The Barbell Buyer’s Guide (for Bodybuilding & Hypertrophy Training)

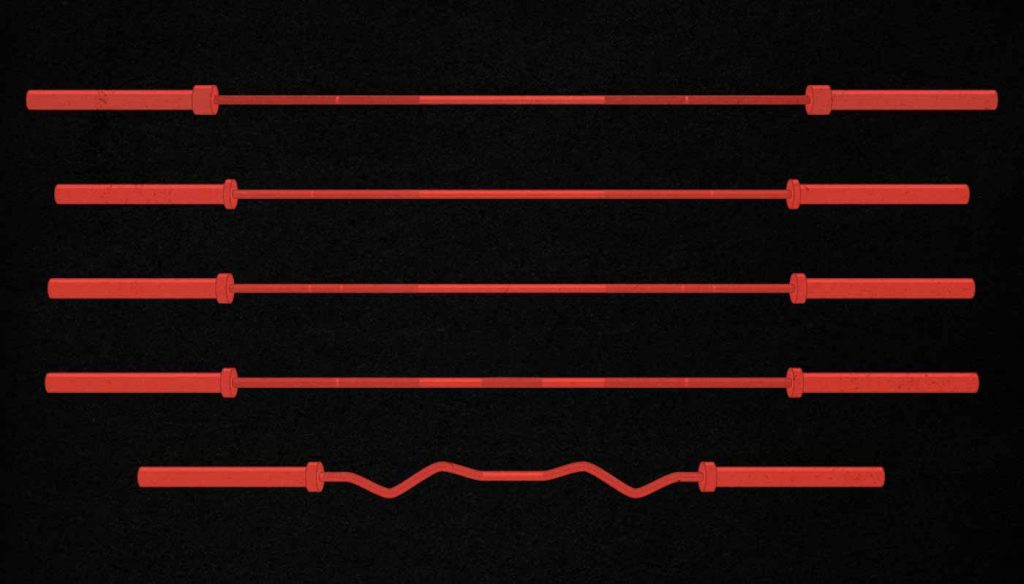

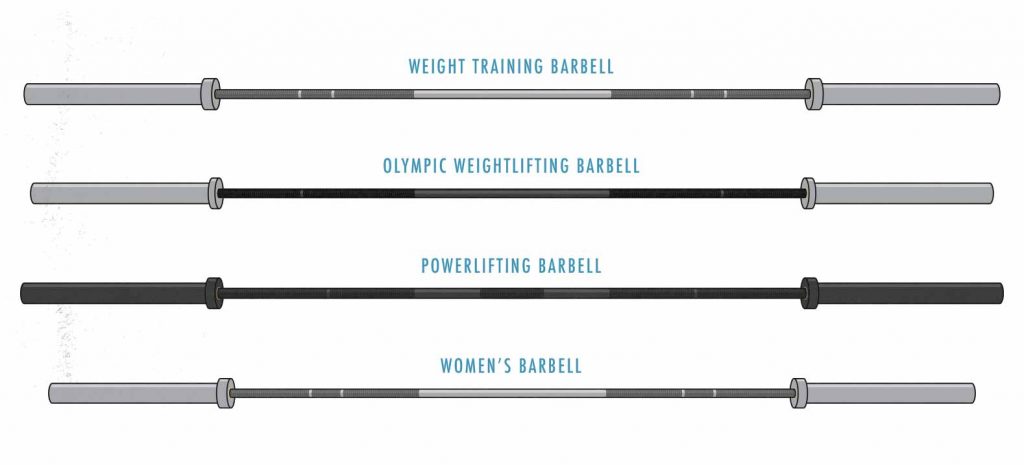

While writing our guide on how to build a barbell home gym, I dove way too deep into researching barbells. Which companies make the best barbells, which coatings do the best job of preventing rust, which type of knurling is best, and so on. Perhaps more importantly, there are several different types of barbell, all of which look fairly similar, but all of which are designed for different styles of lifting:

- Olympic weightlifting barbells are smooth, thin, and springy, designed to be tossed and dropped. This makes them great for Olympic weightlifting and CrossFit, but a poor choice for building muscle and gaining strength.

- Strength training “power” barbells are rough, hard, and thick, designed for heavy and methodical lifting.

- Multipurpose barbells are a mix of the two. They’re smooth and springy enough to catch on our shoulders but have enough grip and stiffness to use for strength training.

Most people assume that multipurpose barbells are designed for general strength training and bodybuilding, but that’s actually not the case. They’re designed for powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting—for programs like Starting Strength, which includes both the low-bar back squat (a powerlifting lift) and the power clean (an Olympic lift). It’s a barbell designed for two very specialized types of lifting.

If we’re lifting weights to gain muscle size and strength, or to improve our health and appearance, then we aren’t going to be doing Olympic weightlifting or powerlifting. And if we aren’t doing either of those styles of lifting, we sure don’t need a barbell designed for both.

So what type of barbell should we buy?

What’s A Barbell?

Barbells are long metal bars that you can attach weights to. They’re used for strength training, bodybuilding, hypertrophy training, CrossFit, and Olympic weightlifting. They like this:

Barbells are so valuable because we can vary the weight from exercise to exercise and increase the weight gradually from workout to workout. One week, you lift the 45-pound bar. The next week, you add 2.5-pound plates to either side. Now you’re lifting 50 pounds. Then 55. That’s how, over time, you build muscle and get stronger. This principle is called progressive overload.

You can gain muscle and strength with a wide variety of implements, of course, ranging from resistance bands to dumbbells to exercise machines to bodyweight training. All of those can work, and all have their own unique advantages. Still, barbell training tends to be the easiest and most efficient way to gain muscle and strength. Here’s why:

- Barbell resistance curves lifts mimic the natural strength curves of our muscles. The reason for this is simple: we evolved to lift heavy things against gravity, not to use exercise machines or resistance bands. Barbells are perfect for this. They allow us to challenge our muscles where they’re strongest, stimulating more muscle growth with every repetition.

- Barbells can be loaded heavy, meaning that we can choose bigger compound lifts, engaging more overall muscle mass with our lifts. It’s also impossible to outgrow them. We won’t ever be able to lift more than the thousand pounds a barbell can hold. Especially not for several repetitions.

- Barbells can be made heavier in itty bitty increments, allowing us to add just a couple of pounds to our lifts every workout. This makes it easier to achieve progressive overload.

- Barbell training is simple and efficient. You can choose a few compound lifts, a few isolation lifts, and you can focus on gradually getting stronger at them. It’s not finicky or convoluted.

As a result, people who are serious about lifting weights, building muscle, and getting strong will usually build their training routines around the big barbell lifts. They might still do some push-ups and chin-ups or do some leg pressing after their squats, but their routines are built on a foundation of barbell strength.

Barbell Training for Muscle Size & Strength

When we’re thinking about barbells, we aren’t coming at this from the perspective of Olympic weightlifters or powerlifters, both of which are sports that have their own unique requirements. We’ll cover the details of those barbells, as well as the pros and cons of those styles of training, but we’re assuming that you’re looking for a barbell that will help you build muscle, gain general strength, become more fit, and improve your appearance.

Now, just to clear up any potential confusion, when people are talking about lifting, sometimes they’ll call the big barbell lifts “strength training” and they’ll call training for muscle growth “bodybuilding,” but those can have their own nuances to them:

- Bodybuilding can simply mean building muscle, but it can also mean training primarily for aesthetics, cutting down to obscenely low body-fat percentages, and then stepping on stage. Bodybuilding is a sport with its own culture.

- Strength training can simply mean training to become bigger and stronger, but it can also refer to the type of training that powerlifters do, where it’s all about improving maximal strength on the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Again, strength training has its own unique culture.

- Hypertrophy training is simply training to become bigger, stronger, healthier, and better looking in whatever way is most effective. Some people might call it bodybuilding or strength training, but it’s more synonymous with bulking, and it doesn’t carry any baggage.

Before we talk about the nuances of the different barbells, it helps to know what kind of lifting best matches our goals. Then we can buy the barbell that perfectly matches that style of lifting.

If we design our workout program to help us gain both size and strength, our training will have quite a lot in common with regular strength training. We might choose front squats instead of low-bar back squats, we might bench with a narrower grip, and we might favour conventional deadlifts over sumo deadlifts, but our lifting routines are still built around the big compound lifts. In fact, we actually want to add two more big compound lifts to the mix: chin-ups for our backs and biceps, and overhead pressing for our shoulders, upper chests, and triceps. So instead of the “Big Three” powerlifting lifts, we wind up with the “Big Five” hypertrophy lifts:

These five lifts engage the most muscle mass, allow us to lift the heaviest, and allow us to build a tremendous amount of muscle with every set. They also cover all of the major movement patterns, giving us strong, proportional physiques that look great.

The next thing we need to do is bump our rep ranges higher. Most strength training is done in the 1–5 repetition range, which is great for learning how to generate more force, but not quite ideal for building muscle mass or improving our general fitness. To build more muscle, a greater work capacity, and better cardiovascular fitness, we can focus on sets of 5–15 reps per set for our main lifts, going as high as twenty or even thirty reps for our assistance lifts.

Speaking of assistance lifts, if we’re trying to become bigger and better looking, we don’t just want to be doing the big compound lifts. At the very least, we can add in some barbell rows, biceps curls, and triceps extensions. We can do all of that with a standard barbell, but we might want to look into getting a second barbell as well, such as a curl-bar.

The thing to note here, though, isn’t that we’re choosing slightly different lifts or lifting in slightly higher rep ranges, the thing to notice is that we’re choosing lifts that are done fairly slowly and deliberately. We aren’t throwing, catching, or dropping the barbell. We’re also doing lifts that can be loaded fairly heavy. That’s going to influence what type of barbell we choose.

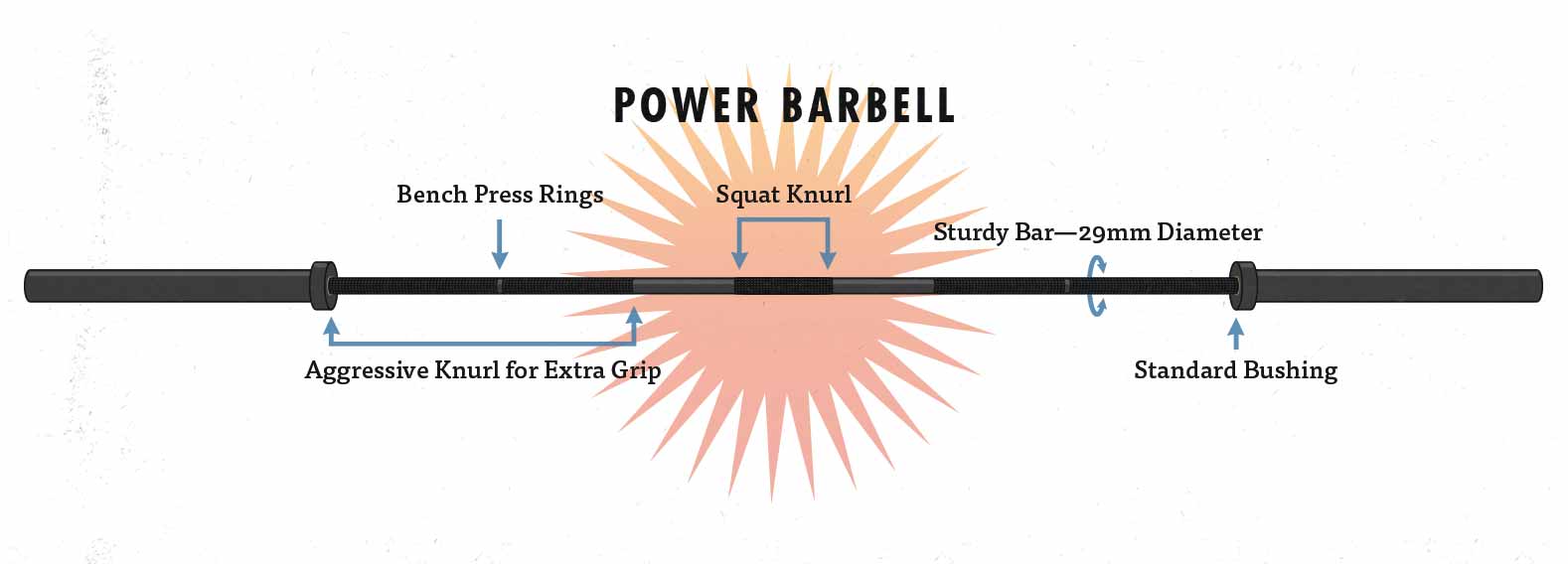

Barbell Anatomy

Cheap “Standard” Barbells

My very first barbell was a standard old barbell that I found on the side of the road. It weighed around thirteen pounds, and it was rusty and hard to grip. The weight plates fit poorly and rattled around, and if I moved the barbell too quickly, it would spin out of my hands.

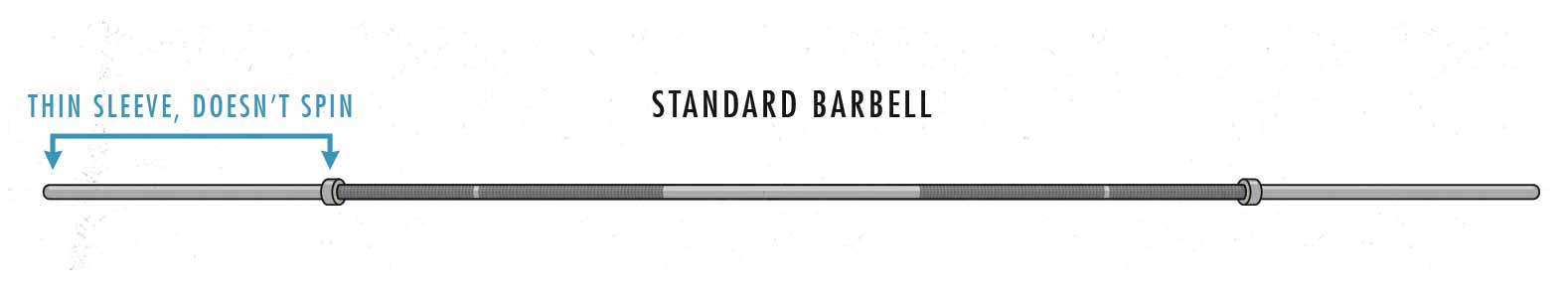

The simple one-inch sleeve on a standard barbell doesn’t rotate around the barbell, which meant that any movement of the plates would knock me off balance. This can make even light weights feel unwieldy. Still, it was the only barbell I had, and it wound up doing its job—I gained twenty pounds over the course of four months. If that sounds crazy, it was, but keep in mind that I was underweight (130 pounds at 6’2) and that this was my first time successfully gaining weight. I was taking advantage of “newbie gains.”

The point I’m trying to make here is that these barbells suck. Hard. But as the hypertrophy researcher Brad Schoenfeld, PhD, says, “Load is load.” If we have something heavy to lift, and if we can gradually make it heavier as we grow stronger, then we can build muscle.

Even with the very crummiest of barbells, we can build an impressive amount of muscle mass. But if you have the opportunity to get a nice one, boy, can it ever make lifting more fun.

Revolving “Olympic” Barbells

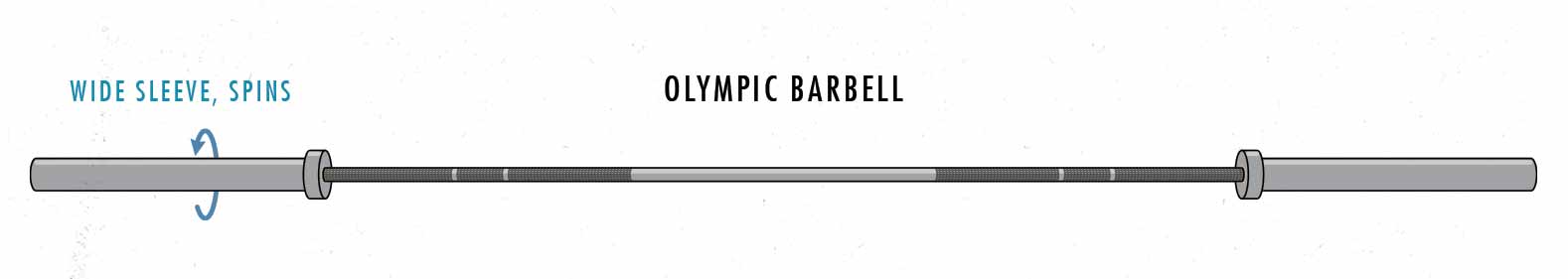

After gaining my first twenty pounds, I decided that I wanted to gain another twenty pounds of muscle. I had grown too strong for my makeshift home gym, and so I decided to start lifting at a commercial gym. The barbells there were a good foot longer, they weighed a full 45 pounds (twenty kilos), and the spinning sleeves allowed the weight plates to revolve freely, like so:

These barbells with the two-inch revolving sleeves are often called “Olympic” barbells, but that’s a bit of a misnomer. They were initially designed for Olympic weightlifters, true, but powerlifting barbells, deadlift barbells, squat barbells, and multipurpose barbells all have these same revolving sleeves. In fact, every good barbell has a revolving sleeve—even barbells designed for biceps curls.

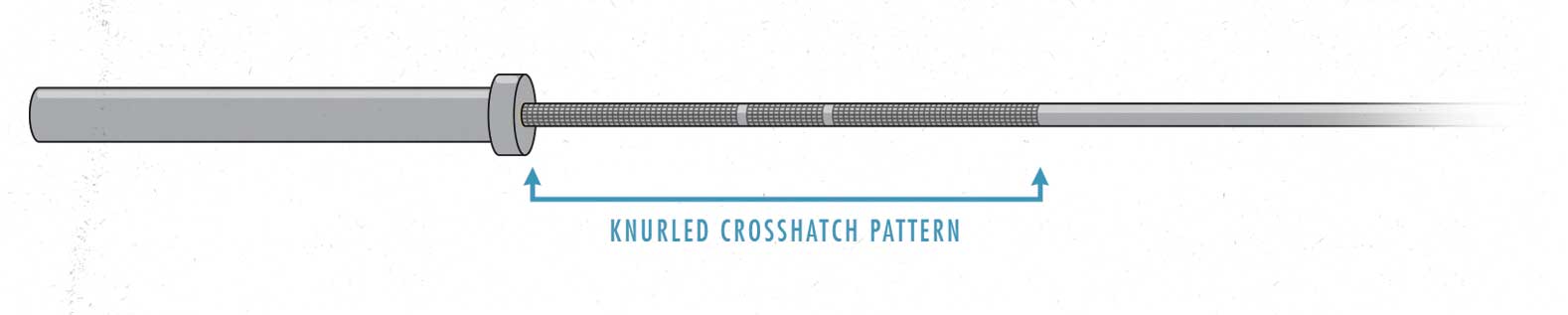

Back when I was training at home, my lifts were never all that heavy, and so I never needed to worry about how firmly I could grip it. But as my deadlifts got heavier, my grip started to slip, and I started paying more attention to the knurling—the crosshatch pattern engraved into the bar.

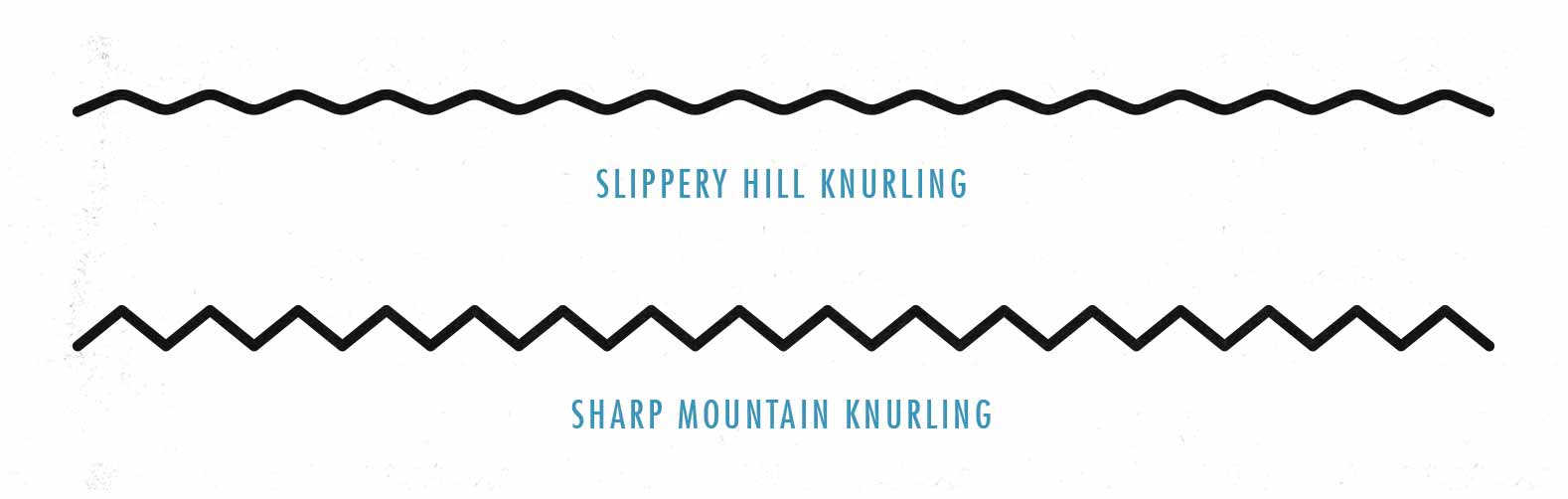

This gym had just the one type of barbell—a general-purpose barbell that was designed to be halfway decent for every type of lifting. However, some of them had mild knurling that made them slip right out of my hands, whereas others had stronger knurling that dug into my hands, enhancing my grip and toughening up my calluses.

Barbell Knurling & Grip Strength

Most gyms favour the gentler knurling because fewer members complain about their hands hurting. It only takes a couple of weeks for our hands to adapt to a rougher knurl, but many gym members fall off the wagon rather quickly, and so gym owners often pick a barbell that’s better for total beginners who come to do curls, worse for more serious lifters who come to do deadlifts.

Anyway, within around two years, I had gained 55 pounds and more than quadrupled my strength. I wanted to continue getting stronger, and I wanted to build a barbell home gym. I carefully did my research over the course of a couple of weeks, trying to find the perfect barbell for strength training.

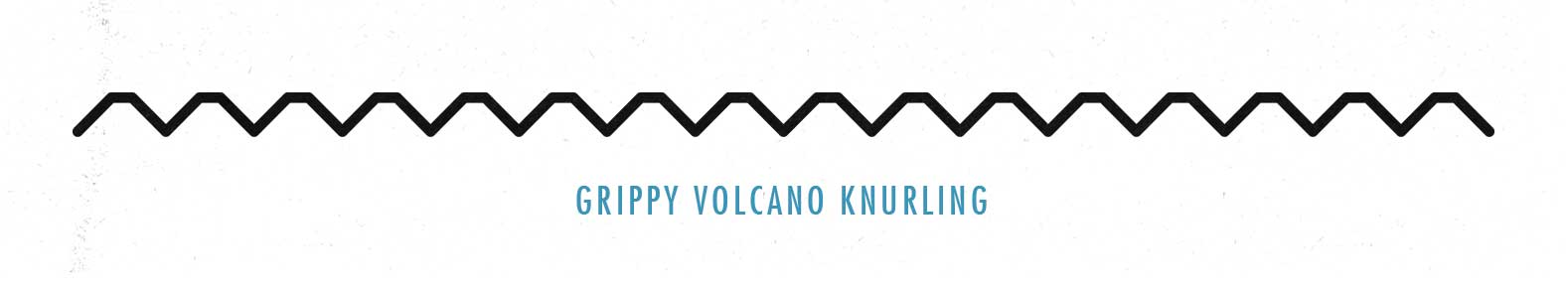

I learned that some companies trim off the pointed tips of the “mountains” to create “volcano knurling.” This increases friction by adding more points for our grip to cling to, and it also makes the knurling gentler because the points aren’t stabbing into our palms. This volcano knurling is a godsend when doing heavy deadlifts, but it’s also a great feature for really any lift.

Barbell Warping & Brittleness

When we’re buying a barbell, we want one that’s stronger than we are. We want to be able to lift as hard and heavy as we can without worrying about it breaking in two or, more likely, bending itself out of shape.

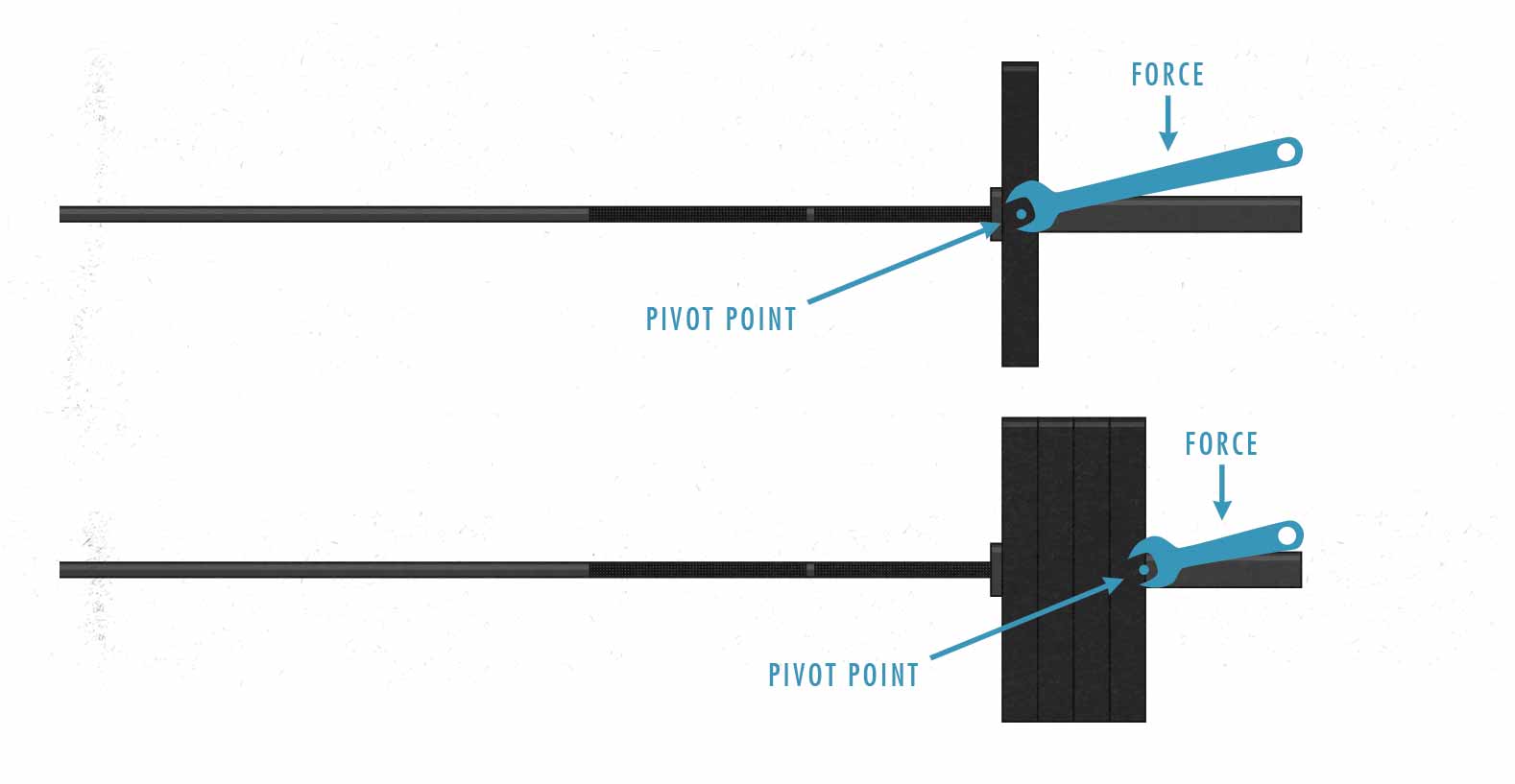

The reason most barbells get bent is that people drop them from overhead too many times with light weights on them. Now, I know that can sound a bit weird. Why would lighter weights make a barbell more likely to warp? You’d think that heavier weights would create the problem, right? But no, the weight plates land on the ground, which his perfectly fine for the barbell. It’s the sleeves of the barbell that create the torque. The less weight that’s on the bar, the more sleeve is exposed, and so the more torque there is:

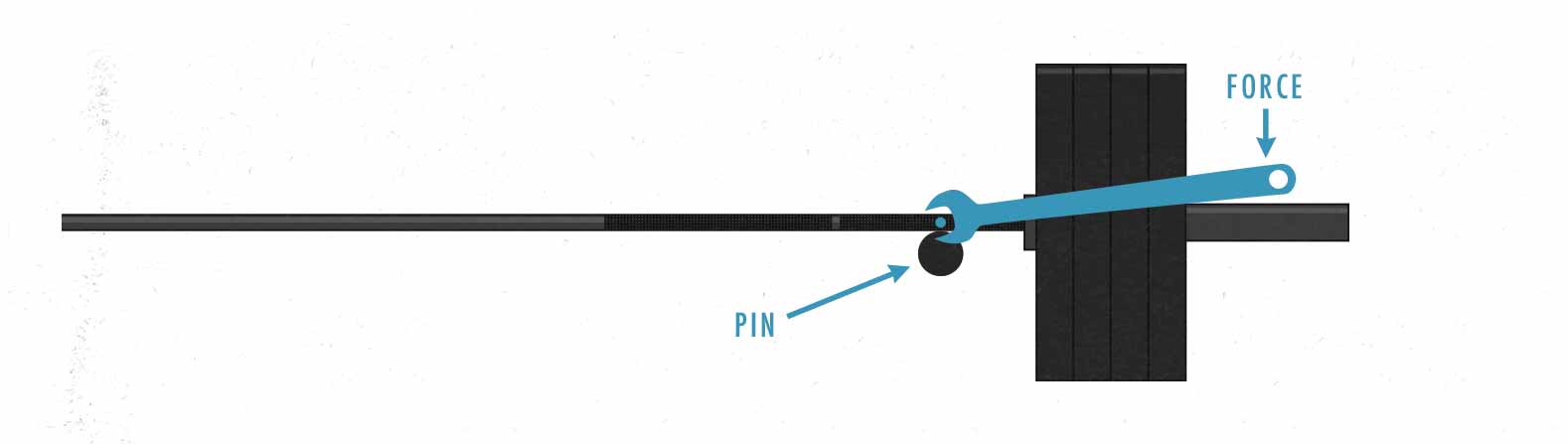

To see why that is, imagine a wrench cranking the barbell. The lighter the load, the longer the wrench, and the greater the torque. This means that dropping a barbell from overhead is fine if the weights are heavy and you only do it for a few repetitions, as is common with Olympic weightlifting. The problem is with CrossFit, which tends to prescribe higher repetitions with lighter weights.

There’s another way to bend a barbell, though, and that’s by dropping a heavy barbell on pins. In that case, the moment arms are the same regardless of the load on the bar, and so the heavier the load, the harder it will crank the wrench, and the more damage it will cause:

That means dumping a heavy lift onto the safety pins can be murder on a barbell. This happens if we fail a lift and dump the barbell, and it happens if we’re too rough with pin squats or pin presses. Most of all, though, it happens when we do rack pulls and drop the barbell down between reps. There’s nothing wrong with rack pulls, but it’s best to lower the weight down slowly every rep. Not only will our barbell appreciate, but we’ll build more muscle because of it.

But anyway, the point of this section is talk about which barbells are the most durable. Which barbells weather these injustices the best?

- We could make the barbell thicker, which is a perfect solution if we’re doing strength or hypertrophy training, but it doesn’t solve the CrossFit problem. If we’re doing Olympic lifting, we need a barbell that can flex when it lands on our joints, buffering the impact. The barbell needs to be thin.

- We could make the barbell harder, which is another great solution for strength and hypertrophy training, but it still fails to help the CrossFitters. A harder barbell is less likely to get bent out of shape, but it’s also more likely to break. Better to drop rubber than crystal, right? So again, if we’ll be dropping the barbell, it can’t be too hard.

So the takeaway here is that for doing the big compound lifts—the squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press, and so on—we can choose barbells that are thicker and harder. There’s no real cost to it. But if we’ll be using our barbells for CrossFit, we need to take a different approach.

Rogue is famous for making barbells for CrossFit, and so both their Olympic barbells and multipurpose barbells are designed to be just thin enough, just flexible enough, and just hard enough. They’re really playing it close to the edge, and they do an amazing job of it. But if you aren’t planning on doing CrossFit or Olympic lifting, you can choose a barbell that doesn’t need to make any of those tradeoffs. You can choose a barbell that’s quite a bit thicker and harder, driving the durability through the roof.

For example, Chris Duffin, over at Kabuki Strength is known for making the hardest barbells on the market (250k PSI and a Rockwell hardness of 51 RC). If we bump that barbell into anything, the barbell will win. Duffin even has a video of his barbell’s knurling grinding through other barbells. Rogue’s Ohio Power Bar is similarly famous for being able to survive anything. But to be honest, because of how thick and hard strength training barbells are, and because our style of lifting is fairly benign to begin with, we’re very unlikely to bend or break our barbells.

What’s far more likely to kill our barbells is corrosion.

Barbell Material, Coatings & Rust

Barbells are made out of steel, which is an incredibly strong material that’s quite vulnerable to corrosion. As a result, most barbells are eaten away by rust long before they ever warp or break. Knowing how humid the air is here in Cancun, I started to worry about my barbell quickly turning into a pile of rust and blowing away in the ocean breeze.

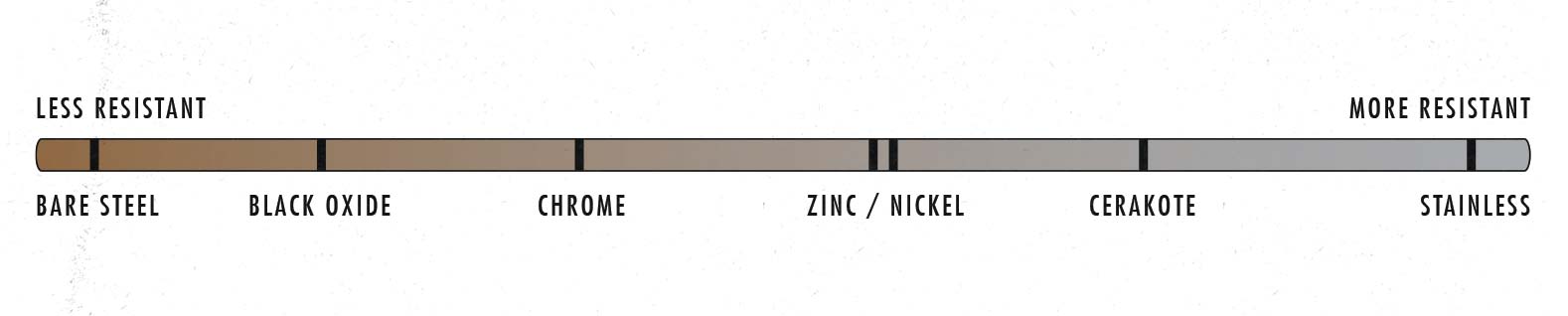

Fortunately, most high-end barbells come with either a protective finish (such as black oxide), plating (such as zinc or chrome), or are made out of steel with higher rust resistance (such as stainless steel). Each of these options offers a different degree of protection against corrosion:

You’ve got a few good options:

- Bare Steel: there’s a cadre of hardcore lifters, including Mark Rippetoe (author of Starting Strength), who believe that bare steel is superior. They don’t want the coating or plating to interfere with the knurling. Yes, their barbells begin to rust within days, but they find beauty in that rusty patina. Yes, they have to scrape all the rust away every month, but what hardcore lifter doesn’t like a little quiet time with their barbell? The problem is that every time we scrape the rust away, we’re scraping away some of the knurling. That’s how we wind up with the terrible “hill” knurling that’s so common in commercial gyms—it’s been scraped away to nothing.

- Black oxide: back in yonder years, knights would “blue” their armour to protect it from rust. People like using that same approach with barbells because it feels like steel (because it is steel). It’s not the best type of protection, but it’s enough to help our barbells survive in a climate-controlled home gym. The black oxide treatment will gradually wear away in the areas where you come into contact with the barbell, though, so don’t buy it expecting it to look new forever.

- Bright zinc: zinc barbells are far more resilient than black oxide barbells, making them a better choice for people lifting in garage gyms. However, zinc is a plating applied on top of the steel, meaning that it changes how the barbell feels. The better companies are still able to produce a good zinc knurl, but some people prefer the feel of steel.

- Black zinc: black zinc is another layer of plating that’s added on top of the bright zinc, making black zinc barbells about twice as resilient as bright zinc barbells. However, similar to black oxide barbells, the black zinc plating will gradually wear thinner as the bar ages, revealing the bright zinc underneath. It’s a durable bar, but it won’t look new forever.

- Nickel: Chris Duffin from Kabuki Strength brought nickel from the aerospace industry into the barbell industry, creating the hardest barbells ever made. This allows the barbell to bang into the rack without sustaining any wear and tear. This is the most high-end option on the market right now.

- Cerakote. Cerakote is a recent invention developed by the firearm industry to protect guns against rust. People love it because it gives near-perfect rust resistance, it gives the barbell a matte finish, and it comes in a wide variety of colours. However, although the coating is tough, it can chip off with metal-on-metal contact, especially when loading cheap cast-iron weight plates onto the sleeves. Perhaps the biggest disadvantage to cerakote, though, is that it’s applied like paint on top of the barbell, changing the feel of the knurling.

- Stainless steel. This brings us full circle, back to uncoated steel. Unlike bare steel barbells, though, stainless steel has corrosion resistance built-in, making them far more durable. The main downside to stainless steel tends to be the price. No fun colours, either.

Which barbell coating should you pick? Most serious lifters will tell you to get a stainless steel barbell and treasure it forever, passing it down to your children. I think that’s wise advice. However, zinc is the most popular choice for home gyms because of how durable and effective it is at much cheaper prices.

The Four Main Types of Barbells

There are three main types of barbells, each designed for a different style of lifting:

- Multipurpose “weight training” barbells

- Olympic weightlifting “oly” barbells

- Strength training “power” barbells

In addition to those, there are also the 33-pound (15-kilo) women’s barbells, designed for shorter, lighter people with smaller hands. They come in several varieties as well, but most of the women’s barbells are the general “weight training” barbells (which is fine).

Then there are specialty barbells, such as curl bars, safety bars, trap bars, cambered bars, deadift barbells, and squat barbells. But those make for poor primary barbells. Those would be barbells that you’d get in addition to your main barbell.

So let’s start with these four main barbells, and then we’ll dive deeper into the (totally optional) specialty barbells that you might be interested in.

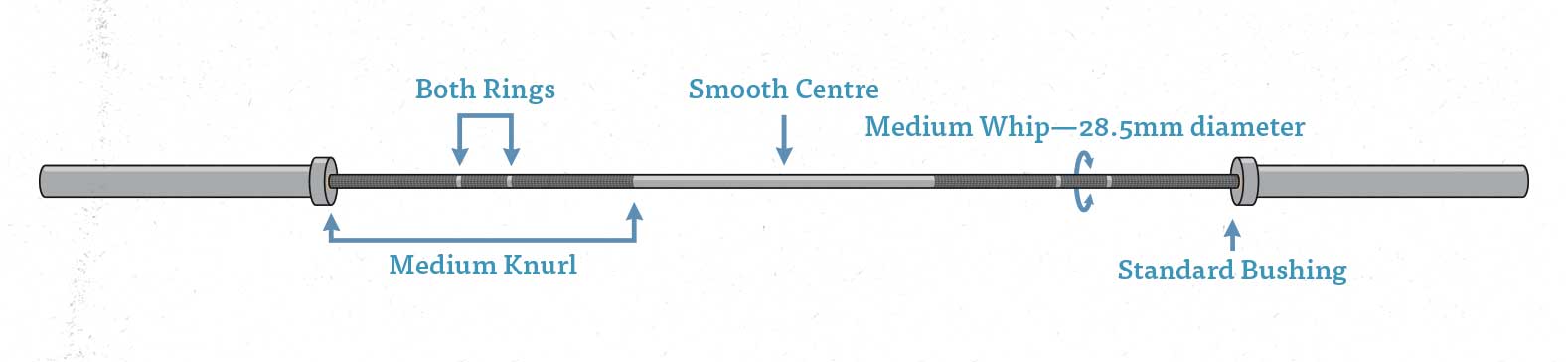

Multipurpose “Weight Training” Barbells

My assumption when I first saw the description of multipurpose barbells was that they were good for both heavy strength training as well as lighter bodybuilding, making them a great all-around bar for improving muscle size, general strength, overall fitness, and aesthetics. That’s not quite the case.

Multipurpose barbells, such as the Rogue Ohio Bar, are designed to be good for both Olympic weightlifting and strength training. These are the bars designed for programs like Starting Strength, where powerlifting lifts like low-bar back squats are programmed alongside Olympic weightlifting lifts like the power clean. They’re also a good choice for people who want to do, say, a mix of bodybuilding and CrossFit.

We’ll go into more detail below, but Olympic lifting is a style of training that helps athletes learn how to generate more power. That isn’t to say that we shouldn’t ever do it, but it’s not something that will make us bigger, stronger, look better, or improve our general health. There are far more efficient ways to do that. Olympic lifting is used more when training football and rugby players. It’s also a sport in and of itself.

If our goal is to get bigger, stronger, fitter, and better looking, we’d want something that was good for strength training and bodybuilding (hypertrophy training). These standard barbells are fine for that, but we can do even better.

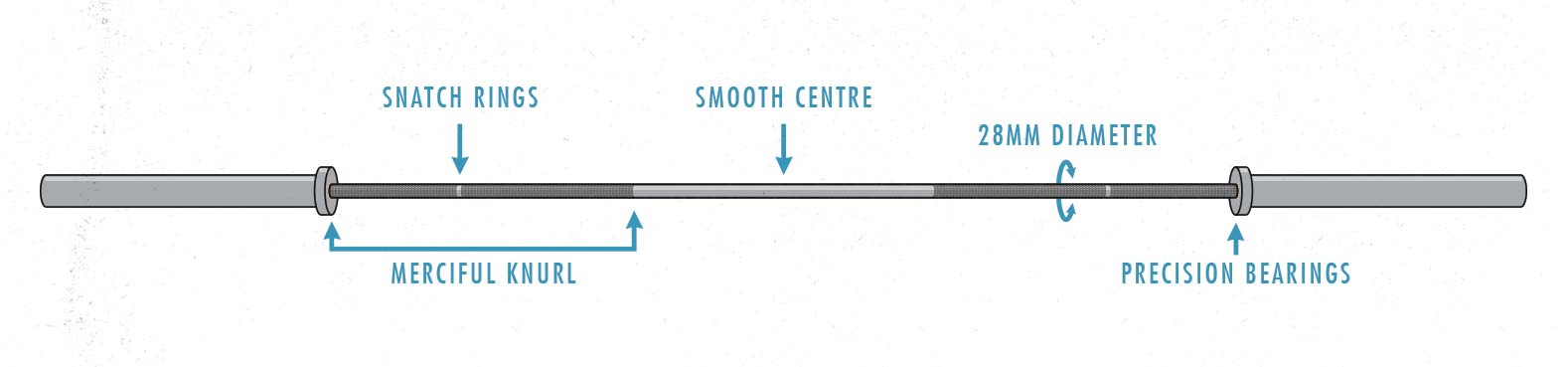

Olympic Weightlifting Barbells

Olympic weightlifting involves lifting the barbell with such incredible explosive force that it launches the barbell up into the air, at which point the athlete catches it on their shoulders or above their head.

Olympic weightlifting is an official Olympic sport, which is where it got its name. The sport is built on just two lifts: the snatch and the clean and jerk. However, it’s not just a sport, it’s also a great tool for developing general athleticism, which is why you see it in programs like Starting Strength and CrossFit.

However, Olympic weightlifting isn’t good for gaining muscle size or strength, which has made it unpopular with bodybuilders, powerlifters, strongmen, and most casual lifters. The time under tension, rep ranges, and training volume are too low to be good for building muscle or gaining strength. Plus, the weights are dropped instead of lowered, further reducing muscle growth. Because of this, even professional Olympic weightlifters tend to use lifts like the front squat for gaining muscle size and strength.

However, once we’re big and strong, the Olympic lifts can teach us to generate force more quickly—to explode into action. This makes it great for sprinters, football players, and, of course, CrossFitters. In fact, CrossFit is largely responsible for Olympic weightlifting’s recent surge in popularity.

Olympic barbells have a few key features that make them great for the sport of Olympic weightlifting and for CrossFit:

- Mild knurling: with many (but not all) Olympic barbells, the knurling is smoother to prevent it from grinding into our hands when throwing and catching the barbell. But when doing heavier lifts for more repetitions, this makes the barbell more likely to slip out of our hands.

- Smooth centre: the centre of the barbell is kept smooth so that we don’t scrape our collarbones when we catch the weight on our shoulders. This makes it better for the Olympic lifts but worse for squatting—it can slide down our torsos.

- Snatch marks: instead of having marks in the knurling to help us line up our hands for the bench press, it has marks to help us line up our grips for the snatch.

- Thinner and more flexible: Olympic barbells are thinner (28mm) than multipurpose barbells (28.5mm) and strength training barbells (29mm), making them springier and better able to absorb the shock of being thrown and caught.

- Expensive bearings: Olympic barbells use high-end bearings, such as needle bearings, to help the weight plates spin smoothly as we throw the barbell around. This makes Olympic barbells quite a bit more expensive. This is necessary for serious Olympic weightlifting but total overkill for strength and hypertrophy training.

Strength Training “Power” Barbells

Most of us want to build muscle—to become bigger and stronger. Strength training is designed for that. The lifts aren’t chosen for building muscle, the rep ranges are too low to stimulate muscle growth efficiently, and there’s too little accessory work for our shoulders, our biceps, upper backs, abs, necks, forearms, and so on. Rather, strength training is designed to help us generate more force with the muscle we already have—to become stronger for our size. Even so, there’s such a strong overlap between gaining muscle size and strength that quite a lot of muscle growth usually winds up coming along for the ride.

Still, if we design a workout program to help us gain both size and strength (like these bulking programs), we’d make some changes. We might choose front-loaded instead of low-bar back squats, we might bench with a narrower grip, and we might favour conventional deadlifts over sumo deadlifts. We’d also probably put equal emphasis on chin-ups for our backs and biceps, and overhead pressing for our shoulders and triceps, too. But regardless, all of these lifts are done smooth, heavy, and deliberate, and so they benefit from the same grippy and sturdy barbells.

So even with hypertrophy training, even though we aren’t technically doing strength training, and even though we aren’t powerlifters, we still want a barbell that’s designed for steady, heavy, and deliberate lifting. There’s no throwing or dropping. In fact, when training for muscle growth, we don’t even drop the barbell when deadlifting, and it’s rare for hypertrophy routines to have any pin pressing or pin squats.

This means that we technically still want a strength training barbell, usually known as a “power bar.” In my opinion, the best example of this is the Ohio Power Bar made by Rogue Fitness. That’s the one I bought.

These barbells look fairly standard to the untrained eye (aside from often being black), but they actually have a number of unique features that make them far better for building muscle than the barbells you’d find at the average commercial gym:

- Aggressive knurling: people often find these barbells uncomfortably rough, and your hands will feel raw for a couple of weeks as they adjust to it. But with an aggressive knurl, we won’t have the problem of the barbell slipping out of our hands when doing deadlifts and barbell rows.

- Centre knurling: strength training barbells have a strip of knurling in the middle to stop them from sliding down our torsos while squatting. But unlike a dedicated squat barbell, there are little strips of smooth so that we don’t scrape our shins while deadlifting.

- Bench press marks: the rings in the knurling mark the maximum bench press width—index fingers on the rings—that’s allowed at powerlifting meets. This doesn’t really matter with hypertrophy training, and we’ll want to use a variety of different grip widths, but it’s nice to know how wide we’re gripping the barbell.

- Extra thickness: powerlifting barbells are thicker (29mm) than Olympic weightlifting barbells (28mm) and multipurpose barbells (28.5mm). This makes them more durable, and it also stops them from wobbling around as we do our lifts. When we’re bodybuilding, better for us to do the flexing while our barbells stay rigid.

- Cheap bush bearings: when Olympic weightlifters are throwing weights around, it’s important for those weights to be able to spin freely. This prevents the momentum of the lift from throwing the lifter off balance. Powerlifters don’t care about this feature, so instead of having fancy ball bearings, these barbells have cheap bushing. That’s fine. It can trim hundreds of dollars off the cost of the barbell.

Overall, strength training “power bars” are best for both strength training (and powerlifting) and hypertrophy training (and bodybuilding). If your goal is to become bigger, stronger, fitter, and better looking, these are a great choice.

Women’s Barbells

Barbells designed for women usually weigh 33 pounds (fifteen kilos) instead of 45 pounds (twenty kilos), they’re often about half a foot shorter, and they have a thinner diameter (25mm). This makes them a little easier for smaller people to carry around and grip.

The big question here is whether women should get a regular barbell or a women’s barbell. So, first of all, these barbells aren’t ideal for women, they’re ideal for smaller people. A shorter and skinnier guy who’s new to lifting weights would benefit from these far more than a taller woman who’s already gotten quite strong.

However, most women who are still somewhat new to lifting weights will probably have at least a few lifts where they struggle to lift the bar, especially with isolation lifts like biceps curls and triceps extensions, but also lifts like the overhead press. For example, my wife is quite fit and athletic, and she can do several unassisted chin-ups, but still had trouble learning how to overhead press an empty 45-pound barbell. That issue went away after a couple of weeks, but a women’s barbell would certainly have made learning the lift easier.

Furthermore, women are on average shorter than men, and women’s barbells are designed with that average height difference in mind. If you’re used to handling a bigger barbell already, that’s no problem, but a shorter women’s barbell might be a little easier to move around.

Finally, there’s no real downside to using a women’s barbell. Most of the weight will come from the added plates, and these barbells will still comfortably hold several hundred pounds. So for someone shorter, lighter, or with smaller hands, there are some nice advantages, and there’s no real trade-off being made. May as well just get the women’s barbell.

If you’re looking for a great women’s barbell, you might like Rogue’s Bella barbell. It’s the same great quality as their other barbells, but it’s a bit shorter, lighter, and narrower.

Overall, you certainly don’t need a women’s barbell, but you very well may prefer having a barbell that’s a bit lighter and smaller. That’s especially true if you’re on the shorter or lighter side, or even if you just have small hands.

(By the way, we’ve got an entire website dedicated to helping women get bigger and stronger: Bony to Bombshell.)

Specialty Barbells

Once we have a main barbell, we really have everything we need to build as much muscle as we could possibly want. We can train every movement pattern and muscle group with a regular barbell and weight plates. We don’t need any specialty barbells.

…On the other hand, adding a specialty barbell to our arsenals can make lifting quite a bit more enjoyable. They’re a nice way to add in some extra lift variety, which can help with muscle growth. They can be easier on our joints, helping to keep us free from injury. And they can allow us to set up for two lifts at once, keeping our workouts shorter, denser, and more cardiovascularly taxing—great for general health and lifestyle.

So are they necessary? Absolutely not. But are they fun? Hell yeah! And the most fun of all is the curl bar.

Curl Bars (aka EZ-Bars)

Curl bars (often called EZ-bars) are the shorter, lighter barbells that are bent into a funny shape. The weight can vary, but they usually weigh around thirty pounds, allowing for lighter loading. The main feature, though, is that the angled grips allow us to hold the barbell with different degrees of pronation.

For instance, if we’re doing a barbell curl, we can grip the bar with our hands slightly pronated (more overhand), making the lift easier on our elbows, like so:

A regular underhand grip (full supination) can be good for the biceps, so a curl bar won’t necessarily stimulate more muscle growth, but many people find curl-bar curls easier on their joints and tendons. It can be a more comfortable way to stimulate a similar amount of growth.

Curl bars tend to be quite a bit cheaper than regular barbells, and they’re great for a variety of isolation/accessory lifts, such as:

- Barbell curls

- Reverse curls

- Overhead extensions

- Skull crushers

- Barbell pullovers

- Underhand rows

Regular barbell barbells are ideal for building up strong legs, a strong torso, and big shoulders. Curls bars, on the other hand, are all about building bigger arms. Even underhand rows are used as a way to eke more biceps growth out of our back training. For some of us, that extra arm work might not be needed. But if you’re tall, skinny, or lanky limbed—like me—then a good curl bar can be a great asset.

This makes curl bars a great second barbell, allowing us to use circuits and supersets to keep our workouts shorter, more efficient, and better for improving our cardiovascular fitness. For example, we could do a set of bench press with our main barbell, then hop over to our curl-bar for some underhand rows. Or we could do some overhead pressing with our main barbell, then superset some barbell curls.

A good curl-bar typically weighs around thirty pounds and can be loaded with standard Olympic weight plates. They have the same features as a regular barbell, too. For example, Rogue’s curl-bars have nice volcano knurling, are made of steel, and come with black zinc plating.

Curl-bars are by no means necessary. They won’t even necessarily help us gain more muscle or strength. But they can help with elbow pain, they can make our workouts more enjoyable, and they can help keep our workouts short and efficient. If you want a second barbell, I’d recommend a curl-bar.

Deadlift Barbells

The deadlift barbell, oddly enough, is almost the exact opposite of a strength training barbell. Strength training barbells are thick and designed to stay rigid under heavy loads, whereas deadlift barbells are thin and designed to flex under heavy loads.

- Strength and hypertrophy benefit from a thick bar because it keeps the barbell from wobbling. With strength training, this keeps the barbell steady when we take if off the rack. With hypertrophy training, it keeps the lifting tempo smooth and our technique consistent as we do our higher-rep sets.

- Powerlifters prefer the bar to flex when deadlifting because it creates a better strength curve, allowing them to lift more weight.

This can make it seem like if we’re interested in strength training, we’d benefit from having two separate barbells: a sturdy barbell for our squats, bench presses, and overhead presses, and a flexible barbell for our deadlifts. That’s not quite true.

A deadlift bar is designed for the sport of powerlifting, where the winner is the person who can lift the most weight for a single repetition. This means that powerlifters are always trying to improve their leverage, often by reducing their range of motion. With the deadlift, the hardest part of the lift is often the very first part—getting the barbell up to the knees. With the sumo deadlift that’s even more true. The hardest part is getting it off the floor.

If the barbell bends before the weight leaves the floor, we can open up our hip angle and drive our hips closer to the bar, improving our leverage before needing to lift the full amount of weight. If we’re pulling 500 pounds, we pull 300 pounds for the first couple inches, 400 pounds for the next couple inches, and then the barbell leaves the ground, loading us up with all 500 pounds. This is similar to using chains or bands, where the weight gets heavier the further we lift it. This creates a better strength curve: as our leverage gets better, more resistance is added. This is why the deadlift barbell is so great for deadlifting—for a single repetition.

If we’re doing a few reps in a row, the wiggly barbell makes it harder to put down and pick up the barbell the same way each time, which is unpleasant and perhaps slightly dangerous. So once we start doing deadlifts for more than a single rep, deadlift barbells become more trouble than they’re worth. If we want to min-max the strength curve, better to use bands or chains.

Deadlift barbells help powerlifters deadlift more weight, but they’re too flexible to be much good outside of that specific situation. When training for muscle mass, general strength, or general fitness, better to stick with strength training barbells.

Squat Barbells

If you’ve ever come across a barbell that seems a bit thicker and heavier than the others, that might be because it’s a squat barbell, which can run up to around 55 pounds.

When big powerlifters squat obscene amounts of weight, even the thicker strength training barbells can start to flex and wobble. Strength training barbells will hold strong under a good 500 pounds, but as a powerlifter’s numbers climb higher, that starts to change. If we’re holding a thousand pounds on our backs, even a slight bit of flex can start the barbell wobbling, and even a slight bit of wobble can be dangerous. Is that something we need to worry about? Nope. But that’s why dedicated squat barbells exist.

Squat barbells have a couple of other features, too:

- Heavier: because squat barbells are so much thicker, they also tend to weigh more. It’s common for squat barbells to weigh around 55 pounds.

- Extra centre knurling: because these barbells won’t be used for deadlifting, they won’t be gliding along our shins, and so there’s no need to leave gaps in the knurling. Squat barbells often have long strips of centre knurling to better grip our backs.

Overall, it’s neat to have a barbell that’s thicker and heavier than average, but it’s not something that the average person needs or would even benefit from. This is a specialized powerlifting barbell.

Trap Bars (aka Hex Bars)

Trap bars are the hexagonal barbells that we stand in the middle of, they have a number of significant advantages, and they’re a really interesting barbell for hypertrophy training:

- Free knee and ankle movement: when deadlifting with a standard barbell, we need to keep our shins behind the barbell and drive our hips backwards. With a trap bar, we don’t have that limitation, and we can get more bend in our ankles and knees. Bending more in the ankles and knees turns the trap-bar deadlift into more of a squat, which is both good and bad. However, there’s nothing stopping us from using the conventional deadlift technique even with a trap bar.

- Neutral-grip: the handles face each other, allowing us to grip the barbell without internally rotating our shoulders. For many of us, this is a more comfortable position. It’s also great for bulking up our upper traps.

- Greater grip strength: because the handles face one another and are fixed in place, there’s no possibility of them rolling out of our hands. This makes our grip much stronger, allowing us to lift heavier weights without our grip strength limiting us.

- Raised handles: raised handles shorten the range of motion of our deadlifts, often allowing us to lift slightly heavier weights, which can be a boon for people with limited hip mobility. Furthermore, raised handles shift the center of gravity below the grips, making the trap bar less likely to rotate or wobble.

- Standard-height handles: most trap bars also include handles at normal depth, allowing us to deadlift with a normal range of motion. The downside is that when gripping these lower handles, the trap bar can wobble. As a result, some companies (such as Kabuki) make their standard handles slightly higher than the centre of gravity.

Now, these are all great advantages, making the trap-bar a great tool for getting more out of our deadlifts. The downside is that virtually none of these benefits apply to any other lift. We might be able to get away with overhead pressing with some trap bars, and they’re good for doing farmer carries with, but we can’t use them for squatting, bench pressing, or curling.

Overall, trap bars are a great specialty barbell to have, but they aren’t essential, and they won’t replace a standard barbell.

Safety-Squat Bars

A lot of big powerlifters lack the shoulder mobility to comfortably reach back and grab a standard barbell. Safety bars solve that problem by adding handles to the front of the barbell.

Furthermore, the low-bar back squat position that powerlifters favour isn’t necessarily ideal for building muscle, and it can be a bit hard on the hips. That all depends on the person, of course, but it’s common to run into issues with it. Safety bars help by shifting the centre of gravity forward, clearing up space in the hips and allowing for a deeper range of motion.

There’s another way to get both of those benefits, though. Instead of holding handles we can hold the barbell in a racked position in front of us. And instead of shifting the weight forward by changing the shape of the barbell, we can simply hold the barbell in front of us. That gives us the front squat:

The front squat is already better for building muscle and gaining general strength (and improving posture) than the low-bar back squat, so we don’t really have a problem that needs solving here. I understand why powerlifters love these barbells, and they’re certainly great, but most of us are better served by simply front squatting.

Multi-Grip “Swiss” Bars

Swiss bars have a number of different grip options, ranging from slightly pronated to fully neutral, making them a more extreme version of a curl bar. They can be used for a few different lifts:

- Neutral-grip bench press

- Neutral-grip overhead press

- Neutral-grip rows

- Hammer curls

Using a neutral grip changes the muscles we’re emphasizing with our lifts. For example, instead of targetting our biceps when curling, we target our brachialis. So having access to some extra variation can certainly help when building muscle.

Swiss bars are only good for a few smaller exercises, and none of them are all that essential, especially if we already have a curl bar. Still, swiss bars are a handy piece of equipment to have around.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Much Does a Barbell Weigh?

A standard Olympic barbell, which is what you’ll find in most gyms, weighs 45 pounds or 20 kilos. But there are exceptions. Women’s barbells often weigh closer to 35 pounds, curl-bars usually weigh 25–30 pounds, and there are a variety of specialty bars that each weigh slightly different amounts.

But the typical barbell at most commercial gyms is a multipurpose Olympic barbell, and it weighs 45 pounds / 20 kilos.

Can You Build Muscle With Just A Barbell?

Absolutely, yes. Barbells are one of the best tools for building muscle and gaining strength. It can be handy to have access to dumbbells, exercise machines, and cable stacks, and that’s one of the reasons why commercial gyms are so popular, but those are just conveniences. You can spend a lifetime training with just a barbell and never be limited by it.

Etymology: Why Is a Barbell Called A Barbell?

At first, there were dumbbells: weights with handles that are used for strength training. Then they were attached to longer bars, becoming bar + dumbbell, or barbell.

Summary: the Best Barbells to Buy

For strength training and hypertrophy training, you should buy either a power bar or a multipurpose barbell. Brands like Eleiko that make fantastic barbells, but Rogue makes even better ones, and their barbells are less than half the price. As a result, we recommend buying the Ohio Power Bar or Ohio Bar.

Here are my recommendations. Note that these are affiliate links:

- Ohio Power Bar (for men—$295–480): this is the gold standard of strength training barbells, and it’s just as good for bodybuilding and hypertrophy training. It’s not good for Olympic weightlifting or CrossFit. It’s made in America and ships internationally, with both European and Australian distributors. The knurling is the best in the world, it will last a lifetime, and it comes in zinc or stainless steel (with chrome sleeves). I have one of these and love it.

- Ohio Bar ($295–445): this is the best multipurpose barbell on the market, and even though the knurling isn’t aggressive, it’s still lightyears better than the knurling on most barbells. It’s good for strength training, Olympic weightlifting, and Crossfit, and it’s perfect for bodybuilding and hypertrophy training. I have two of these and love them both.

- Bella Barbell (for women—$315): not all women need a women’s barbell, but if you’re shorter, lighter, or have smaller hands, you might find that a women’s barbell suits you better. They’re around 30% lighter, half a foot shorter, and have a thinner diameter (25mm), making them easier to grip with smaller hands. Plus, unless you’ll be lifting 600+ pounds, there’s no downside to them.

If you’re looking for an even cheaper barbell, Rep Fitness makes a decent barbell at a very low price. Bells of Steel are also popular. They aren’t as famous for their quality, but as we said at the beginning, you can build muscle with almost anything.

If you want to get a second barbell, there are some interesting specialty bars to choose from, some of which are great for gaining size and strength:

- Rogue Curl Bar ($195): curl bars are by no means necessary, but they’re a handy backup barbell to have around, and make almost every accessory lift a little bit easier or more enjoyable. Rogue’s curl bars are great because they’re made out of high-quality steel, the volcano knurling is the best in the world, and they’re plated in zinc.

- Rogue Trap Bar ($375): there’s no doubt that trap bars are great for deadlifting. For most of us, they’re even better than traditional barbells. However, they’re expensive, they take up a lot of room, and they’re only great for the one lift. Plus, these aren’t made to the same quality standards as a regular barbell, so they may not age as well.

If you don’t know what to buy, my recommendation would be to get an Ohio Power Bar in either stainless steel or black zinc. Then, if you still have money left over, buy a curl bar. That will allow you to alternate between a big compound lift (such as a bench press) and an accessory lift (such as an underhand row) during your workouts, keeping them short and efficient.

If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds in these principles, check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. Or, if you’re still skinny or skinny-fat, try our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. If you liked this article, you’d love our full programs.

Shane Duquette is the co-founder of Outlift, Bony to Beastly, and Bony to Bombshell. He's a certified conditioning coach with a degree in design from York University in Toronto, Canada. He's personally gained 70 pounds and has over a decade of experience helping over 10,000 skinny people bulk up.

Wow, that was an incredibly thorough write up, I love it. I’m currently saving up for a Rogue Ohio Bar. All my equipment is mid-tier stuff, nothing special. And my current bar is fine, but I want to own one really nice thing and it’s going to be the bar.

I’ve got both the Ohio Bar and the Ohio Power Bar now. I love both. I think you’re going to love yours, too. Definitely worth it 🙂

Well, to be more precise, my wife encouraged me to get the Power Bar and then claimed the Ohio Bar as her own 😛

[…] aggressive knurling, and it feels amazing. (If you want to go down the rabbit-hole on barbells, check out Shane’s barbell guide here.) I got brightly coloured bumper plates, and the bench I have (Thompson Fat Pad with the shorty […]

Soo, since you have all three Ohio Bar, Ohio Power Bar and Ohio Cerakote Bar … which gives the best grip? I am really liking the Cerakote Bar as my endgame bar. But it says it only has “standard knurl” and has no center knurl. They don’t have Cerakote Power Bar darn it :D.

Can you go more in-depth on the differences between Ohio Power Bar and Ohio Cerakote Bar? I mean the Cerakote is only slightly more expensive, isn’t the extra durability (and looks hehe) worth the weaker knurl and lack of center knurl? How much difference there is?

Jan! Always good to hear from you, man.

You can indeed get a Rogue Ohio Power Bar in cerakote. However, the cerakote bar isn’t my favourite for grip. On the plus side, the matte cerakote coating isn’t as slippery as uncoated metal. But on the downside, it does muddy up the knurl a bit.

The nickel coating seems to do a better job of preserving the knurl. It’s nice and crisp. Feels great.

For aesthetics, I don’t know. The matte cerakote looks great from a distance, but up close it’s not quite perfect. I’m leaning towards the black nickel / black oxide for aesthetics. The cerakote does look awesome, though. I think you’d be happy with any of them. And obviously if you want colour, you’ve got to go cerakote.

For the cerakote, imagine that someone took a regular barbell and did a really nice job of spray painting it with durable matte spraypaint. Does that look better than nickel or steel? I don’t know.

I’ve had my barbells for about a year now and all of them are still in perfect condition. I haven’t had to do any maintenance on them whatsoever. And we live near the ocean in Cancun, so I was worried heat and humidity might pose a problem. I can’t compare the durability until one of them starts to show signs of wear and tear.

One other thing I’ll say is that even the regular Ohio Bar has absolutely phenomenal knurling. If you’re used to the barbells at commercial gyms, you’ll be absolutely wowed any of Rogue’s barbells. They’re so far beyond anything you will have used in the past. You can’t make a bad choice.

Of my barbells, I prefer my black nickel Ohio Power Bar. It’s rough on my hands, but I don’t mind, and I love how secure the grip is. My wife prefers the Ohio Bar. She has no problem gripping it and the knurling doesn’t tear into her hands as much.

What about the brands in Europe?

I believe it’s similar. With Rogue, for instance, they have a European branch: https://www.rogueeurope.eu/

You seem to be very read up on barbells and I am wondering if you would recommend the Rogue Echo Bar 2.0 for a garage gym. My biggest worry is that the increased humidity and varying temperatures in the garage will lead to oxidation of the zinc. Ideally this would be an intermediary bar until I could afford the best of the best. Would you recommend making this investment considering it is relatively inexpensive and in stock?

Hey Spencer,

Zinc isn’t totally 100% ideal for resisting oxidation, but it’s pretty great! I’ve got a zinc barbell and curl-bar, and after 2 years, there’s no rust whatsoever. My home gym is inside, but I also live in Cancun, in sight of the ocean, and it’s about as humid as it gets. All of the other metal in the house rusts quite aggressively, but the zinc barbells haven’t yet.

If you’re keeping your barbell in the garage it will eventually rust, and so it will require maintenance. And over time that maintenance will wear away the zinc plating. But your barbell will be quite durable, and even as it ages, you can just keep maintaining it. Some oil and a brush and you’ll be set, and it might be years before you even need to worry about that.

Rogue makes great barbells. I think you’ll get a ton of value out of the Echo bar.

Men’s Olympic barbells DO have center knurling. Women’s do not.

Also, weightlifters DO use the squat for overall strength (and hypertrophy if that is needed). They in fact do more back squats than front squats. Fronts are done specifically for clean recovery strength.

Hey Dresdin,

It really depends. For instance, Eleiko puts centre knurling on their Olympic weightlifting barbells, Rogue doesn’t. And different training Olympic weightlifting programs will favour different squat variations, and most will probably use a mix of squats, but I can check on that to see how dominant front squats are (or aren’t). Thank you!

Hello

This is very useful article who are interested to set their career as fitness trainer or squat coach. Even you explain all small things which must know people. Thank you for sharing amazing content to us.

Our pleasure, Jack! So glad you liked it 🙂

Hello Shane,

Excellent article!

I’m over 50 with a tear on the left shoulder and a cyst on the right shoulder. I’m also a triathlete. I need to strengthen both shoulders in order to avoid surgery for now.

What do you recommend for a barbel? I made a DIY power / CrossFit / Ninja Rack OUTSIDE. I believe I would benefit from a multipurpose barbell? Can you please assist me on which brand, length, coating, etc is best? I need a reasonably priced barbel.

I just need to be in good health. Looks would be a plus.

Thank you in advance!

Sometimes when you’ve got funky shoulders, it can help to do dumbbell pressing and push-ups instead of the barbell bench press and overhead press. You get more freedom of movement in your joints that way. But if barbell training suits you well, I think you’re right—a multipurpose barbell sounds great for you.

Rogue has the best value, offering high-end quality and moderate prices. You train outside so you want a fairly robust coating on the barbell to prevent rust. Their stainless steel Ohio Bar is often considered the gold standard for that. But you want something reasonably priced, so I’d recommend zinc instead. Perhaps their black zinc Ohio Bar. If you notice the beginnings of rust, just clean it with a brush and some oil. Just be warned that the finish will fade over time, leaving it looking distressed.