The Deadlift Hypertrophy Guide

The deadlift strengthens us from our forearms down to our calves. In fact, it’s such a good indicator of overall strength that it’s the only lift in both powerlifting and strongman competitions.

For stimulating muscle growth, the deadlift is more controversial. Most casual gymgoers skip it. Many bodybuilders do, too. And it’s easy to see why. Deadlifts are hard to learn, challenging to do, and difficult to recover from. But if you do them, they’re worth it.

If you want a bigger, stronger, and better-looking body, there’s no better lift than the deadlift. It stimulates the most overall muscle growth, it develops full-body strength, and it thickens some of our most impressive muscles.

- What is the Deadlift?

- What Muscles Does the Deadlift Work?

- How to Do the Deadlift

- Are Deadlifts Good for Building Muscle?

- Building a Strong & Healthy Spine

- Why the Conventional Deadlift is Best for Building Muscle

- Conventional Deadlift Alternatives

- How to Increase Your Deadlift Strength

- How Much Should You Be Able to Deadlift?

- Summary

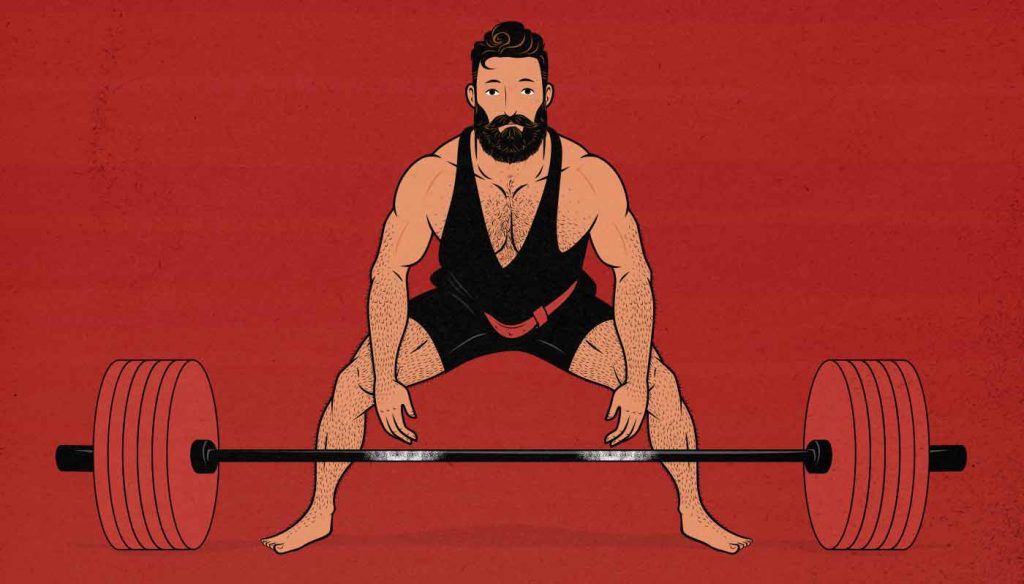

What is the Deadlift?

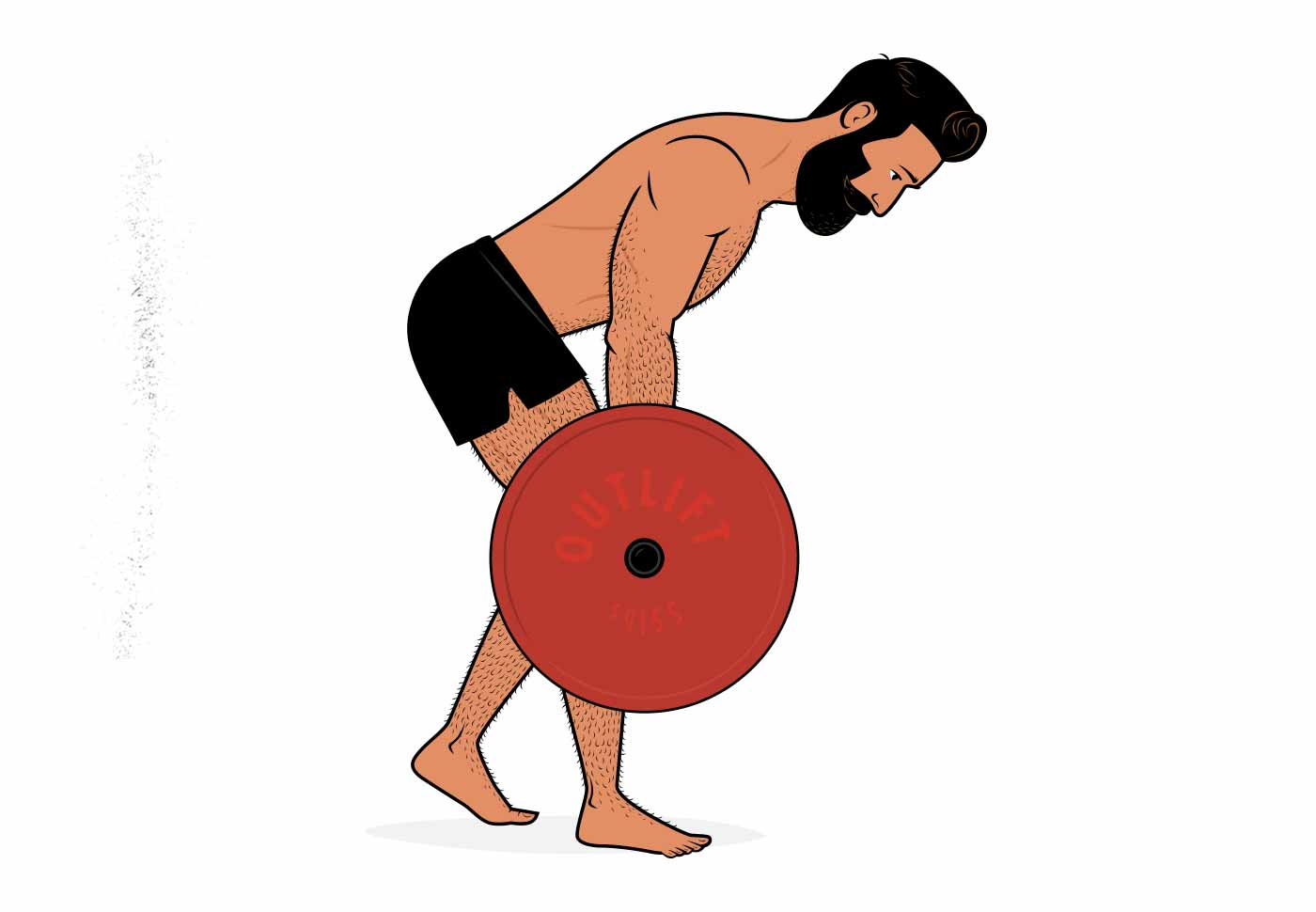

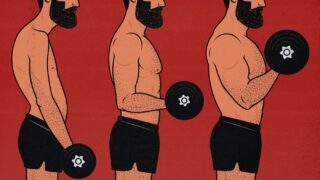

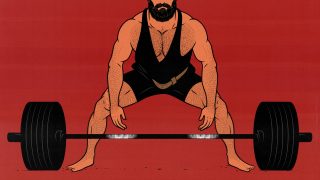

The deadlift is the biggest compound barbell lift, famous for stimulating more overall muscle growth than any other lift. It gets its name from the fact that we lift the barbell from a “dead” position on the floor, like so:

Lifting something from the floor is a natural, practical movement, giving the deadlift tremendous carryover to general strength. And because the weight is so heavy, the stress toughens our spines, strengthens our tendons, and hardens our bones, making us more resilient overall.

Some argue that if our goal is to develop long-lasting general strength, why risk loading up our spines so heavily? Why risk slipping a disc? But that line of thinking forgets that we adapt. Deadlifting is stressful, yes, but that’s how we grow bigger, stronger, and tougher. And if we do it properly, we can minimize the risks while maximizing the benefits.

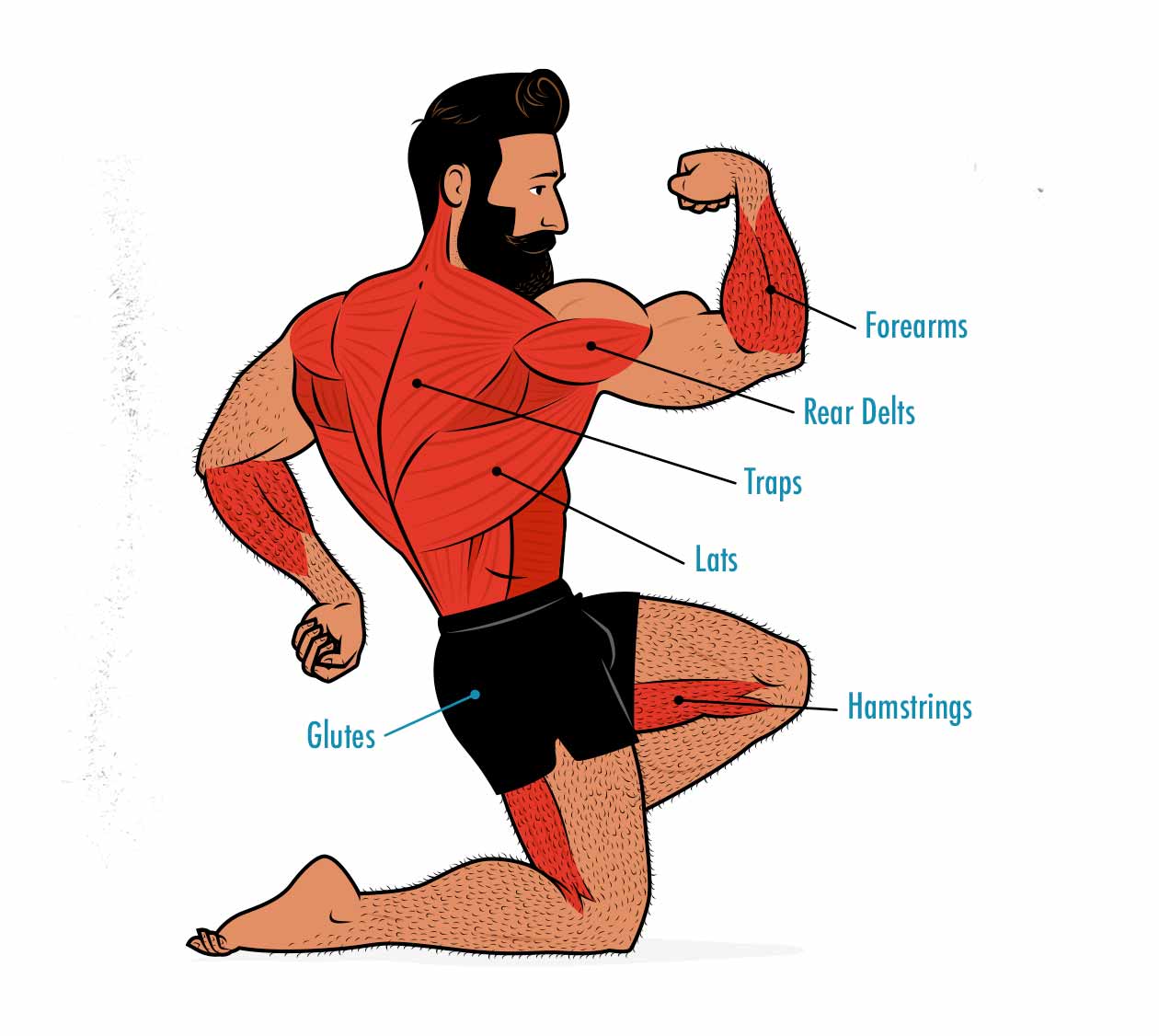

What Muscles Does the Deadlift Work?

Main Muscles Worked

Deadlifts challenge hundreds of muscles, tendons, and bones throughout our bodies, but they’re best for working our hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors, and traps.

The deadlift trains our hips through a deep range of motion, making it perfect for building bigger glutes. While doing that, the weight is held in our grips and hanging from our traps and rear delts, with our lats pulling it close. All of these muscles are worked hard enough to grow.

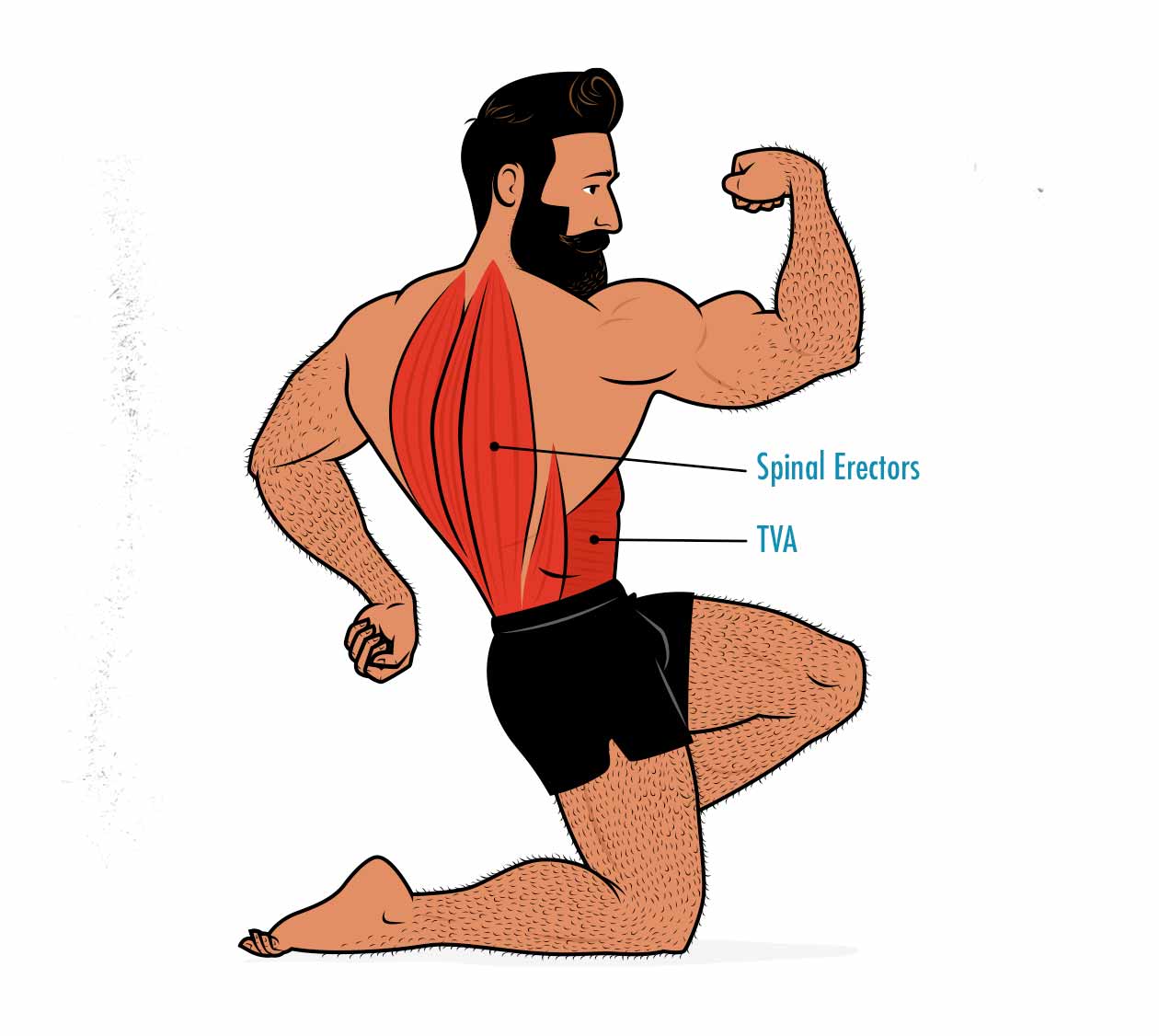

Where the deadlift truly shines, though, is in its ability to work our deeper back muscles—our spinal erectors and transverse abdominis muscles (TVA). These are the muscles that hold our backs straight as we lift the weight up.

The deadlift is technically a hip hinge—an exercise for bulking up our glutes and hamstrings. But because of how hard our back muscles are worked, it’s best described as a full-body lift for the entire posterior chain.

What Should Feel Sore After Doing Deadlifts?

The deadlift is a hip hinge, working our glutes and hamstrings through a deep range of motion. Feeling soreness in those muscles a day or two after working out is, and it’s what most people expect. But remember, the deadlift also trains our spinal erectors, so it’s also common to have a sore lower back after deadlifting.

People often worry when their lower back burns after a hard set of deadlifts or when it gets sore the next day. But the deadlift trains the lower back. So just like all of our other muscles, our lower backs will burn, get a pump, and get sore afterwards.

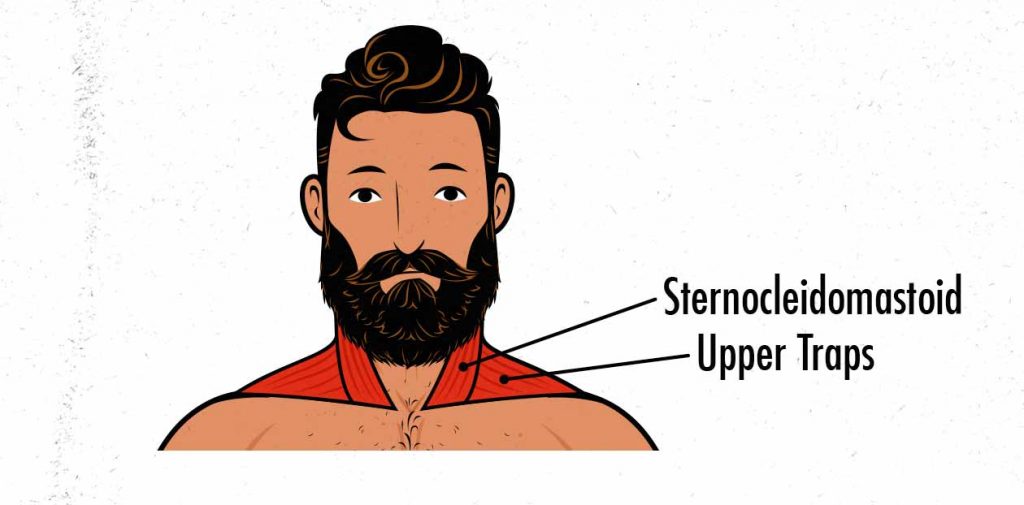

Does the Deadlift Work the Neck?

Of all the big compound lifts, the deadlift is the one that’s the most likely to bulk up your neck. In fact, if you count your upper traps as part of your neck, then the deadlift is a great neck exercise. The deadlift will absolutely bulk up your traps.

However, if you’re also interested in bulking up your sternocleidomastoid, which is the muscle that will make your neck thicker, then the relationship between the deadlift and your neck becomes more tenuous.

If you deadlift with classic technique, eyes forward, keeping your spine neutral from top to bottom, then the deadlift probably won’t stimulate any neck growth whatsoever. This is generally considered the safest deadlift technique, and it’s our default recommendation. (We aren’t sticklers about it, though.)

On the other hand, if you tend to look up while deadlifting, then as the barbell pulls against your collarbones, your sternocleidomastoid might get stretched out under a heavy load, which can cause some neck growth. However, that brings the very top of your spine out of a neutral position, and even though that area of your spine won’t be bearing any load, some spinal experts argue that it’s more dangerous. (There’s very little evidence one way or the other. It depends on how cautious you want to be.)

Regardless, no matter what position your neck is in while deadlifting, there’s no real guarantee that your neck will grow. And even if your neck does grow, it’s unlikely that it will grow very quickly or very much.

As a result, if you want a thicker and stronger neck, I would recommend doing some dedicated neck training. You won’t need extra work for your upper traps, but you’ll probably want some extra work for your sternocleidomastoid.

How to Do the Deadlift

The conventional deadlift starts with the barbell on the floor. From there, you get in close, brace your core, and pick it up. It’s a simple, brute strength lift, but there are still quite a few things you can do to make it safer and more effective.

Here’s Marco teaching the conventional barbell deadlift:

As you do your deadlifts, you might want to keep a few cues in mind:

- Chest high: keep your chest high and your lats flexed hard.

- Sit back: Sit your hips back and feel the tension build on your glutes and hamstrings. This is where your power will come from.

- Tight armpits: before you lift the weight, tighten your armpits as if you’re deathly afraid of being tickled.

- Pull the slack out of the bar before you lift it. If there are a few hundred pounds on the bar, put a couple of hundred pounds of pressure on the bar before you try to heave it up. That will pull the slack out of the bar and give your back muscles a chance to engage.

You probably won’t need to overthink it, though. By the time you’re an intermediate lifter, deadlifts should feel fairly intuitive. Trust that intuition. Your back is strong and so are you.

Are Deadlifts Good for Building Muscle?

Why Do Bodybuilders Eschew Deadlifts?

Deadlifts have a reputation for being great at developing strength, bone density, and tendon health, but they’re often accused of being too fatiguing to be used as a hypertrophy lift. Bodybuilders will often argue that deadlifts are great for bulking up our hamstrings, hips, forearms, and entire backs, but at the cost of leaving our lower backs fried, our hands beaten up, and draining all of our energy.

There’s some truth to that idea. If you deadlift poorly, or even with the wrong goal in mind, you get a lift that stimulates a lot of muscle growth but generates even more fatigue. So if you’re deadlifting with the goal of gaining muscle mass, there are a few issues we need to address:

- Adjusting the lifting tempo. When deadlifting heavy, most people heave the barbell up and then drop it back down, removing the eccentric part of the lift. The idea is that you’ll save your strength and reduce your injury risk. The problem is that you’ll build more muscle if your lifts have both a concentric and eccentric portion to them. That means that if your goal is to build muscle, you should lower the weight down under control. So long as you maintain proper positioning while lowering the barbell, it shouldn’t increase your risk of injury. And if you can’t maintain proper positioning while lowering the barbell, you should lower the weight until you can.

- The starting position and your hips. The starting position of the deadlift is determined by the size of the plates you’re using. Almost always, those are standard 45lb plates. The problem is that the mobility you have in your hips might not quite line up with that depth. More on this in the range of motion section.

- The range of motion. Different variations of the deadlift use different ranges of motion. Trap-bar and sumo deadlifts use smaller ranges of motion, which tends to make them worse for gaining muscle mass. Conventional deadlifts use a larger range of motion, making them better for bulking (at the cost of being more tiring).

- Lining the limiting factor up with your goals. Different deadlift variations will cause you to fail for different reasons. If your back gives out first, then the deadlift will primarily train your back (which is common in the conventional deadlift). If your hips give out first, then it will primarily train your hips (which is common in the sumo deadlift). You can pick your deadlift variation based on which muscle groups you’re most eager to stimulate. For gaining overall size, we recommend the conventional deadlift.

- Fixing grip strength. Many people fail deadlifts due to a lack of grip strength, especially when they’re new to it. This needs to be solved by using a mixed (over/under) grip, a hook grip, using chalk, using lifting straps, or using accessory lifts to buff up your grip strength. Otherwise, the deadlift will be reduced to a convoluted forearm exercise.

- The fatigue problem. The deadlift is a very fatiguing lift, especially if you’re being limited by your spinal erector and/or grip strength. Unlike the other big compound lifts, it’s often wise to do deadlifts with a lower training volume and a lower training frequency, but with more assistance and accessory work.

This is all to say that most people program the deadlift to improve general strength rather than muscle size. With a few simple tweaks, though, it can be a great exercise for gaining muscle mass, too.

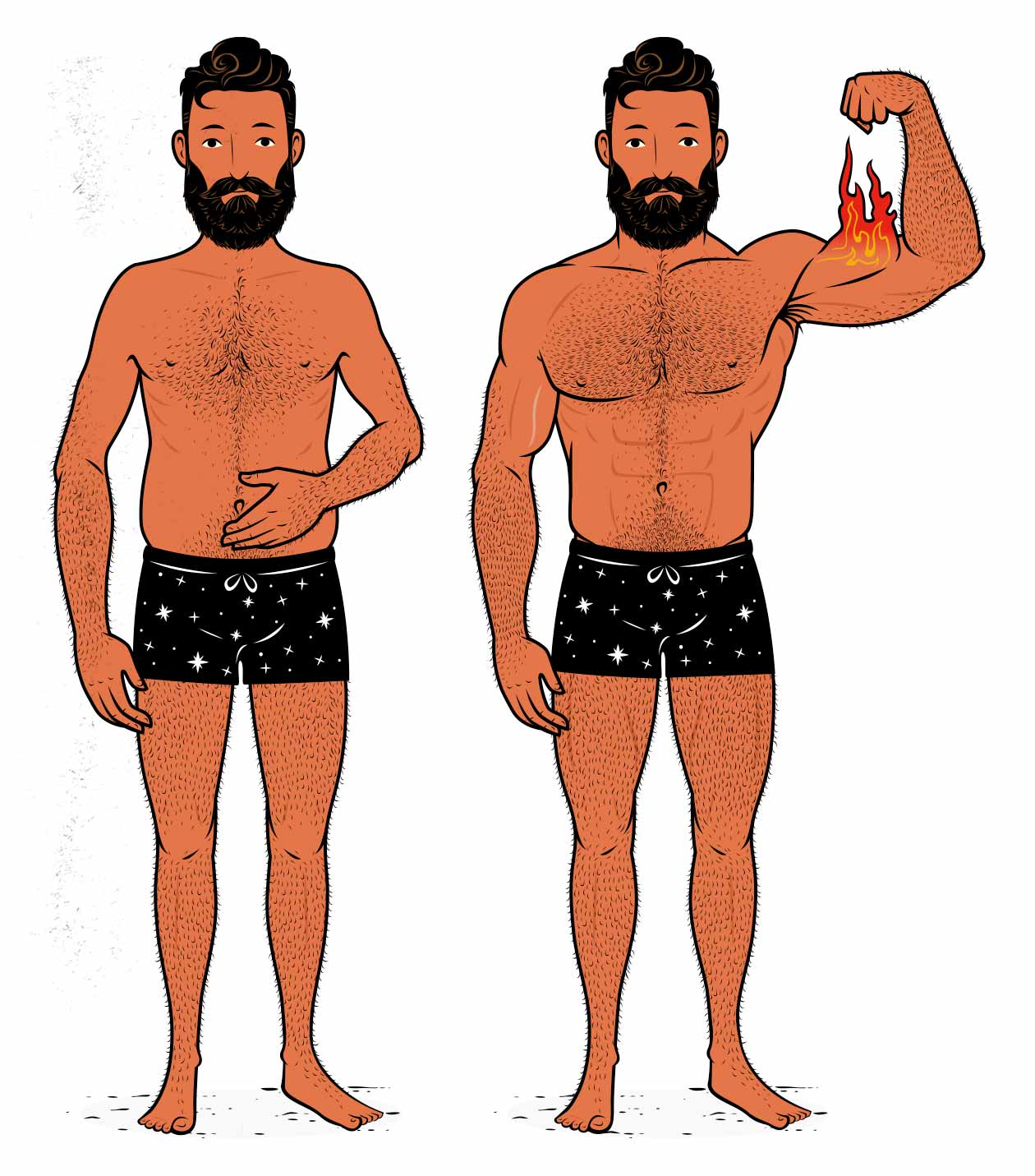

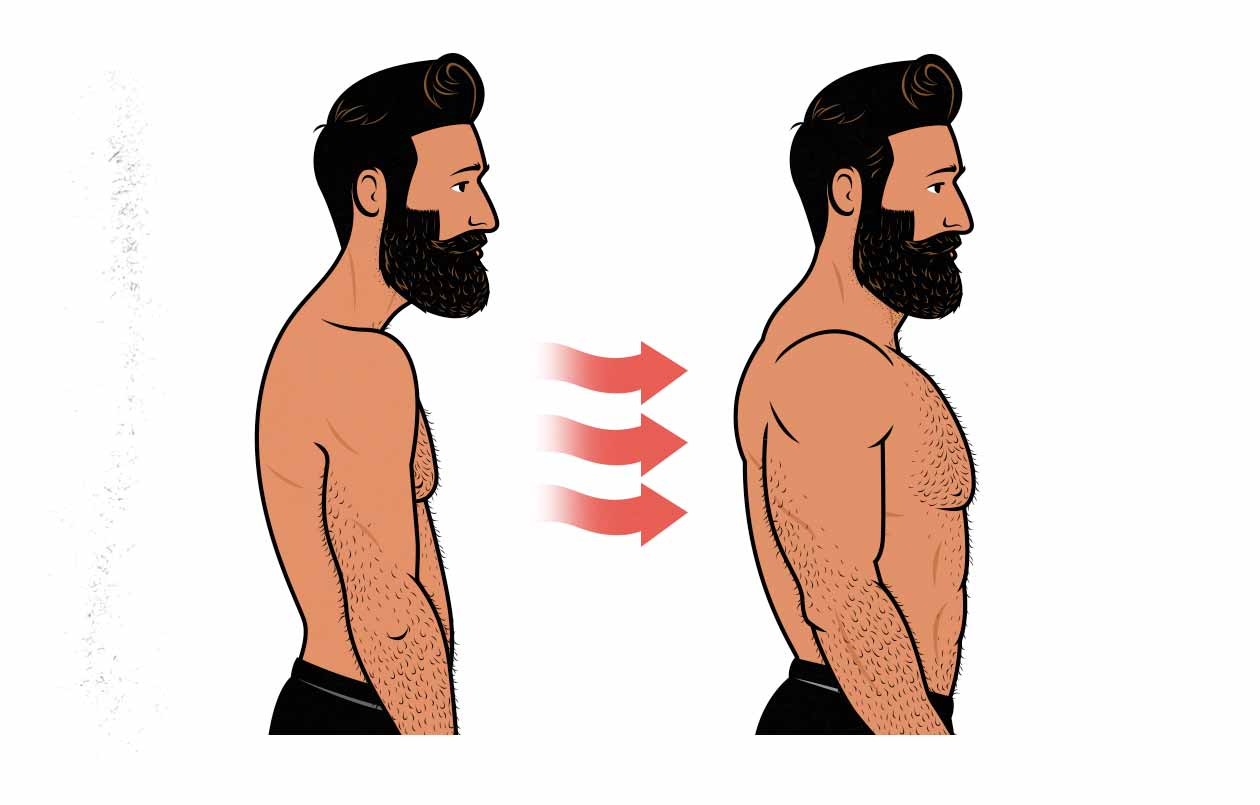

Do Deadlifts Improve Our Aesthetics?

For aesthetics, deadlifts are criminally underrated. They develop the “yoke” muscles that make us look stronger and more dominant: the traps, the forearms, the spinal erectors, and the glutes.

- For guys with naturally thinner bodies, bulking up our spinal erectors is especially important. Like the front squat, deadlifts will make us markedly thicker.

- For guys with longer and thinner necks, nothing will improve your appearance like building a tall set of traps to rest your neck upon.

- For guys with lankier arms, nothing will bulk them up like a pair of burly forearms, and nothing will cap them like a pair of harder and thicker hands.

If you agree with the formidability argument of aesthetics—that men who look more formidable look more attractive, then deadlifts are a great tool for improving your aesthetics. Plus, when we surveyed women, they also expressed a preference for men with proportionally stronger butts. Deadlifts are one of the best lifts for building a bigger butt.

Yes, deadlifts are difficult. But if you’re trying to improve your appearance, best to have a body that looks like it’s capable of doing difficult things.

Minimizing Deadlift Fatigue

Deadlifts are notorious for being hard. We’re engaging almost every muscle in our bodies, we’re lifting tremendous amounts of weight, and that weight is being borne by our spines.

That may not sound like a bad thing yet. After all, squats are hard, too. In fact, all of the best bulking lifts are hard. And yet it’s these big lifts that give us most of our results. A single set of heavy deadlifts can replace an entire mediocre workout. However, deadlifts are disproportionately fatiguing.

To put this into perspective, let’s compare the deadlift against the squat in terms of its ability to generate fatigue. Deadliftsand squats both wedge us under heavy loads our spines must support. They’re similar in many ways.

As soon as you look at how squats and deadlifts are programmed, though, you realize something odd is going on.

- People squat hard and often: Programs like Starting Strength recommend starting every workout with three sets of heavy squats. StrongLifts 5×5 recommends starting with five heavy sets of squats. Perhaps you’ve even heard of programs that recommend squatting every day (such as Smolov). That’s a lot of squatting!

- People deadlift far more sparingly: Starting Strength and StrongLifts both recommend deadlifting 1–2 times per week, saving them for the end of the workout, and doing just a single set. They recommend squatting six times as much as deadlifting. And there isn’t a single (sane) program that recommends deadlifting every day. That’s because deadlifts are harder on us than squats. But why?

Why are deadlifts so fatiguing? There are a few theories. Most of it comes down to the fact that deadlifts put a greater load on our spines while our torsos are more horizontal, increasing sheer stress, axial loading, and tiring out our spinal erectors. And when our spinal erectors are tired, we’re tired.

Heavy deadlifts can turn new lifters into puddles for days. It can be hard to sit upright in a chair, let alone get up from one. It can even be harder to sleep. Moreover, holding such a heavy barbell can tear up our hands. When our hands are torn up, we don’t want to hold anything.

If we’re just trying to gain muscle size, why should we put ourselves through that hardship? Why not spend our energy doing other exercises instead? The answer to this question is simple: to stimulate as much muscle growth as a deadlift, we’d need to do a dozen other lifts, including ones that load our spines up heavy. We’d accumulate the same fatigue, just less efficiently.

There’s a stronger version of that argument, though. Even if we do decide to deadlift, why not choose an easier variation, such as a Romanian deadlift? It’s the same movement pattern, but it’s much less fatiguing. Plus, it works your hamstrings harder.

There are a few downsides to swapping out conventional deadlifts for Romanian deadlifts:

- Work capacity. Becoming accustomed to doing more taxing lifts will increase our work capacity, allowing us to handle higher volumes of harder lifts. This is especially true if we put extra emphasis on bulking up our spinal erectors, giving our spines a bit of extra support.

- A tougher spine. The reason that deadlifts are so tiring is because of all the stress on our spines. But that stress will make our spines stronger. That will make every other lift easier.

- Denser bones. Going into the realm of speculation here, there seems to be a strong link between bone mass and genetic muscle-building potential. First, the research of Casey Butts, PhD, found that guys with more bone mass can build more muscle. Second, bone researchers have noticed that when people lose bone density, their muscle mass tends to decrease as well. I think including some lifts in our routines that are good for building denser bones is not only healthy, but also a good idea for longer-term muscle gains.

- Time efficiency. It’s true that deadlifts are fatiguing per unit of muscle growth, but if we also factor in that deadlifts stimulate a tremendous amount of muscle growth per unit of time, they start to look a bit better. Spending fifteen minutes deadlifting per week might yield a disproportionate amount of fatigue, but it will also yield a disproportionate amount of overall muscle growth.

Besides, most smart programs take into account that deadlifts are fatiguing anyway. That’s why you’ll often see deadlifts programmed with a lower volume and frequency.

Min-Maxing the Range of Motion

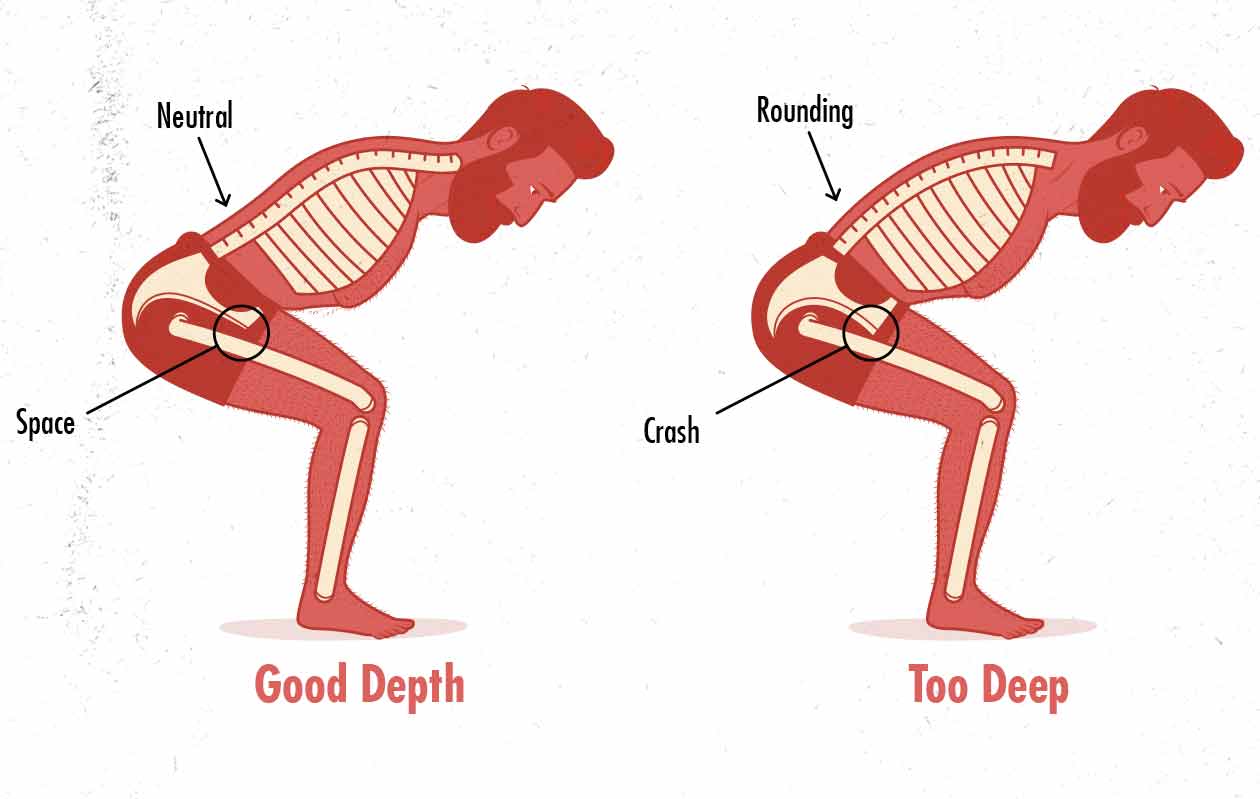

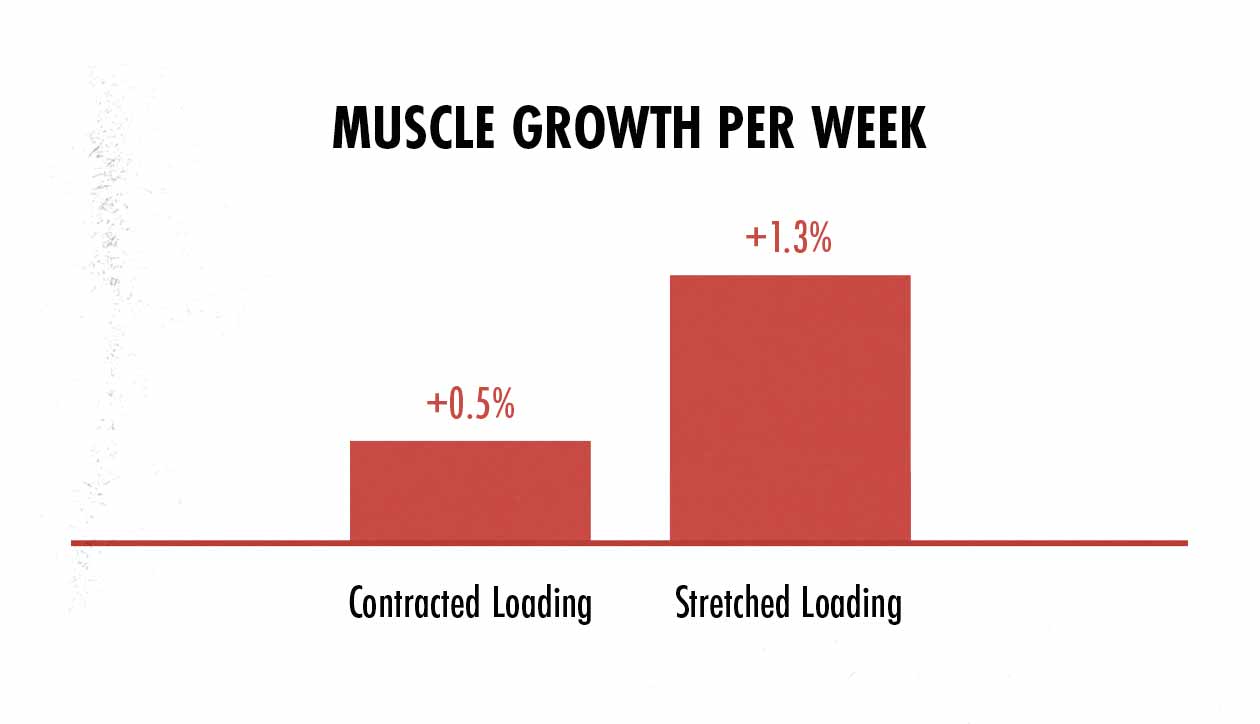

Our muscles grow best when we challenge them in a stretched position. That’s one of the reasons the deadlift is so good for building muscle. The bottom portion of the lift is the hardest, working our hip flexors under a deep stretch.

Because the most important part of the deadlift is the bottom. We want to deadlift as deep as possible, getting a nice full stretch on our glutes. However, while going deep is great, going too deep can jam up our hips and force our lower backs to round. And since everyone is built differently, everyone’s ideal depth is different.

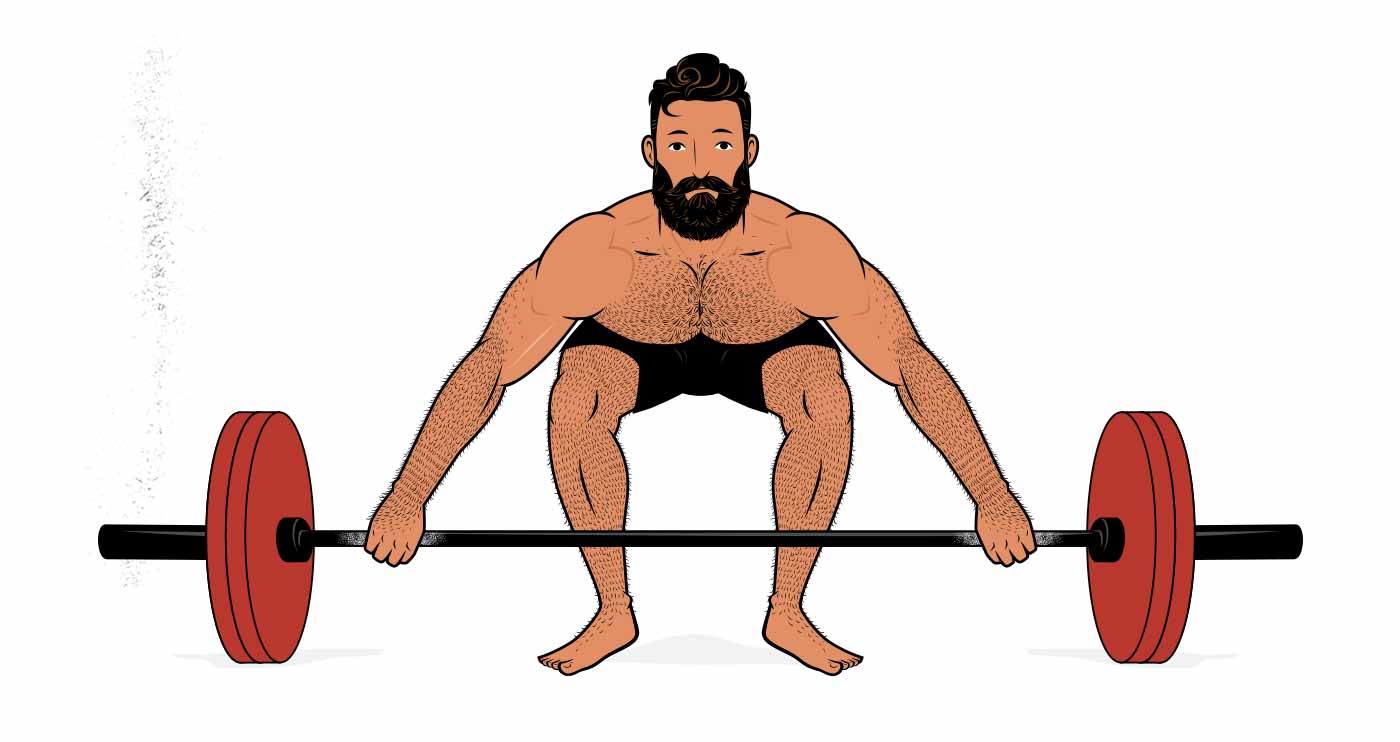

For people with average bone structures and decent posture, deadlifting from the floor is a good default. Almost all of us will be able to get into a position like the good fellow on the left:

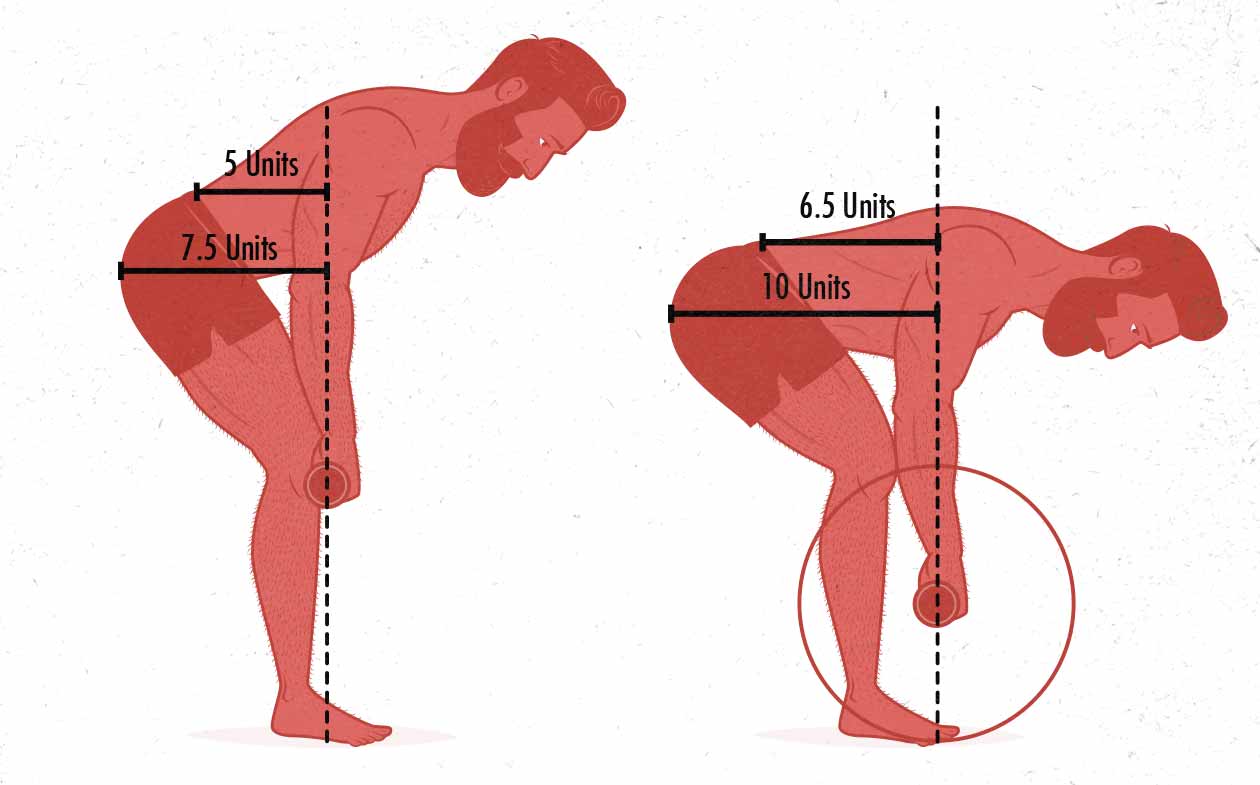

But let’s also talk about this guy on the right. Most people can get somewhere between 110–130° of bend in their hips (source). The deadlift typically requires about 115° (source). So when some people set up for the deadlift, their femurs crash into their pelvis, forcing them to round their lower backs to reach the barbell. That throws their backs out of proper alignment, making deadlifts more dangerous.

If you don’t have the mobility to grip the bar without rounding your back, all hope isn’t lost. Try going through this list, starting at the beginning and working your way down:

- Trap-bar deadlifts. Most trap bars reduce the range of motion by a couple of inches, and they also allow you to bend less at the hips by bending more at the knees, allowing everyone to get into a proper starting position. However, not everyone has a trap bar.

- Angling your knees outwards. To do this, angle your feet out to about 30°, plant them firmly on the floor, and then “drill” them in to angle your knees outwards. As always, line your knees up over your second toe.

- Using a slightly wider conventional stance, even if that means moving your arms out a little bit wider.

- Using a narrow sumo stance, where you bring your knees right outside your grip. This has many of the benefits of a conventional deadlift while freeing up a bit more space in your hips.

- Full sumo stance, which requires quite a bit less mobility in the hips.

- Romanian deadlifts. These allow you to use whatever range of motion you’re comfortable with. The downside is that they aren’t as good for strengthening your back.

On the other hand, if you’ve got great mobility, you may benefit from deadlifting even deeper than the floor. In that case, you might want to try deficit deadlifts, wide-grip deadlifts, or full-on snatch-grip deadlifts. Given the steeper back angle that those involve, they’re even better for building up a bigger and stronger upper back.

However, since deeper deadlifts require using quite a bit less weight, and given that the deadlift is our best opportunity to load our bodies up heavy, you may want to reserve the deeper deadlifts for assistance lifts.

Finally, a mix of different ranges of motions is probably ideal. A November 2014 study found that including some partial range of motion accessory lifts (like rack pulls) alongside full-range-of-motion lifts (like deadlifts) was more effective at improving strength gains than just performing a greater volume of lifts with a full range of motion.

So if a conventional deadlift is deep for you, include some assistance lifts with a shorter range of motion. Romanian deadlifts are great because they still work our hips and hamstrings in a stretched position. Or, if the conventional deadlift is shallow for you, include some deeper assistance lifts. Wide-grip deadlifts are great for that.

Building a Strong & Healthy Spine

The Dangers of the Deadlift

Sometimes you’ll hear that the deadlift is dangerous. It certainly can be. There’s an inherent risk in every lift. What we want to do is minimize those risks while still reaping as many benefits as we can.

There are two common mindsets about lifting, and they seem to be most at odds regarding the deadlift. Some people see themselves as invulnerable and rush into things regardless of the risk. Other people see themselves as fragile and shy away from things that might hurt them.

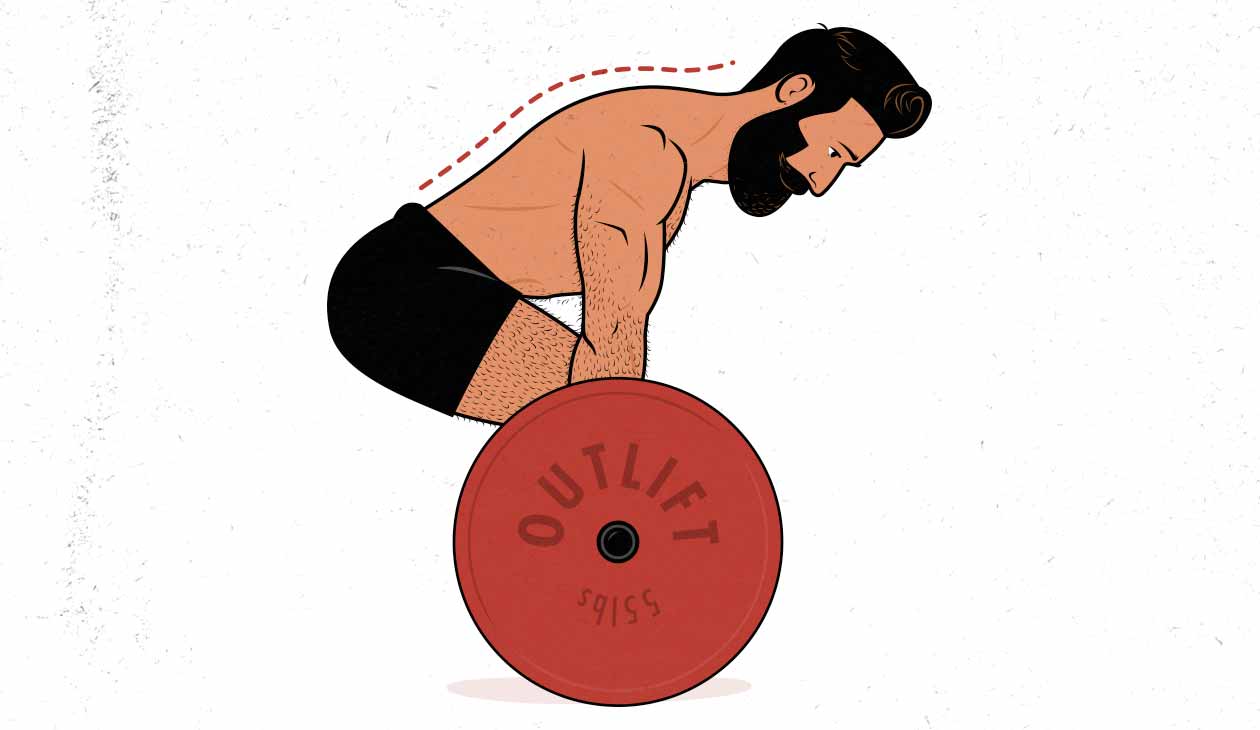

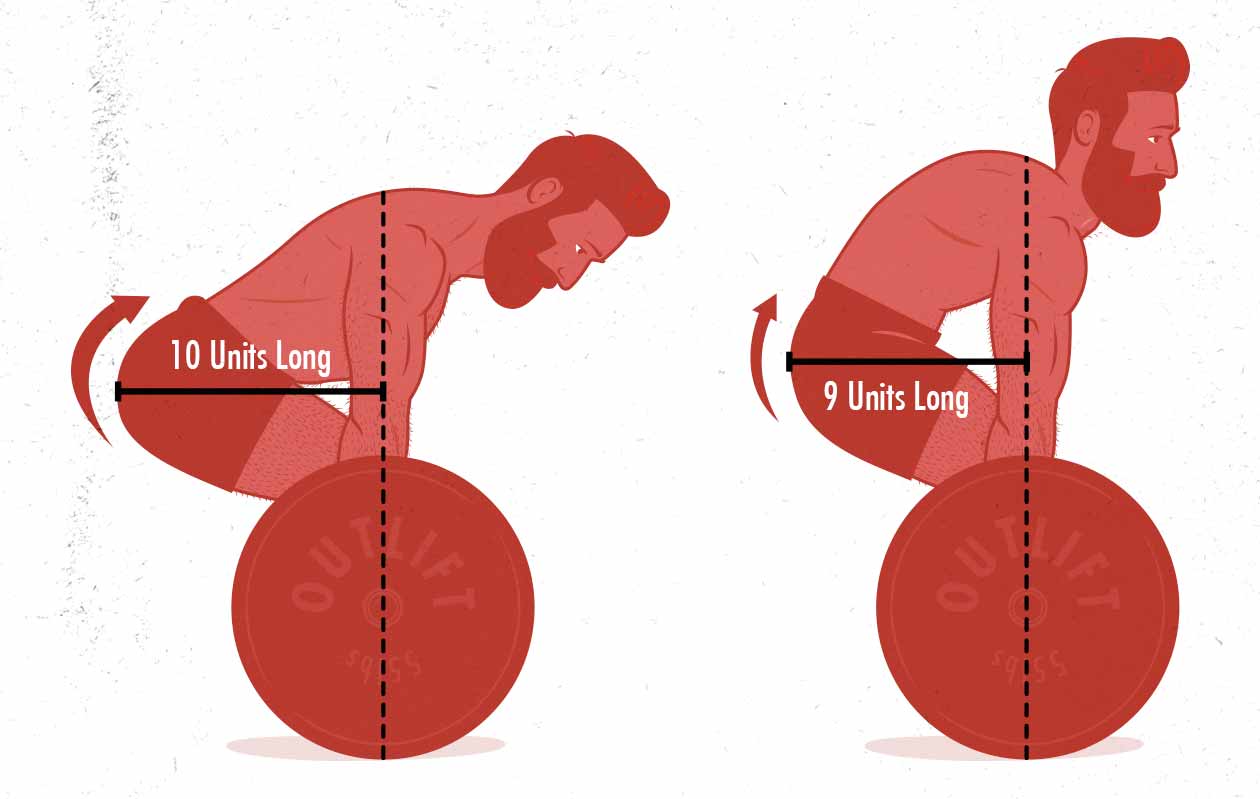

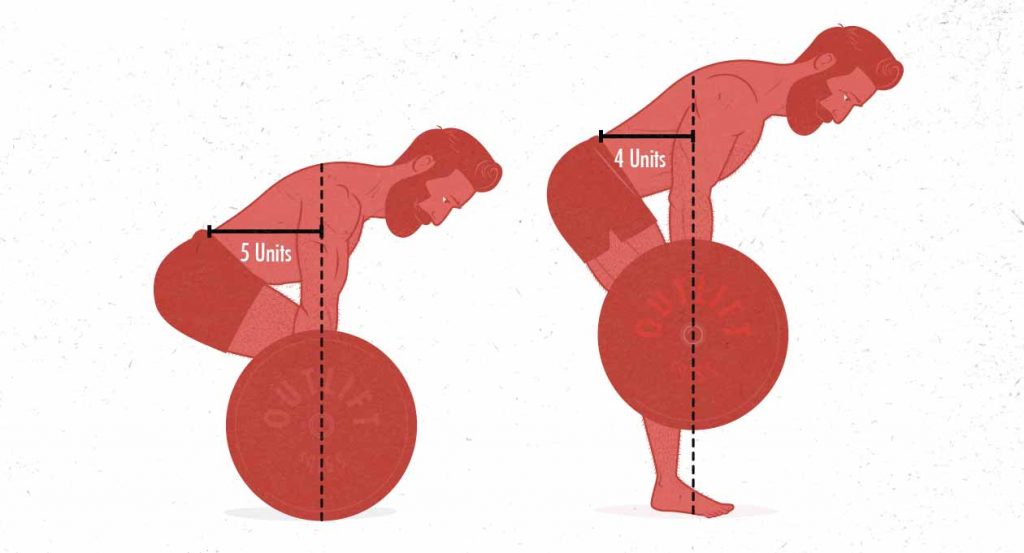

The guys who rush recklessly into lifting will often get hurt, and the deadlift can be especially bad for that. Lifting with a rounded back makes the lift a bit easier on the hips by shrinking the moment arm, like so:

This allows people to rest the weight on their spines and muscle it up with their hips. That’s not good. Our spines are strong and will often hold out, but there’s only so much stupidity they can take. It doesn’t always happen, and it doesn’t always happen right away, and the injuries don’t last forever, but these guys often get hurt.

Cautious people hear about these injuries and psyche themselves out. Any soreness in their lower back worries them. They start seeing the deadlift as an assault on their fragile spines.

But even if you believe your spine is fragile, you still have options. The first is to tiptoe around your spine, never stressing it, letting it become gradually weaker The other approach is to toughen your spine to the point where it isn’t fragile anymore.

Bone in a healthy person or animal will adapt to the loads under which it is placed.

Wolff’s Law, discovered by Julius Wolff, PhD

Progressive Spinal Overload

What’s neat about the spinal erectors is that although they climb up your entire spine, they’re made up of many different little muscles that span just a couple of vertebrae. This means your back might be strong in some places, weak in others. You could have a strong lower back and a weak upper back or vice versa. What’s nice about conventional deadlifts is they do a great job of strengthening our spines from top to bottom.

Progressive overload is a gradual process. A few pounds here, an extra rep there. A slightly stressed disc today, a slightly stronger disc tomorrow. We may start off lifting modest weights with fragile backs, but our spines will adapt along with our muscles, growing tougher as we grow stronger (study).

Intensive training will increase the bone mineral content (BMC) to an extent that the spine can tolerate extraordinary loads.

Spinal loading research by Granhed et al

We do still want to be cautious, though. For example, we recommend deloading now and then, giving ourselves a chance to recover from any minor damage we may have accumulated. Every few weeks, do a couple of easier workouts. Every few months, take a week off. Every few years, take a month off.

You don’t necessarily need to take time off from lifting, just from heavy spinal loading. For example, you could spend a few weeks every year doing 1-legged Romanian deadlifts instead of conventional deadlifts.

The Safest Deadlift Technique

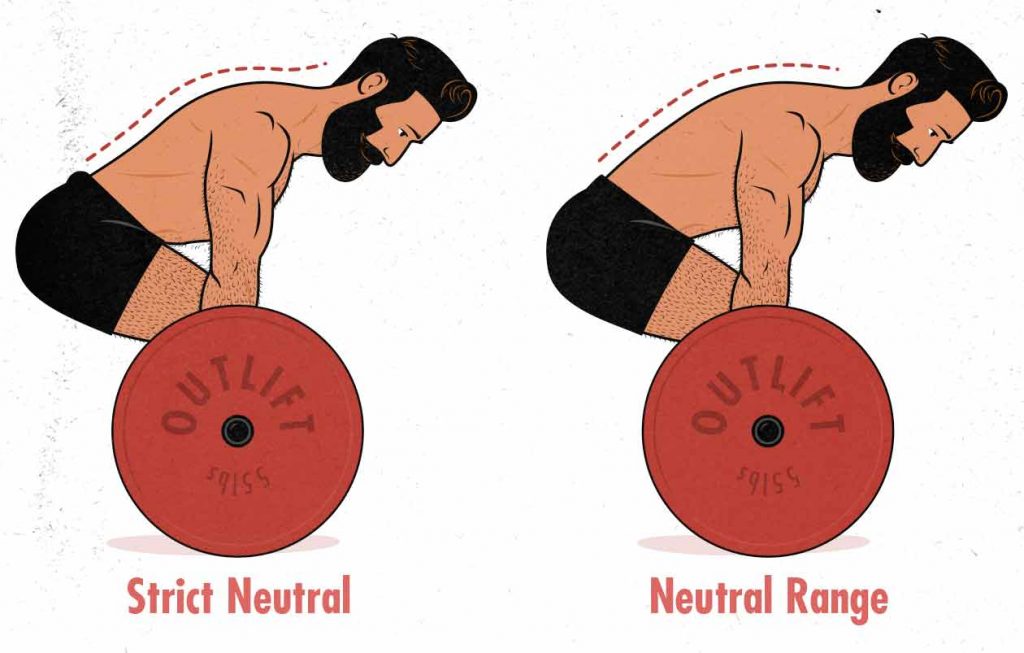

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. In order to minimize our risk of injury while reaping all these rewards, we need to deadlift with good technique. And different people have different ideas of what that looks like.

There are two popular ways of deadlifting (properly):

- Strongman-style: the strongman mentality is to build a back that’s tough even in unsafe positions, and so they deadlift hard and heavy. The barbell starts a bit higher, allowing for heavier loading. They use lifting straps, again allowing for heavier loading. And they allow hitching—resting the barbell on the knees and then dragging it up the thighs. You’ll also see strongmen lifting with rounded backs during a variety of different lifts, including deadlifts—on purpose.

- Powerlifter-style: the powerlifter mentality is to deadlift with absolutely textbook technique. They still deadlift heavy, of course, but the barbell starts low, there are no lifting straps, and there’s no hitching. This forces lighter weights, a longer range of motion, and a steadier amount of stress on the spine. All lifts are done with a neutral spine, and most especially deadlifts.

Dr Stuart McGill’s research found that deadlifting with a rounded back puts around 950% as much shear stress on our spines. No surprise, then, that strongmen have about twice the injury rate of powerlifters (source).

Most of us will want to deadlift more like powerlifters, keeping our spines in the neutral range. If we do that, we can expect a lower chance of getting injured than joggers, soccer players, and triathletes.

Building a Stronger Spine

We aren’t just trying to stay safe, though, we’re also trying to get bigger and stronger. And beyond the beginner stage, improving means that we need to push outside of our comfort zones and fight to add weight to the bar.

As we lift closer to our max weight, or as we near the end of a hard set, our textbook form will start to waver. If our back strength is our limiting factor, then our spinal erectors might stretch out a bit, and our backs might start to flex. That’s normal.

As we add weight to the bar, our spinal erectors will all grow strong together, and the stress on our backs will be shared between the many different vertebrae in our spines, minimizing the stress on any one joint.

The trick is that the curve must be modest and smooth. As long as we only flex a degree or two at each vertebra, we’re still within the neutral “range.” Our vertebrae are still in the middle of their range of motion. In this slightly flexed position, the shear stress should still be tolerable, and our risk of injury should stay low.

If we balance caution with aggression, our backs will grow bigger, stronger, harder, and more robust.

Why the Conventional Deadlift is Best for Building Muscle

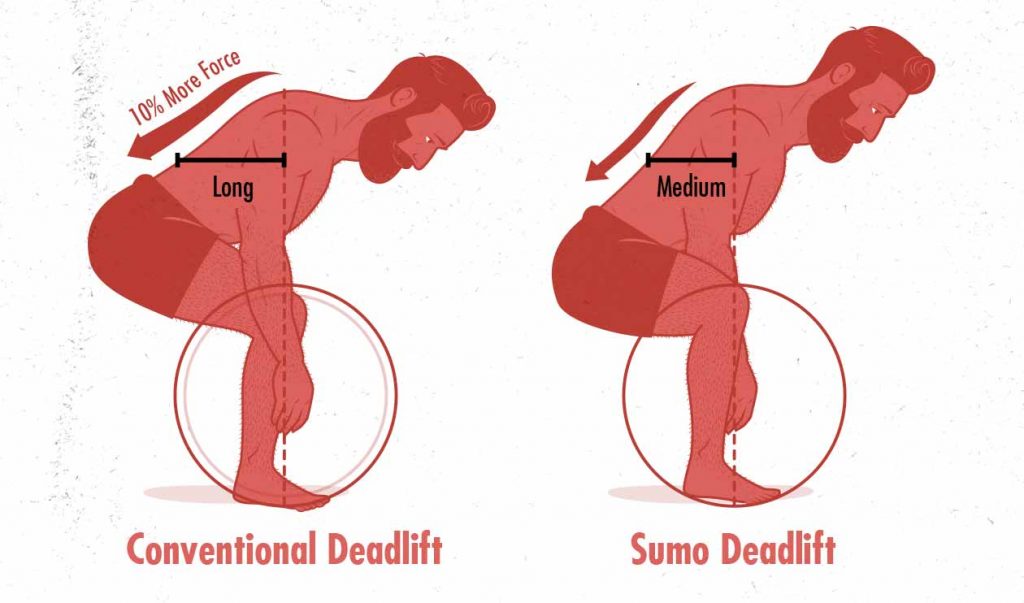

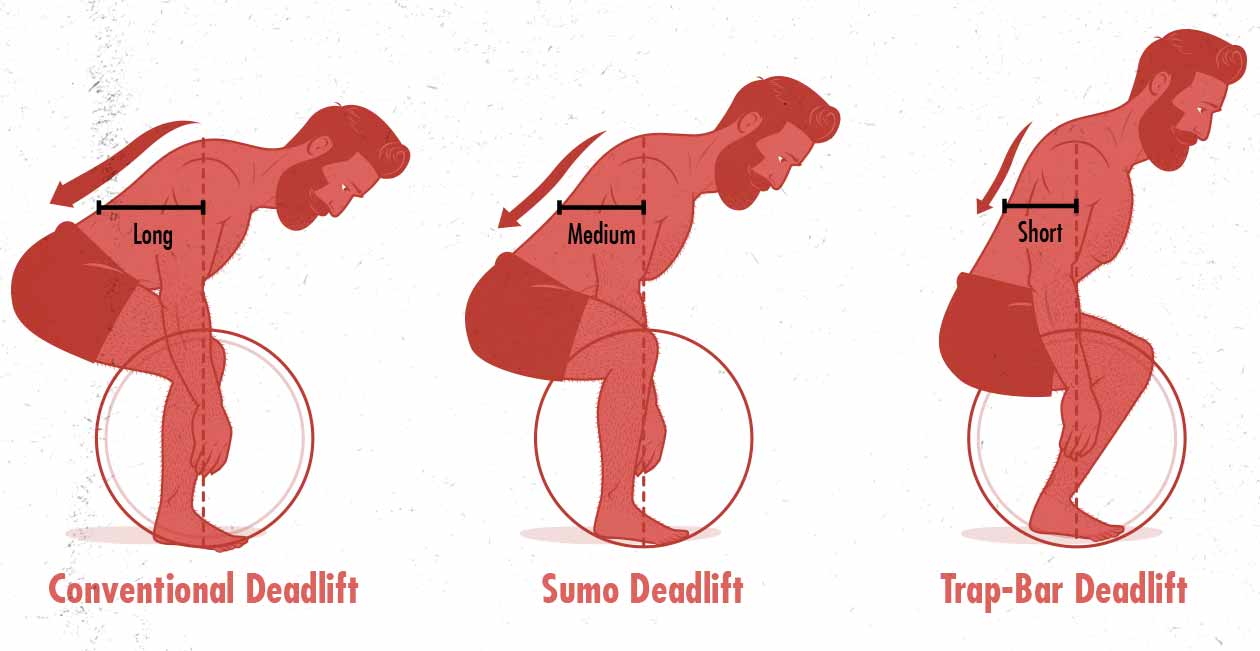

The conventional deadlift is the best variation for stimulating muscle growth. If you’re trying to bulk aggressively, or even leanly, it makes for a good default. To understand why that is, we have to look at the torso angle and moment arms:

A conventional deadlift has a more horizontal torso and a longer moment arm for our back muscles. Most studies find 8–10% more back stimulation from the conventional deadlift. It’s not a huge difference.

You need to lift the weight a greater distance, too, bringing your hips through a larger range of motion, and supporting the weight for longer. As a result, this study found conventional deadlifts used 25-40% more energy than sumo deadlifts.

Conventional deadlifts also allow for heavy loading. We don’t fail reps because we get tired of lifting the weight through a large range of motion; we fail because we’re not strong enough to get the weight past the sticking point. And at the sticking point, your back probably won’t limit you. That’s why most of us can deadlift similar amounts in both stances.

However, even though we’ll be lifting a comparable amount of weight, conventional deadlifts will almost certainly feel harder. That’s because they have a longer range of motion and remain more challenging throughout the entire range of motion. The peak stress per rep similar, but the average stress is greater, resulting in more muscle growth per rep. It has a better strength curve.

Getting that deeper range of motion in our hips is good, too. It maximally challenges our hips in the stretched position at the bottom of the lift, which is fairly ideal for muscle growth. Then, over the course of the rep, emphasis will shift from our lower backs (at the bottom) to our upper backs (at the top). And so we get great back development as well.

This is all to say that, as a rule of thumb, the conventional deadlift will leave us more winded and require longer rest times between sets. However, it will also do a better job of bulking up our hips and back, strengthening our spine, and improving our lifting fitness.

As a general rule of thumb, if you’re interested in size, general strength, fitness, and aesthetics, then go with the conventional deadlift.

Conventional Deadlift Alternatives

The Sumo Deadlift

The sumo deadlift is the most common alternative to the conventional deadlift. It’s harder on your quads and easier on your lower back. The range of motion is usually a bit shorter. Some people find it easier to get into the starting position. There’s no major downside.

Most people switch to sumo for the wrong reasons. They switch because when they deadlift conventional, they have a hard time keeping their back straight, their back gets too sore, or they feel the lift too much in their spinal erectors. Those are bad reasons to switch.

The conventional deadlift is largely a back exercise, so the fact that it challenges your back is hardly a sign that you should be doing a different variation. That would be like trading the bench press for triceps extensions because benching is hard on your chest. Just like the bench press is supposed to be hard on your chest, the conventional deadlift is supposed to be hard on your back.

Some say that if your back is having a hard time keeping up with the demands of the conventional deadlift, your back is identifying itself as a weak point that needs attention. So you should stick with the conventional deadlift, add in some back-dominant assistance and accessory lifts (like good mornings and barbell rows), and watch your back explode in size.

Being totally honest, though, sumo deadlifts are similar enough to conventional deadlifts that if you really do prefer them, it’s not going to ruin your results. They may not be technically ideal for gaining back size and strength, or for improving your aesthetics, but the difference won’t be bulk-breaking.

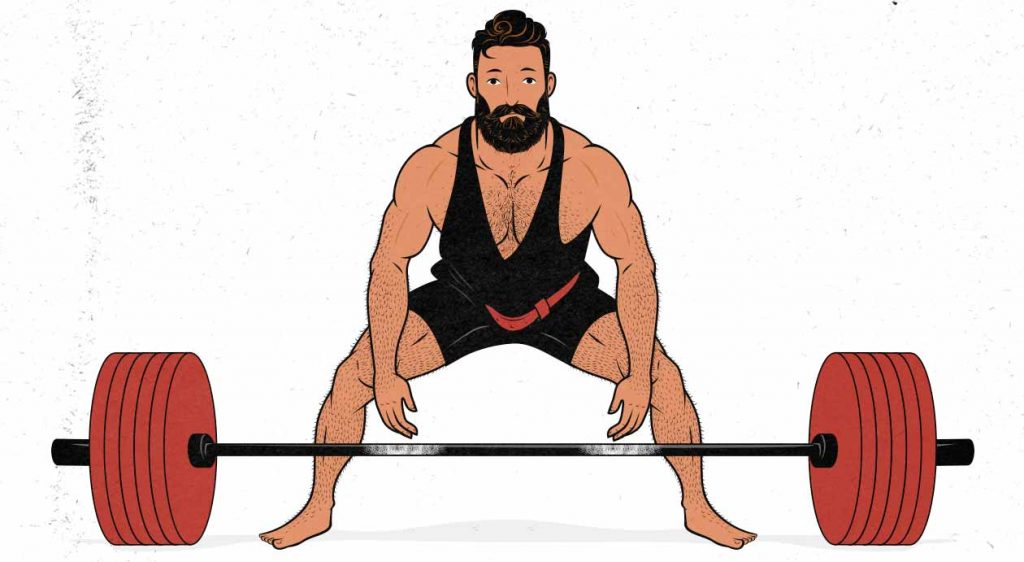

The Trap-Bar Deadlift

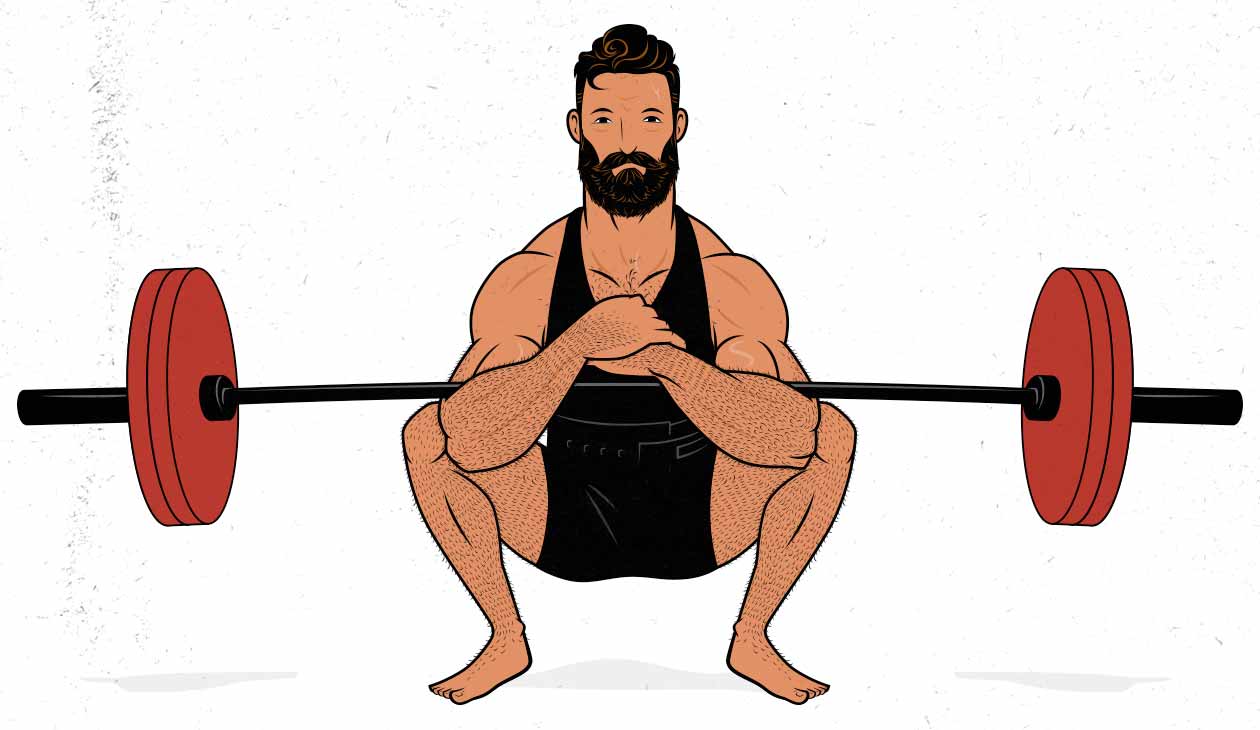

The trap-bar deadlift is perhaps the single best lift for building muscle and improving general strength. It’s a combination between a conventional deadlift, a farmer carry, and a squat:

- Like the conventional deadlift, you use a narrow stance. You can also sit back to create a hip-dominant lift, as you would doing a conventional deadlift.

- Like the farmer carry, you hold the weight out to your sides with a neutral grip. Furthermore, the trap bar is built so the handles won’t be trying to rotate out of your hands, making it much easier to hold onto than a barbell. This means you won’t need to be as finicky about using a mixed grip, hook grip, or chalk.

- Like the squat, because there isn’t a barbell in the way, your knees are free to track forward, allowing you to lift the weight up with your quads. It’s also easier on your lower back because you can keep your torso more upright.

As a result, the trap-bar deadlift is an amazing lift for overall strength development. It’s great for our posterior chains and for our quads. However, the trap bar deadlift isn’t as good for our hamstrings, backs, or forearms as the conventional deadlift, and we already have the squat for our quads.

Furthermore, because the handles are raised higher, the trap-bar deadlift uses the smallest range of motion of all deadlifts. A smaller range of motion isn’t always a bad thing. It depends on what we’re trying to accomplish. But in this case, that smaller range of motion is likely to reduce the muscle growth that we stimulate. It might also make trap-bar deadlifts worse for improving our work capacity, which is one of the great strengths of the conventional deadlift.

So although the trap bar deadlift is arguably the best all-around lower-body lift, you’ll probably get more back for your buck by doing conventional deadlifts and front squats instead.

Unless, of course, you do a trap-bar deadlift as if it were a conventional deadlift. After all, there’s nothing stopping you from getting a trap bar with shorter handles, sitting back further into your starting position, and then muscling the weight up your posterior chain. At that point, you’re essentially doing a conventional deadlift but with a trap bar.

If you use a conventional deadlift technique with a trap bar, you’ll get some cool advantages, too:

- You’ll be able to hold your arms in a more neutral position, which is nice on the shoulders.

- Your grip will be wider, which is great for your traps.

- You won’t need to worry about fancy grip techniques or chalk to stop the bar from rolling out of your hands.

If you’re doing a conventional-style deadlift but with a trap bar, I’d still count that as a conventional deadlift. You’ll still get all of the benefits.

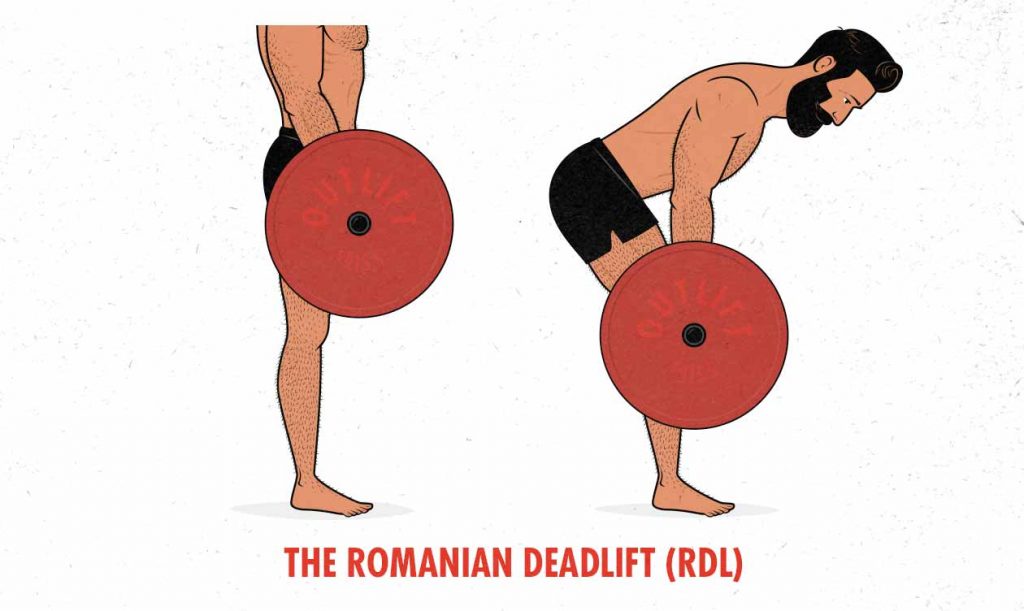

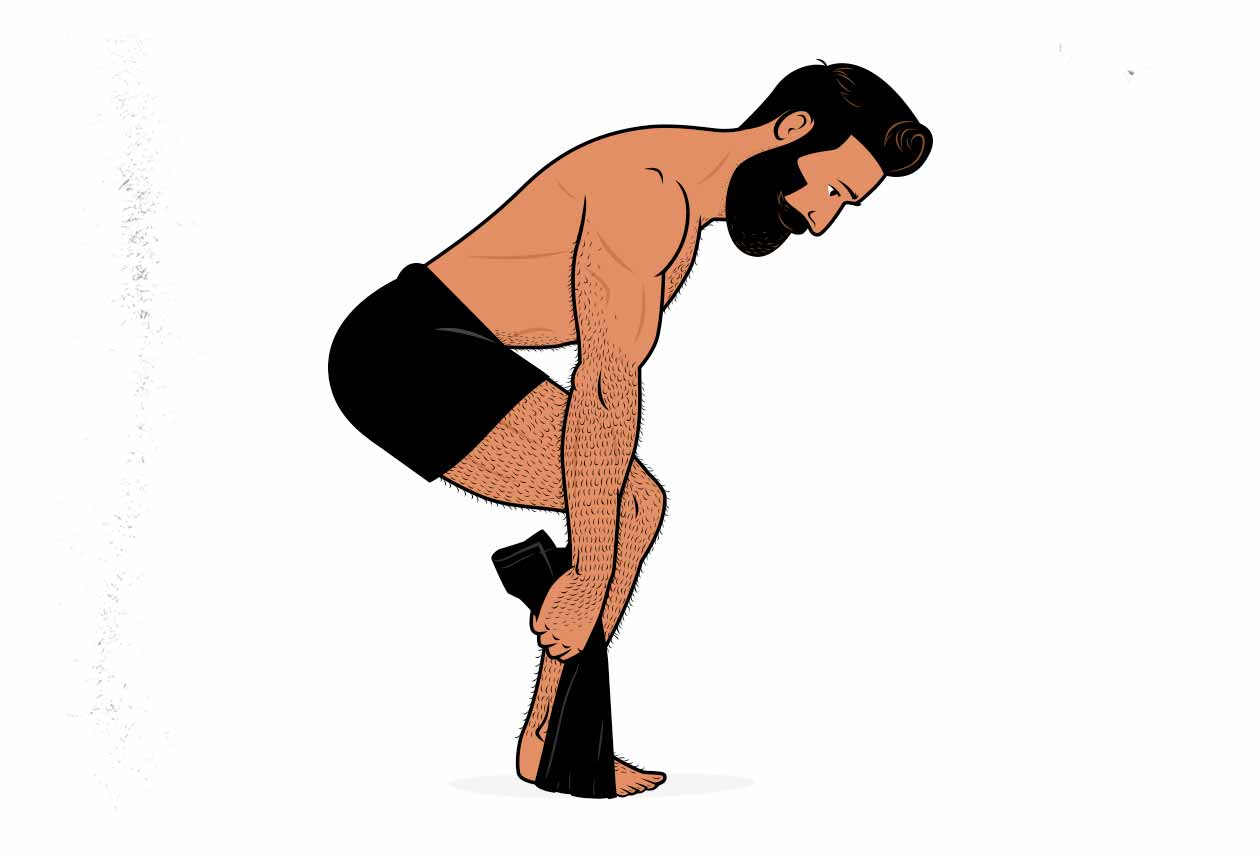

The Romanian Deadlift

Romanian deadlifts are the top half of a conventional deadlift, and they start from a standing position. You lower the barbell to your knees, then drive the barbell back up with your hips, like so:

Since you aren’t lowering the barbell to the floor, it also keeps your torso in a more upright position, reducing the demands on your lower back, both in terms of peak load (bottom of the lift) and average load (over the full range of motion):

Combine that with the fact that Romanian deadlifts are substantially lighter than full deadlifts, and we have a much less fatiguing lift that’s still similarly good at packing meat onto our hips and hamstrings.

Mind, most people want to use the deadlift to bulk up their upper bodies and harden their bones. The Romanian deadlift isn’t quite as good for that. We normally use them as an assistance lift instead of the main lift. But if none of the heavy deadlift variations work well for you, the Romanian deadlift is a great fall-back lift.

Bodyweight Deadlift Alternatives

Finding good bodyweight alternatives to deadlifts is tricky because some of the main benefits of deadlifts come from the heavy load on our spines, traps, and spinal erectors. So the downside is that without heavy weights, we won’t be able to put much stress on our spines or stimulate much growth in our traps or spinal erectors. Still, there are a few bodyweight deadlift variations that are great for building muscle in our hamstrings and glutes:

- Bodyweight towel deadlift

- One-legged Romanian deadlift

- One-legged hip thrust

- Straight-legged bridges

Anything that challenges the strength or work capacity of our muscles can provoke muscle growth. However, we need to keep the hypertrophy principles in mind when trying to build muscle with bodyweight training:

- We should still lift in moderate rep ranges (of 5–40 reps per set): if we’re doing more than twenty reps per set, our pain tolerance can become a limiting factor instead of our muscle strength. And if we’re doing more than forty reps per set, we’ll be making improvements to our endurance instead of to our muscular size and strength.

- We need to make sure that balance isn’t the limiting factor: if we’re concentrating more on keeping our balance than on working our muscles, we won’t be limited by our strength, and so we won’t provoke muscle growth.

- We need to lift close to muscular failure: when we’re deadlifting in moderate rep ranges of 4–10, our muscles often give out before the set becomes overly tiring or painful. With bodyweight training, though, because the rep ranges can be so high, we’re more likely to stop our sets because we’re tired or in pain. To ensure that we’re stimulating muscle growth, we need to endure all the way until our muscles start to give out.

- We should try to challenge our muscles in a stretched position: one of the reasons the deadlift is so great at stimulating muscle hypertrophy is that it challenges our glutes and hamstrings in a stretched position at the bottom of the lift.

So when it comes to choosing bodyweight variations, we need to find bodyweight variations that are heavy enough to cause muscle failure before forty reps and ideally before twenty reps. We also need to ensure the lift is sturdy enough that our balance doesn’t limit us (which can be a problem with one-legged deadlifts). And we want to challenge our muscles in the deep part of the range of motion. But if we can do that, we can do a great job of bulking up our hamstrings and glutes.

The easiest way to make bodyweight deadlifts heavier is to train one leg at a time (unilaterally). If we can do forty glute bridges in a row, we may only be able to do twenty one-legged glute bridges (per side). As a result, the best bodyweight deadlift variations tend to be one-legged.

The Bodyweight Towel Deadlift

Most bodyweight deadlift alternatives don’t let us lift in heavier rep ranges, they don’t challenge our glutes and hamstrings in a stretched position, and they don’t work our spinal erectors or traps. The towel deadlift solves all of those problems, allowing us to bulk up our posterior chain with just a towel.

The towel deadlift is done by standing on a towel and pulling on it, just like we’d pull on a barbell. The difference is that this is an isometric lift—no range of motion. No matter how hard you pull on the towel, it will not move. We’re locked in the bottom position. And that’s okay.

If we look at a recent meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of isometrics for muscle hypertrophy, we see that isometrics that challenge our muscles in a stretched position are actually quite good at stimulating muscle growth. This deadlift variation maximally challenges our hips and hamstrings in a stretched position, so we can expect it to be quite good for stimulating muscle growth. And since we can grip the towel at any height, we can intentionally set up with a maximal stretch on our hamstrings.

The other great thing about the towel deadlift is that our entire posterior chain is engaged. As we pull on the towel, our spinal erectors and mid-back muscles need to work just as hard as pulling on a too-heavy barbell. It’s a true full-body lift.

To do towel deadlifts, we recommend using burst reps. Pull as hard as you can for a few seconds. That’s your first rep. Then pull as hard as you can for another few seconds. That’s your second rep. You can progress how many seconds you pull for, and you can adjust how many reps you do per set. For example:

- Week One: 3 sets of 3 reps (3×3), and each rep lasts five seconds.

- Week Two: 4 sets of 3 reps (4×3), and each rep lasts six seconds.

- Week Three: 4 sets of 4 reps (4×4), and each reps lasts seven seconds.

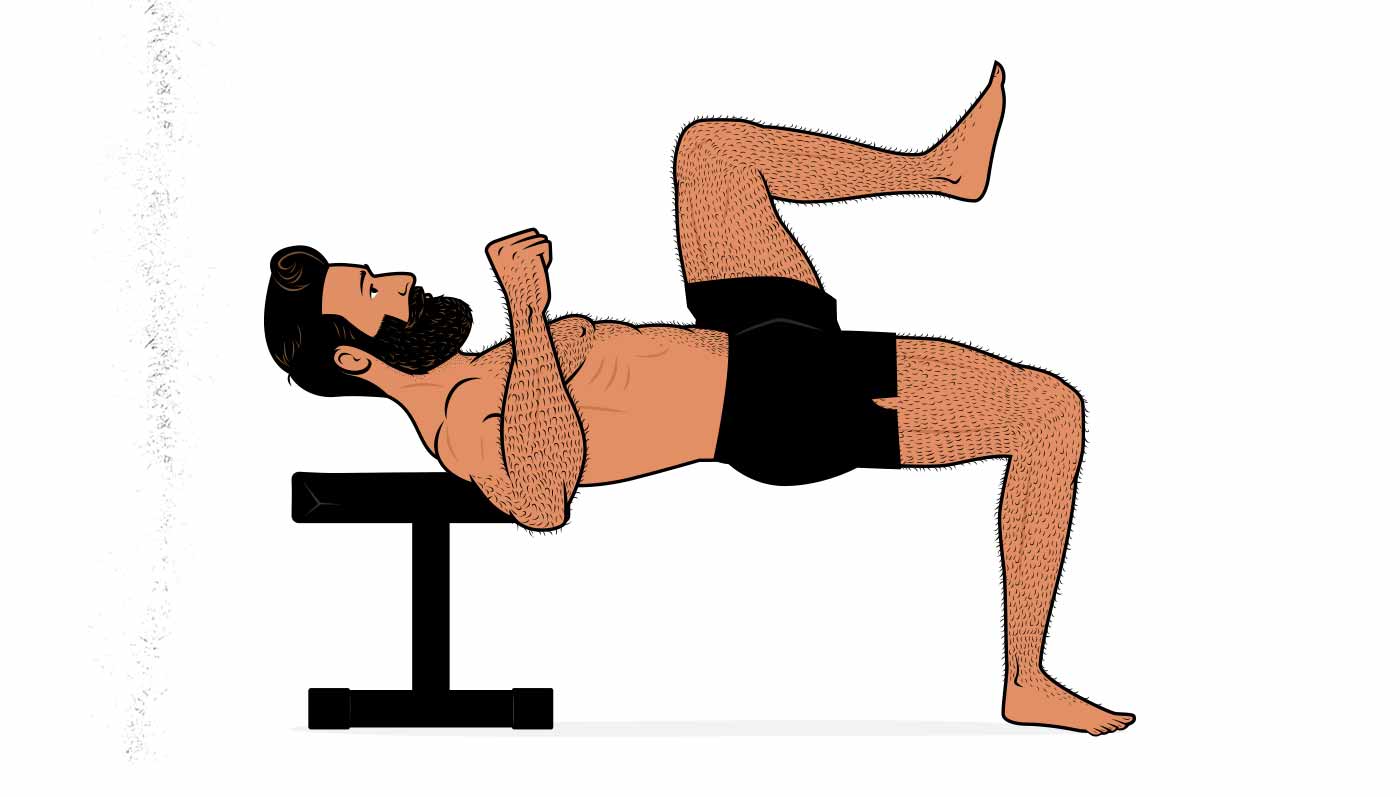

The Hip Thrust

Hip thrusts are an okay lift for gaining size and strength in our glutes, and our hamstrings will get some stimulus as well. The problem is that the hip thrust is easy at the bottom, when our muscles are stretched, and hard at the top, where our muscles are contracted. That’s the worst strength curve for building muscle. It doesn’t make the lift useless, but it is a poor choice as our main lift. It’s better used as a lighter accessory lift for the glutes.

There are a few hip thrust variations of varying difficulty:

- Glute Bridge: start with regular glute bridges until you can do at least twenty reps, but feel free to stick with it until you can get as many as forty.

- One-Legged Glute Bridge: once you can do 20–40 reps with both legs on the ground, switch to single-leg variations and work your way back up to 20–40 reps.

- Hip Thrust: when you can do 20–40 reps of one-legged glute bridges, switch to doing hip thrusts with your back on a bench. Feel free to put a book-filled bag in your lap to make the lift harder.

- One-Legged Hip Thrust: When you can do 20–40 reps, switch to using a single leg at a time, and work your way back up to forty reps.

So, overall, if your main goal is to bulk up just your hips, the hip thrust can be a reasonable bodyweight alternative to the deadlift.

How to Increase Your Deadlift Strength

The best way to increase your deadlift strength is to do the deadlift every week, using it build muscle. The areas holding you back will be brought closest to failure, they’ll get the greatest growth stimulus, and they’ll grow bigger and stronger.

However, it can also help to pay attention to which muscles are holding you back, limiting your strength. If you can identify the areas that are limiting you, you can use assistance and accessory lifts to intentionally target those areas, building even more muscle and increasing your deadlift strength even faster. And since the deadlift can be so fatiguing, using smaller lifts to work on your limiting factors can save you a lot of time and energy. It’s much easier than simply doing more deadlifts.

Diagnosing Weak Links

There are a few different limiting factors that are common on the deadlift, and the solution isn’t always intuitive. For example, if your lower back rounds, it might not be because you have a weak lower back but because of weak hips. So let’s tackle the common limiting factors one by one:

- You can’t break the bar off the floor.

- You fail with the bar a few inches off the ground.

- The bar slips out of your hands.

- Failing above the knee.

- Your back rounds.

The Bar Won’t Move

If the bar won’t move, it might be because you’re using a weight that’s much too heavy. In this case, choose a slightly lower weight. No problem.

Another reason the barbell gets stuck on the floor is that our quads are disproportionately weak. Conventional deadlifts mainly train our hips and back, so it’s rare for our quads to be a limiting factor, but it can happen. With sumo and trap-bar deadlifts, though, the quads play a bigger role, so it’s common for the barbell to get stuck on the floor because of weak quads.

The solution here is to do more squatting. Front squats and Zercher squats are a good choice because they’ll sneak in some bonus upper-back growth.

Your hips are too weak. If you’re deadlifting with a conventional stance, your back is holding a proper position, but you can’t get the bar to move; it’s probably because your hips are too weak. Romanian deadlifts, low-bar good mornings, and hip thrusts will help.

Failing a Few Inches Off the Ground

This is the ideal scenario. This means that your muscles are proportionately developed; they just aren’t quite strong enough yet.

In this case, you don’t need to do anything special. Just keep growing stronger at the overall movement pattern. Conventional deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, barbell rows, and front-loaded squats are all great.

Grip Issues While Deadlifting

Use a strong grip technique. The first thing is to ensure you’re using a mixed or hook grip, which will help keep the barbell from rolling out of your grip.

The mixed grip is how powerlifters grip the bar. It will increase biceps activation on the underhand side, so if you switch your grip between sets, that can add a bit of biceps work into your routine. It also increases the risk of tearing your biceps, but that’s quite rare, and it mainly happens to powerlifters who are maxing out in competitions. You can also radically reduce your risk of tearing your biceps by keeping your upper arms more relaxed while deadlifting (which you should be doing anyway).

The hook grip is how weightlifters grip the bar. It will allow you to deadlift more symmetrically, which makes deadlifting with good technique a bit easier, and it also keeps your spine from twisting. However, it’s also the more painful way of gripping the barbell. While learning it, my thumbs were torn and purple for a good few months. But it’s the strongest and most versatile way to grip a barbell, and I dig it.

Add friction to your hands. Once you’re using a strong grip, the next thing to solve is the sweatiness and slipperiness. Try using chalk (for any grip) or putting some lifting tape around your thumb (for the hook grip). Combined with good grip technique, this will often be enough.

If you train at a commercial gym, they might not allow chalk. That’s not the end of the world. You’ll just need to get your grip extra strong (or switch to a hook grip with thumb tape).

Strengthen your grip. If you’re using good technique and chalk/tape, and you’re still having trouble holding onto the bar, then the next thing to do is to strengthen your grip.

If the barbell is slipping out of your hands while deadlifting, then it means that you lack the strength to keep your hands closed. Duh, I know. But this is a specific type of grip strength called support strength, which is different from the type of strength that you use while squeezing things (crushing strength). As a result, it requires a specific type of training.

How to Strengthen Your Deadlift Grip

There are a few good ways to strengthen your grip, starting with the simplest:

- Follow a program that uses a variety of barbell lifts. Barbell rows, Romanian deadlifts, chin-ups, farmer carries, and curls will all help to strengthen your grip. If you have enough of these in your program, you probably won’t ever need dedicated grip training. But if your grip has fallen behind, it may pay to emphasize it for a bit.

- Static holds. Once you’ve finished your heavy lifting for the day, load up a barbell and hold onto it for 15–30 seconds. Do 2–4 sets of these. Whenever you’re able to hold the bar for a good 30 seconds on the final set, add a bit more weight to the bar next workout. Use the same grip that you prefer while deadlifting (mixed or hook grip).

- One-armed static holds. If you want to mix in some core training with your grip training, you can train your grip one hand at a time. This is great for your obliques. (This works best if you’re using a barbell that has centre knurling.)

- Weighted hangs. If your back is fatigued from your heavy lifting, you might prefer to hang from a chin-up bar instead. It won’t be quite as specific, and you’ll need to use a double-underhand grip, but it will allow you to train your grip without further stressing your back. Again, do these at the very end of your workouts. And again, hold the bar for 15–30 seconds, adding weight when you can hold the bar for 30 seconds.

The trick is to grip a bar that has a similar diameter to the barbell that you’re deadlifting with. You can indeed emphasize your grip by using handles with a thicker diameter, but the strength that you gain won’t transfer over to the deadlift as well.

Lifting straps. You could, of course, avoid all of this hassle by using lifting straps, which is the approach that strongmen take. You’d miss out on strengthening your grip muscles when deadlifting, but it’s an option. And if you find that they save you time and hassle, they may even be a worthwhile option.

Failing Above the Knee

Failing above the knee is usually a back rounding issue. Take a video of yourself deadlifting and see if your back is falling out of the neutral range. If you notice that your back is rounding, see the back rounding section below.

If your back is holding a good position but you’re still having trouble locking out the deadlift, then we need to get your hips stronger at that top part of the lift. Glute bridges and hip thrusts are good for training hip lockout strength.

Back Rounding

There are a couple of reasons why your back rounds while deadlifting.

First, you don’t have the mobility to get into the starting position. That might be something you can work on, or maybe those are just the hips you were born with. In either case, that’s fine, you can just raise the barbell up to the point where you can deadlift without rounding your back. Switching to a trap bar can also be a good solution to this problem.

Second, your hips aren’t strong enough. As we covered earlier, rounding your back while deadlifting opens up your hip angle while scooching them closer to the barbell, giving your hips better leverage.

The first downside is that this makes the deadlift more dangerous, and the second downside is that you’ll have a harder time locking the bar out. (When people fail above the knees, deadlifting with a round back is usually the root problem.)

If this is happening, you’ll want to strengthen your hips with Romanian deadlifts, glute-ham raises, glute bridges, or hip thrusts.

Third, your spinal erectors aren’t strong enough. The conventional deadlift is a back exercise, so it’s totally normal for your back to give out first. When you notice that your back starts to flex (or if you feel that it’s about to start flexing) more than a few degrees, that’s a good reason to end your set. Your back has gotten what it needs out of the lift.

To continue strengthening your back, you could simply do more conventional deadlifts. After all, if you’re failing due to your back strength, then your back is getting the largest growth stimulus out of your deadlifts. But if you’re failing on your back, chances are that your back is already way too fatigued to handle any extra deadlifting volume.

A better way to strengthen your back is to choose lighter and easier exercises that will bulk up your back muscles without fatiguing you quite as much. High-bar good mornings, barbell rows, front-loaded squats, and hyper-extensions will help.

The Best Deadlift Assistance Lifts

Heavy conventional deadlifts are incredibly fatiguing, especially once you get strong at them, and especially if you’re pushing yourself hard. Most people find deadlifts about twice as fatiguing as heavy squatting. And so, not surprisingly, most people can only handle deadlifting about once per week.

Deadlifting more than once per week tends to be too hard on our spinal discs, too stressful for our spinal erectors, and put too much wear and tear on our hands. And it’s just tiring. Nobody wants to feel like a puddle all week long.

However, training a movement pattern once a week isn’t ideal for gaining muscle or strength. That means that if we want to bring our frequency up into the ideal range (2–3 times per week), we should turn to assistance and accessory lifts. They can help us bulk the relevant muscles without accumulating too much overall fatigue.

The next thing we need to consider is whether your spinal erectors need more work or less work.

- The case for more spinal erector work. Spending extra time bulking up your spinal erectors will make deadlifts less stressful on your back, allowing you to either feel fresher or to handle higher deadlift volumes. In this case, you might benefit from barbell rows, good mornings, and hyperextensions.

- The case for less spinal erector work. On the other hand, if your spinal erectors are already being pushed to their limits, you might want to take it easy during the rest of the week. You might want to choose lifts that minimize the role of your spinal erectors, giving them more time to recover.

The best approach is probably to do a bit of both. Choose a few lifts that will strengthen your spinal erectors that aren’t overly stressful. And then shy away from lifts that cause too much fatigue in your lower back.

Another technique is to deadlift with a lower volume but to increase the volume of your assistance lifts. For example, maybe you do 4–5 sets of squats but just three sets of deadlifts. Then, to make up for that disparity, you include more rowing and Romanian deadlifts, fewer squat accessories.

Finally, if you’re ever feeling beat up before a session of heavy deadlifts, consider swapping in an assistance lift instead. If your lower back is already feeling tired before you even start your conventional deadlifts, consider doing Romanian deadlifts instead. They’ll be a bit easier on your back and will hopefully leave you feeling fresher for the next week.

The 1-Legged Romanian Deadlift

The trick with choosing deadlift assistance exercises is that we want to manage the stress on our backs. We want to stimulate our spinal erectors as much as possible without accumulating more stress than they can recover from. We also want to keep the stress on our spinal discs manageable.

One tool for this is 1-legged Romanian deadlifts. By training our legs one at a time, we can get just as much stimulation on our hips and hamstrings while using much lighter weights. Our spinal erectors still get worked, of course, but with substantially lighter weights and for twice as many sets. This may even act as a form of active recovery, allowing them to heal and adapt more quickly.

The same is true for our forearms. We’re holding much less weight but for twice as many sets, which seems to be great for managing fatigue and recovery.

The Wide-Grip Deadlift

Using a wider grip while deadlift does a couple of cool things. First, it forces you to bend further over, extending the range of motion for your hips. Second, it puts your back in a more horizontal position, making the lift better for strengthening your spinal erectors. Third, it puts almost all of your upper back muscles into a difficult position, forcing them to work much harder.

Now, all of this will force you to use lighter weights. As a result, using a snatch-grip isn’t necessarily better than the deadlift for stimulating overall muscle growth. However, it’s a great way to get a ton of muscle growth out of lighter weights, making it a great assistance lift.

I would turn to the snatch-grip deadlift if you want to speed up your upper-back development. If you wanted bigger traps, this would be a great assistance lift.

Now, there’s a popular type of wide-grip deadlift called the snatch-grip deadlift. That’s a great variation typically used to improve Olympic weightlifting performance. Thing is, snatch-grip deadlifts are done with a very wide grip. That might extend the range of motion by more than you can handle. Or maybe not. Feel free to try them. Remember that you’re free to use a comfortably wide grip width. I like to put my pinky fingers on the bench press knurl marks.

The Front Squat / Zercher Squat

Back squats work many of the same muscles used in the deadlift, including the quads, glutes, spinal erectors, and lats. However, some experts, such as Greg Nuckols, MA, believe that the strength you gain while doing back squats translates poorly to deadlift strength. His reasoning is that your limiting factors on the squat are too different from the deadlift.

For example, let’s say that your quads are your limiting muscle group on your back squat, and your spinal erectors are your limiting muscle group on your deadlift. When squatting, your spinal erectors are more than strong enough, so they won’t grow. It’s your quads that will grow.

Then, when you go back to deadlifts, sure, you’ll have stronger quads, but those were never holding back your deadlift. Your limiting factor on the deadlift is still your spinal erectors; the squats haven’t stimulated any growth there.

However, not all squats are the same. Some squat variations demand much more from your spinal erectors than others. That’s where front-loaded squats come in. As we covered in our squat article, front squats are just as good for your upper back as for your quads, making them brilliant accessory lifts for the deadlift.

The added benefit here, of course, is that spending more time squatting will also help to improve your squat.

The Best Deadlift Accessory Lifts

Barbell Rows

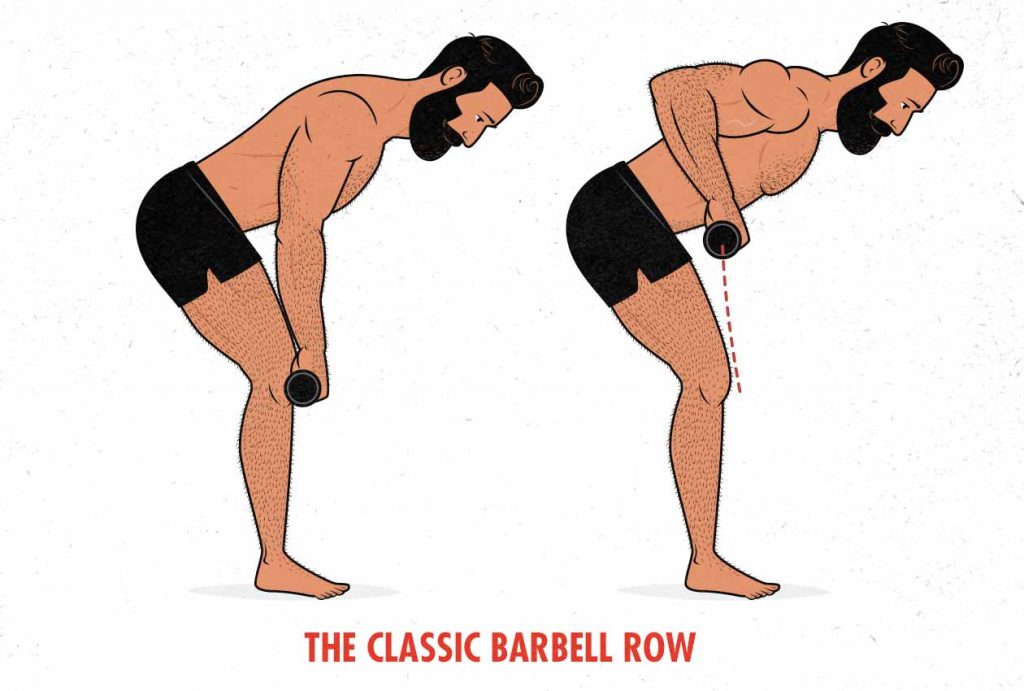

Barbells rows are similar to deadlifts. They work the same muscles: your grip, spinal erectors, glutes, and hamstrings. The difference is that the deadlift moves with the hips, supports with the back, whereas the row moves with the back, supports with the hips.

Because lifting a weight yields more muscle growth than stabilizing a weight, the barbell row tends to be better at training your upper back, whereas the deadlift is better for developing the spinal erectors and hips. For overall muscle growth, do both.

The classic barbell row, where you stand in a Romanian deadlift position (barbell at the knees) and then row the barbell to your belly button or sternum, is a good default choice. It’s a fairly easy lift that’s great for bulking up your lats and forearms.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that barbell rows train the lats, but don’t let that fool you. The lats don’t connect the vertebrae in our spines, so they won’t help us maintain our spinal position while deadlifting. What gives barbell rows such great carryover to deadlifts is that they’ll also bulk up our spinal erectors and hips. That means choosing chest-supported or arm-supported rows, where your hips and spinal erectors are removed, won’t cut it. Those are accessory lifts for the chin-up.

That also means that choosing row variations that emphasize the hips and spinal erectors can have even more transference to the deadlift, provided your back isn’t too fatigued already.

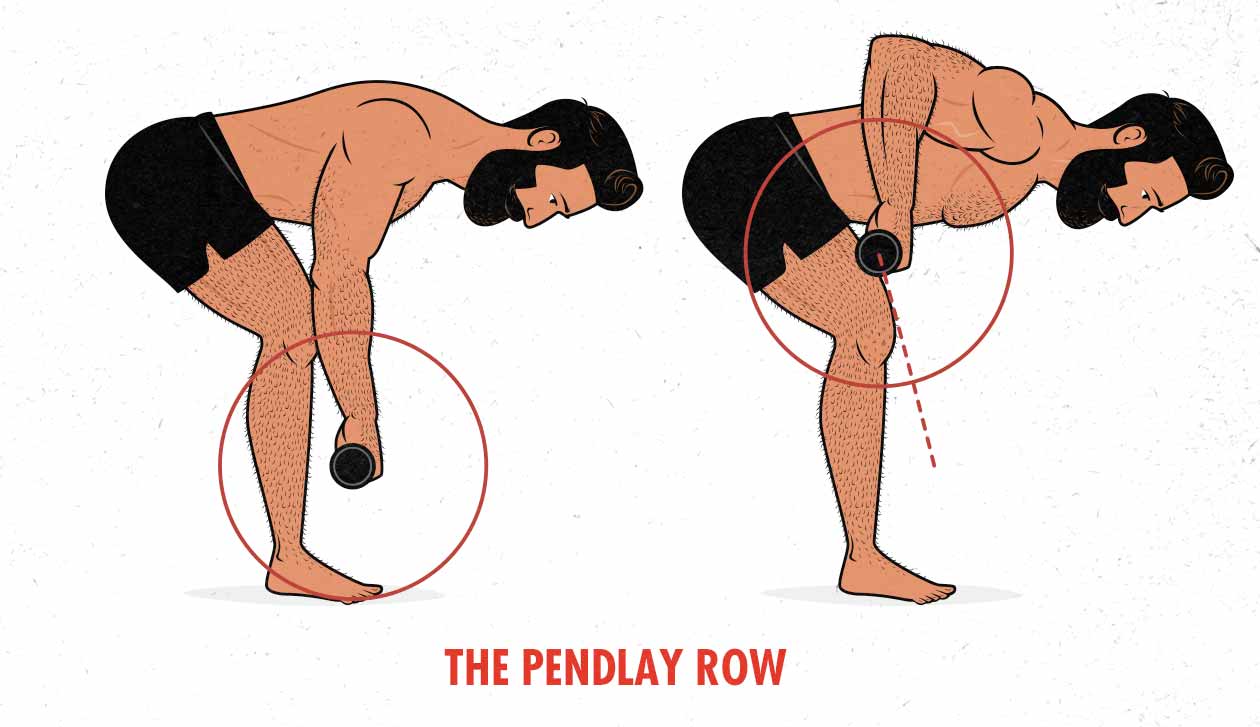

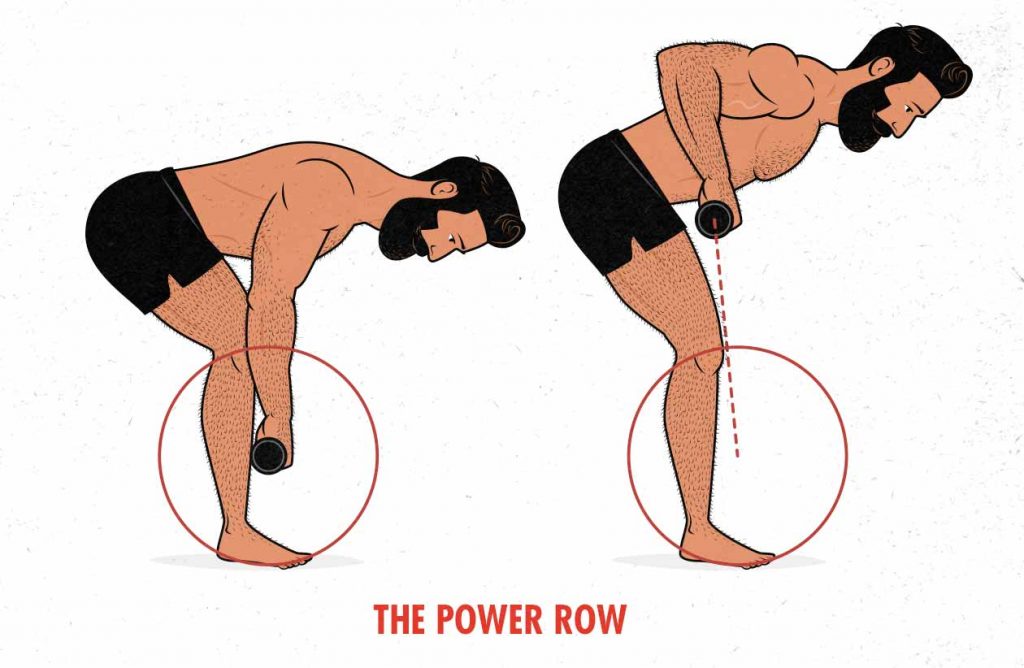

If we deadlift from the floor instead of our knees, that shoots our hips further back and puts our backs in a more horizontal position, like so:

What we’re seeing here is that rowing from our knees (left) is pretty easy on our hips and spinal erectors. As a result, our lats and forearms are more likely to be our limiting factor, so they’ll get more of the growth stimulus. When we row from the floor, it’s around 30% harder on our hips and spinal erectors, making it more likely that they’ll limit our performance and thus see more growth.

The exact effects vary from person to person, of course, but rowing from the knees puts more emphasis on the lats and upper back, whereas rowing from the floor puts more emphasis on the lower back.

That brings us to the more advanced rowing variations:

The Pendlay row starts with the barbell on the ground and finishes when the barbell touches your torso. There’s no hip drive, so you finish with your hips in the same position, your back at the same angle. This is a great lift for bulking up your spinal erectors; just make sure you aren’t overdoing it. If you do a lot of heavy barbell work, it’s easy to overwork them.

The power row adds hip drive into the Pendlay row. The obvious benefit is that you’ll be working your glutes and hamstrings harder. The subtler benefit is that you’ll also be building momentum through the bottom part of the lift. That momentum will help your lats blast through the sticking point at the top. That means that you’ll be able to use a heavier weight or get more reps, giving your upper back even more stimulation.

This row variation has the most carryover to your deadlift, and it’s a favourite among top-level powerlifters (such as Cailer Woolam). The downside is that it’s a big lift—especially for an accessory. Again, you need to make sure that your back is tough enough to weather the onslaught.

Glute Bridges / Hip Thrusts

Glute bridges and hip thrusts are a great way to bulk up your hips without putting any more stress on your back or hands. They’re hardest at the lockout position, so they’re especially good for improving lockout strength, but the size you gain will improve your hip strength in every part of the deadlift.

Glute bridges use a smaller range of motion but they’re easier to set up and can be loaded heavier. They’re a good lift to start with.

Hip thrusts are a bit more finicky but they use a much larger range of motion and so they technically do a better job of stimulating the glutes.

Back Raises / Reverse Hypers

If you want to improve your back extension strength, these are the lift for you. They’ll strengthen your spinal erectors while simultaneously training your hips. The only downside is that you’ll need a special machine, which brings us to…

Good Mornings

Good mornings got their name because they resemble the movement we do when we get out of bed in the morning. Another source claims that they got their name because they look like the movement that we use to wish people a good morning.

I felt ashamed when I learned that. I hadn’t known. I had to completely change how I got out of bed and said good morning to my wife. She was confused at first, but I think it’s been good for our marriage.

Anyway, if you want a simple solution to back troubles on the deadlift, good mornings are for you. They’re great for strengthening your spinal erectors, hamstrings, and back-extension strength. Best of all, they don’t require any special equipment, they’re easy to set up, dead simple to learn, and they’re a breeze to recover from.

If you train at home with a simple barbell home gym, good mornings are a good barbell alternative to reverse hypers, back raises, and even glute-ham raises. (And they’re a perfectly good lift by their own right.)

Low-bar vs high-bar: good mornings can be done with the barbell in either a low-bar or high-bar position. The low-bar position is easier on your back and allows for heavier weights, making it good for training back extension with a tired back. The high-bar position is harder on your back but uses lighter weights, making it great for improving back strength.

Safety: if you already know how to squat and deadlift, then good mornings shouldn’t really be very dangerous. Still, you should probably use safety bars (as you would when squatting), and this isn’t really an exercise that you’ll want to take to failure.

How Much Should You Be Able to Deadlift?

Most strength standards come from powerlifting stats, but powerlifting tends to draw people who are naturally strong, only the strongest of them stick with it, and they devote a third of their training to improving their deadlift strength. Plus, many of them use PEDs. That can inflate the common strength standards.

So, we surveyed 540 people from our newsletter:

- Most thin beginners start off deadlifting less than 135 pounds, especially when doing sets of 4–8 reps. If you can’t deadlift 135 pounds yet, it’s often better to start with Romanian deadlifts.

- After one year of training, most guys can deadlift around 185 pounds for a few reps. Some guys can deadlift as much as three plates (315 pounds).

- After three years of training, most guys can deadlift 225–315 pounds for a few reps. Less than 5% of guys can deadlift four plates (405 pounds). A few guys could deadlift 495 pounds.

- After 5–10 years of lifting weights, 12% of guys could deadlift four plates. 495 pounds was still incredibly rare.

A 315-pound deadlift is slightly better than average for a lifetime lifter, especially if you can lift it for a few reps.

A 405-pound deadlift is incredibly good. You’ll be stronger than almost 90% of lifetime lifters.

A 495-pound deadlift is extremely rare. Fewer than 5% of lifters ever get there. It’s relatively common among lifetime powerlifters, though, especially in the heavier weight classes.

For more on strength standards, we have an article on how much the average man can lift.

Summary

The deadlift is perhaps the single best lift for becoming bigger, stronger and better looking. It can help us live a longer and healthier life, too. But as great as the deadlift is, and as efficient as it is per set, it’s also incredibly fatiguing. As a result, we need to program it sparingly. Less is more.

When taking a lower-volume approach to deadlifting, it pays to include plenty of assistance and accessory lifts. That allows us to boost the volume and frequency back up into the ideal range without accumulating as much fatigue. It also gives our spines a chance to more fully recover between heavy deadlifting sessions.

Of the assistance lifts, Romanian deadlifts are perhaps the best all-around choice. If they’re too tiring on your lower back or grip, try doing them one leg at a time.

Of the accessory lifts, nothing beats the barbell row. But if that’s too ambitious, back extensions or good mornings are an easy way to strengthen your spinal erectors without accumulating much extra fatigue.

Finally, you may have an easier time progressing on the deadlift if you include some front-loaded squats in your program, such as front squats and Zercher squats.

If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. We also have our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program and Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program for beginners. If you liked this article, I think you’d love our full programs.

Quick question – you mention that the RDL is a lighter lift than the deadlift and I’m wondering why this is necessarily so. I find getting the weight from the ground to mid-shin to be by far the hardest part of the deadlift and can generally lift about the same (about 210lb) for both lifts, but can do the RDL for more reps. Never tried for a heavy single for either lift.

One reason why Romanian deadlifts are usually lighter is simply that people tend to program them that way. You’ll often find guys doing deadlifts for sets of 1–5 and then doing Romanian deadlifts for sets of 8–15. There’s good reason for that, too. Deadlifts become incredibly taxing on the cardiovascular system (and grip) in higher rep ranges, and there’s a fear of Romanian deadlifts being more dangerous in the lower rep ranges. I don’t think that’s what you’re asking, though.

Even when lifting in the same rep ranges (say 8), why are conventional deadlifts generally heavier? First off, some experts, such as Menno Henselmans, do recommend going quite heavy on the Romanian deadlift, and their reasoning is similar to yours: it’s a shorter range of motion and the sticking point of the conventional deadlift is often removed. The range of motion on your hamstrings is about the same, though, and may even be longer on the Romanian deadlift, depending on how you do it. You also get less assistance from your quads at the start of the lift.

That’s a good question, though, and I think I’m missing pieces of the answer. Let me look into it and add to this in a bit.

Okay, I reached out to Greg Nuckols, MA, and he added one factor: most of us drive our hips further back with Romanian deadlifts than we do with conventional deadlifts. That gives our glutes and hamstrings a longer moment arm to overcome. (And he agreed that not being able to use our quads during Romanian deadlifts is a factor as well.)

Finally, depending on how you deadlift, Romanian deadlifts might be harder because we need to decelerate and then reverse the weight instead of just putting it down on the floor and picking it up from a dead stop. Mind you, if you’re deadlifting with muscle growth in mind, you’ll probably be lowing the barbell down fairly slowly even with conventional deadlifts, so that would be less of a factor.

This response is why I love this site. You took the time to respond, you realized there was something you didn’t know, and you consulted an expert to find the answer and reported back. Awesome stuff!

Thank you, man!

I’ll second this, 100%.

What’s the reason why quads aren’t used in RDL? I suspect it’s because we keep our shins straight throughout the ROM, so there’s zero knee bend.

But going by the same logic, if one does trap bar deadlifts with perpendicular shins, then the quads won’t be used here too. We can extend this to sumo deadlifts as well. Although, I am unable to do conventional deadlifts with a neutral range spine without bending my knee to reach the barbell. So I guess, the quads relatively will be used more here.

You could have straight shins and still work the quads quite hard. You see that with some variations of Smith machine squats.

It’s because you aren’t lifting the weight by extending your knees, yeah. You’re pulling the weight up by opening your hips.

You’ll have some knee bend in a Romanian deadlift. You’ll just keep that knee bend relatively minimal and there won’t be much movement there as you lift through the range of motion.

You can’t extend this to the sumo deadlift because in the sumo deadlift part of your strength comes from opening your legs, extending your knees. That works your quads.

Thanks for the clarification!

Shane,

Do different Towel Deadlift (TD) grip heights have their own benefits and one should do TD at ankle*, mid-shin, knee and mid-thigh heights?

Thank you.

*Assuming hips+thighs anatomy allow ankle-height grip with no back rounding

As a rule of thumb, I’d go with the deepest depth that’s comfortable and that lets you feel strong. The more of a stretch you can put on your muscles (in this case your hips and hamstrings) then the more muscle growth you’ll be able to stimulate, as explained in this article 🙂

[…] compound lifts, we stimulate more muscle growth by stopping just shy of failure. So for squats, deadlifts, barbell rows, and bench presses, there’s less need to go all the way to […]

This was amazing dude, awesome job, learnt a lot from this! I’ll definitely implement a lot of these into my workout.

Thank you, Brenton! Good luck 🙂

In your opinion, does deadlifting help build a stronger squat?

I prefer sumo because of less torque on my lower back. The problem with me is the two lifts don’t seem to coexist. I like to squat once every 5-7 days, and deadlift once a week. Its like the squat limits my ability to go up in sumo and vise versa because I end up with hamstring/adductor strains when deadlifting and quad strains when squatting. If you feel deadlifts don’t make for a stronger squat( which is my thought) I will most likely ditch them. My primary goal is to get strong and better at squatting.

Hey David, that’s a good question, and it can really depend.

For a beginner squatting and help with deadlifting and vice versa, since both muscles involve many similar muscles: quads, hamstrings, spinal erectors, glutes, and so on.

As you gain a bit of lifting experience, though, your hamstrings and spinal erectors become strong enough that the squat stops stimulating much growth in them, becoming more of a quad and glute exercise. Similarly, the deadlift stops challenging the quads enough to stimulate growth there, becoming a pure posterior chain exercise—glutes, hamstrings, spinal erectors, and many of the other muscles in your back. So the two lifts really start to diverge. The exception being the glutes, which are a prime mover in both lifts. Both lifts will bulk up your glutes, and bigger glutes will help with both lifts.

What’s tricky is that a lot of powerlifters will squat and deadlift in a way that’s designed to give maximal carryover. Instead of “sitting down” into a deep squat, stretching their quads fully, and using the quads as the prime movers, they’ll “sit back” into the squat, stop at parallel, and turn it into move of a hip exercise, more similar to a deadlift. This puts more emphasis on the adductors and glutes, both of which can help with the deadlift. So if you’re intentional about it like that, you can keep some carryover between the lifts. And with sumo deadlifts, those work the quads and glutes pretty hard, as well as the adductors and hamstrings, so you might get even more carryover there.

To get better at squatting, yeah, deadlifts probably aren’t the best way to do that. Not that they’re bad, but you’ve got a lot of other options. I’d be looking at other squat variations (high-bar, low-bar, front squats, pause squats), quad-dominant exercises like leg presses, and maybe some good mornings for the glutes. See what’s limiting your squat performance (probably quads) and focus on bulking that up.

Shane, thanks for the feedback. I agree with you.

I like to deadlift, but to me it’s a harder lift to do than squatting. In 1.5 years of sumo deadlifting I just can’t seem to notice any appreciable carryover to the squat, with maybe glute and hip extensor strength.

I have recently been doing box squats which seem to be more helpful in maintaining strength and gains in squats.

Thank you, Sir.

I just started deadlifting again after 25 years off. I’ve been struggling with technique because of injuries and simply having a light build. Your article has helped me immensely, and after about a month of persevering, I’m starting to feel the correct groove of the movement again.

Truly appreciated.

Cheers,

Nick

I’m so glad it helped, Nick. That’s awesome! I hope it continues to go well 🙂

Thank you so much for such a thorough article! Although it seems to target men, I still walked away with some great tips. I fell in love with deadlifting in May of 2019 and was on a roll hitting 165 as my 1RM, then COVID hit which forced me to not lift at all for most of 2020. Now that I’ve built my own deadlift platform at home, I can get back to doing what I love and working on accessory moves to make my lifts better.

– Marianne

My pleasure, Marianne!

This site is loosely aimed at both men and women, depending on the article. And then we have Bony to Bombshell that writes with only women in mind. I’ve got all the illustrations and research done for the women’s deadlift article, but I still need to write it. I hope to get it published soon 🙂

The main difference is that women might prefer variations like the Romanian deadlift, which puts a bit more emphasis on the hips and a bit less on the lower back, and they may benefit more from using lifting straps, so that grip strength isn’t always a limiting factor. But it depends, and we tend to use quite a lot of classic conventional deadlifts in our workout programs for women.

What number of sets x reps do you recommend for the standard barbell deadlift for hypertrophy vs strength. I usually read 3-5 sets of 5 reps. But is this adequate for hypertrophy? Or just strength.

Yeah, 5 reps is okay for hypertrophy, especially on big heavy lifts like the squat and deadlift. Even so, if I’m using those lifts to gain size, then I usually program them in a slightly higher rep range—more like 6–8 reps per set. And with deadlifts, I lower them fairly slowly and I don’t pause between reps. That more fluid rhythm tends to make it a bit easier to lift in those higher rep ranges (as opposed to dropping the barbell, resetting, and then lifting again).

Hi Shane, I have recently been experiencing some back pain/soreness after deadlifting and I think it might be my lower back. The main thing affecting me however is that I suddenly cannot lift what I was normally able and have dropped 40 kilos. When I try and lift I don’t seem to have the strength – almost as if certain muscles aren’t engaging or are blocked. Any advice?

Hey Dave, do you ever take proper deloads, where you drop the volume and intensity of your workouts for a week or so? It’s common to need a break from lifting, especially if you routinely push your limits. Your lower back muscles might simply be asking for a break—a chance to fully recover.

If that sounds like it might be the issue, you could try reducing the load on your lifts by 50% and doing half as many reps for a week. You could do it just for the lifts that work your lower back, but you might benefit from an overall deload.

Hi, Shane

Surely the reason RDLs are programmed lighter is obvious?

With the conventional deadlift you get to put the bar down and rest your grip every rep. With the RDL, you’ve got to hold that bar against gravity for the full set.

If grip or trap strength is your limiting factor, you’re totally right. For me, it’s usually my lower back strength, though, which the conventional deadlift hammers quite a bit harder. (Mind you, I do Romanian deadlifts with about the same weight as I do conventional deadlifts.)

So training the conventional DL for hypertrophy, with 6 reps, how much rest should we have between sets?

Hey guys you are the best. Before reading your websites I was going to the gym 5 times a week trained single muscle groups at the time with no results. 2 weeks ago i have changed completly my routine starting to focus on compounds movement and hell yeah i feel so strong now. I think i have fall in love with the deadlift because I receive an amount of testosterone that i have never experimented before.

I have one questions for you guys, how many times should I deadlift and squatting x week, atm i’m doing just once x week but i would like to increase at 2 days as I gain so much strength from those movements.

This is my current workout:

Day 1:

Barbell row 3×6-8

Lat pulldown 3×8-10

Incline dumbbell bench press 3×8-10

Walking dumbbell lunge 3×8-10

Facepulls 3×12-15

Dumbbell bicep curl 3×10-12

Workout 2: Full Body (push emphasis)

Bench Press 4×4-6

Overhead press 4×6-8

Chest-supported dumbbell row 3×8-10

Leg press 3×10-12

Lying leg curl 3×10-12

Lateral raise 3×10-12

Rope pushdown 3×10-12

Workout 3: Full Body (leg emphasis)

Squat 4×4-6

Romanian deadlift 4×6-8

Bench press 3×8-10

Seated cable row 3×8-10

Seated dumbbell shoulder press 3×8-10

Thanks,

Carlo

my Max is 5 plates after 4 and a half years of training

5 plates is awesome. Nice job, man!