When Should You Lift to Failure?

Should we lift to failure when trying to gain muscle size? That’s a tricky question, and the answer depends on the situation. For example, experienced lifters are able to lift to failure more safely, but they stimulate more muscle growth by stopping just shy of failure, at least on compound lifts. Beginners, on the other hand, can build muscle faster by lifting to failure, but since they don’t have the skill to take compound lifts to failure safely, training to failure is best reserved for isolation lifts.

The situation grows murkier when we consider that it’s often better to leave reps in reserve when lifting in lower rep ranges, whereas lifting in higher rep ranges often demands that we push closer to failure.

Perhaps most importantly of all, it’s often hard to estimate exactly how many reps we’re leaving in reserve, and if we misjudge our efforts and fail to push ourselves hard enough, we may wind up failing to stimulate any muscle growth whatsoever.

In this article, we’ll cover the research looking into training to failure as it relates to gaining muscle size, discussing the nuances of when you should and shouldn’t leave reps in reserve.

What is Training to Failure?

The first thing we need to do is define failure. To some people, failure is when your training partner can no longer curl the weight you’re trying to bench press. To others, failure is when the set starts to feel too uncomfortable. Neither of those situations is failure.

There are a few good definitions of failure that you’ll commonly see, each with their own nuances to them:

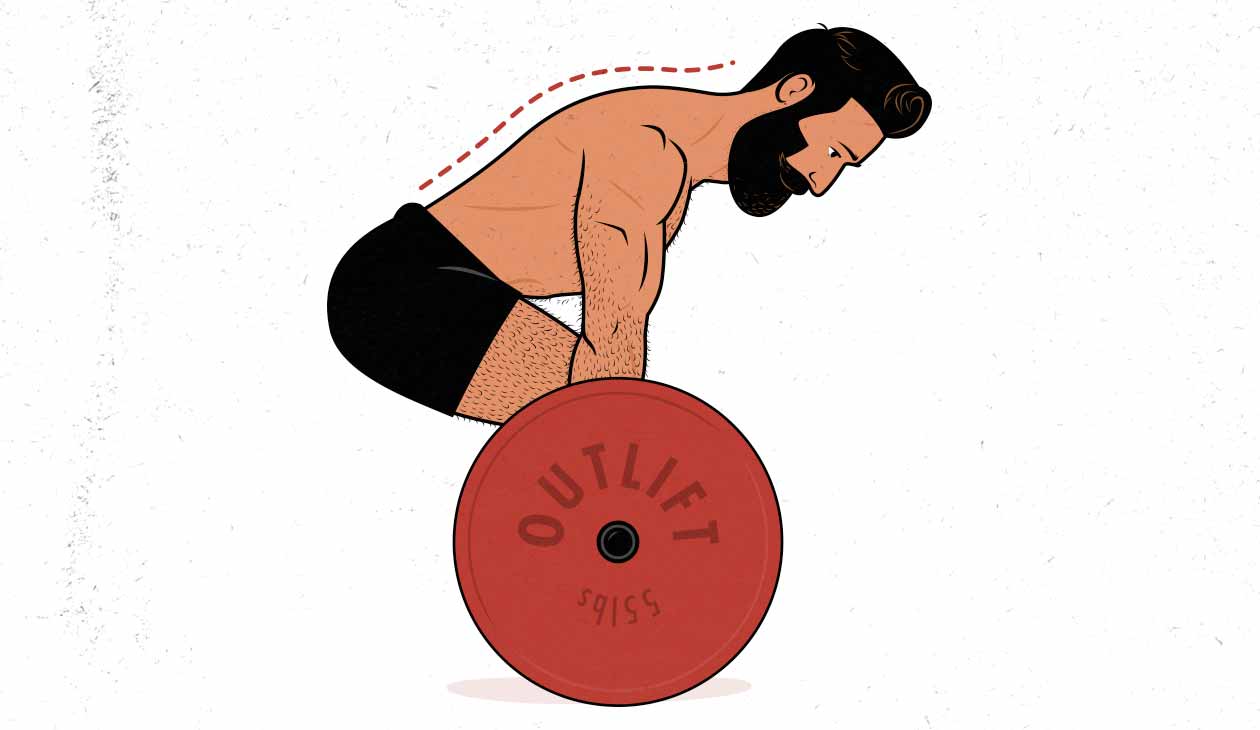

- Total failure: you cannot move the weight anymore, even with deviations in technique. The powerlifter who fails his deadlift with the bar a few inches off the floor—that’s total failure. This isn’t usually advisable during regular training sessions.

- Technical failure: you cannot move the weight anymore with proper technique. The bodybuilder who stops his set of deadlifts when he feels his lower back start to round is stopping at technical failure. This is how most people train to failure when trying to gain muscle size.

- 0 Reps in Reserve (0 RIR): you haven’t actually failed yet, but you know that you wouldn’t be able to do another complete repetition—you have no reps left in reserve, no reps in the tank. This is often better than technical failure for stimulating muscle growth, but it’s also more subjective—you have to guess how close to failure you are.

- 10 RPE: you haven’t necessarily failed, but your rating of perceived exertion (RPE) is at “max.” A 10 RPE usually corresponds with 0 reps in reserve, and so RPE and RIR are often (but not always) used interchangeably. We generally prefer using the reps in reserve system, since it’s a little easier to understand.

The distinctions here are small, but they can be meaningful. Someone stopping at technical failure might stop their set of deadlifts right before their lower back rounds, even if they could have done another couple of reps with a rounded back. This means less shear stress on the spine, a lower risk of injury, and they’ll feel less fatigued afterwards. But have they really gone to failure? Maybe not. It depends on how you define failure.

The next distinction happens when comparing 0 RIR with training to technical failure. Lifting to technical failure means grinding out as many reps as you possibly can, only stopping when you fail to complete a rep. The final rep, then, will have you actually failing at the sticking point. It’s objective: you lift until you fail, and so you learn exactly what you’re capable of.

If you were lifting to 0 RIR, though, you’d be stopping when you don’t think you can get another rep. There’s some guesswork involved. It’s subjective. In order to find out for sure how many reps you have left in the tank, you’d have to take the set all the way to technical failure. This makes it somewhat of a more advanced method. You already need a good understanding of what you’re capable of.

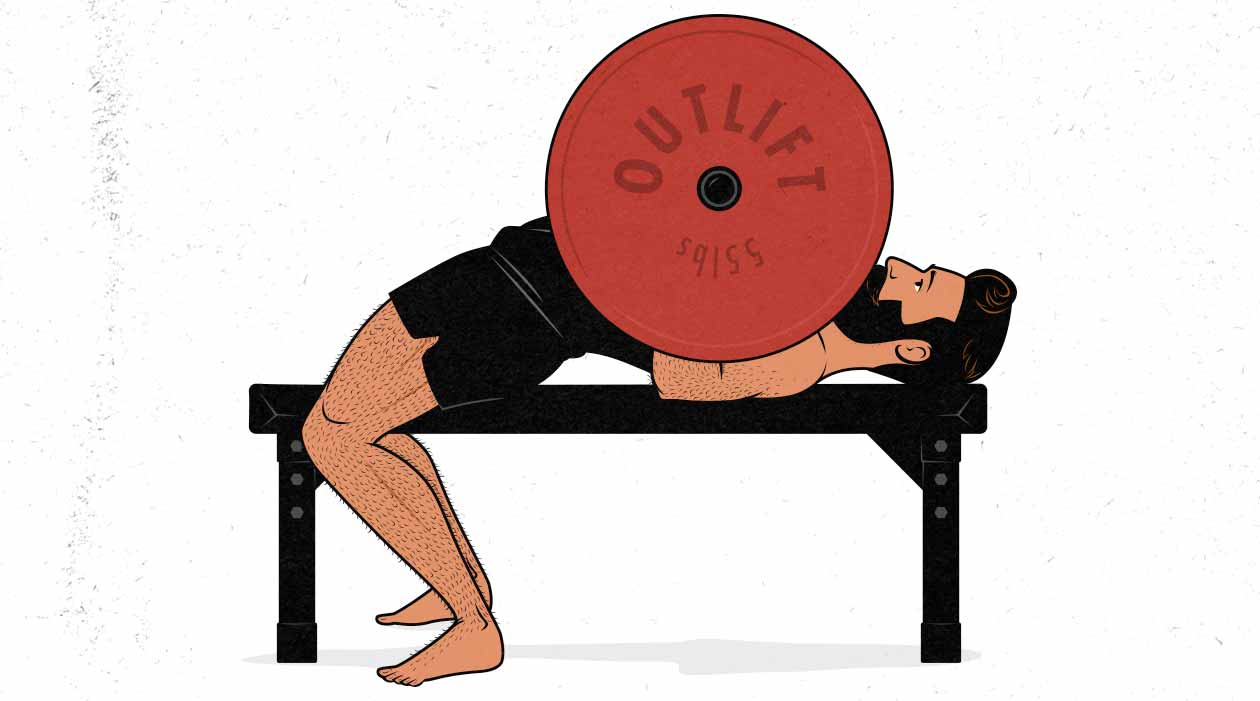

With bodybuilding and hypertrophy training, it’s usually recommended to stop at or before technical failure to reduce the risk of injury. For instance, it’s oft wise to avoid deadlifting with an excessively rounded lower back. On the other hand, with safer lifts, such as chin-ups and barbell curls, you’ll often see bodybuilders taking their lifts all the way to total failure, sometimes even cheating or swinging a little bit.

The next question is whether we should train all the way to technical failure or intentionally stop short. Both can be done safely, so now we’re considering how much muscle growth is stimulated, as well as how much muscle damage and fatigue it generates. There are a few popular approaches that you’ll find in bodybuilding and hypertrophy programs:

- No, we shouldn’t train to failure. That way we stimulate a comparable amount of muscle growth but with a lower risk of injury, burden ourselves with less fatigue, and recover faster.

- Yes, we should train to failure, but only on the final set of each exercise. That way we ration our energy from set to set, potentially allowing us to get more total reps—a higher training volume—but we still get any potential benefits of training to failure on the final set.

- Yes, we should train to failure, but only on our isolation lifts. That way we aren’t accruing fatigue or risking injury on the bigger compound lifts, but we still get to bring our muscles close to failure on our isolation lifts, which are often safer and easier to recover from.

- Yes, we should train to failure. That way we’re always training hard, always know exactly how strong we are, and are always pushing our muscles outside of their comfort zones. It makes our progress easier to measure, and there’s less risk of running into muscle growth plateaus due to lack of sufficient effort. With that said, it doesn’t necessarily stimulate more muscle growth, and it’s quite a bit more fatiguing.

All four of these approaches can make sense, depending on your goals and what kind of training you’re doing. The two approaches in the middle might sound like they make the most sense, giving us the best of both worlds, but they both assume that training to failure stimulates more muscle growth than stopping just shy of failure. After all, if there’s no extra growth stimulus from going all the way to failure, why would we ever do it at all?

Do we stimulate extra muscle growth by lifting all the way to failure?

Does Training to Failure Stimulate More Muscle Growth?

34% More Growth from Stopping Shy of Failure?

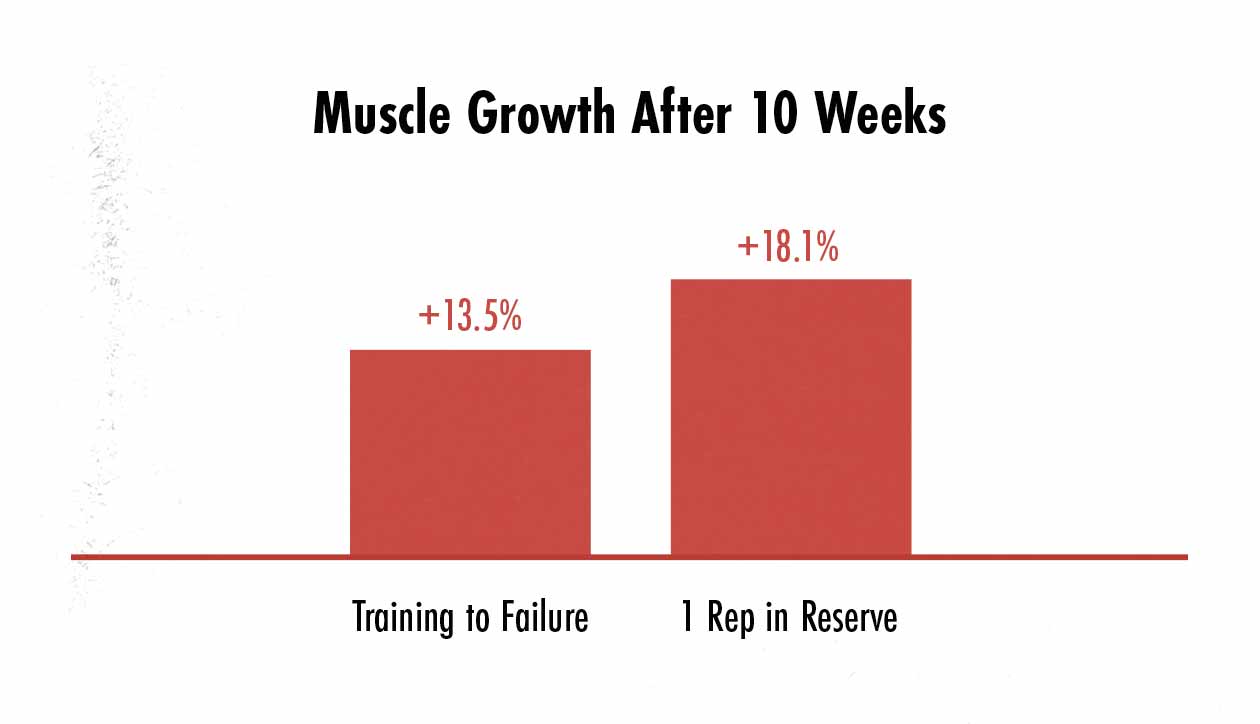

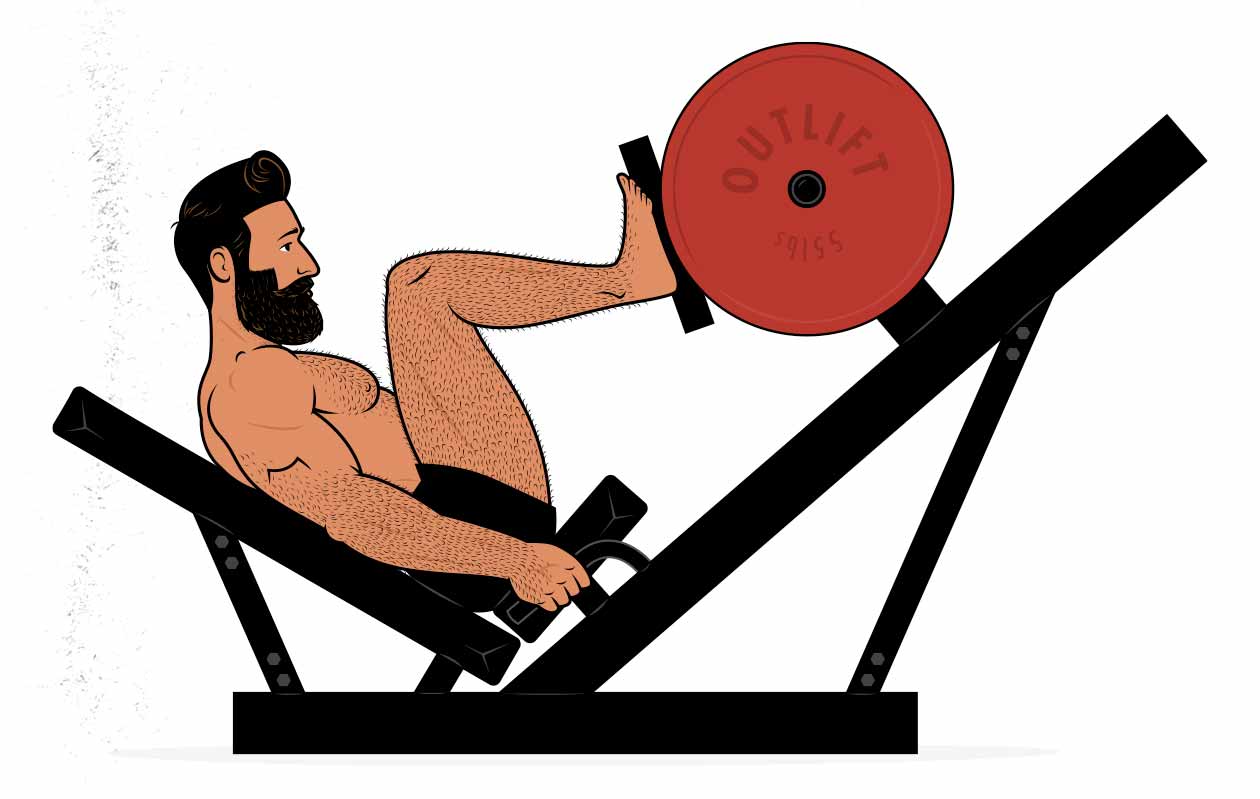

In a recent study by Santanielo et al, the researchers had the participants do one-legged leg presses and knee extensions. With one leg, they stopped just shy of failure, and with the other leg, they went all the way to muscular failure. This is about as perfect as a study could get, given that we’re comparing the muscle growth between limbs on the same person.

On the legs that lifted all the way to muscle failure, they saw a 13.5% increase in muscle size, whereas on the legs that stopped just shy of failure, they saw an 18.1% increase in muscle size. That means that by stopping their sets just shy of failure, they were able to increase their muscle growth by around 34%.

What makes this study even more interesting is that when training to failure, people were able to get an average of 12 reps per set, whereas when stopping just shy of failure, they were able to get 11 reps per set, meaning that even though the failure legs had a higher training volume—they did more total reps—they saw less growth than the non-failure legs. The other thing to note is that, at least on average, the participants were able to accurately stop their sets a single rep shy of failure. (I suspect it helped that they were taking one leg to failure. They got to feel exactly what failure felt like with that muscle group and with that rep range, allowing them to stop just shy on their other leg.)

So what we’re seeing here is that stopping shy of failure seems to increase muscle growth, even though it reduces total training volume. The catch being, of course, that just a single rep is left in the tank, which can take quite a bit of practice to master.

A Quick Review of All Failure Research

Now, this is just one study. At the time of writing, there are fourteen relevant studies. Some show more muscle growth from pushing harder and going closer to failure (Goto, Martorelli, Karsten, Tareda), others show a benefit to stopping just shy of failure (Santanielo, Carroll, Lacerda, Pareja-Blanco 2, Pareja-Blanco 3), and yet others show mixed results or no significant differences in muscle growth (Helms, Sampson, Pareja-Blanco 1, Nóbrega, Lasevicius). So, overall, it looks a bit foggy, right? Not quite. If we gaze a little deeper, a clearer picture emerges from the mist.

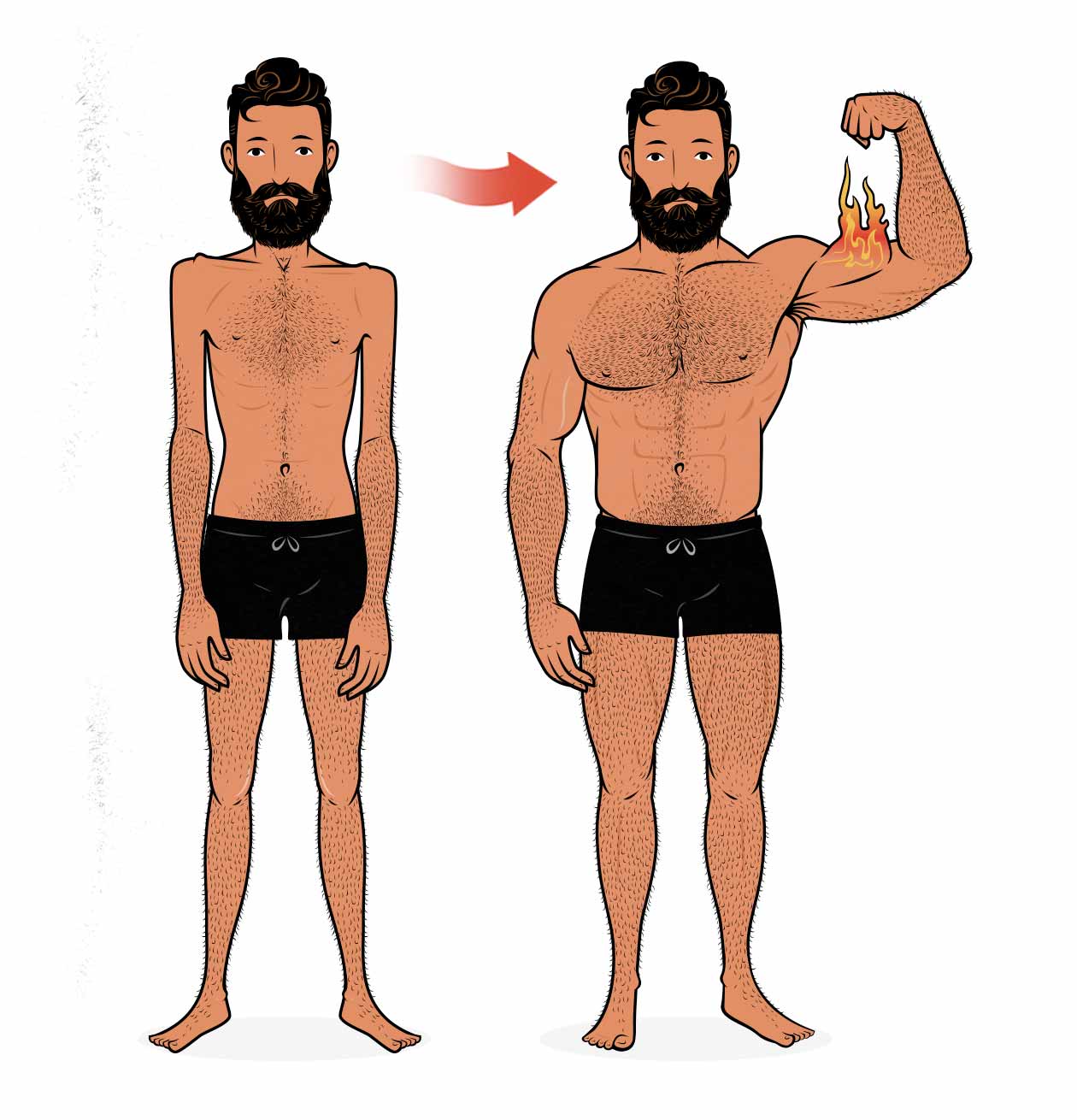

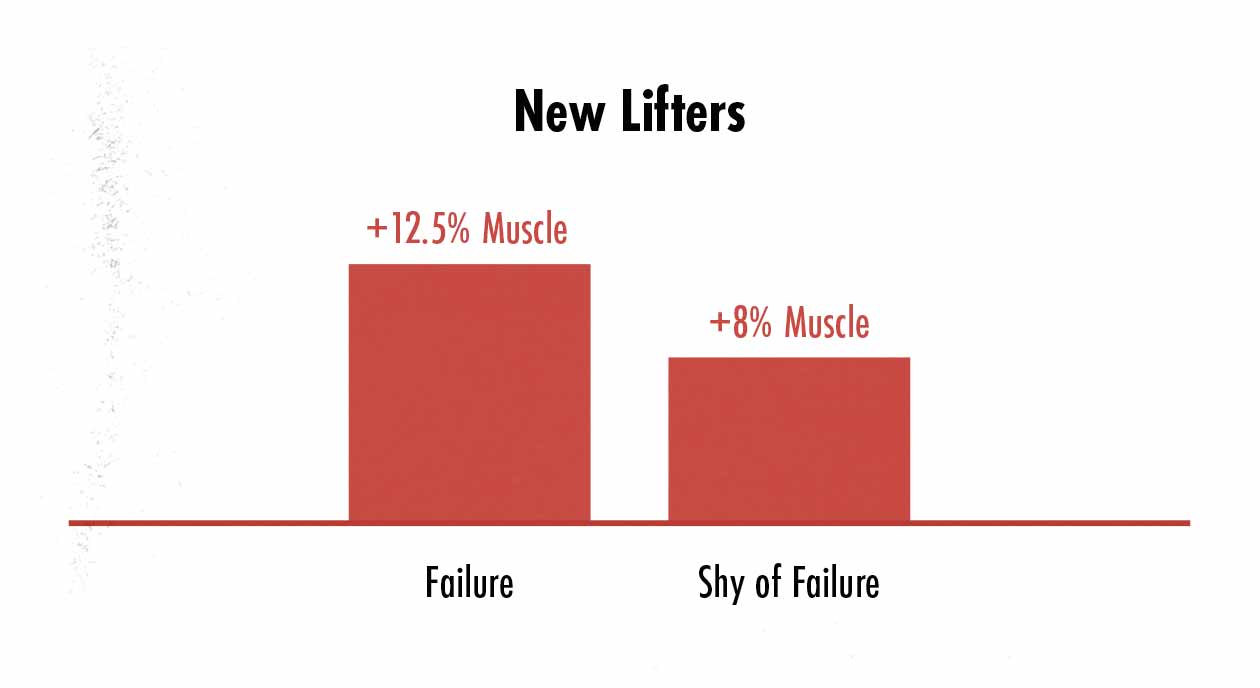

Greg Nuckols, MA, noticed that when untrained lifters were doing lighter isolation lifts, they stimulated more muscle growth by lifting closer to failure. When he crunched all of the numbers, the effect size wound up being quite large, too, with around 56% more muscle growth from taking those isolation lifts to failure.

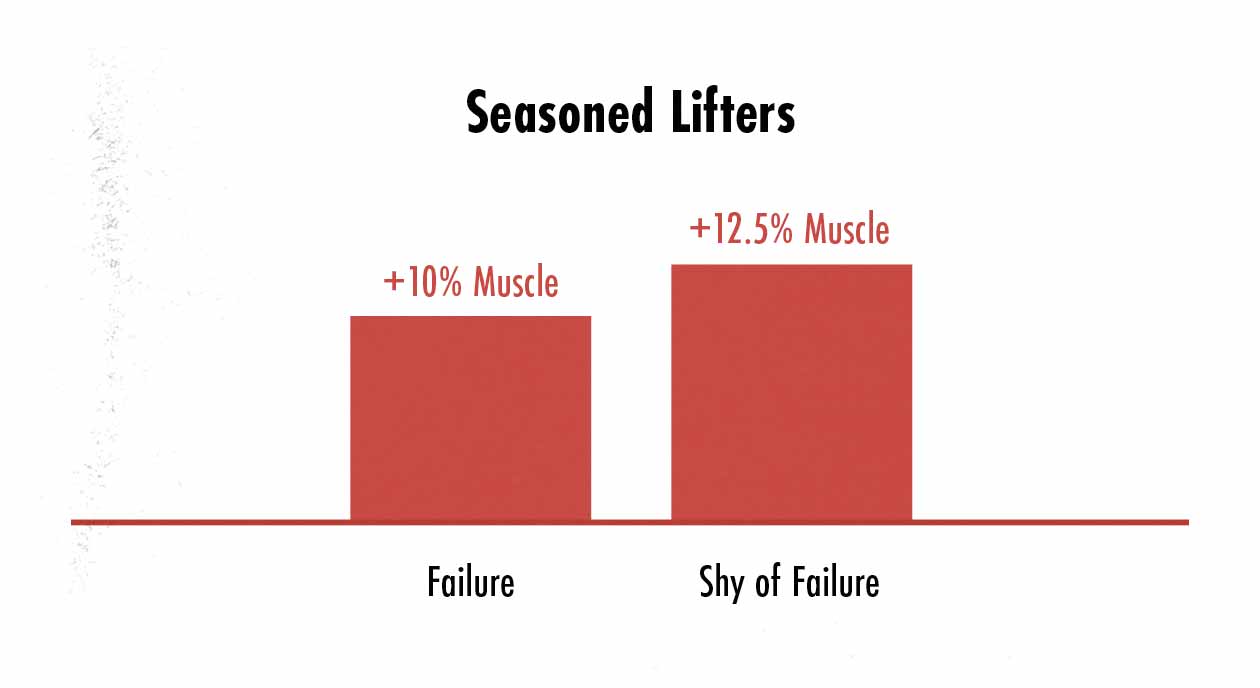

With intermediate and advanced lifters, though, the findings were almost the exact opposite. When seasoned lifters were doing heavy compound lifts, they built more muscle when they stopped shy of failure. Here the effect size was smaller, but there was around 25% more muscle growth from stopping sets shy of failure.

So what we’re seeing is that although there are situations where lifting to failure helps, there are also situations where it doesn’t. Here’s a rough breakdown of when it can be helpful to train to failure:

- Beginners: new lifters stimulate more muscle growth by lifting to failure.

- Seasoned lifters: intermediate and advanced lifters stimulate more muscle growth by stopping just shy of failure.

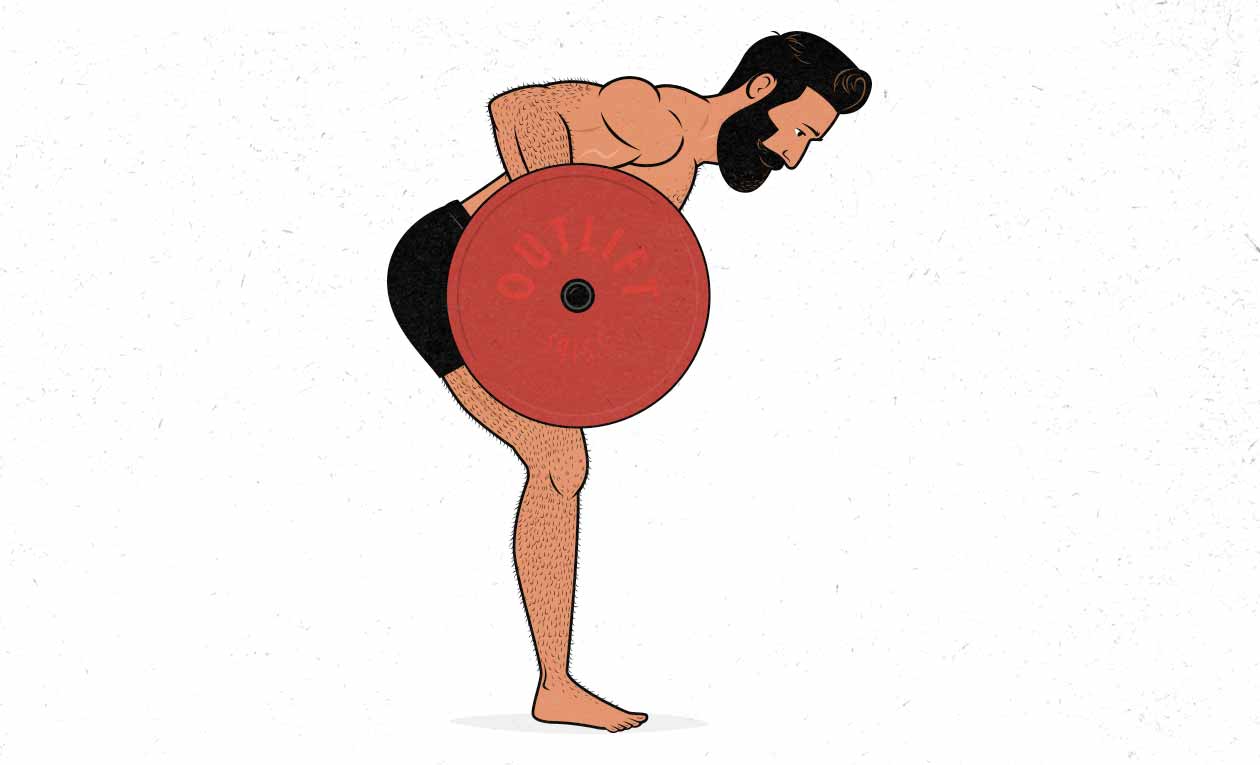

- Compound lifts: when doing the bigger compound lifts, we stimulate more muscle growth by stopping just shy of failure. So for squats, deadlifts, barbell rows, and bench presses, there’s less need to go all the way to failure.

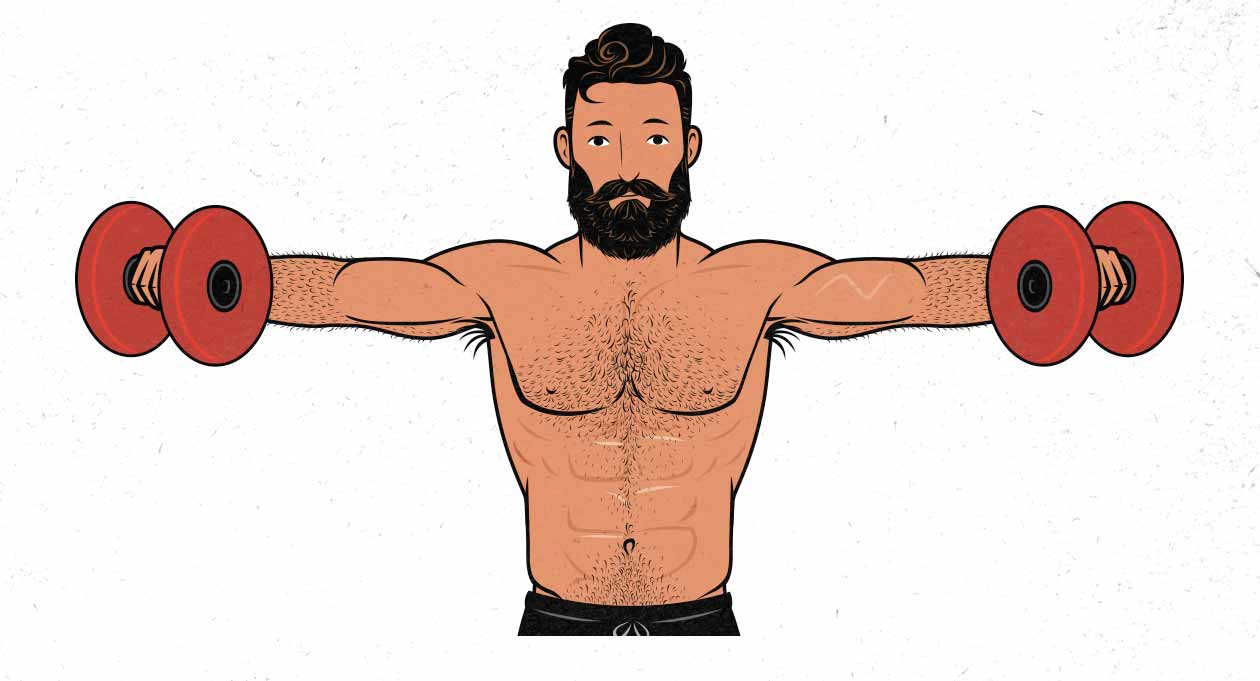

- Isolation lifts: when doing smaller isolation lifts, we often stimulate more muscle growth by taking our sets closer to failure.

- Heavier rep ranges: when lifting in heavier rep ranges, we stimulate more muscle growth by stopping shy of failure. So for sets of 1–7 reps, it can help to leave reps in the tank.

- Lighter rep ranges: it seems that as our rep ranges get higher, we stimulate more muscle growth by lifting all the way to failure. So for sets of 15–30, it helps to push harder.

Let’s dig a little deeper into these variables.

When Should You Train to Failure?

Should Beginners Lift to Failure?

Yes, beginners should practice lifting to failure, but mainly with their isolation lifts. It seems that beginners lack the coordination or experience needed to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth if they stop their sets shy of failure. As covered above, the best summary of the data comes from Greg Nuckols, as seen in his article about effective reps, where he concluded that new lifters build muscle faster by taking their sets all the way to failure. Now, that might sound like he’s recommend that beginners go to failure, but that’s not quite the case. There are other factors to consider, too, such as ingraining good lifting technique and avoiding injury.

I asked Greg what his advice for beginners was, and he responded with:

For training new lifters, I personally like to keep them far from failure on compound lifts, with the goal of teaching good technique, but also choosing single-joint exercises that will let them go to failure safely, getting them a bit of a pump.

Greg Nuckols, Stronger by Science

So if you’re a new lifter, it’s probably wise to stop your compound lifts before our technique starts to break down, which likely means stopping a couple of reps shy of failure. Then, as your technique gets better, and you’re able to push harder without your form breaking down, you can push your compound lifts a bit closer to failure. By that point, of course, you’ll likely be experienced enough that you won’t need to go all the way to failure, though, at least not on the majority of your sets.

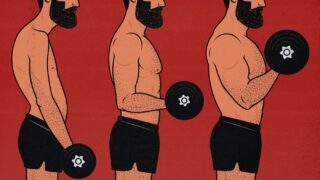

With isolation lifts, though, it’s the opposite. These are your opportunity to truly challenge your target muscles. If you want bigger arms, take your sets of biceps curls, triceps extensions, lateral raises, and so on all way to failure, that way you ensure that you’re stimulating maximal muscle growth. The same is true with every muscle group. If you’re eager to grow your legs, do some leg extensions and hamstring curls to failure. Then, as you get better at pushing yourself, becoming more of an intermediate lifter, you can ease back on training to failure, stopping just shy of failure on most sets, and perhaps saving failure for just the final set of each isolation exercise.

Should Experienced Lifters Train to Failure?

No, intermediate and advanced lifters shouldn’t lift to failure, or at least not by default. If we look at the research, intermediate and advanced lifters seem to benefit from stopping their sets just shy of failure, leaving 0–3 reps in reserve. By leaving reps in the tank, not only do their workouts become safer, they also become easier to do, easier to recover from, and they stimulate more muscle growth.

That’s not a hard and fast rule, though, just a loose rule of thumb. There’s nothing wrong with taking your final sets to failure, with pushing harder on your isolation lifts, or with taking sets to failure when lifting in higher rep ranges. In fact, lifting closer to failure in those circumstances may even stimulate more muscle growth.

So, for instance, best to stop your 6-rep set of squats shy of failure. But when doing a 15-rep set of lateral raises, you may stimulate more muscle growth by going all the way to failure.

The Problem of Estimating Reps in Reserve

One of the big disadvantages of stopping sets before reaching muscle failure is that most people underestimate how many reps they’re leaving in reserve. For instance, in this study, when asked to choose a weight they thought they could complete 10 repetitions with, most of the participants were able to get 15 reps before hitting muscular failure. That’s not enough to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth.

For another example, in this study, when asked how many reps they were leaving in reserve, most of the participants were off by at least a couple of reps. Again, this can create the problem of people not pushing themselves hard enough to stimulate much muscle growth.

On the other hand, when people lift all the way to failure, no, it might not be perfectly ideal, but at least it’s guaranteed to stimulate muscle growth. Yes, you might stimulate something like 20% more growth if you stopped exactly one rep shy of failure, but that’s not always easy to do. So by training to failure, at least you’re guaranteed to stimulate some growth.

Now, this doesn’t mean that people need to always take their sets to failure in order to guarantee muscle growth, it just means that we should sometimes take our sets to failure so that we’re constantly testing our estimations and improving our ability to gauge how hard we’re pushing ourselves.

Should You Take Compound Lifts to Failure?

This is a hard question to answer. Everyone is a bit different, and each lift has its own nuances to it. For example, depending on what your weakest link is, taking a low-bar barbell back squat to failure can be quite rough. If your lower back collapses under the weight and you wind up pinned under the bar, having to lower it awkwardly down to the safety pins, that can be hard on your spine, and something that you want to avoid doing every single set or every single workout. On the other hand, if your quads gas out long before your back does, and you’re able to lower it down to the pins while still maintaining a neutral spine, well, that’s entirely different—it’s much safer.

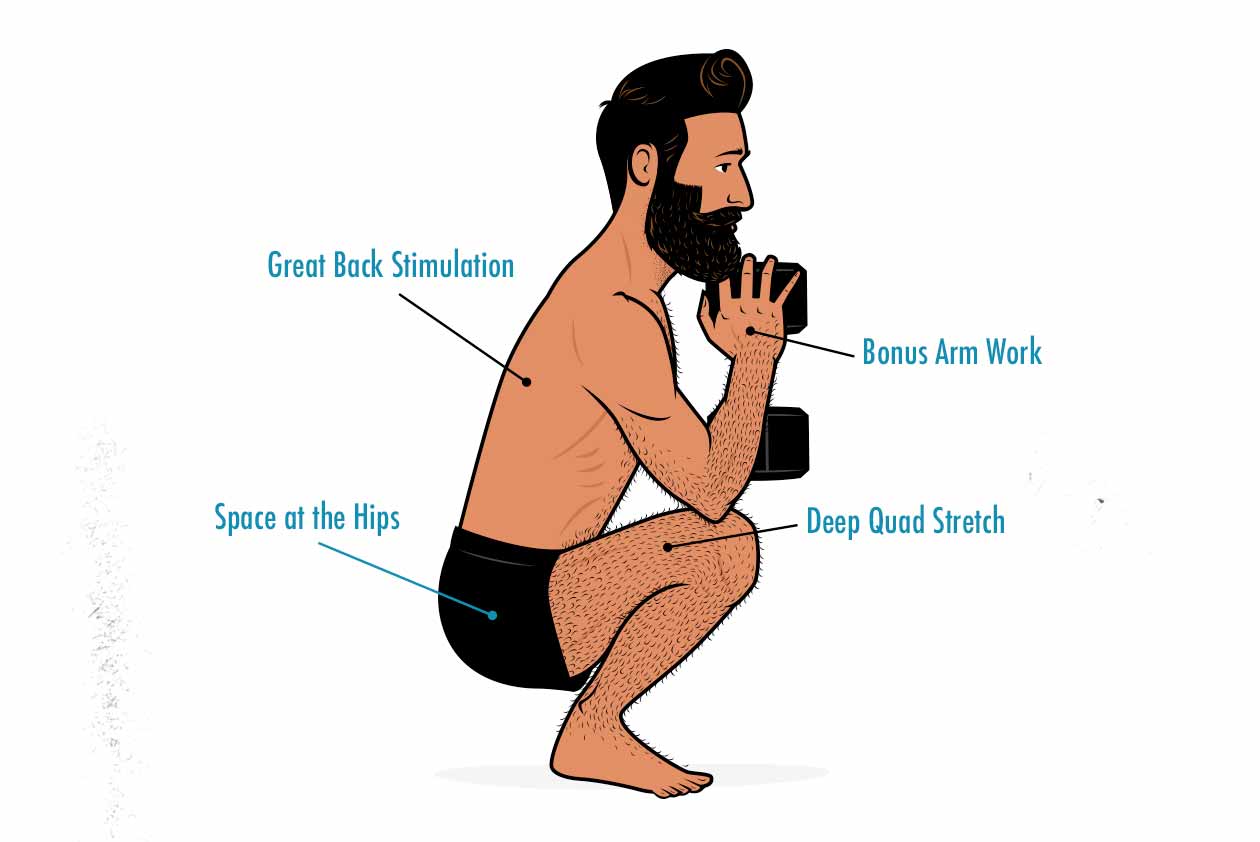

Different lifts have different dynamics, too. If we look at something like a front squat, where any deviation in spinal position causes us to dump the bar forward, we see that it’s a lift that can’t really be cheated. The racked position we hold the bar in is also a safety feature, designed to make it easy to dump the bar in an emergency. If we can’t lower the bar safely to the pins, we can just push the bar off our shoulders and step back. In fact, if you’re using bumper players, you don’t even need to lift with safety pins. It’s a squat variation that makes it safer to push ourselves harder.

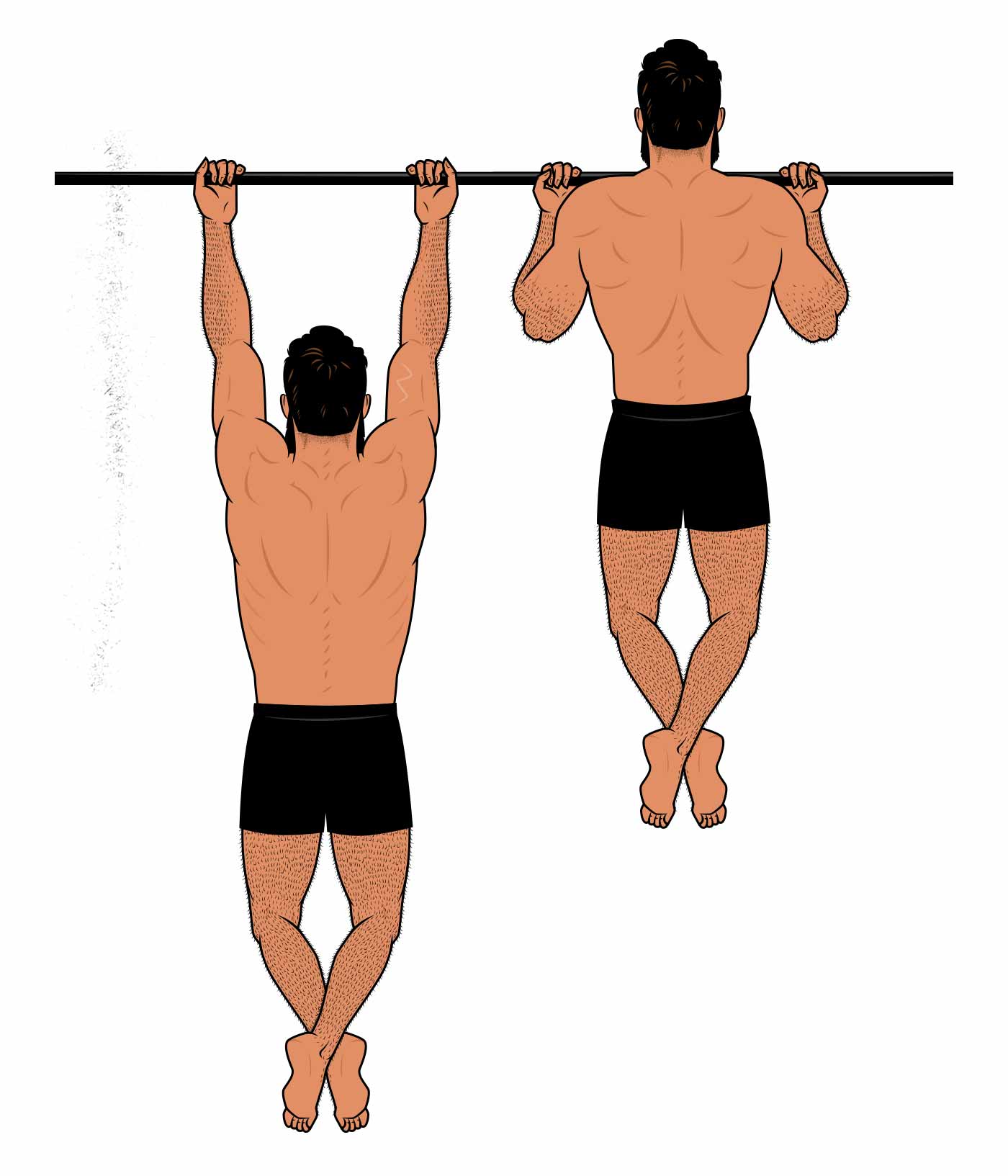

Another example of a lift that’s well-suited to being pushed harder is the chin-up. If you can’t bring your chin to the bar, you lower yourself back down, curse a few times, and that’s that. There’s no real harm in taking the set all the way to failure. Plus, since the sticking point is when our muscles are in a contracted position, we aren’t even causing all that much muscle damage by taking our sets to failure (as opposed to something like a bench press, where we fail our sets with our muscles at longer muscle lengths). More on that here.

Now compare that chin-up example against the bent-over barbell row, where we’re more likely to fail in our spinal erectors. Is that dangerous? Not necessarily, especially if you’re strong at your deadlifts. You might be rowing with 225 pounds, deadlifting with 415 pounds. The load is so much lighter that there’s little risk in it injury your back. But the fatigue the lift can generate is tremendous. If your lower back is giving out at the end of every set, you’re going to generate a ton of fatigue in your spinal erectors, which can make it harder to push yourself with your deadlifts, squats, and overhead presses. If you want to take your rows all the way to failure, then, you might want to choose a chest-supported row variation.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, if your technique on the compound lifts isn’t rock solid, then it’s probably not the best time to be taking those sets to failure. When a newer lifter takes their final sets to failure, technique breakdown can be severe, and that may (debatably) wind up ingraining poor form. It can also increase the risk of injury. Better to master the lift and then push yourself closer to failure.

Should You Take Isolation Lifts to Failure?

With compound lifts, we have a number of safety and technique factors to consider. With isolation lifts, though, they’re often lighter, safer, and simpler, allowing us to push closer to failure with less risk of injury. Plus, since we’re less likely to fail with our spinal erectors, the fatigue that isolation lifts cause tends to be easier to manage as well.

For example, let’s say that you do a few sets of the bench press, never quite reaching failure, and likely not bringing your triceps anywhere close to failure. That can be a good time to toss in some skull crushers, and there’s little reason to avoid failure when doing them, especially on your final sets. The same is true with following up chin-ups with biceps curls, or overhead presses with lateral raises. Assuming these lifts aren’t hurting your joints, there’s little harm in pushing harder, and even if you take them to failure, they won’t generate all that much overall fatigue.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, if you’re a newer lifter and you aren’t taking your compound lifts to failure, then there’s a real risk that you aren’t challenging your muscles enough to provoke muscle growth. That’s where taking isolation lifts closer to failure becomes all the more crucial, since they give us an opportunity to truly push ourselves.

The Minimalist Approach

One of the main advantages of stopping our sets shy of failure is that it allows us to recover better. We preserve more strength from set to set, we preserve more energy as we move deeper into our workouts, and we inflict less muscle, allowing us to train our muscles more often. but many of these advantages disappear if we’re only doing a couple of sets per exercise, a couple of exercises per workout, and a couple of workouts per week. If we don’t need those recovery advantages, there’s more of an argument for pushing ourselves harder each set.

That’s why some minimalist approaches to training, such as Reverse Pyramid Training, can work well when taking our sets closer to failure. Perhaps not failing our reps, but at least lifting until we don’t have any reps in reserve, stopping just, just shy of failure. Is that the very best way to build muscle? No. But it’s highly efficient.

Plus, when doing minimalist programs, it’s more important than ever to make sure that you’re challenging yourself enough to stimulate growth. When you’re taking all of your sets to the brink of failure, you can get a very clear idea of whether you’re actually getting stronger from workout to workout. If you aren’t, you might need to start doing more sets per exercise. That’s crucial feedback that can be hidden by always staying further from failure.

Always Outlifting Yourself

The main disadvantage of stopping shy of failure is that it can often get in the way of progressive overload. If you’re following a good program, writing down how much weight you’re lifting, and showing up every working fighting to lift more weight or eke out more reps, then it’s not an issue—it’s perfectly fine to stop shy of failure.

The problem is when people get in the habit of stopping their sets when they get painful or hard. In order to keep stimulating muscle growth, we need to continue challenging ourselves, and that will often mean that our workouts go through periods of getting harder. This is where the lifters who train to failure often win out, since they always exert themselves fully, and so any improvement in size or strength is immediately visible in the extra reps or extra weight that they can lift. Any lack of progress is also visible. If you’ve failed halfway through your seventh rep for five weeks in a row, you know that you’ve hit a plateau.

Because training to failure takes the subjectivity and guesswork out of our progress, it’s often a more idiot-proof way of training. Not that it’s better, just that it’s simpler. If that’s something you think you might benefit from, and especially if you’ve hit a plateau, you might want to start taking the final set of each lift to failure. If you aren’t improving from workout to workout, or at least from month to month, then you need to adjust your workout program or your diet (as eating enough protein and calories is another crucial part of building muscle).

Summary

Overall, what we see is that for intermediate lifters, it’s usually best to stop just shy of failure, leaving somewhere between 0–3 reps in reserve. Maybe on heavier compound lifts that means leaving 3 reps in reserve on the first set, 1 rep in reserve on the final set. Then, with isolation lifts, maybe that means leaving 1–2 reps in reserve on earlier sets, 0 reps in reserve on the final set.

However, there are a few situations where lifters benefit from pushing even harder and lifting to failure:

- Beginners aren’t great at contracting their muscles yet, and so they can benefit from doing simple isolation lifts and taking them all the way to technical failure.

- When training with lighter loads, it’s often better to lift to failure. This can be especially important when doing bodyweight hypertrophy workouts, such as when doing high-rep sets of push-ups.

- When doing minimalist workout programs with just a couple of sets per exercise, just a couple of exercises per workout, and just a couple of workouts per week, it can help to push harder, taking our sets right to the brink of failure.

- It can often be helpful to take at least some sets to failure some of the time. Not because it stimulates more muscle growth, but because it helps us learn how many reps we’re actually leaving in reserve when we stop shy of failure.

As always, if you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. We also have our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program and Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program for skinny beginners. If you liked this article, you’ll love our full programs.

Nice article Shane. Very informative and cleared up many confusions.

What I understand from it is that going for maximum possible reps without technique breakdown is best bet on compound lifts for novice as well as intermediate lifters. Right?

Secondly, please correct my extrapolation: when doing a compound lift for 5×5 on same weight for all sets, 5th rep of each set should be the last rep possible with safe technique so that technical failure is avoided even if it means that 6th rep could be performed partially with safe technique which indirectly means like half rep in reserve. Thanx

Hey Farhan, thank you!

As an intermediate lifter, when doing heavy compound lifts with the goal of gaining muscle size, it’s often best to stop before hitting technical failure. That might mean stopping just shy of failure or, depending on the program, maybe stopping 1–3 reps shy of failure. It’s just that pushing all the way to failure probably isn’t ideal, at least not all that often. (It might be necessary to lift to failure sometimes so that you can have a better idea of where failure is and how far away from it you’re stopping.)

As a beginner, stopping shy of failure on compound lifts isn’t ideal for building muscle in the shorter term, but it does increase safety, reduces fatigue, reduces soreness, and it makes it easier to improve our lifting technique. It’s an investment in longer-term results. It allows us to build skills that can carry us through the intermediate stage. Then, to ensure maximal short-term progress, we turn to simpler isolation lifts where it’s safer and less fatiguing to push our sets to failure.

5×5 isn’t normally done with the goal of gaining muscle size. That’s more of a strength training thing. With hypertrophy training, probably better to do fewer sets of higher reps. More like 3×12 or 4×8. But if you’re doing five sets of five repetitions, that’s a heavy rep range with big compound lifts, so you’d probably want to leave around 3–4 reps in the tank on that first set so that you can still get around 5 reps on that final set. If you go too hard on the first set and wind up doing, say, 5 reps, 4 reps, 4, 3, 2… well… the reps there are getting very low by the end. You won’t stimulate much muscle growth that way.

Also, your questions are good ones, and I’ve edited the summary to answer these questions in the article itself 🙂

Thank you for your quick response..

Shane: great lunch-time reading, thank you! A comment and question:

Thanks for highlighting the issue of safety. For intermediate lifters (me) the weights are getting up there, and it becomes really important to think about how you can “fail safe”. For example, I am personally not willing to approach failure of any type with back squats, or the barbell press without a spotter, but I will occasionally test myself on the dumbbell press because I can fail safely by simply dropping the weights. (The gym hates that but it’s rare and they still want my money.) Live to work out another day!

Question: With each passing year of age and experience, it takes a little longer to warm up. I can’t realistically do one or two warm-up sets and then approach my maxes; my joints and muscles just won’t. On the other hand, laddering up does take energy, so my failure or near-failure point often occurs before there’s a chance to progressively overload. Thoughts on this? It’s resulted in a kind of plateau on some lifts, most noticeably presses of all kinds (especially shoulders). Thanks!

Hey Doc G, thank you! 🙂

If you want to take a barbell bench press to failure, you can set up with safety bars in a power cage or squat rack. We’ve written about that here. But, yeah, perfectly fine not to, especially if you’re taking some other chest exercises to failure sometimes.

I hear ya about needing to do more warm-up sets, especially when lifting in lower rep ranges. I’ve been working towards a 315 bench this year, starting with gaining size in higher rep ranges and now trying to transfer that strength to lower rep ranges. When doing 13 reps with 225 pounds, the warm-up sets were manageable. Now I’m doing sets of 5 reps with 275 pounds and the warm-up sets are a real drain. Doing a final warm-up set of, say, 3×245 to warm up for 5×275 is still pretty tiring. And between sets, I find myself needing fairly long rest periods, otherwise it just doesn’t feel safe to attempt another set with 275.

An easy solution in situations like that is just to get rid of the low-rep sets. Instead of sets of 5–6 reps, moving up to sets of 8–15 reps instead. That can be a real pain with squats and deadlifts, but if your problem is with presses, you might have good luck doing sets of 8–10 on the overhead press and sets of 10–15 on the bench press.

The other thing is not to be afraid of doing fewer reps in the final warm-up sets. Get some blood flowing with 50% of your working weight, doing maybe 10 reps. But as you get closer to 80% of your working weight, just do 1–3 reps, you know?

Finally, the overhead barbell shoulder press is notorious for producing brutal plateaus. You really need to get some practice grinding out those final reps. It’s a lift where you might want to get comfortable really pushing yourself (provided you can do it safely). There’s a skill you need to develop where you grind through that sticking point, where the barbell is at about shoulder height.

The other thing that can help with the overhead press is experimenting with reverse pyramid rep schemes, doing three sets every workout: a heavy set, a moderate set, and a lighter set. We’ve got an article on reverse pyramid training here.

Another way to break through overhead pressing plateaus is with some closer-grip bench pressing, bringing the barbell down a lower on your chest. That way you’re training your upper chest and front delts under a greater stretch, which can be great for bulking them up, as explained in this article. As a bonus, that’s a great way to improve your standard bench press, too.

And make sure to include some overhead extensions and skullcrushers in your routine. Skullcrushers in particular are a common tool that powerlifters use to bust through bench press plateaus.

Hi Shane, as for warm up sets, I want to share my experience.

Before anything, let me be clear that I am not lifting anywhere near your numbers or poundages of other people on this forum, but sure my numbers are very challenging for my strength level.

Comming to point, traditional warm ups as discussed in above comments are really tiring and often lead to sub-par performance on working sets.

Better option is to go for ramp up sets. For a target working set of 5 reps, gradually build up all the way using 2-reps sets, when reaching close to work sets, do singles and a final single at a weight that is 5%-10% ahead of work set. It won’t be tiring at all and will prime up the CNS. Now working sets shall feel quite easier.

I would still call those warm-up sets, but that’s just us using different words. I agree. That’s a great way to do it 🙂

Hey Shane

Awesome article as always.

Is b2B considered a minimalist programme? Also does this advice somewhat replace the 2 reps in tank rule?

Hey Zen, thank you! 🙂

The workout routine in b2B isn’t minimal, no. It’s designed to be ideal for stimulating muscle growth, not to be as short, quick, or simple as possible. We take the approach of gradually mastering the big compound lifts (ideal for the longer term) while also including plenty of isolation lifts that allow us to push ourselves harder (ideal for the shorter term).

We recommend keeping two reps in the tank (aka two reps in reserve) for the compound lifts, and even though that isn’t quite ideal for stimulating muscle growth for a beginner, the isolation lifts are there to make up for it. That gives us the best of both worlds, giving us fast muscle growth right out of the gate while also setting us up well for the intermediate stage, as well as building a good foundation of strength.

We also try to start with simpler compound lifts, such as starting with the goblet squat instead of the barbell back squat. Not only is it more of a “brute strength” lift, where there’s less coordination involved, but we’re also less likely to be limited by our stabilizer muscles, such as our spinal erectors. The goal there is to make it easier for beginners to push themselves harder, so that even with a couple of reps in the tank, the sets can still be plenty challenging on the target muscles (in this case mainly the quads and glutes, but also sometimes the upper back and arms).

With the isolation lifts, though, yeah, as more of this research has been coming out, Marco and I have been talking about recommending pushing closer to failure. I think on the isolation lifts, if you’re confident that you can do it safely, you might want to take your finals sets to failure while doing the b2B program. With the squats, bench presses, deadlifts, and other big compound lifts, though, keep those two reps in the tank. Most of the time, anyway—no harm in taking some sets to failure now and then just to see how many reps you’ve actually got in the tank.

I friggin love this, Shane! Another great article. Super informative. Good stuff! Sidenote: after more than a year, I’m back in the gym! Feels SOOOOO good haha, and I feel fully recovered and SO stoked to be back to lifting. Life post-divorce is finally stabilizing a little bit, I have more of a routine, figured out job stuff, and I’ve done a bunch of running and bodyweight stuff (ran a half marathon and a full marathon, and got up to workouts of 100 pushups and 100 pullups last year!) in the off-season which has kept me healthy and maintained a fair amount of muscle. All that being said though, I missed lifting and getting back at it for the last couple weeks has been incredible (I knew I was ready when I literally had a great dream about bench pressing bahaha)

Thanks, Ricky, and glad to hear it, man—that’s sweet!

100-pull-up workouts and full marathons?! Damn!

Ahaha I hear ya. Sometimes I’m kind of lukewarm about lifting. I mean, I have a decent enough time of exercising, but it’s just a habit I go through to stay strong and healthy, you know? But then other times, the dreams kick in, and I know it’s time to do another bulk / fight to hit a new milestone, and I just absolutely love it 🙂

“One of the big disadvantages of stopping sets before reaching muscle failure is that most people ‘overestimate’ how many reps they’re leaving in reserve”, shouldn’t it be ‘underestimate’ instead? People thinks is near failure (0 RIR) while actually they have a few more.

Hey Thomas, good catch. Fixed. Thank you 🙂

I think RPT is done just shy of failure, not technical or absolute failure. According to RPT article by Martin Berkhan, he states: “So instead of training to failure, I told clients to exert maximal effort each set. This, I explained, meant they should do as many reps as possible – using good form – and terminate the set when they doubted their ability to complete another repetition.”.

To me, AMRAP using good form is training just shy of failure.

Hey Lukas, what you’re saying can be right, yeah. But reverse pyramid training (RPT) is just a rep scheme. There’s no single correct way to do it. You can do it way shy of failure, just shy of failure, go all the way to failure, go past failure. As long as you’re going from heavier sets to lighter sets, it’s still reverse pyramid training.

As for how we SHOULD do reverse pyramid training, I think your suggestion is a good default. I think stopping just shy of failure is a good way to do it, especially on the lighter sets.

I agree with you about what As Many Reps As Possible (AMRAP) should mean. That’s how we often use the term as well. And that’s what I do in my own training. I do as many reps as we can.

Sometimes we’ll leave some reps in the tank when doing AMRAP, though, depending on what we’re trying to do. For instance, if someone is doing chin-ups, we might tell them to do AMRAP, leaving 1–2 reps in the tank. So if they can do 10 chin-ups, they’ll stop at 8–9 chin-ups. That way we don’t need to get fussy with the loading (doing assisted chin-ups to get into a higher rep range or adding weight to get into a lower rep range), but we’re still ensuring that people are training hard enough.

“But reverse pyramid training (RPT) is just a rep scheme” – Totally agree with that. What I wanted to say is that RPT using AMRAP and good form is the most efficient way to train this scheme well. Going either to technical or absolute failure will always decrease my performance, hence the volume of training. I experienced that a lot, it’s just quite a skill to be able to recognize when to stop a rep at the appropriate moment.

Anyway, tons of great stuff I learnt on your website. Thank you 🙂

Hi Shane,

Thanks so much for your informative article.

However, what if I’m only working out at home and I only have 2 x 20kg dumbbells.

For my leg days, I do the routine listed below, but my grip and arms are failing me before I come close to failure for my legs. Is it still effective and optimal for muscle growth even though I don’t bring my sets close to failure?

Squats: 4 x 10 reps.

Deadlifts: 4 x 10 reps.

Split squats: 4 x 10 reps.

Thank you so much in advance.

Hey Kevin, my pleasure, man!

20kg dumbbells can be quite versatile. Not as versatile as having adjustable dumbbells, but there’s still a lot you can do.

Check out our article on progressive overload. It answers all of your questions in detail.

Long story short, you need to challenge your muscles to stimulate muscle growth. You don’t need to go all the way to failure, but you do need to challenge yourself, and you do need to increase that challenge as your muscles grow bigger and stronger.

Instead of sticking to a strict rep range, I’d recommend trying to progressively overload your reps. If you can do 10 reps this week, try for 11 reps next week. And then 12 the week after that.

Then, when the reps get so high that you’re working your conditioning more than your muscle strength, switch to a harder variation. For example, when you’re doing squats for sets of 15 reps, switch to split squats or Bulgarian split squats. When you’re doing those for 20 reps, maybe switch to reverse Nordic curls.

Same thing with deadlifts. When the reps get too high, switch to kickstand Romanian deadlifts. When the reps get too high again, try Nordic curls.

It should be noted that the results found by Greg Nuckols (the review this article is based on) is somewhat an outlier. Two recent meta-analysis investigated training to failure and both reached the exact same conclusions. There were no significant differences for hypertrophy in general, even after subgroup analysis of trained and untrained individuals. They also found that training to failure was favourable in resistance trained individuals when volume wasn’t equated (contradicting the results of Greg Nuckols).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2021.01.007

https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003936

Thanks for this, man! I’ll check it out. I’ll also ask Greg about it 🙂

Cool. I also want to know why Greg got different results.

[…] good way to build muscle (study, study, study). Neither is low-volume training (systematic review). Taking sets to total muscle failure doesn’t help either, except with isolation lifts for beginner lifters (study, […]