The Dumbbell Fly Versus the Cable Crossover

One of the more common questions we get is whether the dumbbell fly is a good lift for building a bigger chest. Some have heard that the dumbbell fly is dangerous, others have heard that it doesn’t challenge our pecs enough at the top of the range of motion. Not surprisingly then, a lot of people think that the cable crossover is the better variation, given that it challenges our pecs throughout the entire range of motion and isn’t as hard on our shoulders.

Is that true? If you’re trying to build a big chest, is the cable crossover really better than the classic dumbbell fly?

Introduction

There are quite a few compound lifts that train the chest, ranging from push-ups to the bench press to weighted dips. An important thing to note is that most people fail the bench press because their chests give out, meaning that their chests get more than their fair share of the growth stimulus compared to the other muscles. Plus, most people fail at the bottom of the lift, when their chests are in a deep stretch, meaning that their chests get an incredibly large growth stimulus.

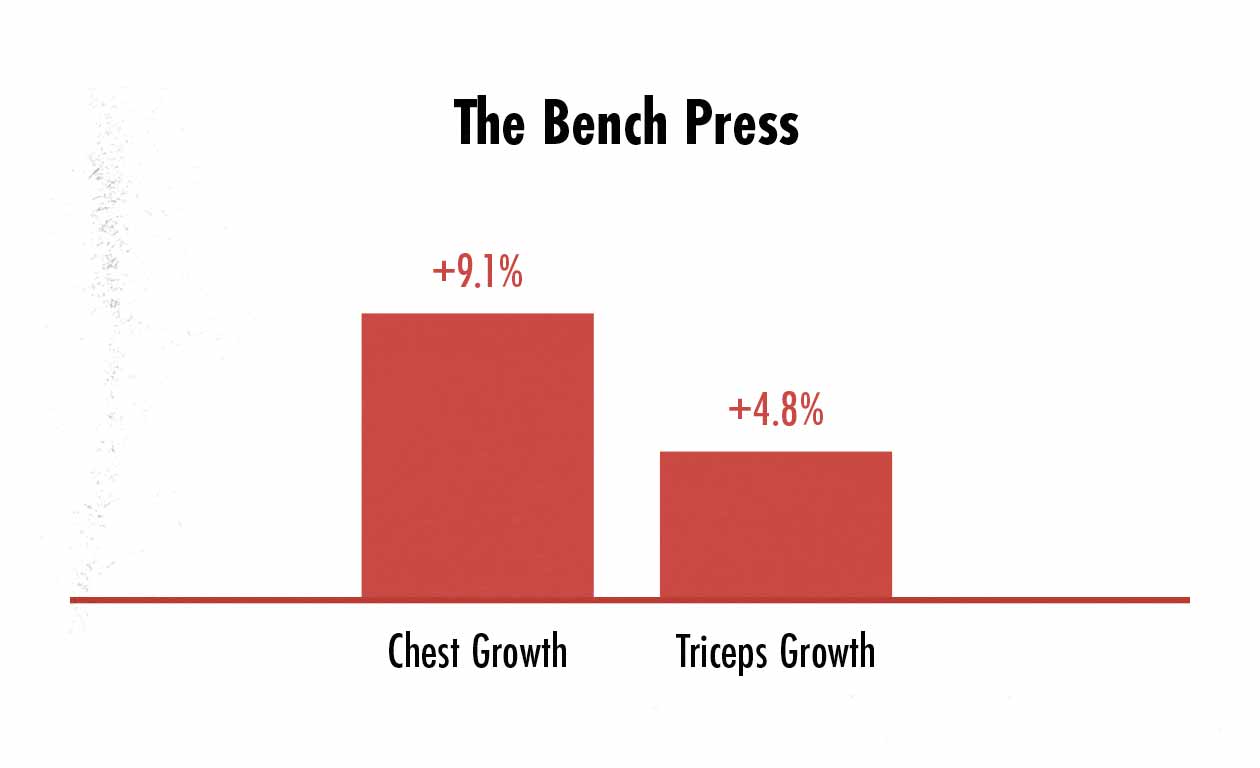

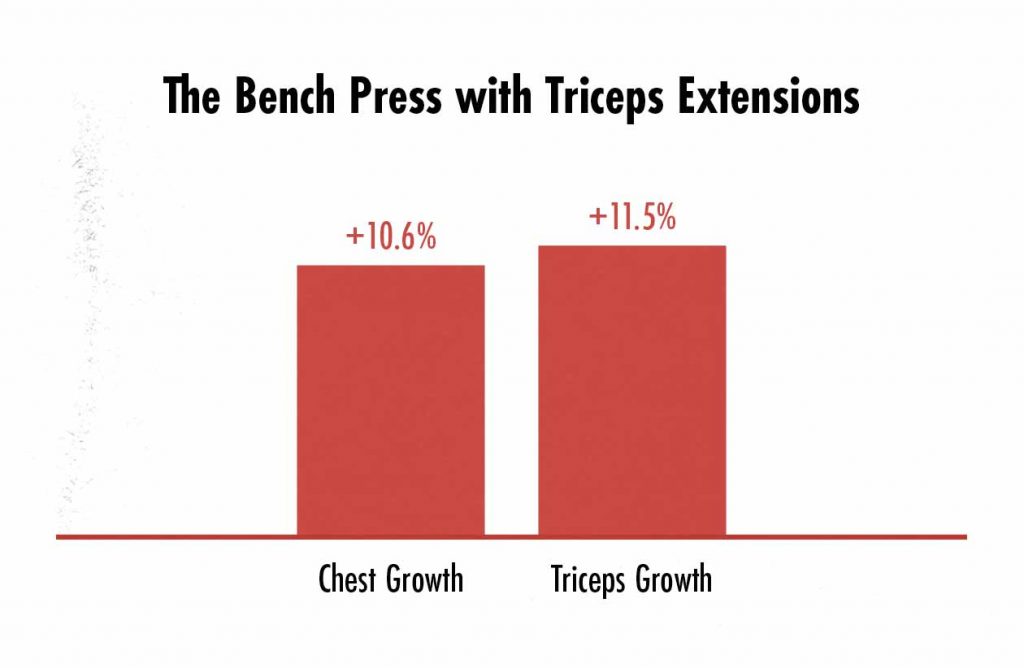

As a result, if we look at the average muscle growth from the bench press (study), the chest grows at full speed and the triceps lag behind, like so:

So for the average person, the chest grows quite well from doing the big compound lifts, and it’s their triceps that need the isolation lifts. This is especially true if you use dumbbells. The dumbbell bench press is even more chest-dominant than the barbell bench press.

If we look at what happens when we add triceps extensions to the bench press, we see muscle growth even out between the chest and triceps, like so:

So before we compare different types of chest fly, keep in mind that you might not need them. You might do just fine by doing the bench press, push-ups, and dips, and then maybe adding in some overhead triceps extensions to catch your triceps up.

But that’s not always the case. Sometimes people fail the bench press because their shoulders or triceps aren’t strong enough. That’s more common when using a narrow grip (which makes the bench press harder on the shoulders) or if they shorten the range of motion (which reduces the stretch on the chest).

It’s also fairly common for skinny guys with shallow ribcages to have trouble bringing the barbell all the way down to their chests when doing the bench press. This can put us in a position where we’re doing the bench press with a partial range of motion and our shoulders are losing stability at the bottom. It’s the bottom of the bench press that stimulates by far the most chest growth, so if we’re skipping that portion, our chests can lag behind.

In my own case, I gained a good thirty pounds before I was able to bring the barbell down to my chest without my shoulders losing their positioning. Fortunately, thanks to the dumbbell fly, my chest developed just fine, even before I was able to bench press properly.

Whatever the reason, it’s fairly common for people to struggle with lagging chests (or lagging upper chests). And besides, even if our chests are growing just fine, we might want to raise our training volume even higher, speeding up growth even more. That’s where the chest fly comes in.

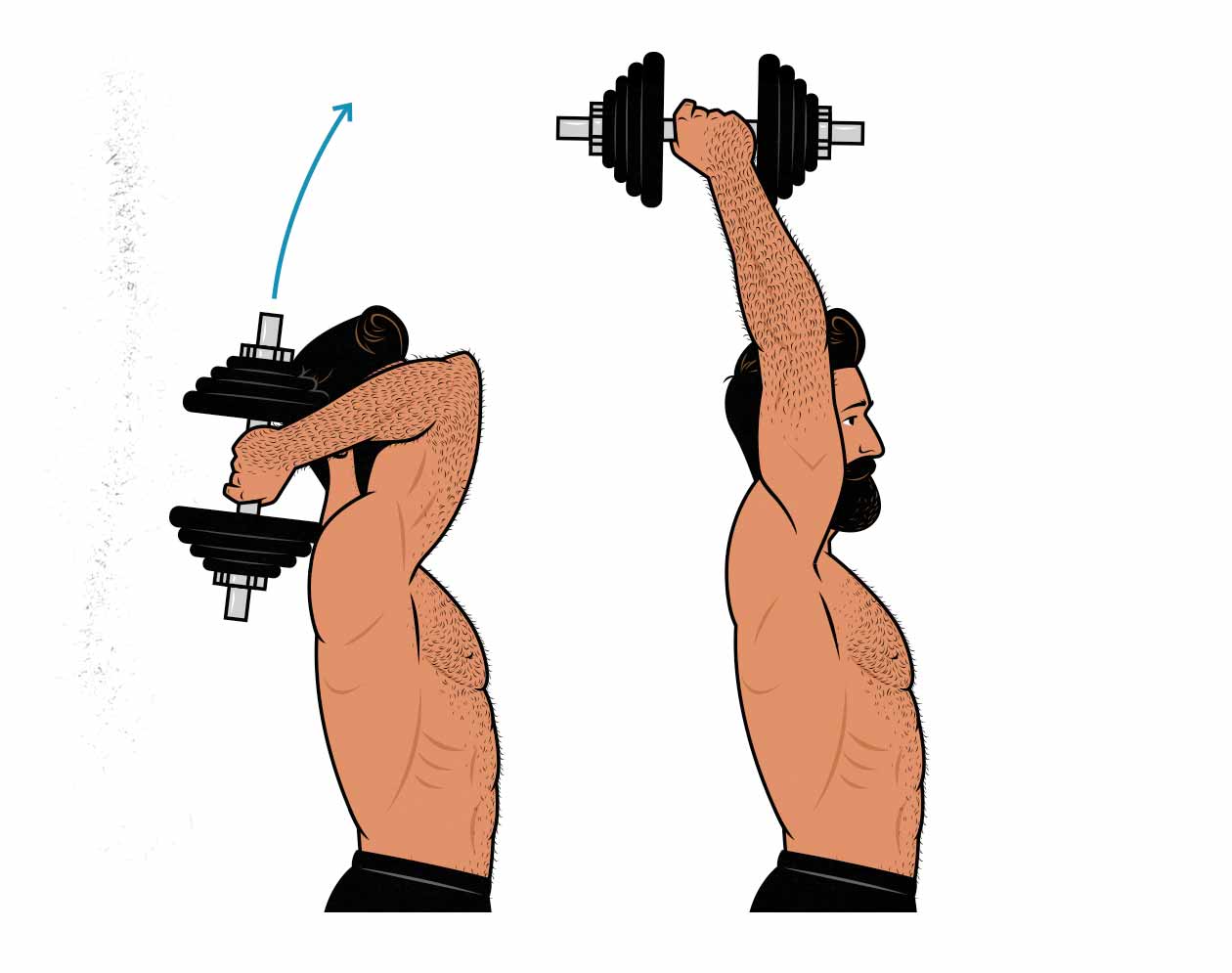

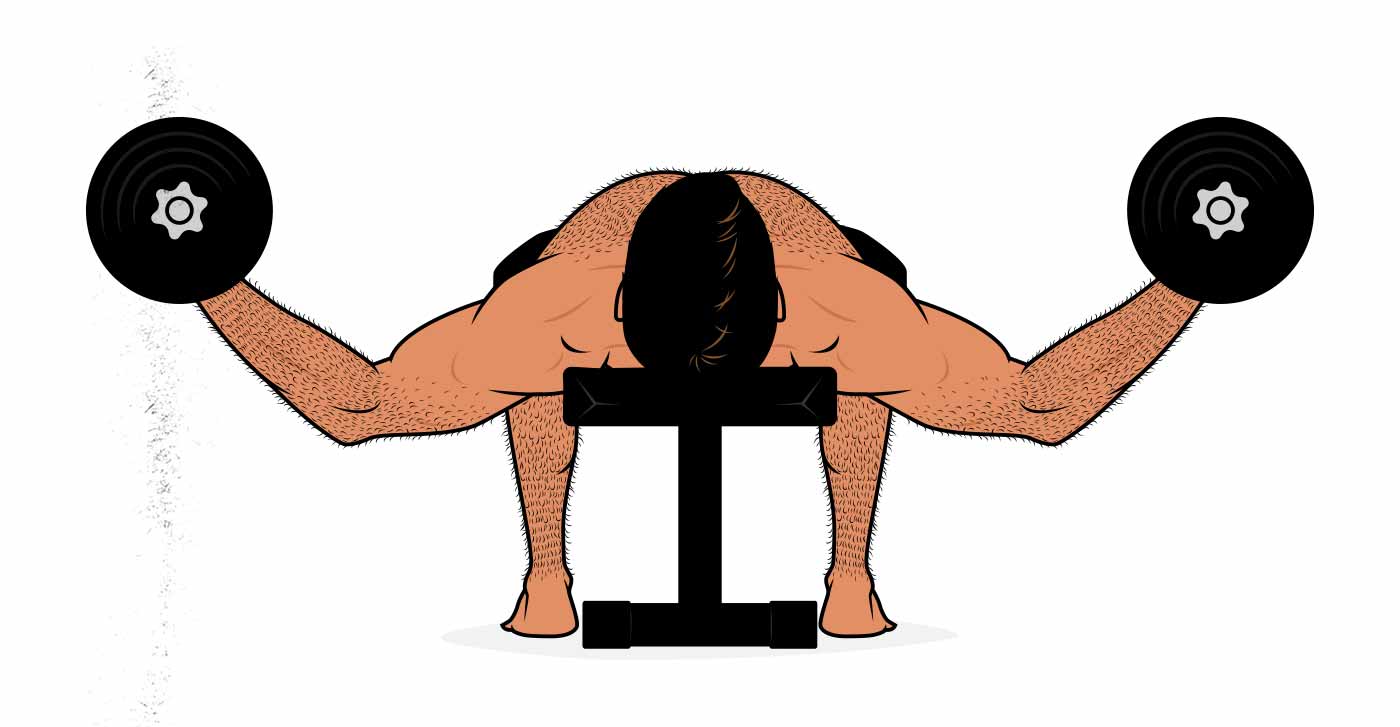

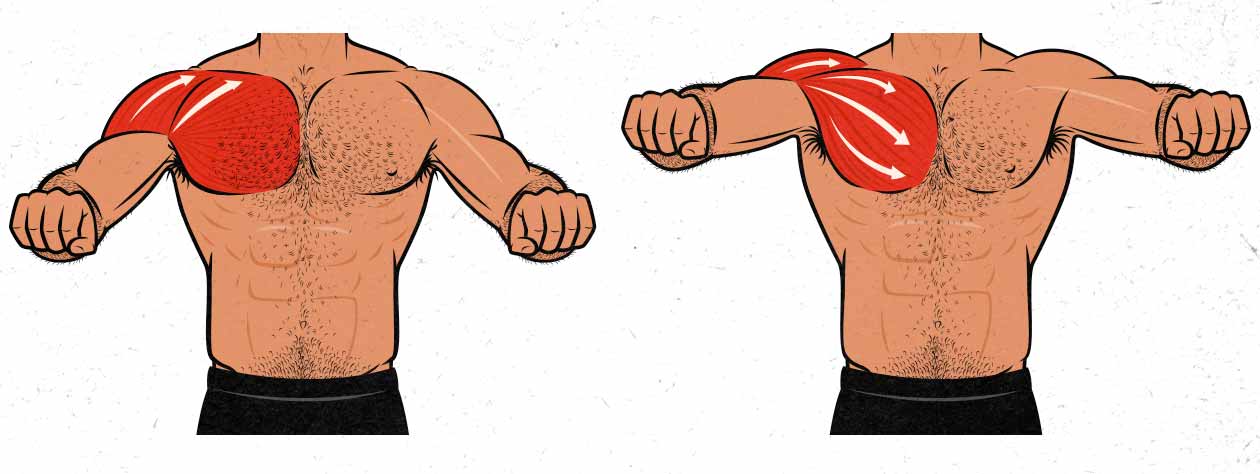

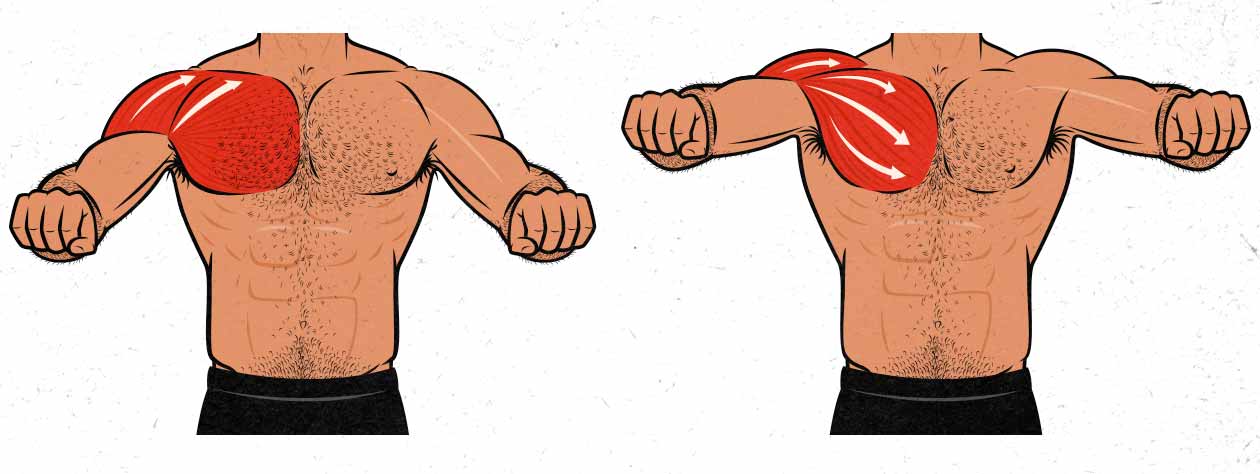

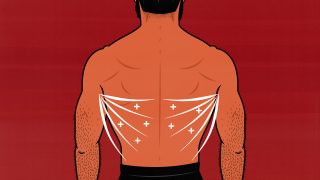

The chest fly is the most common isolation lift for the chest, and with good reason, too. Just like the bench press, it trains the chest with a deep range of motion. But unlike the bench press, the triceps aren’t engaged at all. And because the fly is done with the arms going out to the side, it mirrors the technique of the wide-grip bench press, prioritizing the chest over the shoulders:

There are a few popular variations of chest fly:

- The dumbbell fly: this is most classic chest fly variation, and it’s done with a simple pair of dumbbells. It’s hardest at the bottom of the range of motion, which raises questions about whether it’s safe on the shoulder joint and whether it has a good strength curve for building muscle.

- The machine fly: this variation of the fly is done using an exercise machine specifically designed for the chest fly. These are usually made to have a fairly flat strength curve, making it equally challenging throughout the entire range of motion.

- The cable fly: this variation of the fly is done by standing between two cable stacks. It’s often said to be the most optimal variation because it allows our chests to work freely through a full range of motion, and it allows us to get a full contraction of our pecs at the top.

At first glance, it may seem like the cable fly is the best variation, the machine fly is the next-best, and the dumbbell fly is the worst—and may even be dangerous! But a few principles of muscle growth are being overlooked.

In Defence of The Dumbbell Fly

As we’ve just covered, the dumbbell fly is very similar to the wide-grip bench press. It works the chest hard in a deep stretch. The only real difference is that it’s lighter, making it less metabolically taxing and easier to recover from, and it puts even more emphasis on our chest, making it more of an isolation lift.

Even so, the dumbbell fly is criticized for a few different reasons:

- It’s disproportionately hard at the bottom of the range of motion.

- It isn’t challenging at the top of the range of motion.

- It can be hard on our shoulder joints.

Let’s go over these purported problems one by one.

Being Hardest at the Bottom is Good

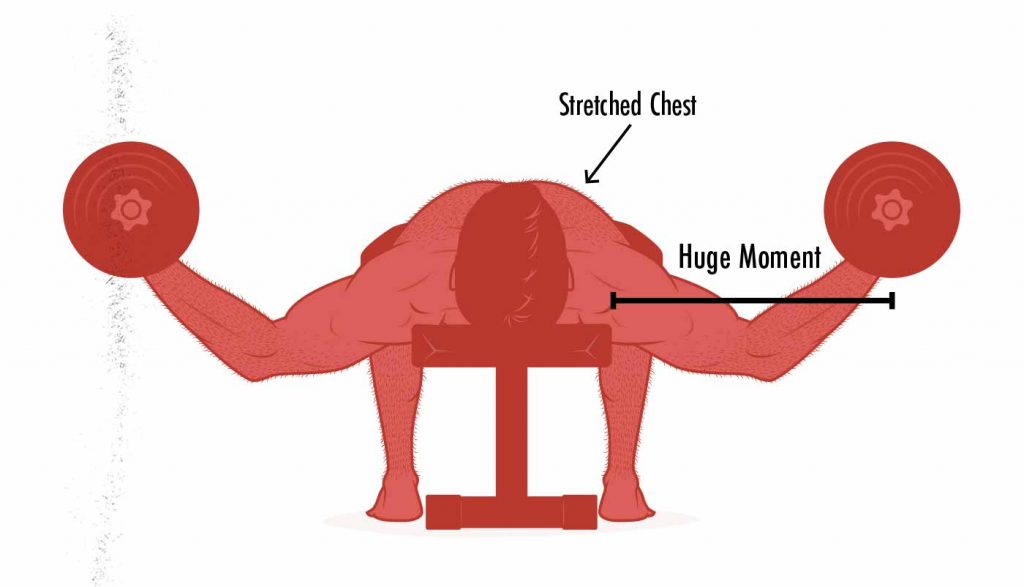

The next reason the dumbbell fly comes under fire is for being disproportionately hard at the bottom of the range of motion. And that’s entirely true. The dumbbell fly is super hard at the bottom of the range of motion.

Muscle growth is stimulated via mechanical tension—the force that tries to stretch our muscles. As we lower the dumbbells down, we create longer moment arms at our shoulder joints, making the lift much harder. This is called active tension. But our muscles also behave kind of like elastics. When we stretch them, they pull back towards their natural resting length. This is called passive tension. Both are important.

What happens in the dumbbell fly is that as our muscles stretch longer, we need to actively exert more force. The bottom of the fly is the hardest, and so that’s when active tension is the highest. Simply because it’s the hardest part of the lift, that’s where the most muscle growth is stimulated.

But we also need to consider the passive tension. Because our pecs are stretched out like elastics at the bottom of the fly, they’re also trying to snap back to their normal length. This makes us stronger, helping us overcome the sticking point. And it also gives us a double whammy of both active and passive mechanical tension adding together, stimulating a ton of muscle growth.

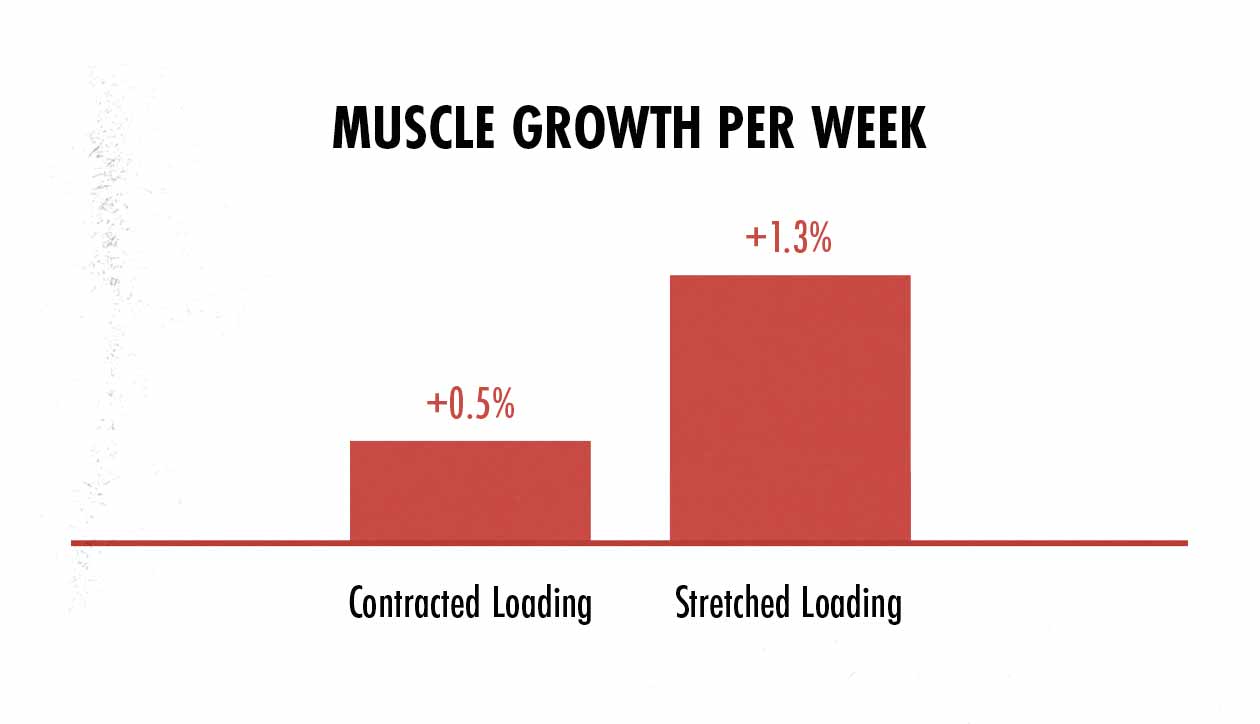

This is why lifts that are hardest when our muscles are stretched are much better for stimulating muscle growth. This mechanistic explanation bears out in the research, too:

In a recent meta-analysis, the lifts that challenged our muscles in a stretched position yielded nearly three times as much muscle growth as lifts that challenged our muscles in a contracted position. This makes the dumbbell fly perfect for building a bigger chest. (And it also explains why deep front squats are so good for our quads, deep bench presses are so good for our chests and shoulders, and deep deadlifts are so good for our glutes hamstrings.)

Lifts that are hardest at the bottom are ideal for building muscle, making the dumbbell fly a great hypertrophy lift.

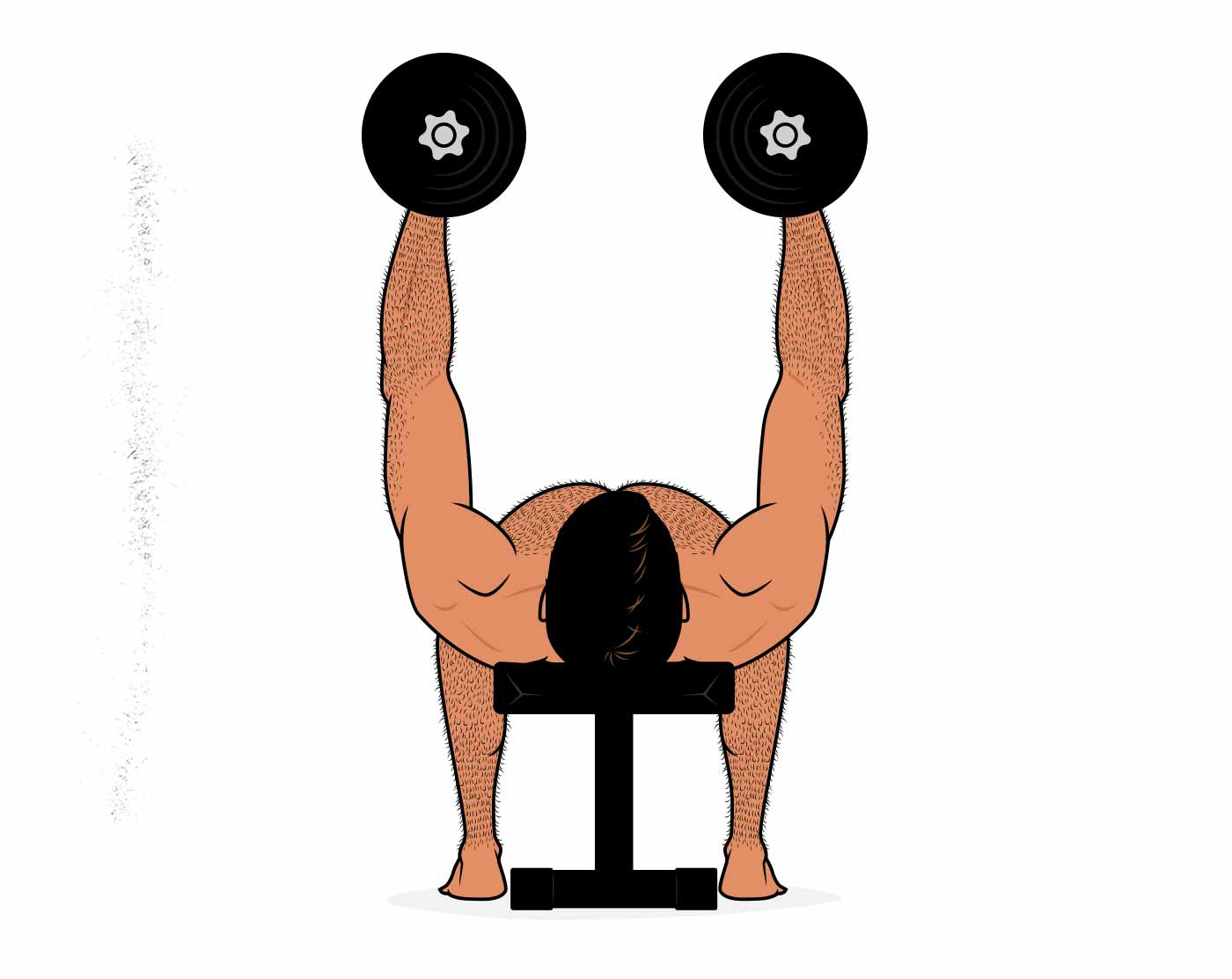

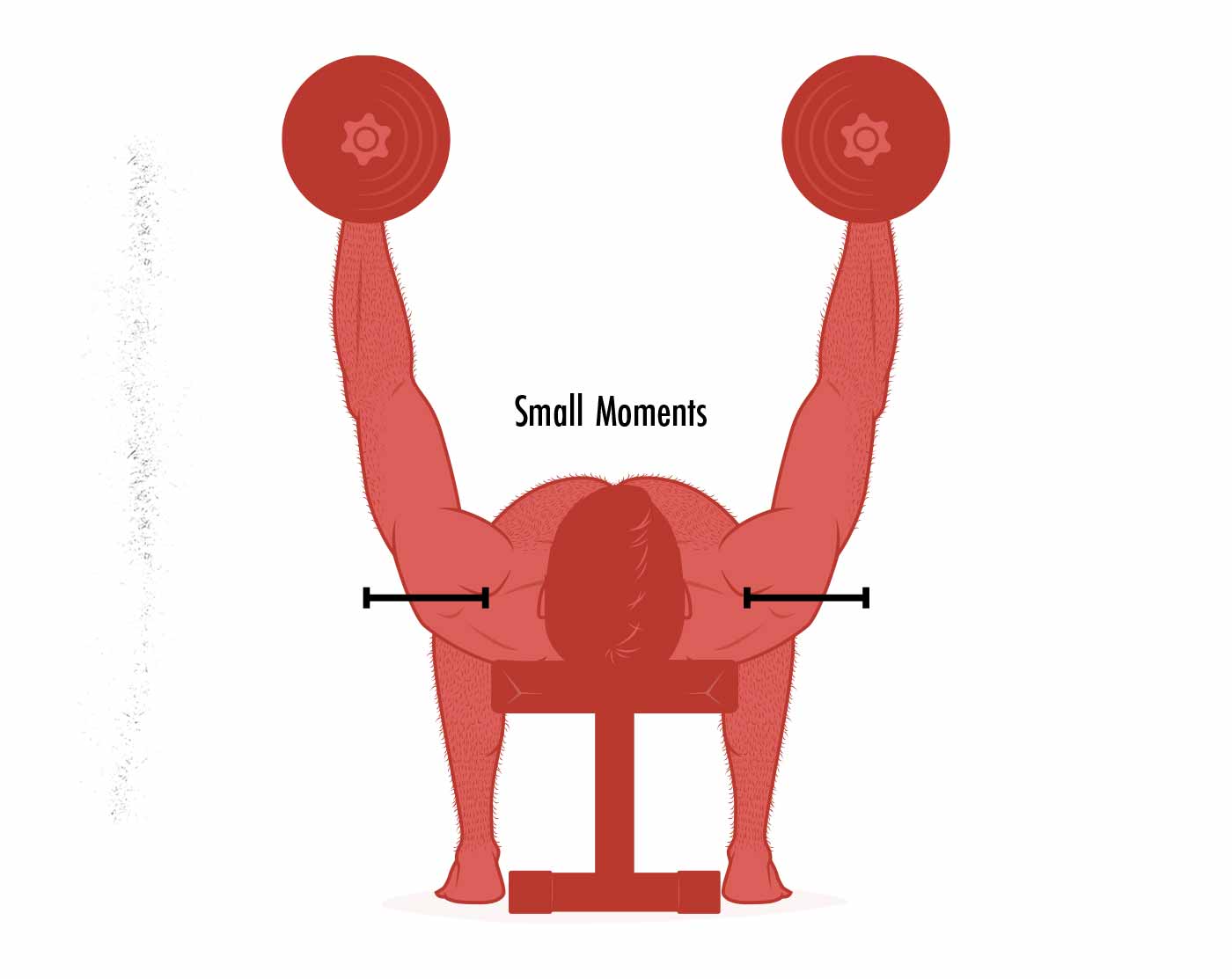

Being Easy at the Top is Okay

The next concern is that the dumbbell fly isn’t challenging enough at the very top of the range of motion, and that’s totally true. When we’re holding the dumbbells suspended above us, the moment arms completely disappear. All our chests need to do is keep them balanced. Easy.

But that’s also true of the bench press, the front squat, the deadlift, and the overhead press, all of which are amazing lifts for building muscle.

As we explained in the previous section, it’s much more important to challenge our muscles in a stretched position. That’s where all of these classic free-weight lifts shine, and that’s why they’re so incredibly good for building muscle. The dumbbell fly is no exception.

Now, would it be better if there was tension on our muscles in the contracted position? Maybe. But challenging our muscles in a contracted position doesn’t stimulate nearly as much growth. There’s no passive tension being added to the active tension, meaning overall mechanical tension is lower. And since mechanical tension is the main driver of muscle growth, not as much muscle growth is stimulated.

However, that doesn’t mean that the contracted position is useless. First of all, it will still stimulate some muscle growth if we challenge our muscles in a contracted position. And second, there’s research showing that keeping constant tension on our muscles throughout our sets can yield quite a bit more muscle growth.

So in an ideal world, we’d have a lift that maximally challenged our chests in a deep stretch (like the fly) but also kept at least a little bit of tension on our chests in the contracted position (as a cable crossover would do). Does that lift exist?

Fortunately, yes. We can keep constant tension on our pecs when doing the dumbbell fly simply by skipping the very top part of the lift, keeping small moments at our shoulder joints. Is it a perfect solution? No. But that top part of the fly doesn’t matter very much anyway, so no real harm in skipping it.

The dumbbell fly is dead easy at the top of the range of motion, but that’s okay. In fact, you can even skip the very top of the range of motion, keeping tension on your chest throughout the entire set.

Is the Dumbbell Fly Dangerous?

So, first of all, the dumbbell fly works our shoulders through a very similar range of motion as the bench press, with much lighter weights, and with our shoulders externally rotated, which tends to prevent shoulder impingement issues. The bench press is quite a safe lift (when done correctly), and the dumbbell fly is likely even safer (again, when done correctly). There’s no reason to think that you’re making a deal with the Devil, sending your shoulders to Hell in exchange for a bigger chest.

Now, with that said, the dumbbell fly can be dangerous when performed recklessly (as is true with almost any lift). If we choose a weight we can’t manage properly, we lift in low rep ranges, and we drop too quickly into the bottom position, the dumbbell fly can stress our shoulder joints, causing inflammation or injury. But if we do the dumbbell fly carefully, it’s really quite safe. The lesson isn’t to fear the dumbbell fly, just to lift with sensible technique (as you should be doing anyway).

To reduce the risk of injury, it can help to use appropriate rep ranges (10–20 reps per set), lift with proper technique (slightly bent elbows), lower the weight down fairly slowly (2–4 seconds), and maintain good control throughout the full range of motion. For instance, instead of bouncing the weight off of your shoulder joints at the bottom of the fly, slow the weight down with your muscles.

Speaking of which, that’s a good rule of thumb for most other hypertrophy lifts, too. Instead of letting the weight rest on our joints at the bottom of the range of motion, we want to keep the tension on our muscles. Not only will that prevent our lifts from beating up our joints, it will also help us build more muscle.

Finally, when doing the dumbbell fly, we can use a technique that’s similar to our bench press, tucking our shoulder blades and getting a bit of an arch in our backs. Not only will that keep our shoulders a bit safer, but it will also allow us to get an even deeper stretch on our chests.

To keep the dumbbell fly safe, it’s best to lift in moderate-to-high rep ranges (10–20 reps per set), lower the weight downs slowly, keep the tension on your muscles instead of resting it on your shoulder joints, and avoid lifting past the point of technical failure.

Is the Cable Fly Better?

The dumbbell fly, although often maligned, is a great lift for building a bigger chest. But that doesn’t tell us how it compares to the cable fly. If the cable fly keeps tension on our chest all through the range of motion, does that make it even better for building muscle?

So, first of all, there’s a bit of an incorrect assumption here. As a general rule of thumb, free weights tend to stimulate at least as much growth as machines and cables. There’s a reason why free weights are the default tool for hypertrophy training.

The dumbbell fly also has a long and illustrious history as the favoured chest isolation lift. It’s been used by bodybuilders for several decades now with much success. We need to be wary when replacing a tried and true lift with a trendy one.

Even so, it’s certainly possible that the cable fly is better at stimulating chest growth. But it’s quite unlikely, and let’s talk about why.

The cable fly is done by standing between two cable stacks. This makes the beginning of the range of motion a little bit easier, which is bad. The best opportunity to trigger muscle growth is when our chest is stretched. That’s when we have both active and passive tension combining together to boost overall mechanical tension on our chest. If that part of the lift is easier, there isn’t as much mechanical tension, and the lift won’t stimulate as much muscle growth.

But on the plus side, the cable fly is quite hard when our chests are in a fully contracted position. In fact, some people even cross their hands over one another to extend the range of motion even further (a cable crossover). But challenging our muscles in a contracted position isn’t very good for stimulating muscle growth. The constant tension can be good, yes, but we can do that just as easily with the dumbbell fly (simply by cutting the range of motion a bit short).

So what the cable fly is doing is making the lift easier where it should be harder, and harder where it should be easier. It’s the same problem that resistance bands have. The strength curve isn’t very good for building muscle.

Now, just to be totally clear, none of this means that the cable fly is a bad exercise for bulking up our chests. It’s not. It’s a fine lift. But it’s probably not as good as the dumbbell fly.

The cable fly is a perfectly fine isolation exercise for our chests, and it will indeed stimulate muscle growth. But the dumbbell fly is probably better.

What About the Machine Fly?

The machine fly has a few advantages over the cable fly. Not only is it a more stable lift than the cable fly, which tends to allow for heavier loading, but it also has a flatter strength curve. It’s not supposed to be easy at the bottom of the range of motion and nor disproportionally hard at the top. If the machine is well designed, it should be similarly challenging throughout the entire range of motion. And even if it is hardest at the top, it’s probably not dramatically harder at the top.

I’m not sure that the machine fly is significantly better or worse than the dumbbell fly. If I had to bet, I’d say that the dumbbell fly might be a tiny bit better, but it could just as easily go the other way. I don’t know.

Practically speaking, it’s quite easy to challenge our chests in a stretched position with a machine fly. So if you have access to one, I think it may be worth seeing which one allows you to get a deeper stretch, and which one is more challenging in that deep stretch.

It’s very easy to test. Try taking a set of chest flyes to failure using the chest fly machine. Where do you fail? If you fail while your chest is stretched, great. That means that the hardest part is the bottom. If you fail because your chest runs out of gas at any point in the range of motion, that’s also great. That means that the strength curve is flat. But if you always fail when your chest is in a fully contracted position, eh, not so great.

The machine fly is a good lift for chest hypertrophy, and probably better than the cable fly, but the dumbbell fly may still be the best of all. It will likely depend on the specific machine.

Should we Train Our Chests With Different Strength Curves?

The next question is whether we should train our chests with a variety of different strength curves. For example, perhaps we want to choose lifts that work our chests hardest in a stretched position as our main lifts, but then add in some extra lifts to work our chests in a contracted position. Maybe if we train our chests with a variety of different strength curves, it will lead to faster growth or full development, right?

There’s actually no good evidence that we need to train our muscles with a variety of different strength curves. Maybe with compartmentalized muscles like our abs, it could help. We could do crunches for our upper abs, hanging leg raises for our lower abs. But with our pecs, it’s the same muscle fibres being stimulated by both the dumbbell fly and the cable crossover. There’s no reason to think that cable crossovers would train our inner chests or anything along those lines.

This means that to train our inner chests, best to train our chests with a deep stretch. And if we want to train our outer chests, again, best to train our chests with a deep stretch. The dumbbell fly is perfect for that.

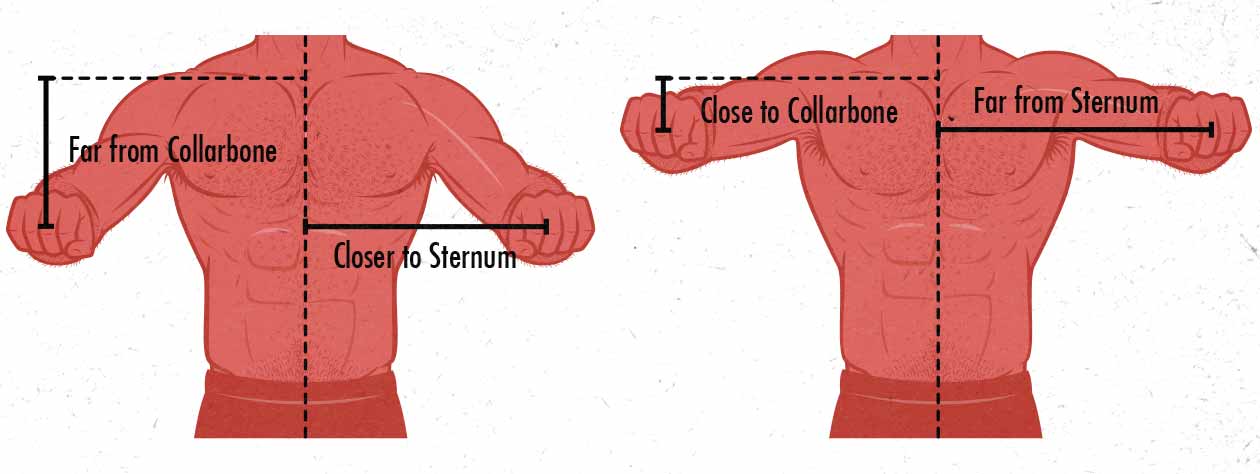

However, it can help to train our chests with a variety of different angles. For instance, if we do a close-grip bench press with tucked elbows and we touch the barbell low on our chests, it will do a great job of stimulating our upper chests and shoulders. Or, if we do a wide-grip bench press with flared elbows and we touch the barbell high on our chests, it will do a better job of stimulating the beefy muscles in our lower and mid chests.

It all comes down to the moment arms that are being created by the different bench press variations. The wide-grip bench press, like the dumbbell fly, creates longer moment arms for our sternum, training the chest. The close-grip bench press, on the other hand, creates longer moment arms for our shoulders and upper chest.

Anyway, this is all to say that instead of training our chests with different strength curves, we just need to make sure that we’re training the fibres that connect to both our sternums and collarbone. To do that, if you bench with a moderate or narrow grip, then the dumbbell fly is a perfect lift to add to your chest routine. But if you bench with a wide grip, maybe you want to think of adding in some close-grip (or incline) bench press instead. That way you’re also training your upper chest.

There’s no reason to think that we should train our chest with different strength curves. Rather, it’s better to train our chests with the best strength curve: to challenge it in a deep stretch. However, we do want to train both our lower and upper chests. For example, we could combine a close-grip bench press (to emphasize our upper chests) with a dumbbell fly (to emphasize our lower and mid chests).

Summary

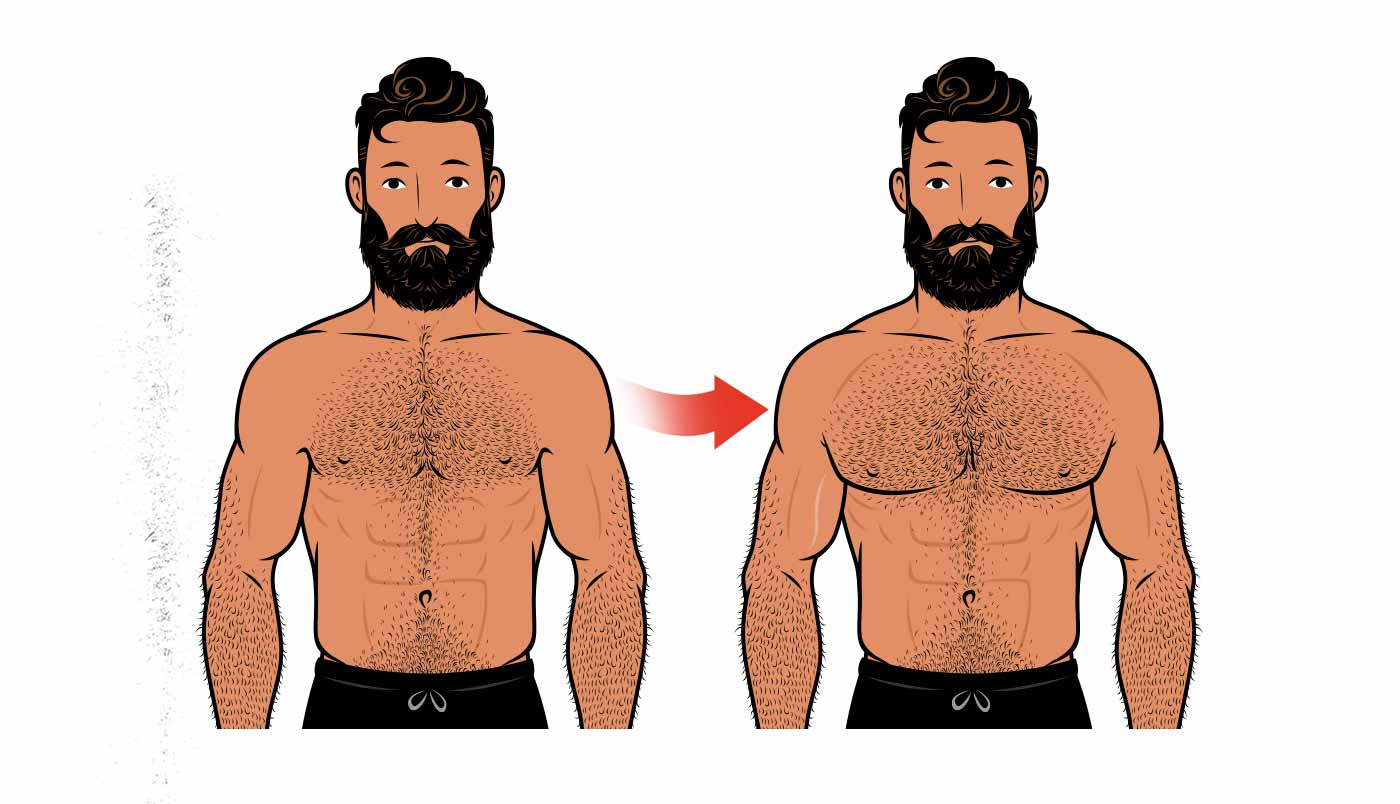

The dumbbell fly is a classic for a reason. Not only is it safe when done correctly, but it maximally challenges our pecs when they’re in a deep stretch, making it a great isolation lift for building a bigger chest. In fact, it’s probably a better variation than the cable fly, and it may even be better than the machine fly. So if all you have is a pair of dumbbells and a bench, rest assured that the dumbbell fly will serve you well.

Although to be clear, we’re nitpicking here. All three of these chest fly variations will be limited by the strength of your chest, and so all three of them will stimulate at least a little bit of muscle growth. It’s perfectly reasonable to go with your preference, especially if one of them feels awkward or hurts your shoulders.

There’s also no evidence that we need to train our chests with different strength curves. It’s probably best to simply train our chests with the best strength curve: to challenge our pecs in a deep stretch. The bench press and dumbbell fly are perfect for this, as are dips and deficit push-ups.

If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. Or, if you aren’t an intermediate lifter yet, try our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program for skinny beginners. If you liked this article, I think you’d love our full programs.

I was having this exact debate with myself this week as I consider how to program my next push day. Thanks for the article guys! Solid work as always.

Our pleasure, Nick 🙂

Thank you so much for the article!

Our pleasure, Eugene 🙂

If we add bands to the dumbbell fly do you think could optimize the strength curve? Greetings from Brazil, learning a Lot with those articles!

Hey Waldir, greetings from Mexico!

You can align the resistance curve with the strength curve by adding bands to weights, but you probably don’t need to. Most research so far hasn’t shown much benefit to accomodating resistance. I suspect that’s because the bottom part of the range of motion, where our muscles are under a deep stretch, is where most of the muscle growth comes from. Bands down increase the stimulation at the bottom, and so maybe that’s why they don’t seem to give much extra muscle stimulation.

I’m eagerly waiting for more research on accomodating resistance for hypertrophy, though. It’s theoretically possible that it could help, and I’d be interested in it if so.

I’m curious how this can be used in pulling exercises. You’re never going to get the same deep stretch when starting in a pull up, or bench row. The muscle is extended, and under tension, but it’s a fine line from being relaxed. It’s only at the top of the movement that you fail in a pull. Contraction, which is, as you write here, not the best way to build muscle. This would seem to mean there is no benefit to doing a pull up past the bar, or pulling a row all the way to your chest. No need to fully contract the muscle. right?

Hey Sabs, you’re right, yeah. The classic compound pulling exercises tend to have a worse strength curve for building muscle. Even if you use a full range of motion, the bottom parts of the lifts are disproportionately easy. That’s not ideal for building muscle.

There are some exceptions, though. T-bar row machines are heaviest at the bottom, lightest at the top. That’s the row variation with the best strength curve. They’re often chest-supported, too. So if you train at a gym that has one, you’ve got a great rowing option.

Pullovers, straight-arm pulldowns/lat prayers are hardest when the lats are under a deep stretch. They’re a great accessory lift for loading your lats under a deep stretch. They don’t tend to be as heavy, though. You’d probably be doing them after doing a bigger lift like a chin-up.

The other thing to keep in mind is that loading your muscles under stretch is just one factor. It’s an important factor, and it’s worth optimizing when you can, but you can still build tons of muscle with regular chin-ups and rows. That’s how most people build big backs.

It’s not that there’s NO benefit to getting a full contraction at the top of rows and chin-ups. It’s just that it’s the least important part of the range of motion. What you could do is pull all the way to your torso during the first few reps, when you’re strong enough for it. But then continue doing reps even after you can’t bring the weight all the way to the top. That’s technically taking the set past failure, but there’s fairly little downside to doing it (especially on your final sets). That will give your muscles a bit more work at longer lengths.

Just do a step forward at the cable machine and you have the same stretch. Weird article imo.

That’s a perfectly good way to train your chest. The dumbbell fly would still bias the bottom of the range of motion more, though. It’s also more stable and easier to set up. I still prefer the fly. But if you prefer cables, that’s totally fine. Both are great.

fenznybkzsyqghpzqnfmzysfbpvwjq

cyradpwtsecbmeowzysnfusvakexvx