests. On the other hand, our triceps aren’t stretched out by the end press, and so they don’t get this benefit.

- The more tension we can keep on a muscle throughout the lift, the more our muscles grow—maybe. This one is fairly speculative, but in theory, if we can keep constant tension on our muscles throughout the entire range of motion, we might be able to stimulate more muscle growth. Bodybuilders often preach the idea of keeping constant tensions on our muscles while lifting, and there’s some research to support that, but it’s too soon to say for sure how much it matters.

So, for example, you might hear that the dumbbell fly has a bad strength curve because it’s too easy at the top of the range of motion. Not so! It’s challenging when our pecs are stretched and where our pecs are strongest. The strength curve might not be flat, but it’s still a great curve for stimulating muscle growth. It may even be better than a flat curve.

Factors That Affect A Strength Curve

The Resistance Curve (External Moments)

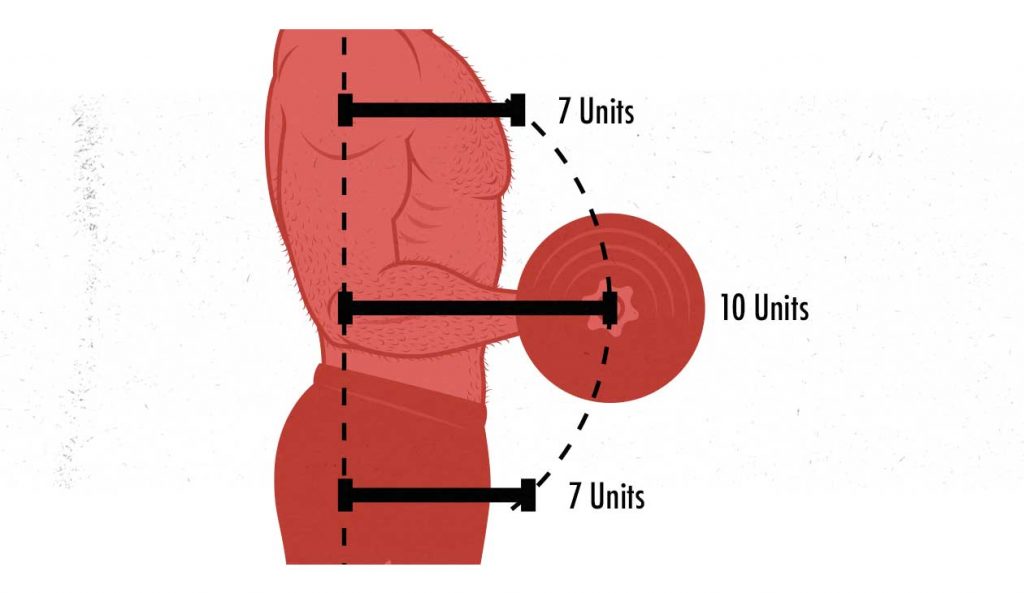

Alright, so, when we’re lifting weights, some parts of the range of motion are more challenging than others, and there are two things at play here. First, there’s the resistance curve:

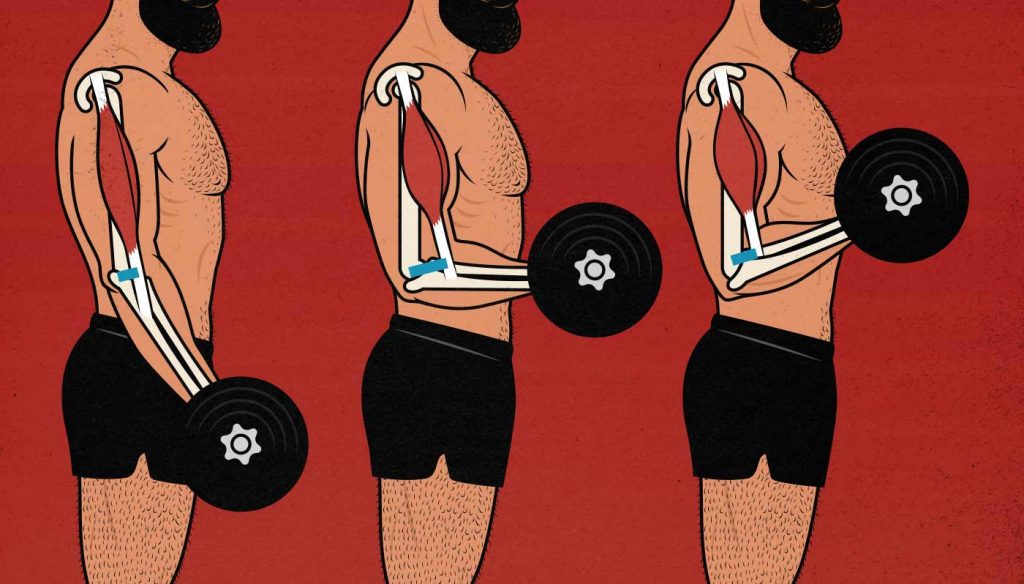

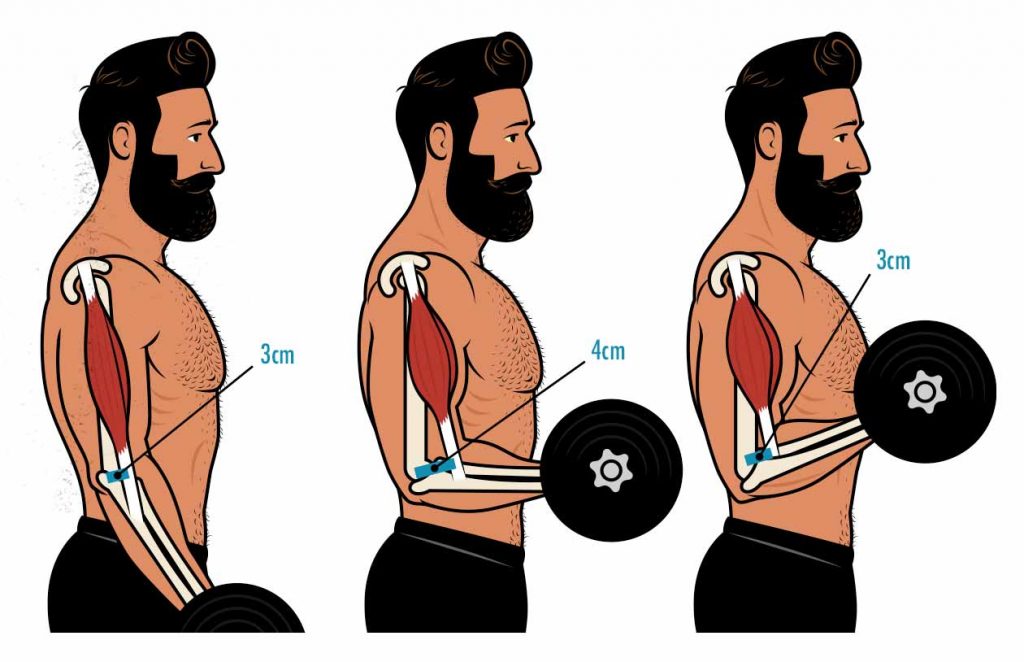

What we’re seeing here is that the lever (our forearms) has a moment arm that’s around 40% longer at the midway point than is it at the beginning, making the barbell around 40% heavier in the middle. That’s the resistance curve. And if we plot this resistance curve out, we get a bell-shaped curve, like so:

So with a resistance curve like this one, the issue is that the weight isn’t exerting much downward force at the beginning and the end of the lift. However, this is just the resistance curve. It doesn’t take into account that we’re stronger at different joint positions and muscle lengths.

Leverage (Internal Moments)

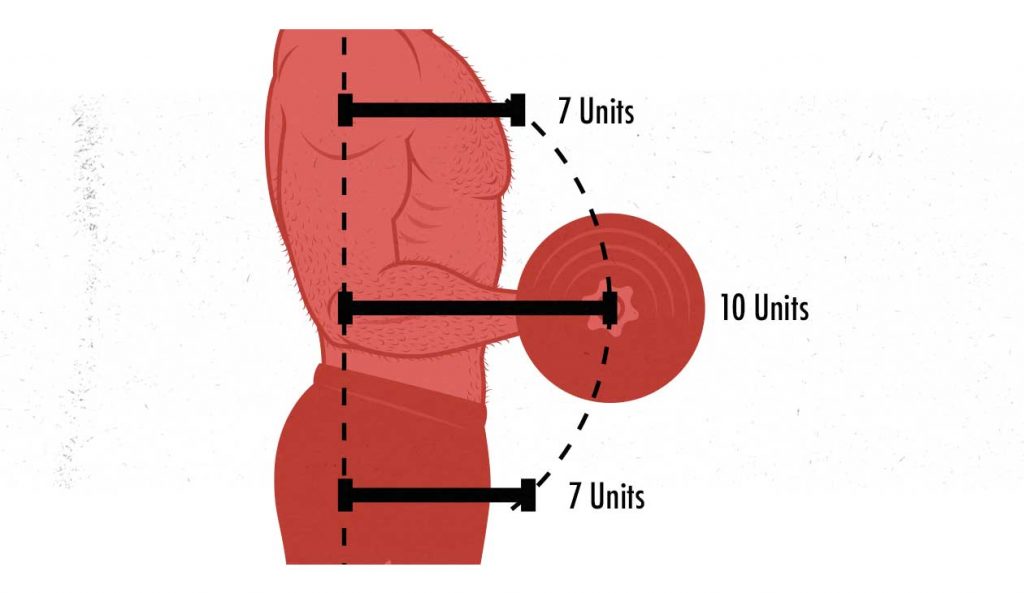

Next, there are our internal moments, where our muscles produce different amounts of force at different joint positions. Just like our limbs create external levers that make the weight feel heavier, our muscle insertions create internal levers that make the weight feel lighter.

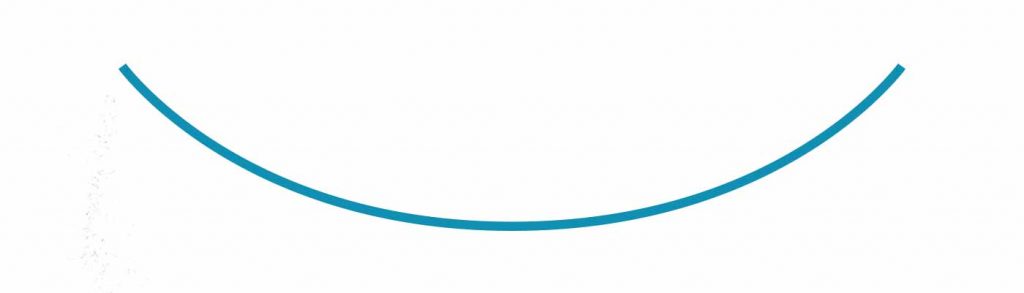

What we’re seeing here is that the internal moment arm between our elbows and biceps tendon is around 30% longer at the midway point than it is at the beginning, making us around 30% stronger in the middle. Our internal moment arms are our leverage.

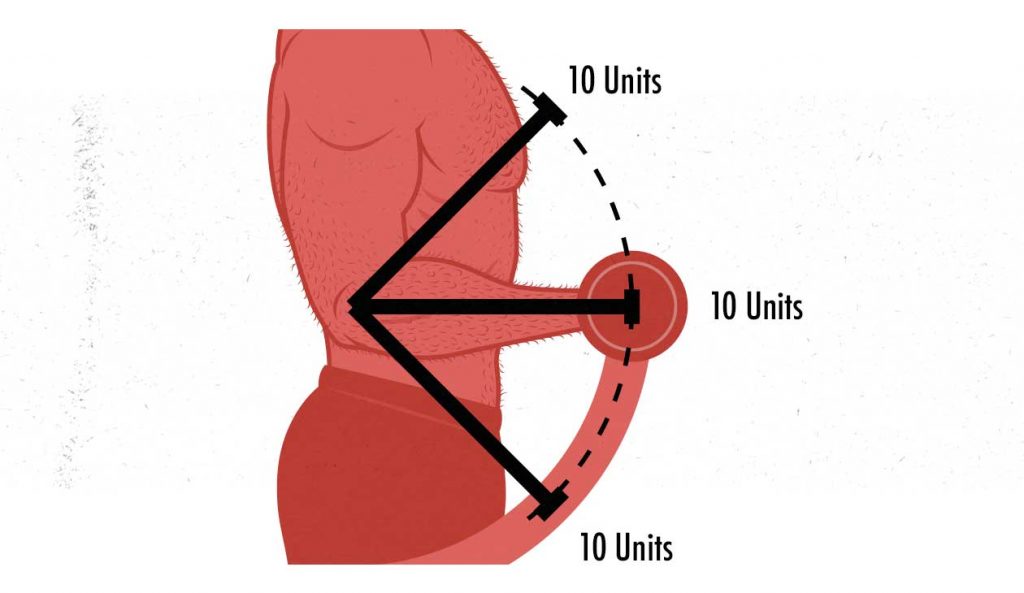

So now we have our resistance curve, like so:

And our strength curve, like so:

If we line up the resistance curve (external moments) with our leverage (internal moments), we start to get an idea of how challenging the lift will be at different parts of the range of motion. With the barbell curl, the resistance curve and the strength curve are aligned. We’re strongest where the weight is heaviest. Our internal moments almost cancel out the external moments:

Our muscle insertions help us overcome the resistance curve of, and yet we still fail at that midway point because the resistance curve is more dramatic than our strength curve. Our leverage helps, but we still have a sticking point where the external moments are longest. This is common. It’s the same in the squat, the bench press, and many other lifts.

That’s because most muscles, as with the biceps, are strongest somewhere in the middle of their range of motion. With most free weight lifts, that’s also where the weight exerts the most force on our muscles. These warring bell-shaped curves somewhat cancel each other out. And that’s good. It creates a flatter strength curve. That’s one of the reasons why free weights (dumbbells and barbells) are so good for stimulating muscle growth.

If we think about it, that makes sense that our bodies are naturally better at lifting rocks and logs than pulling on cables or applying torque to exercise machines. No surprise, then, that lifting barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells all tend to work our muscles pretty heartily, causing robust gains in size and strength.

The Length-Tension Relationship

The next thing to consider is the length-tension relationship. As a general rule of thumb, our muscles tend to be strongest at their natural resting length. So if you imagine yourself standing with your arms at your sides, that will give you a good idea of the positions where your muscles can exert the most force.

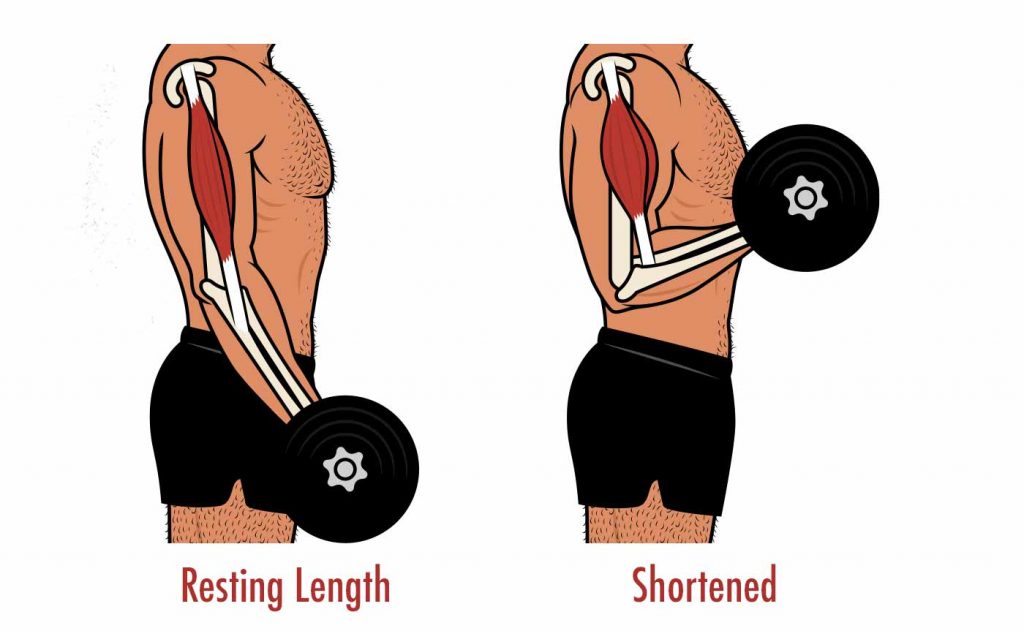

For example, in the barbell curl, our biceps are at their natural length at the beginning of the lift, which makes the beginning of the lift a little bit easier:

As we curl the weight up, our biceps shorten, and they lose some of their ability to produce force. This is why the end of a biceps curl tends to be harder than the beginning. This adds a new curve to factor in:

It’s a fairly modest curve. This isn’t a major factor. But it gets added into the strength curve of the barbell curl, tilting it upwards a bit:

The next aspect of the length-tension relationship is that our muscles are kind of like elastics. If we stretch them past their resting lengths, they snap back to their normal position without us even needing to exert any active force. This can be a real asset in some lifts, such as getting a stretch on our chests at the bottom of a bench press, a stretch on our hamstrings at the bottom of a deadlift, or a stretch on our quads at the bottom of a front squat.

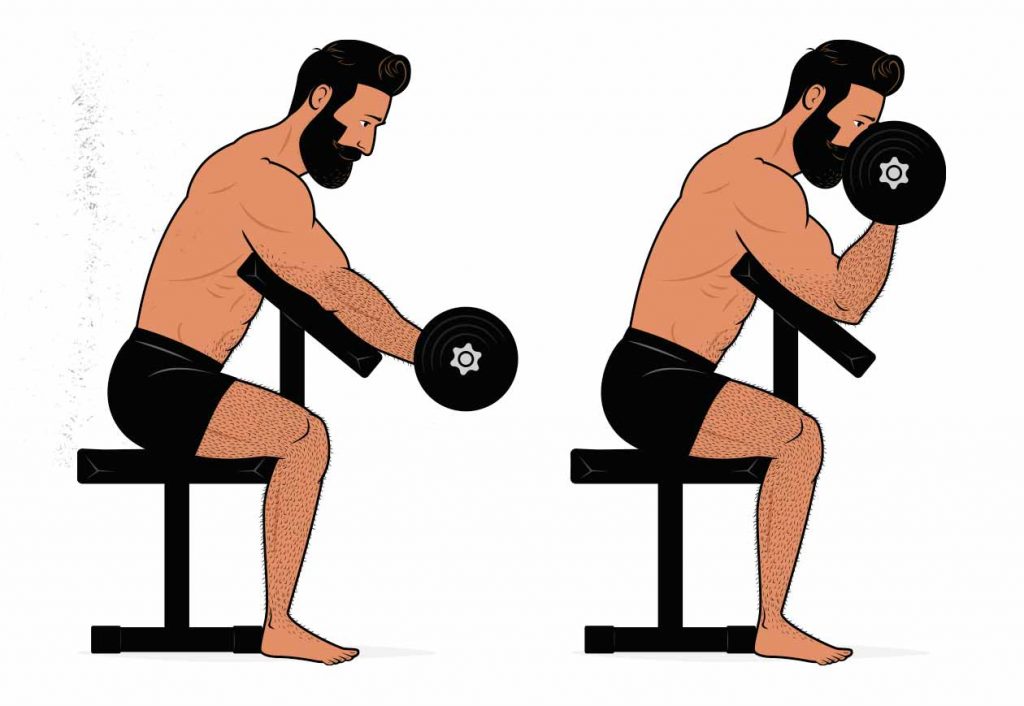

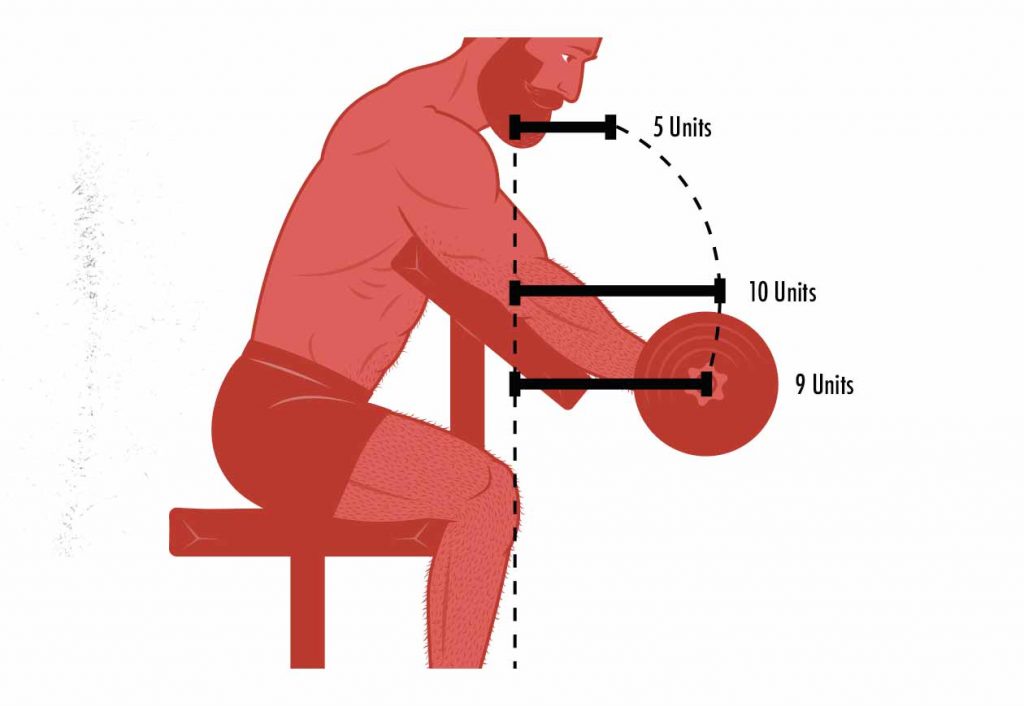

With biceps curls, you can make the exercise harder at the beginning of the range of motion by doing preacher curls, drastically improving the strength curve. You can improve the strength curve even more by doing lying biceps curls, which stretch your biceps at the shoulder joint.

Antagonist Interference

When we flex our biceps, we’re flexing both our biceps and triceps, locking our arms in a flex position. This is antagonist interference. Two opposing muscles fighting against each other.

In the barbell curl, the same thing can happen, albeit to a lesser degree. As we flex our biceps to bring the barbell up, our triceps might be pulling down somewhat, making the lift a bit harder. This may be a problem with some beginners, but over time, as our coordination improves, interference becomes fairly minimal.

For a more meaningful example, at the bottom of a squat, our hamstrings pull us down, meaning that our quads need to overcome not only the weight but also our hamstrings. And, in fact, our hamstrings have to work in order to keep our hips in the correct position. So a squat will always involve opposing muscle groups working against one another to keep us in the proper position. Even in the squat, though, this isn’t a major factor.

Momentum

Because the resistance curve is often easier at the beginning of a lift, and because our muscles are stronger when they’re stretched, most hypertrophy lifts are easier at the beginning than they are at the end:

- Front squat

- The bench press

- The conventional deadlift

- The overhead press

- The chin-up

- The barbell curl

- Triceps extensions

- The barbell row

What’s nice about a lift starting off easier is that if we lift as hard as we can right from the very beginning, we gain momentum that can help us drive through the sticking point, flattening the curve.

In the case of the barbell curl, there are some variations, such as the power curl, that put extra emphasis on gathering momentum, but even with a standard curl, it helps to accelerate the barbell upwards. This tilts the curve:

In other lifts, where the strength curve is more extreme than the curl, there can be even more emphasis on driving the barbell upwards. That’s why we have lifts like the push press and power row.

The benefit to using momentum is that if we start putting our full effort into the lift right from the very beginning, the lift becomes challenging through more of the range of motion, making it slightly better for building muscle. The cost, though, is that we need to decelerate towards the end. We aren’t trying to throw the barbell. And so the end of the lift becomes easier

Now, you might say, why are we trying to make the beginning of the lift harder and the end of the lift easier? That’s a good question. the answer is that some parts of the range of motion stimulate more muscle growth than others. We’ll talk about that in a second.

Which Factors Matter Most?

There are a few factors that affect the strength curve of a lift, but some are much more important than others. Here they are, listed in the order of importance:

- The resistance curve (external moments)

- Our leverage (internal moments)

- The length-tension relationship

- Antagonist interference.

- Momentum

The resistance curve has the largest impact on which part of the range of motion feels hardest (study), to the point where we almost don’t need to consider the other factors. For example, if we look at just the resistance curve of the barbell curl, we can already guess where the sticking point will be: in the middle.

The same is true with most lifts. The hardest part of the lift is when the external moment arms are longest. That tends to be when the lever is horizontal:

- The hardest part of the squat is when our thighs are horizontal.

- The hardest part of the bench press and overhead press is when our upper arms are horizontal.

- The hardest part of the chin-up (for our biceps) is when our upper arms are horizontal.

- Deadlifts get harder on our backs the more horizontal our torsos are.

- The hardest part of the barbell curl and triceps extension is when our forearms are horizontal.

- The hardest part of a wrist curl is when our hands are horizontal.

But that doesn’t mean that the other factors don’t matter. Quite the opposite. The more the other factors can help us overcome the resistance curve, the flatter it will become, the more parts of the range of motion will be challenging, and the more muscle we’ll build. Even though the resistance curve will overpower the other factors, the whole point is to fight it as well as we can. That’s how we best build muscle.

How Important Are Strength Curves?

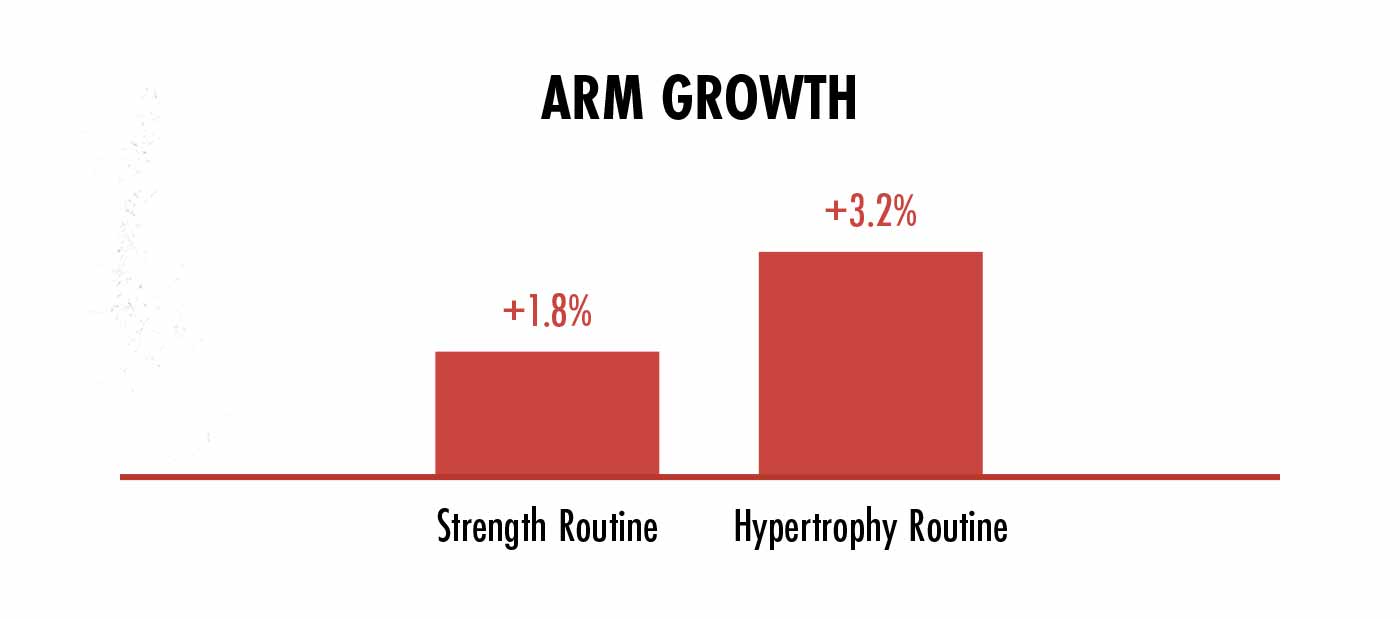

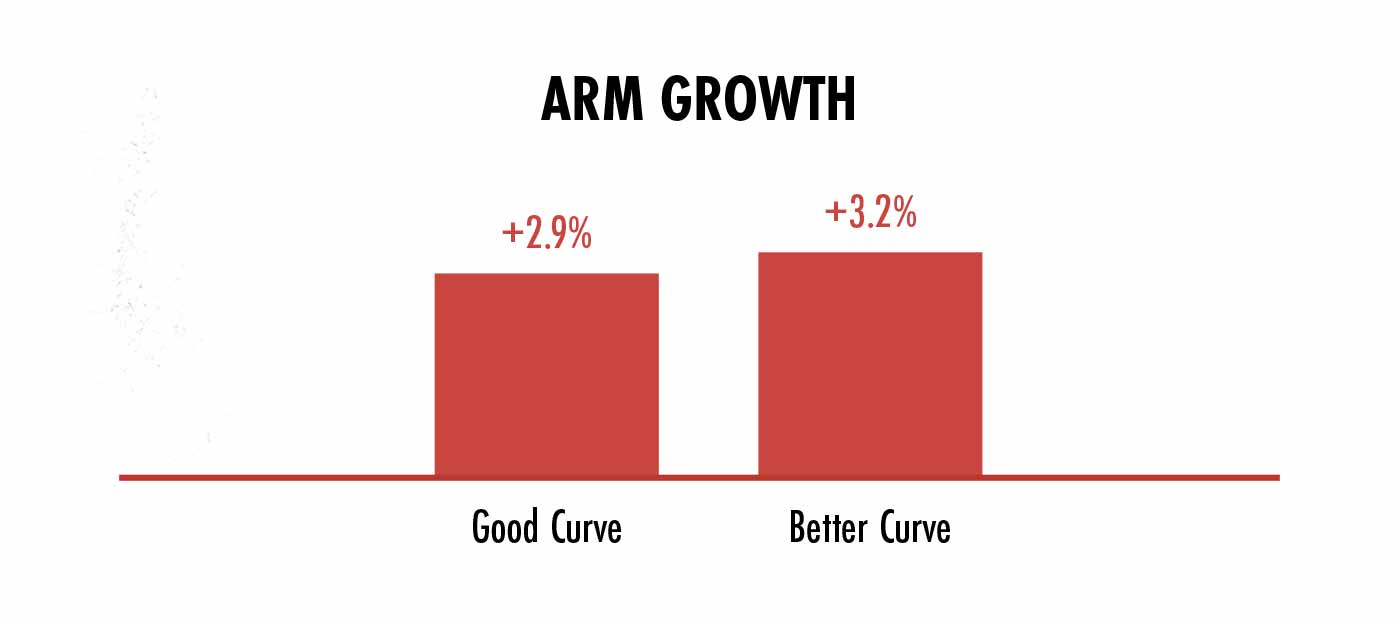

Last month, Staniszewski et al published a study that evaluated muscle hypertrophy with different training protocols and strength curves. They had one group doing a strength protocol, the other doing a hypertrophy protocol. Not surprisingly, the group doing hypertrophy training gained quite a bit more muscle than the group doing strength training.

The researchers were also looking at how strength curves affected biceps growth, though. They had each hypertrophy group doing four sets of preacher curls to failure with their 10-rep max and three minutes of rest between sets. Some used a preacher curl machine designed to perfectly align with their strength curves, and others used a standard curl machine with a flat resistance curve. After eight weeks, their arm growth was measured:

What we’re seeing here is that min-maxing the strength curve hardly had any impact at all. Yes, the better strength curve did result in slightly more growth, but the difference didn’t reach statistical significance, so even that small improvement could be merely due to chance.

However, both groups of participants were using preacher curl machines with fairly good strength curves. For instance, both loaded the biceps in a stretched position with a challenging weight. One machine had a slightly better strength curve and the participants saw slightly better growth. This shows that small differences in strength curves don’t matter very much. If we can make the range of motion more challenging throughout, maybe we can eke out slightly more muscle growth.

But if we compare exercises with dramatically different strength curves, do we see dramatically different amounts of muscle growth? Yes, we do. Let’s talk about why that is.

This is all to say that understanding strength curves can help us min-max our exercise selection, blast through plateaus, bring up lagging muscles, and build more muscle. But we need to be careful that we aren’t improving the strength curve of one specific muscle at the expense of everything else.

The Importance of Challenging Our Muscles At Long Muscle Lengths

When we’re talking about strength curves, we’re talking about how different lifts can be challenging at different parts of the range of motion. In the above section, we explained how when strength curves are similar, muscle growth is similar. But what happens if we compare two totally different strength curves?

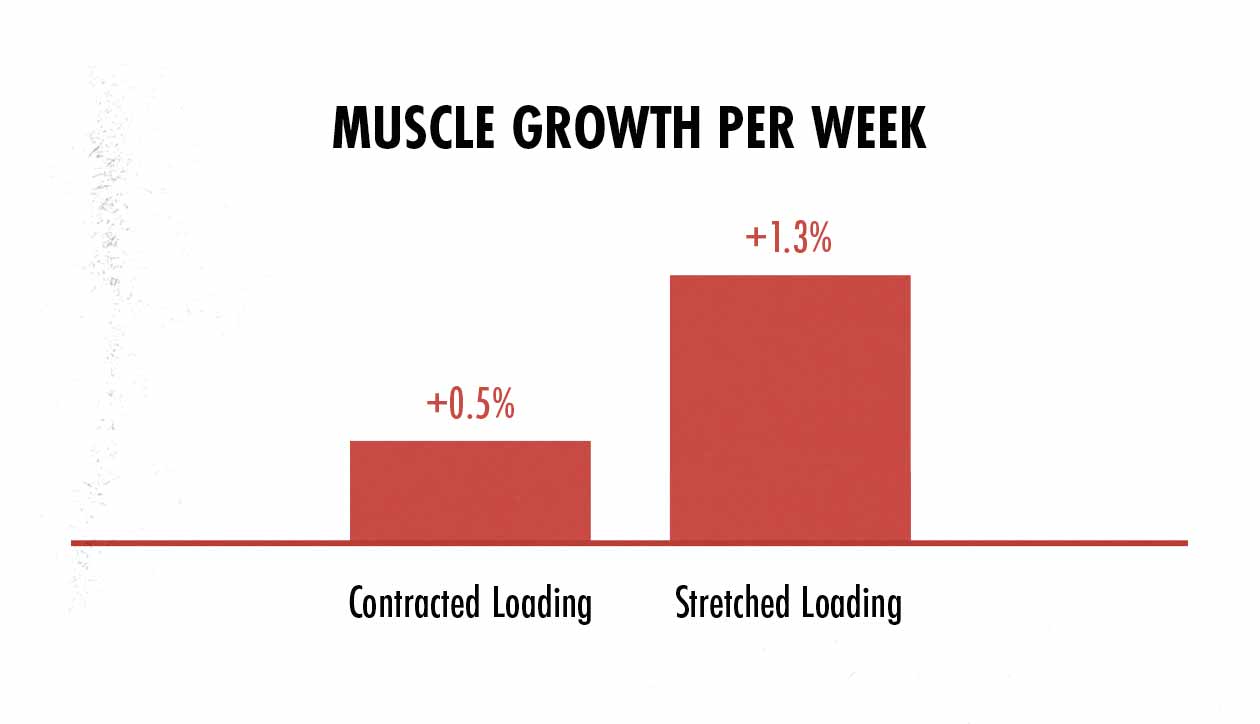

Let’s imagine one lift that’s only challenging at the very bottom, when our muscles are stretched out under a heavy load, and compare it against a lift that’s only challenging near the top, when our muscles are in a contracted position. Which lift will stimulate more muscle growth?

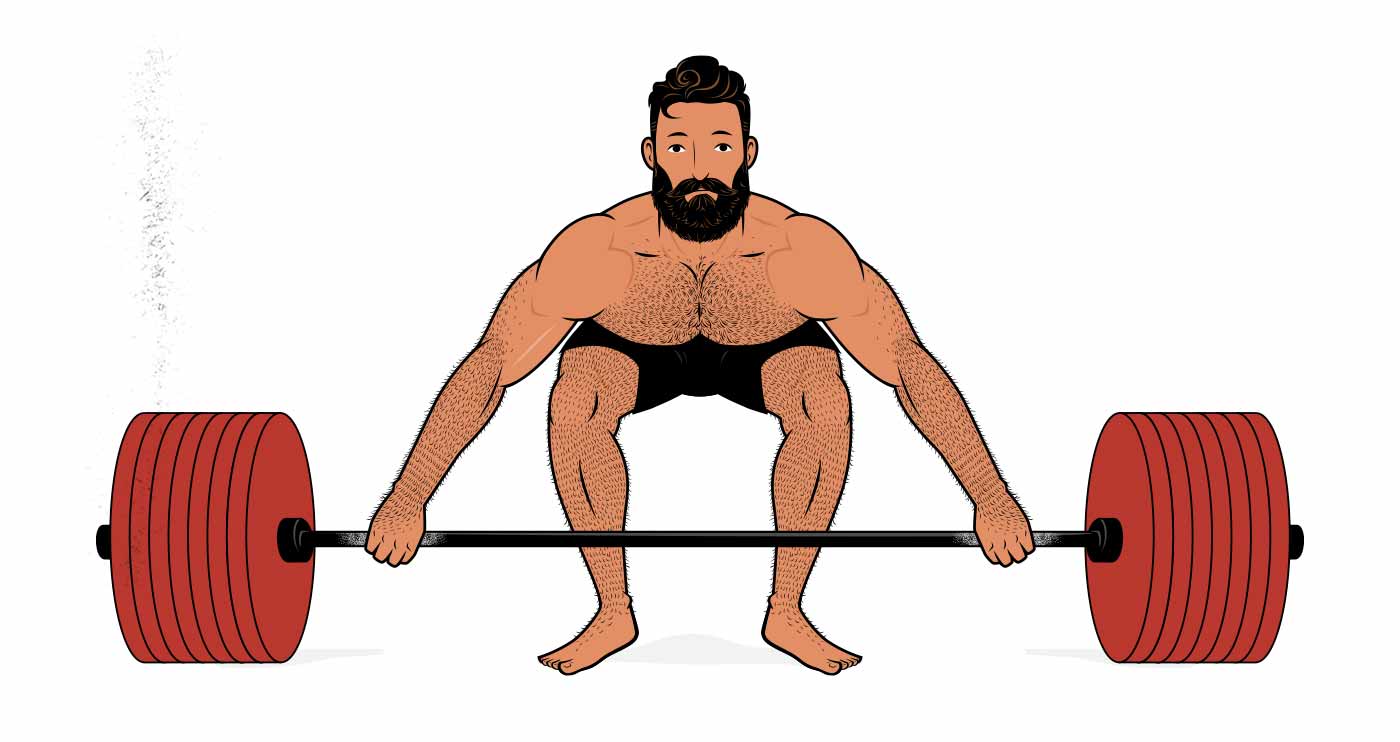

For example, let’s imagine loading up a barbell with a thousand pounds and setting up for a snatch-grip deadlift. What’s special about the snatch-grip deadlift is that the wider we grip the bar, the deeper we need to bend, allowing us to adjust our grip width so that we have a maximal stretch on our hamstrings while still maintaining a neutral spine. But in this example, we’ve loaded the barbell with a thousand pounds, and so the barbell isn’t going to move. We’re maximally challenging our muscles in a stretched position and that’s it.

Now let’s imagine setting that same thousand-pound barbell up, but this time we’re setting it up on safety bars above our knees—an above-the-knee rack pull. We still can’t lift it, so our hamstrings are still being maximally challenged, it’s just that now they’re being challenged at a much shorter muscle length.

Which lift will stimulate more muscle growth?

Over the years, a number of studies have tried to answer that question. If we look at a meta-analysis that pooled all of the research, we see that challenging our muscles in a stretched position stimulated nearly three times as much muscle growth as challenging our muscles in a contracted position. So we’d expect the guy doing snatch-grip deadlifts to build nearly three times as much muscle as the guy doing above-the-knee rack pulls. Crazy, right?

What’s happening here is that our muscles are kind of like elastics. When our muscles are stretched, there’s tension pulling them back to their resting lengths. This “passive” tension adds extra tension to the lift, increasing the mechanical tension on our muscles, and thus increasing muscle hypertrophy. When our muscles are contracted, yes, muscle activation is super high, and, yes, EMG ratings explode off the charts, but because there’s less overall mechanical tension, there’s much less muscle growth.

Now, this is obviously an extreme example. Most people don’t lift zero range of motion. But we see this same principle holding true even when using a full range of motion. For example, there’s also a study showing that squats, which are hard at the bottom, produce twice as much muscle growth as hip thrusts, which are hard at the top.

This research also lines up with conventional wisdom and training methods. Most people know that they should squat, deadlift, and bench press fairly deep when trying to build muscle. And all three of those lifts challenge our muscles the most when they’re at longer lengths. They all take advantage of this principle. No wonder they’re so famous.

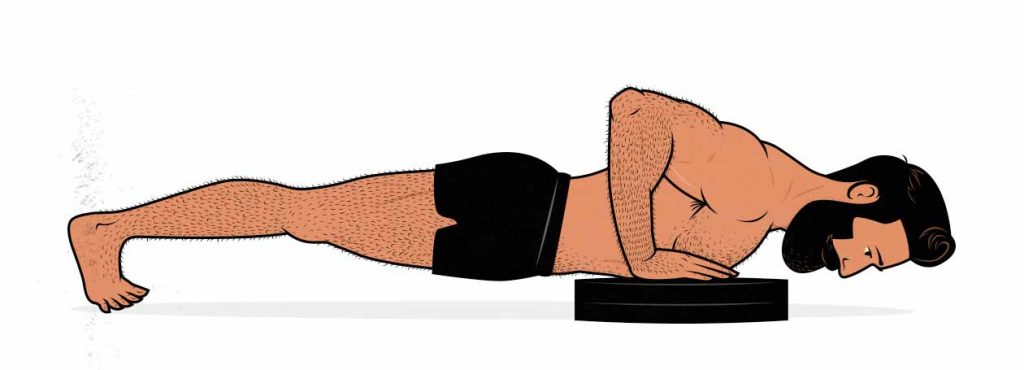

Still, this is a useful piece of information to keep in mind when choosing lifts. This is why it might not be the best idea to build a routine around partial squats, above-the-knee rack pulls, and bench presses with a huge arch. By limiting the amount of stretch we get on our muscles, we limit the amount of muscle growth we stimulate. We may also want to switch low-bar back squats for front squats to get a better stretch on our quads, switch push-ups to deficit push-ups to get a better stretch on our chests, and switch triceps push-downs to overhead extensions to get a better stretch on our triceps.

More controversially, this is also why training with just resistance bands isn’t great for building muscle. The lifts are too easy when our muscles are in a stretched position, too hard when our muscles are in a contracted position. It’s the worst possible strength curve for building muscle. But there’s some nuance to it, especially if we combine light resistance bands with heavy free weights. More on that below.

The Best Strength Curves for Building Muscle

It’s true that a flatter strength curve can be better for building muscle. After all, the flatter the strength curve is, the more challenging the entire range of motion will be. However, not all parts of the range of motion stimulate equal amounts of muscle growth, and so there are two more factors to consider:

- If the lift is hardest where our muscles are strongest, we’ll be able to lift more weight through the entire range of motion, stimulating more muscle growth. For example, the barbell curl is a nice lift because it allows us to lift quite a lot of weight with our biceps.

- If the lift is hard when our muscles are in a stretched position, it will stimulate more muscle growth. For example, the preacher curl is a nice lift because it loads our biceps up heavy when they’re in a stretched position.

These two points change how we evaluate strength curves. We’re no longer looking for lifts that have a flat strength curve, we’re looking for lifts that stretch our muscles at the bottom, are challenging at the bottom, and that allow us to lift a good amount of weight overall.

For example, if we look at the front squat, we see that our quads are worked through a large range of motion, they get a nice stretch at the bottom, the bottom part of the lift is challenging, and the sticking point occurs at the midway point, which is where our quads are the strongest. This makes the front squat a great exercise for our quads—perhaps even the best exercise for our quads.

Now, some might argue that after getting past the sticking point of the squat, the lockout becomes trivially easy, and that’s true. However, that final part of the range of motion isn’t very good for stimulating muscle growth anyway, so adding accomodating resistance (bands or chains) to make the lockout harder wouldn’t necessarily yield more muscle growth. It might, but it’s not likely to make a huge difference.

That brings up another point, too. If we do heavy partials, such as half squats or quarter squats, where we never hit full depth, yes, we’d be able to lift much more weight, but we’d be doing it through the wrong part of the range of motion. We’d be skipping the more effective parts of the lift: the stretch and the sticking point. That might explain why partials stimulate less muscle growth than using a full range of motion.

So when choosing lifts, we can ask ourselves questions like these:

- Does the range of motion give our target muscles a good stretch in the bottom position? If yes, great.

- Is the lift challenging while our muscles are stretched? If yes, great.

- Is our sticking point somewhere in the middle of the lift? If yes, great.

- Is the lockout portion of the lift easy? If yes, it doesn’t really matter. We might just want to skip the lockout to keep more constant tension on our muscles.

Strength Curve Examples

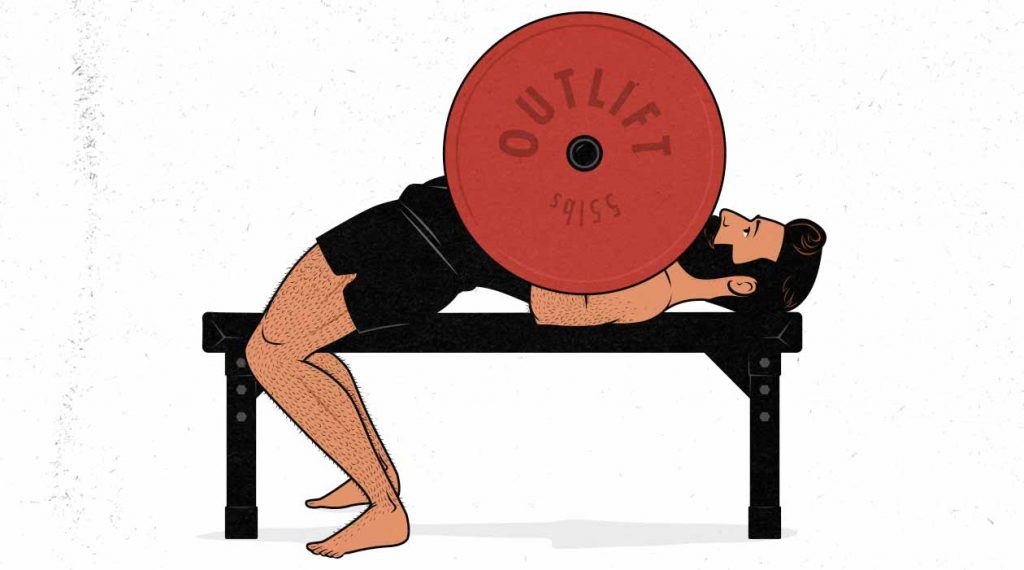

Bench Press Strength Curve

If we look at the bench press, where we stretch our chests out at the bottom of the lift, where most of the range of motion is fairly challenging, and where we can keep constant tension on our chests throughout the entire set (by avoiding a full lockout), then we see why it’s so good for building a bigger chest. The same is true with deficit push-ups and dumbbell flyes. They’re hardest when our chests are in a stretched position.

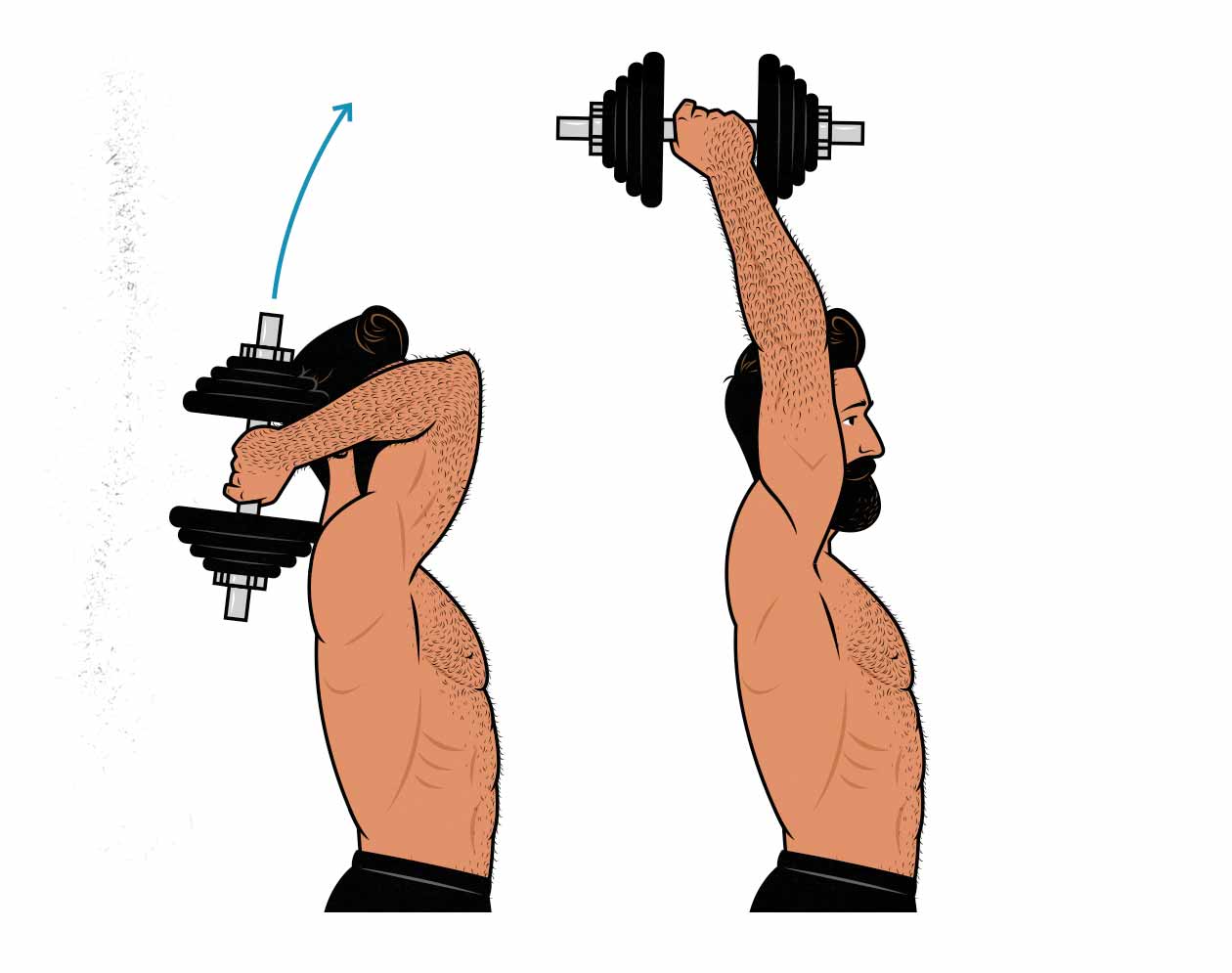

However, because our triceps aren’t maximally challenged at the sticking point, aren’t lifting from a heavy stretch, and aren’t under constant tension, these pushing movements aren’t good for building bigger triceps. This is one reason why both compound and isolation lifts are important when putting together a hypertrophy routine. A much better lift for our triceps is the triceps extension, which works out triceps through a larger range of motion, challenges them in a stretched position, and has a flatter strength curve (especially if we avoid locking them out).

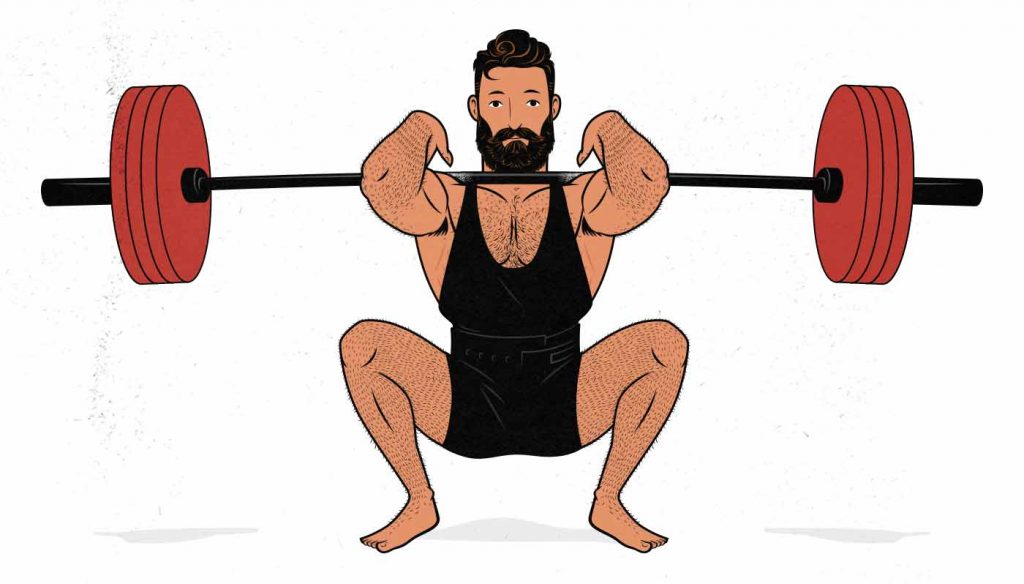

Squat Strength Curve

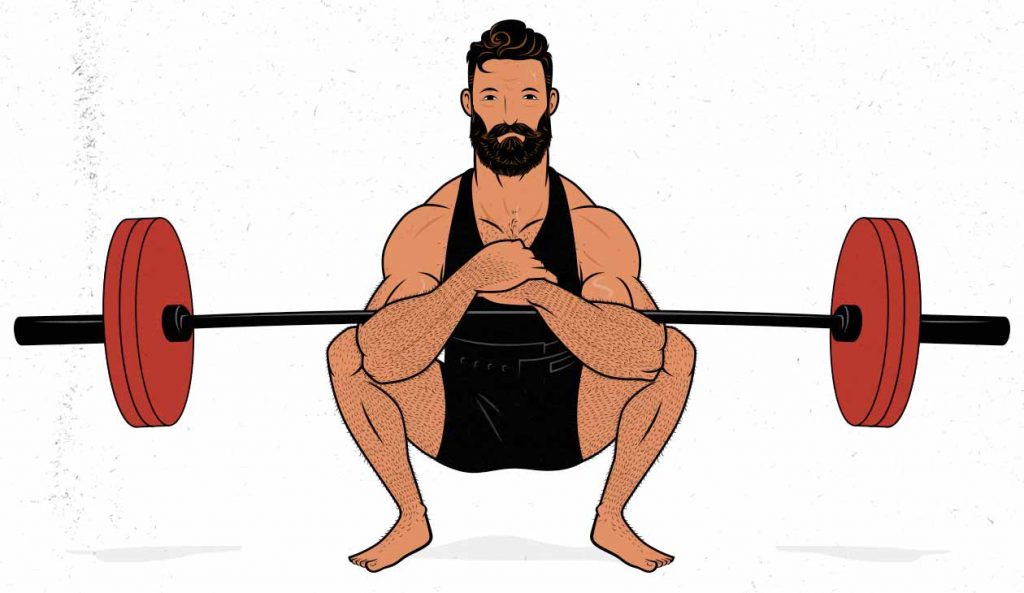

Different squat variations have different strength curves. Powerlifters will often use a low-bar position, a wide stance, and squat to parallel depth, like so:

This creates a linear strength curve, where the lift is hardest at the very bottom. What’s interesting is that most people squat as a way to bulk up their quads, but this shortens the range of motion on the quads while increasing the range of motion on the glutes. It makes the squat more hip-dominant, more similar to a deadlift or good morning.

With the front squat, though, the torso is more upright, the stance is narrower, and the depth is deeper, like so:

With the front squat, there’s more of a stretch on the quads, less of a stretch on the glutes. It’s still fairly hard in the bottom position, but the sticking point is just above parallel, giving it a bell-shaped strength curve. Yes, the top part of the lift is fairly easy, and we could improve that with chains or resistance bands, but the bottom part is more important, and the bottom part is solid, especially if we start lifting with our full strength right from the beginning.

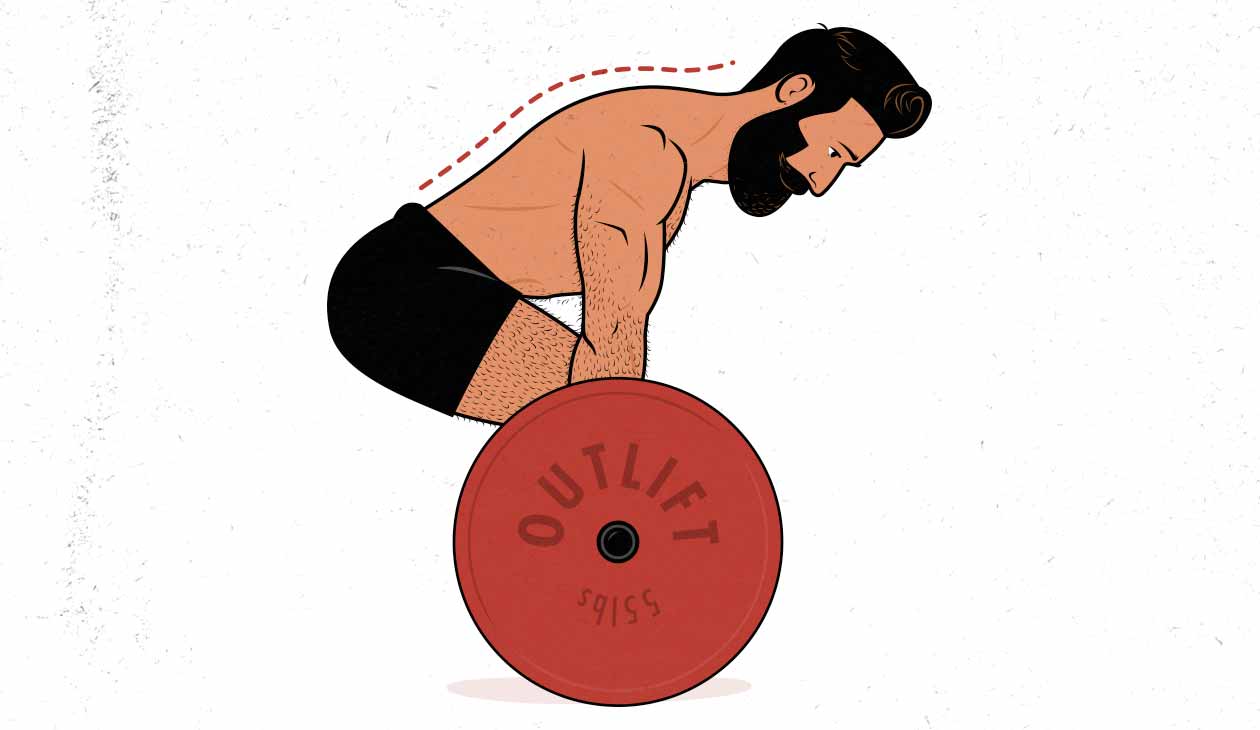

Deadlift Strength Curve

The sumo deadlift tends to start with our hips fairly far back, creating a long moment arm, and so the hardest part of the lift is breaking the barbell off the floor (linear strength curve). With the conventional deadlift, our starting position is a bit more compact, and so the hardest part of the lift tends to be a few inches off the floor (a bell-shaped strength curve). Even so, the strength curves are fairly similar. In either case, we get a nice stretch on our hamstrings and glutes at the bottom of the lift, the load is heavy in that stretched position, and the lift only starts to get easier at the lockout.

It’s fairly common to add bands and chains to deadlifts, making the lift a bit easier at the beginning, a bit harder at the top. This flattens the strength curve, makes the lift more metabolically taxing, and might slightly improve hypertrophy. However, since the bottom part of the lift is more important for building muscle, and the bottom part is nicely loaded, even regular deadlifts are fairly ideal for building muscle.

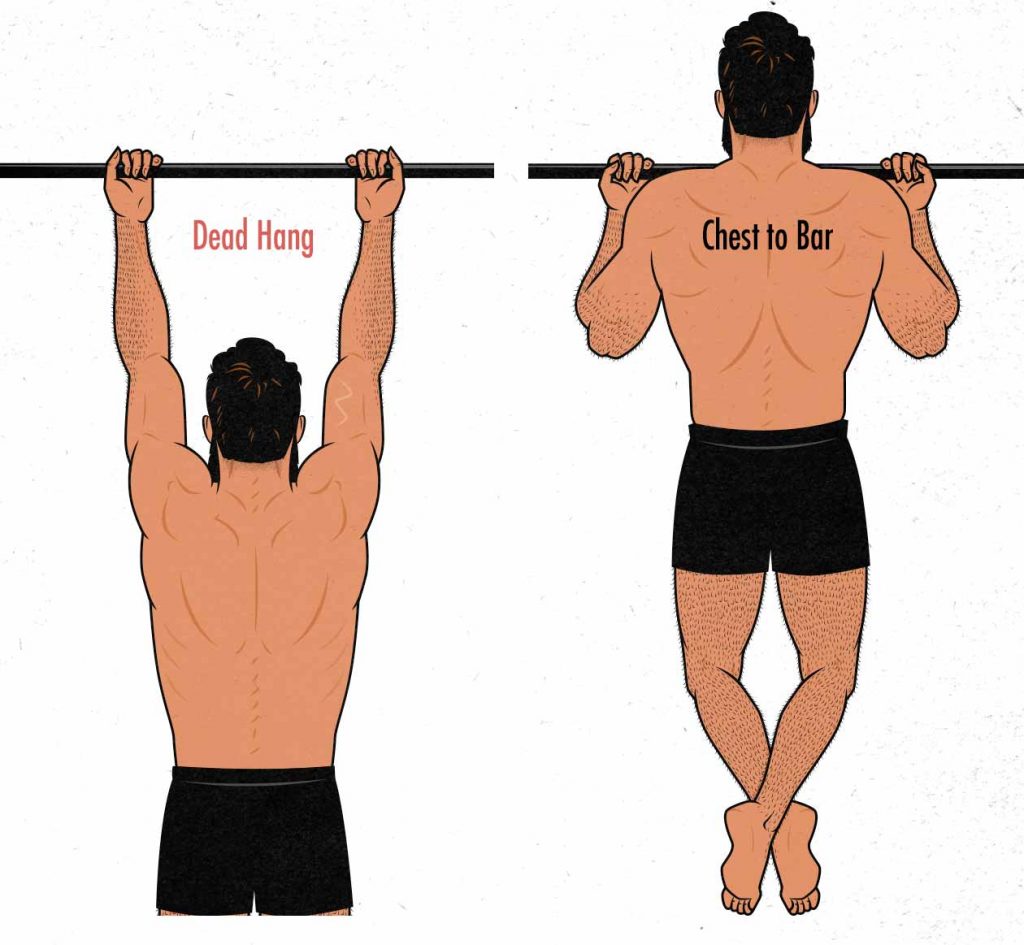

Chin-Up Strength Curve

With the chin-up, things get trickier. The lift is easier at the bottom, when our lats and biceps are stretched, and it only gets hard as our chests get near the bar. That’s the opposite of what we want, but since so many back lifts share this problem, it’s not as simple as just choosing a better lift. The chin-up is the best back lift.

Fortunately, our lats are under a nice stretch at the bottom of the chin-up, we just need to challenge them there. One way to do that is to lift explosively right from the get-go, gathering momentum for that final part of the range of motion. This makes the chin-up a bit harder at the beginning, a bit easier at the top. It flattens the strength curve.

Another trick is to eke out a couple of partial reps even after we fail to bring our chests all the way to the bar. During these partial reps, our lats will bear more of the burden, and so get a better hypertrophy stimulus.

I think chin-ups are a lift that benefits from some accessory work, though.

- For our lats, one option is to choose lifts that are hardest when our lats are in their strongest position, such as the straight-arm pulldown. Perhaps a better option is to choose lifts that are hardest when our lats are stretched, such as the pullover.

- For our biceps, one option is to choose the barbell curl, which is hardest when our biceps are in a fairly strong position. Another option is to choose the incline curl or preacher curl, which are hardest when our biceps are in a stretched position.

Overhead Press Strength Curve

With the overhead press, the lift only starts to get hard once the barbell gets to around forehead height. And once it gets to forehead height, it can get really hard. It’s common to get stuck with the barbell just above our foreheads, slowly grinding the barbell higher. Like the front squat, bench press, and conventional deadlift, this creates a bell-shaped strength curve. But with the overhead press, the curve is so extreme that only a small part of the range of motion is challenging enough to produce a robust amount of muscle growth.

As with the chin-up, the trick is to lift explosively, heaving the barbell off our chests. Some people even take this so far as to do a sort of push press, giving the barbell momentum with a bit of leg drive. Exploding the barbell up makes the lift harder at the beginning and easier at the sticking point, improving the strength curve.

Because the overhead press doesn’t challenge our front delts in a stretched position, it might help to include some moderate-grip bench press or deficit push-ups, which are hardest when our shoulders are stretched.

But this is a good time to point out that not every lift needs a great strength curve. It helps to build our routines out of lifts that are challenging through a large range of motion, but not every lift in our routines needs to meet those high standards. Lateral raises don’t have a great strength curve, but when combined with overhead pressing, they can certainly help us boost our training volume higher, giving us far more shoulder growth.

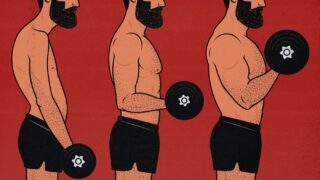

Biceps Curl Strength Curve

If we look at biceps curls with a barbell or curl-bar. Our biceps are strongest in the middle of the range of motion, which is where the biceps curl is the hardest. Great. However, there’s no loading of our biceps in a stretched position, which is where a lot of muscle growth is stimulated.

Barbell curls may still be the best (isolation) lift for building bigger biceps, but including variations like the preacher curl or incline curl may also help. That way we have the barbell curl to challenge our biceps where they’re strongest and the preacher curl to challenge our biceps while they’re stretched. Neither lift is perfect, but by combining both, we get the best of both worlds.

Barbell Row Strength Curve

The barbell row has perhaps the most severe strength curve problem of all popular lifts. Our lats are weak to the point of being useless at the top of the range of motion, which also happens to be the hardest part of the lift. This makes it so hard to bring the barbell all the way to our torsos that we’re forced to use fairly light weights. We can improve that somewhat by driving the barbell up with our hips (a “power row”), but even so, only a very small portion of the lift will be challenging enough on our upper-back muscles to produce much muscle growth. Plus, the bottom of the barbell row, our lats aren’t in a stretched position, let alone challenged there.

On the bright side, there are other muscles in our backs that are worked quite well by the barbell row. It may not be ideal for our lats, but it winds up being pretty good for our spinal erectors, rhomboids, rear delts, and mid/lower traps. It’s also good for our hips, hamstrings, and forearms (brachioradialis). Because it’s so good for our posterior chain and forearms, it makes a great accessory lift for the deadlift (which is why it’s so popular with powerlifters).

If you’re trying to choose a horizontal row variation that’s better for bulking up your upper-back muscles, the t-bar row machine has a much better strength curve. How much does that matter? Maybe not so much. But if you have access to it, it’s a great upper-back lift.

Glute Bridge/Hip Thrust Strength Curve

Some lifts don’t have the best strength curve. If we look at the glute bridge and hip thrust, for example. The hardest part of the lift is the lockout, when our glutes are in a shortened position. That might be why squats produce so much more glute growth. They work our glutes harder in a stretched position. This is one reason why squats (and deadlifts) are often thought of as main lifts, whereas glute bridges and hip thrusts are usually considered accessory lifts.

Do Exercise Machines Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

As we’ve covered above, with free weight exercises, the resistance curve changes as we lift through the range of motion. This almost always makes the lift harder in the middle, when our levers are horizontal. For example, the barbell curl is hardest when our forearms are horizontal:

One advantage of using exercise machines is that they’ll often provide us with stable moment arms. If we imagine a curl machine, where the weight is rotating around an axle, then the moment arm is constant throughout the entire range of motion, providing our muscles with consistent tension:

However, our biceps have better leverage at moderate joint angles, and they’re strongest in a stretched position. So when we apply our bell-shaped strength curve to this flat resistance curve, the beginning and middle of the lift become too easy and the top becomes too hard. Most people fail at the very top of the lift. That’s not all that great for muscle growth. Barbell curls are better, given that we fail where our biceps are strongest. And preacher curls may be better still, given that the sticking point is when our biceps are somewhat stretched:

Exercise machines have other disadvantages as well. For starters, they aren’t as good at training our stabilizer muscles, and so they aren’t as good for stimulating overall muscle growth.

But each machine is a little different, and some do a pretty good job of lining up the resistance curve with our strength curve. For example, the t-bar row machine does a good job of fixing the strength curve problems with the barbell row. It takes our spinal erectors out of the lift, but it does a better job of bulking up our upper-back muscles.

Do Cable Machines Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

Bodybuilders often use cable machines to put more constant tension on their muscles throughout the lift. For example, with a cable fly, the hardest part of the lift is when our chests are in a fully contracted position. This is the same problem that we run into with the curl machine. We’re making the end of the lift harder at the cost of making the other parts of the lift easier. Better to do the opposite. We’ll build more muscle by loading up our chests heavy at the bottom of a bench press, deficit push-up, or dumbbell fly.

That’s not to say that all cable exercises are bad. But the goal isn’t merely to flatten the resistance curve, we also want to make sure that the overall strength curve is good for building muscle.

Do Resistance Bands Have Better Resistance Curves for Hypertrophy?

Our muscles grow best when we challenge them in a stretched position, so the best lifts for building muscle are the ones that are harder at the beginning and easier at the end. This is why the squat, bench press, and deadlift have better strength curves than the chin-up and barbell row.

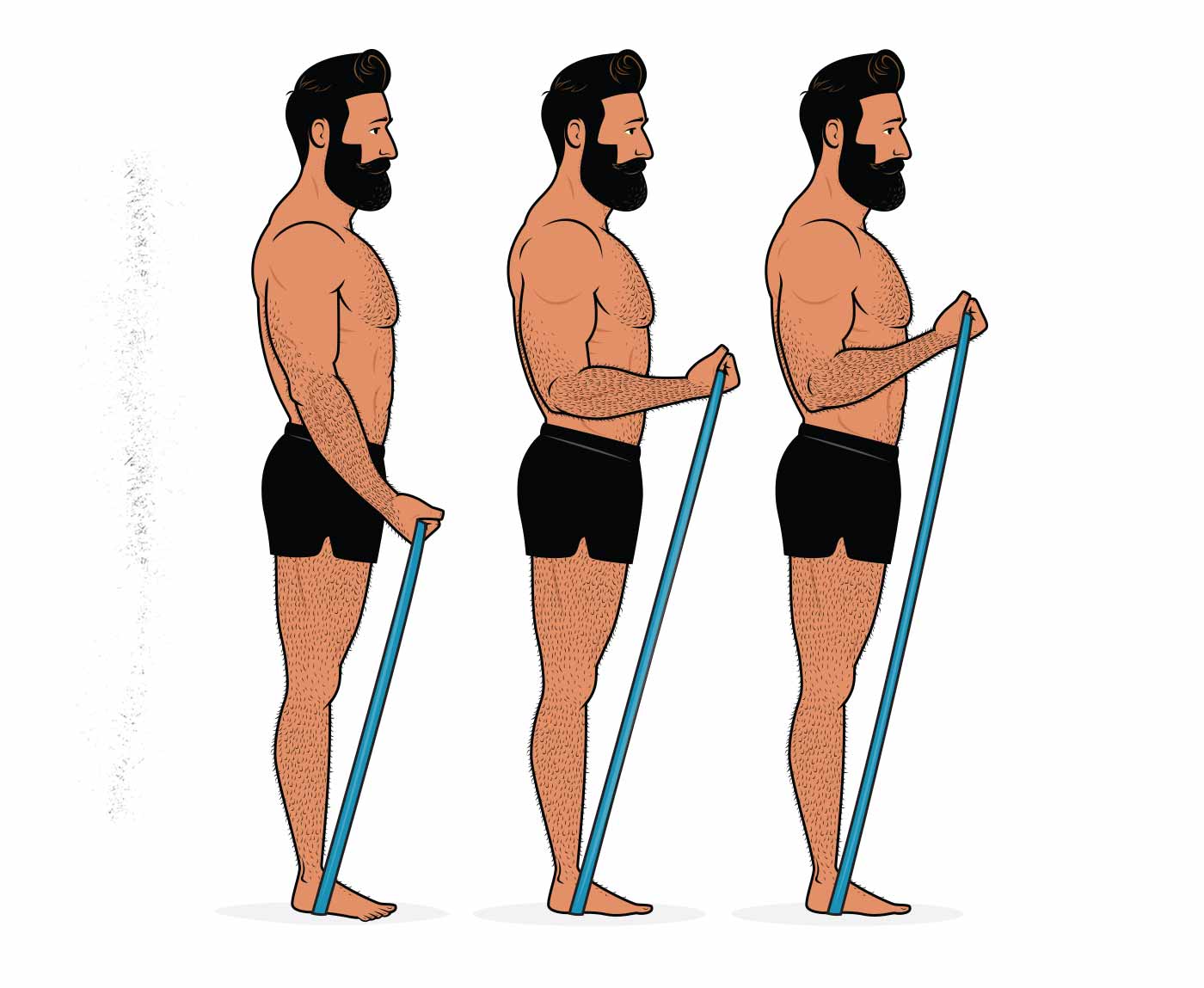

Resistance bands have a unique type of resistance curve called variable resistance. As the resistance band is stretched further, it offers gradually more resistance. This makes the beginning of the range of motion easier than the end. And so resistance bands make the strength curve of our lifts worse for building muscle.

Now, resistance bands are cheap and portable, so they can certainly be handy for building muscle in a pinch. Any set that’s brought close enough to failure can stimulate muscle growth, so it’s certainly possible to build an impressive physique with resistance bands. But their resistance curves are not very good for gaining size of strength. Dumbbells, barbells, exercise machines, and cables are all quite a bit better. (If that sounds controversial or unclear, we have an in-depth article on resistance bands.)

Does Accommodating Resistance Increase Hypertrophy?

Okay, so we’ve covered why the variable resistance offered by resistance bands isn’t good for building muscle. It makes the beginning of the lift too easy, the end too hard. Accommodating resistance is similar in the sense that it makes the end of a lift harder, but the overall effect is actually quite different.

With accommodating resistance, most of the weight can come from free weights. And with a lot of free-weight lifts, the beginning is quite a bit harder than the end. If we make the end of the lift a bit harder by adding bands, that helps to flatten the strength curve, and in this case, that can be a good thing.

For example, most of us fail our squats when our thighs are horizontal. If we can clear that point, the rest of the lift becomes easy—so easy that it stops stimulating muscle growth. So to make a lift more challenging throughout the entire range of motion, one trick is to use accommodating resistance, such as bands or chains. If we toss some chains around the barbell or fasten it to the ground with a resistance band, then the further we lift the barbell, the heavier it becomes. That allows us to stimulate muscle growth all throughout the range of motion.

For another example, consider the bench press. The longest moment arms are when our upper arms are parallel with the ground, which is also when our pecs are at their resting length. So the resistance curve lines up beautifully with the strength curve for our pecs. We might still fail at that point, of course, but even then, the entire range of motion still tends to be challenging enough to provoke a good amount of muscle growth. If we consider our triceps, though, then we see something different. Most of us are limited by our chest strength on the bench press, not our triceps strength. The lockout portion of the lift is too easy to stimulate much triceps growth. We could, therefore, make the bench press better at stimulating triceps growth by making the lockout portion of the lift heavier, which we can do by adding bands or chains.

Another potential to accommodating resistance is that we get to hold more weight. For example, if we’re deadlifting with chains, by the time we’re standing up with the barbell, we might be holding an extra hundred pounds in our hands, helping us to build harder bones and tougher tendons, and potentially increasing our potential for muscle growth. There’s not a lot of research looking into this, but it’s plausible that increasing our bone mass allows our frames to hold more muscle mass.

So, at least in theory, accommodating resistance should have a neutral or positive effect on muscle growth, but it’s hard to say with any certainty, and the benefit would likely be fairly small. As of now, there isn’t much research looking into accommodating resistance for hypertrophy training, and the limited research that we do have shows no effect (study). Mind you, this could merely be a type two error (where the benefit is real, it’s just not big enough to reach statistical significance).

A word of caution, though, is to make sure that you know what you’re doing. Most lifts are easier at the top—squats, bench press, deadlifts, curls, and so on—but there are exceptions. Using a resistance band for a chin-up or barbell row, for example, would be a mistake. After all, these pulling movements are already easiest at the bottom and hardest at the top. If we make the bottom even easier and the top even harder, we’re making the strength curve much worse.

Another common mistake is to make the accommodating resistance too extreme, which can create an exaggerated sticking point at another part of the lift. That wouldn’t necessarily make the lift better, and it might even make it worse. Better to keep the sticking point the same, just to make it less exaggerated. With the bench press, for example, the harder you can get the lockout while still failing at your usual sticking point, the more you’ll improve triceps growth without reducing chest growth.

Key Takeaways

Most of the big barbell lifts have fairly good strength curves by default. Our bodies have good leverage for picking up free weights, allowing us to lift a lot of weight through a large range of motion and challenge our muscles where they’re strongest.

In some cases, trying to overoptimize strength curves actually makes a lift worse. For example, the bench press and dumbbell fly already have great strength curves for building muscle in our chests. If we start focusing on cable flyes instead, yes, our chests will need to work harder in a contracted position, but that barely matters for building muscle anyway, and we lose the benefits of challenging our chests in a stretched position.

In other cases, choosing slightly weirder variations might yield more muscle growth. For example, the preacher curl and incline curl both load our biceps in a stretched position, and that may very well help to stimulate more biceps growth.

Furthermore, there are some lifts with a more extreme curve where using momentum can help us get through the sticking point. The overhead press, barbell row, barbell curl, and chin-up are all examples of lifts where it can help to lift more explosively.

Alright, now you know everything. But if you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. We also have our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program and Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program for beginners. If you liked this article, I think you’d love our full programs.

The study that you link to support the claim “When our muscles are challenged in a stretched position, we get more muscle growth” doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the claim; it’s a meta-analysis of studies on partial vs full range of motion as it impacts hypertrophy. Some of the studies included are looking at partial ranges of motion at the “middle” of the ROM rather than at either end, so they’re certainly irrelevant, and even just considering the studies that look at partial ROM at an end (and it’s not clear to me whether they necessarily mean the “beginning” or the “end” of the ROM), I don’t think it’s justifiable to conclude that it’s the muscle length, specifically, that matters; you would want to look at studies that compare a partial ROM at the start of the motion with a similar partial ROM at the end of the motion.

The authors of that meta-analysis only had this to say on the subject of muscle lengths:

> A recent systematic review concluded that isometric training at longer muscle lengths elicited greater increases in muscle size compared with isometric training at shorter lengths.10 The authors reported average increases in muscle size of 1.16% per week when training with joint angles>70° compared with just 0.47% per week with angles⩽70° (effect size difference=0.35). This finding seems to suggest that training with a partial ROM may be equally effective as a full ROM provided that the partial excursion is carried out at a long muscle length. *However, it is important to note that results are specific to isometric training at a fixed joint angle. Although such protocols are insightful for generating mechanistic hypotheses, their designs are of questionable relevance to ecologically valid RT programs, thereby limiting the ability to draw practical inferences from the findings.*

Hey James, thank you for the thoughtful comment. What you’re saying makes sense, and I largely agree with you. If all we had was this meta-analysis, it would be too soon to know with any degree of certainty whether challenging our muscles at longer muscle lengths was better for muscle growth. But this is just one of several papers.

I think the study you’re looking for is this Pedrosa et al paper. The researchers had women doing leg extensions at different parts of the range of motion, with some training their quads at short muscle lengths, some at long muscle lengths, and others using a full range of motion. The group training their quads at long muscle lengths got over twice as much muscle growth as the group training their quads at short muscle lengths. What’s really neat, though, is the group training at long muscle lengths also got more muscle growth than the group using a full range of motion.

Here’s another study, this one by Maeo et al, showing greater hamstring growth when doing seated hamstring curls (longer muscle lengths) than when doing lying hamstring curls (shorter muscle lengths). Exact same range of motion and movement at the knee joint, just a different degree of hamstring stretch coming from the hips.

So we’ve got a growing number of studies looking at different lifts, different muscles, and using different methods. All of them are showing that training our muscles at longer muscle lengths stimulates more muscle growth. Obviously, it would be better if there was even more research, but I think the evidence is really starting to pile up here.

Hi Shane,I was wondering if a free weight T-bar row would have the same strength curve as the machine.

Hey David! Should be similar, yeah 🙂

Hi Shane. Curious if incline bench press at 45 degrees has same strength curve as flat bench? Since you mentioned overhead press was hardest in the middle

Hey Neil, good question. On the bench press, incline bench press, and overhead press, the lift is hardest when your upper arms are parallel to the ground, creating the longest moment arm. With the bench press, that’s usually right near the bottom, challenging your chest and shoulders in a deep strength. On the incline bench, it’s maybe 1/4 of the way through the lift, when your chest and shoulders are a little bit contracted. On the overhead press, it’s in the middle of the lift, when the shoulders are about halfway contracted.

That gives the bench press the best strength curve for building muscle. It challenges your chest and shoulders in the deepest stretch. That’s just one factor, though. It’s an important factor, but it’s still just one factor. The incline bench press and overhead press are still great lifts for working the fronts of your shoulders.

It’s really hard to beat a deep squat (like a front squat), the bench press, and the Romanian deadlift. They do such a good job of working your muscles in a deep stretch with heavy loads. But not all muscles are easy to train at long lengths, and plenty of other exercises are amazing for other reasons. Most people build big shoulders with lifts like the overhead press and incline bench press.

Thanks. I’m trying to grow the lower part of my front delts. I’ve been focusing too much on ohp. So incline will still get that stretch growth. Sarcomeres in parallel right? I’m thinking of doing push-ups too since I don’t have a spotter at the moment. What would you say about 15-30 incline

When you’re trying to build muscle, you can think about stimulating different sections of muscle fibres. So, for instance, with your shoulders, you’ve got your front delts, side delts, and rear delts. Those different bundles of muscle fibres are stimulated with different movements. With your chest, you’ve got the fibres that connect to your abdominal region (lower chest), your sternum (mid chest) and your collarbones (upper chest). Again, these are different groups of fibres you can stimulate with slightly different movements.

What you’re talking about is trying to grow the upper or lower part OF THE SAME MUSCLE FIBRE. The lower part of your front delt has the same muscle fibres as the upper part. With that said, there’s some evidence showing that stretch growth DOES do a better job of hypertrophying the distal regions of muscle fibres. So you’re not wrong. Trying to challenge your shoulders in a deeper stretch might help. It might also speed up growth overall.

Push-ups can be great for shoulder growth. So can a flat bench. Just use a narrower hand position and keep your elbows more tucked. That way you’re shifting emphasis away from your lower and mid chest over to your shoulders and upper chest. There’s also some research showing that the shoulders tend to contribute more to the bench press when the loads are heavier. So maybe think of doing 6–8 reps instead of 10–15 reps. Maybe.

The real trick is to see what works your shoulders, pumps them up, tires them out, and makes them sore the next day. Keep experimenting to see what your best lifts are. That includes experimenting with the incline angle. Everyone is a bit different.

Hey, bit late to the party but I’m looking for clarification on the resistance and strength curves for the pendulum squat compared the normal back squat. As I understand it: the resistance curve for a barbell back squat is flat, as the weight travels straight up and down, there are no external moment arms. The internal moment arms and the strength curve of the quads make the barbell back squat hard at the bottom but hardest in the middle, meaning the strength curve is bell shaped with a slight incline.

The pendulum squat has an arced bar path, meaning the external resistance curve is bell shaped. Meaning the torque exerted on the muscles is greatest in the middle of the movement (making the weight feel heavier in the middle). This when the quads are the strongest anyway, due to their natural strength curve, so, am I right in thinking that matching the strength and resistance curves makes the pendulum squat superior for hypertrophy?

Your thoughts on this would be greatly appreciated.

No worries! We haven’t turned the lights on yet.

The pendulum squat is often designed to be similarly challenging throughout the range of motion. It depends on the machine, though. Some machines let you adjust the resistance curve, too.

A barbell back squat is hardest when your thighs are parallel to the ground. If you try to accelerate the weight through the range of motion, exploding up out of the hole, then you’ll get full activation at the bottom, and the momentum will carry you through the sticking point. You’ll probably fail a little bit above parallel. That’s great.

It’s debatable whether lining up the strength curves and resistance curves (making the lift equally challenging throughout the range of motion) is better for gaining size and strength. Training at longer muscle lengths tends to stimulate more muscle growth. It could be that making the exercise harder at shorter muscle lengths creates fatigue in the part of the range of motion that stimulates less muscle growth, reducing the amount of energy you have to work at longer muscle lengths. If that’s the case, the barbell squat would be slightly better.

I don’t think anyone really knows which is optimal. I’m guessing they’re both fairly similar.