The Bench Press Hypertrophy Guide

The bench press is the best lift for building a powerful chest. It’s also great for bulking up your triceps and the fronts of your shoulders, making it a great overall lift for improving your aesthetics.

The bench press is one of our Big 5 bulking lifts, and in this article, we’re going to go over the best strategies for integrating it into your bulking routine. This article has nothing to do with powerlifting or even powerbuilding, just with using the bench press to becoming bigger, stronger, and better looking.

What is the Bench Press?

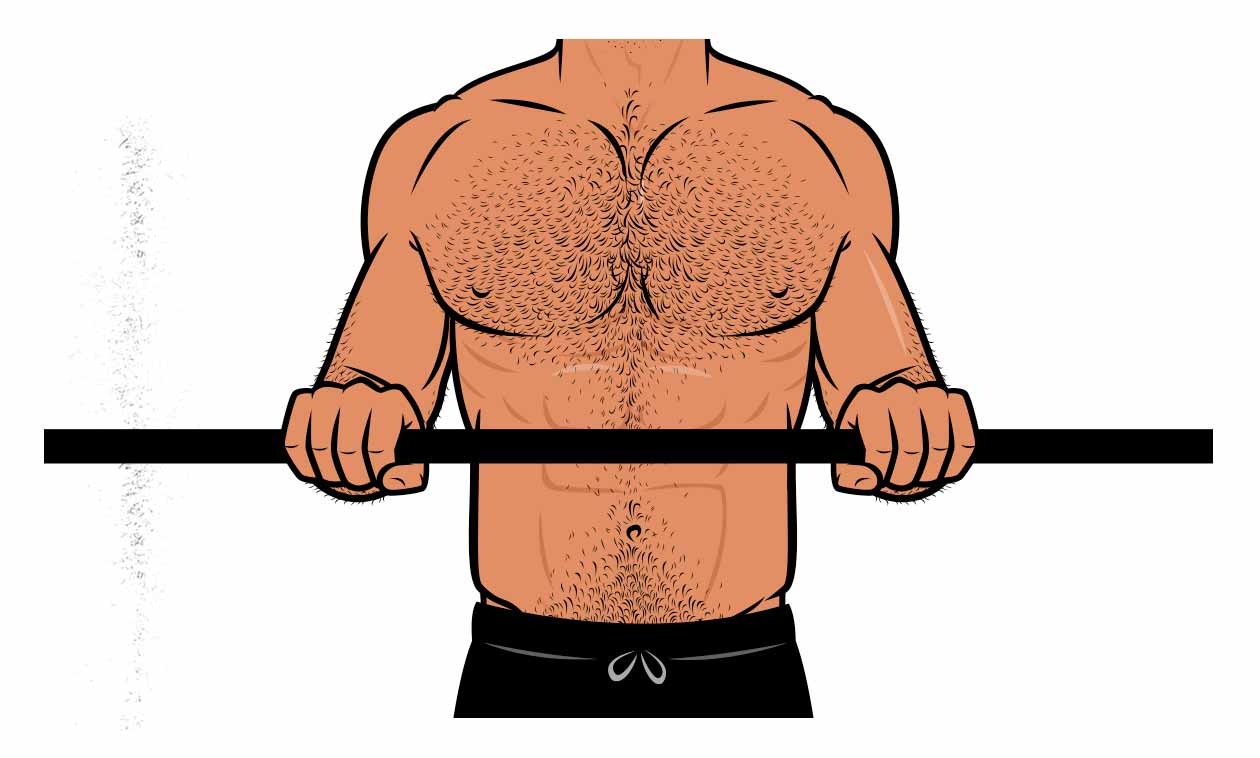

The bench press is a compound weight training lift that’s done by lying on a bench, lowering a weight down to your chest, and then pressing it back up. It can be done with dumbbells, but the barbell bench press engages more overall muscle mass. It’s arguably the best lift for developing your chest, which has made it a popular bodybuilding lift. It’s also a great test of upper-body strength, and is judged alongside the squat and the deadlift in powerlifting competitions.

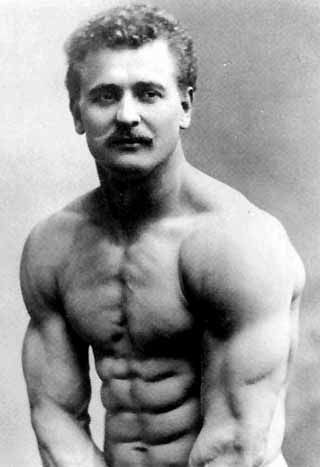

The bench press is relatively new lift. Push-ups have been around for thousands of years, but back when people first started lifting weights, it was the overhead press that was used to develop upper-body strength. If you look at classic bodybuilders, you’ll notice that they have big shoulders and small chests, as with Eugen Sandow:

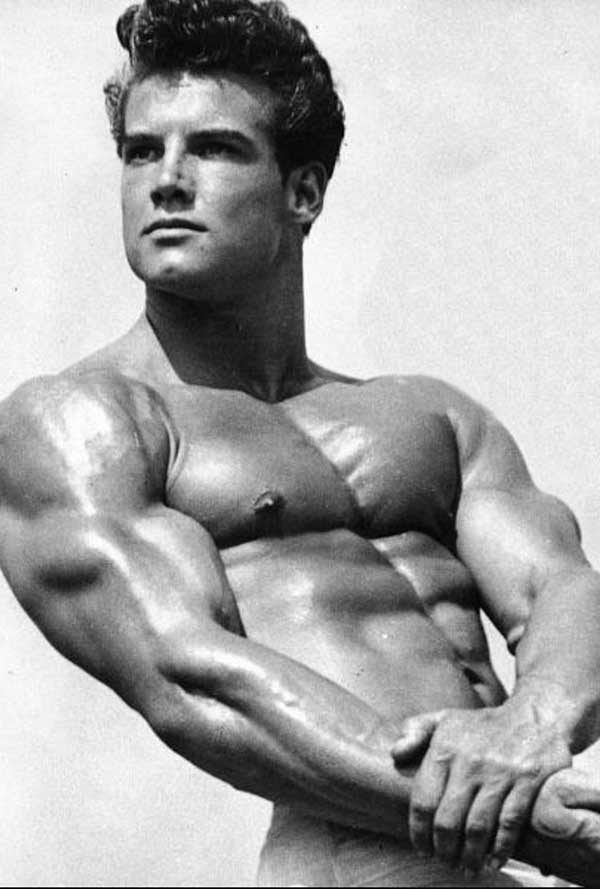

Then, in the 1950s, bodybuilders and actors began to realize that if they did the bench press, they could turn their chests into a dominant muscle group. If you look at the popular bodybuilders in the 50s, you’ll see that they have far bigger chests. Take a look at Steve Reeves:

When people learned that they could build bigger chests simply by adding the bench press into their routines, it quickly became the most popular lift. Now, it’s considered the best lift for improving our appearance by most bodybuilders, and it’s considered the best gauge of upper-body strength by powerlifters, football players, and most casual lifters.

What Muscles Does the Bench Press Work?

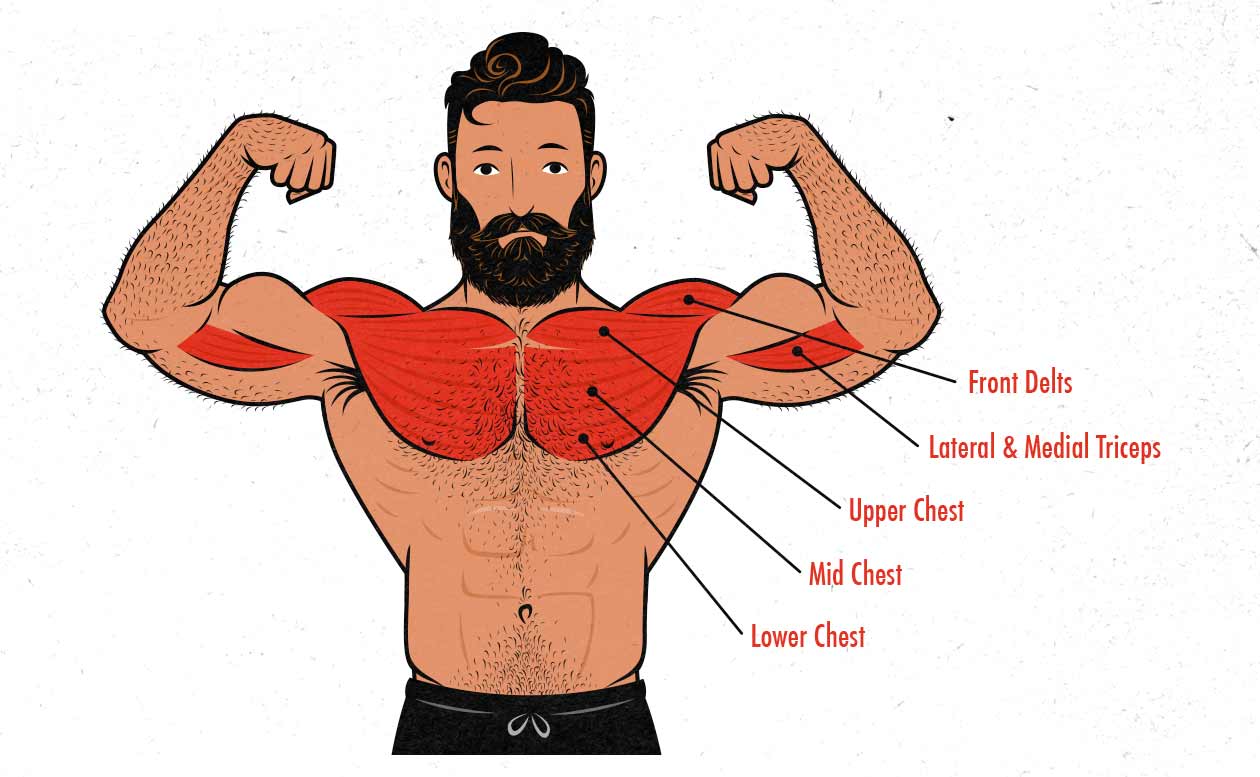

The bench press is a big compound lift that works some of the larger muscles in your upper body: your chest, your shoulders, and your triceps. It doesn’t stimulate as much muscle overall muscle growth as the squat or deadlift, but it’s famous for stimulating the muscles that best improve our upper-body strength and appearance.

For most people, the bench press is the best lift for building a bigger chest. It works your pecs through a large range of motion, putting them under a deep stretch at the bottom of the lift. Perhaps more importantly, your chest is usually the limiting factor, meaning that if you fail to get another rep, your chest has failed. This ensures that your chest is always being challenged enough to provoke muscle growth.

It’s a complete chest exercise, including your lower, mid, and upper chest. If we look at muscle-activation research, we see that the bench press stimulates the upper chest similarly well to the incline bench press. This means that the bench press makes a great main lift for developing your entire chest.

The bench press is also a great lift for your shoulders. The fronts of your shoulders (front delts) assist your chest in pressing the weight up. In fact, when you bench in lower rep ranges, your front delts may even take over, getting slightly more stimulation than your chest. This is why bench pressing for 1–6 reps is often great for your shoulders, whereas benching for 8+ reps tends to demand more of your chest.

There’s even some research showing that the dumbbell and barbell bench press both stimulate the sides of your shoulders (side delts). However, they aren’t the limiting factor, and so they won’t see very much growth.

The bench press works your triceps, but not nearly as hard as your chest and shoulders. We’ll go into more detail below, but as we explain in this article, the bench press is about twice as good for your chest as your triceps.

There are some other muscles that can be worked by the bench press, too. If you drive your head back into the bench, you may find that it helps to bulk up your neck. And if you flex your spinal erectors to create a sturdy arch, you may find that it helps you build a thicker back. But the main muscles that the bench press works are your chest, shoulders, and triceps.

How to Do the Bench Press

There are different ways of bench pressing, and you’ll see some technique variations between bodybuilders and powerlifters, and between people who are trying to emphasize chest versus shoulder growth.

In this tutorial video, we asked the world-record powerlifter, Jordan Syatt, to teach the bench press in a way that’s ideal for gaining muscle size and strength:

You’ll notice a few points:

- Moderate grip width: Jordan recommends using a grip that’s slightly wider than shoulder width. We’ll go into more detail below, but this tends to be ideal for engaging our chests, shoulders, and triceps, allowing us to lift more weight and build more muscle overall.

- Feet on the floor: it’s okay to bench press with your feet up on the bench, but you’ll be able to generate more power if you plant your feet firmly on the floor and use some leg drive (where you use your feet to drive your torso back towards the bar).

- Modest arch: it’s okay to bench with a neutral spine or exaggerated arch, but using a modest, middle-ground arch tends to allow you to bench heavy weights while still getting a deep stretch on your chest at the bottom of the range of motion.

- Retract your shoulder blades: by tucking your shoulder blades down and back, you’ll bring your shoulders into a sturdier, safer position. You’ll also give yourself a deeper stretch on your chest at the bottom of the lift, which is great for building muscle.

Some of these points mean that your overall range of motion is smaller. Using a narrower grip, minimizing your arch, and moving at your shoulder blades would all increase your range of motion. However, you’d be increasing your range of motion at the top of the lift, at the lockout. That part of the lift isn’t very important for gaining muscle size or strength (meta-analysis, study, study). What we want to emphasize is being strong at the bottom of the range of motion, working our chest hard under a deep stretch. That’s what the bench press is best for, and that’s why it’s so good for building muscle.

How to Keep Your Wrists From Bending Back

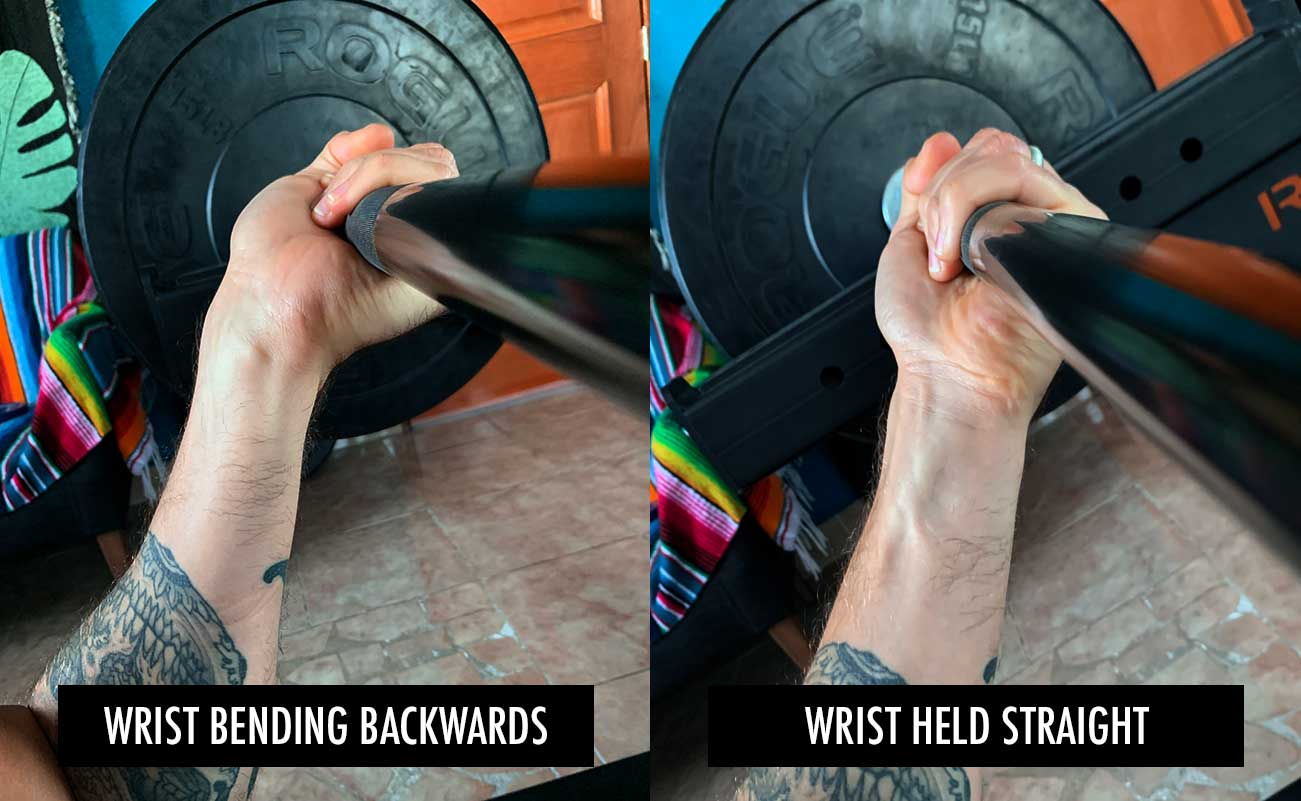

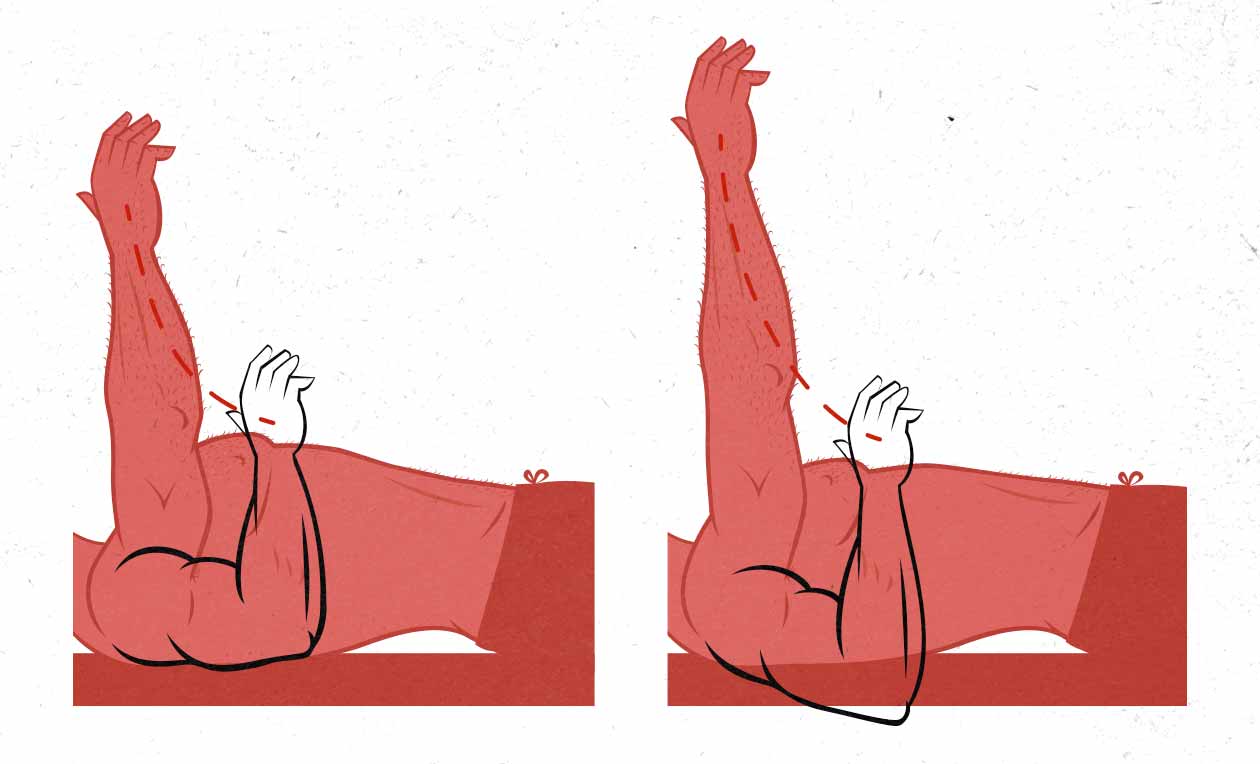

One of the common problems people have with the bench press, especially if they’re newer to lifting weights, is that their wrists bend backwards when they grip the barbell, like so:

When your wrists bend backwards, two problems can emerge:

- You can’t lift as much weight. Your wrist needs to bear more of the weight, your grip isn’t as strong, your leverage isn’t as good, and so it’s harder to use heavier weights. This can limit your muscle and strength gains.

- Your wrists might hurt. When your wrists bend back, it puts a lot of strain on your wrist joints, which can cause pain. That pain often goes away as soon as you start benching with straighter wrists.

So what you want to do is find a way to hold the barbell with a stronger and straighter grip. And the solution is usually pretty simple. First, make sure that you’re gripping the barbell low in your hand, over your wrist joint, like so:

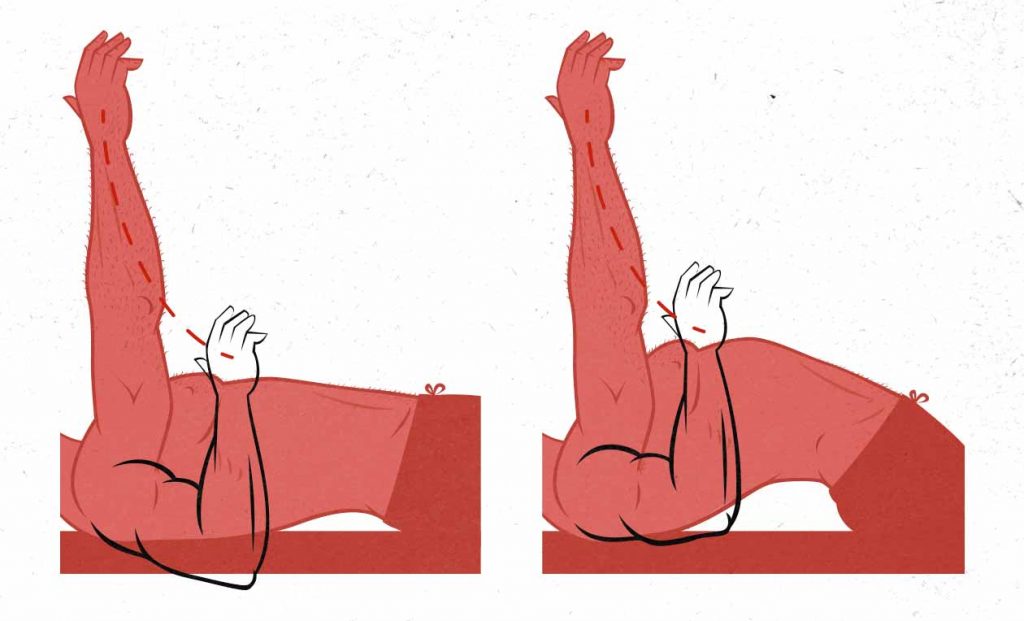

With the barbell held lower in your hand, your leverage will be much better, and you’ll have a much easier time keeping your wrist straight. Plus, even if your wrists bend backwards a little bit, the weight will still be above your wrist joint, minimizing strain.

Once you’re holding the barbell in the correct position, squeeze it as hard as you can. Crush it to smithereens. By engaging your grip and forearm muscles, you’ll naturally hold the barbell in a stronger position, and your wrist will fight to straighten out. Keep squeezing like that throughout your entire set of the bench press. It might feel awkward or tiring at first, but you’ll quickly get used to it, and you won’t ever need to think about it again.

How Can You Increase Chest Activation?

The bench press is famous for being the best lift for building a bigger chest, but that isn’t always the case. Chances are that if one of your lifts is lagging behind, it’s the bench press. And if a muscle group is lagging behind, it’s your chest. This is one of the most common problems that newer lifters run into, and the way that they bench press is almost always the reason.

Sometimes our chests lag behind simply because we don’t bench enough. If we look at Starting Strength and StrongLifts 5×5, they squat twice as often as they bench. They also program the squats ahead of the bench press, meaning that our best energy is going toward the squat, not the bench press. Not surprisingly, that results in much more quad growth than chest growth.

But it’s also notoriously hard for people to fully engage their chests while bench pressing. The chest is the biggest and strongest muscle in the bench press, which means that getting strong at the bench press should be a reliable way to increase our chest size. And it is. You won’t see a small chest on someone who can bench 315 pounds. Unfortunately, as we try to build a bigger bench press, it’s common for our shoulders to be our limiting factor. And if our shoulders are shouldering the load, that prevents our chest from getting a proper growth stimulus, which prevents us from building a big bench press. There are a few things we can do to fix that:

- Bench in a moderate rep range: as we’ll cover below, benching in lower rep ranges can prioritize shoulder and triceps growth over chest growth. If you’re having trouble building a bigger chest, try benching for sets of 8+ reps.

- Bench with a moderate-to-wide grip: as we’ll cover below, benching with a narrower grip shifts the emphasis to the shoulders and upper chest and away from the big muscles in our mid chests.

- Get a deep stretch: try to get a deep stretch on your chest at the bottom of the bench press, which will help to stimulate extra muscle growth.

- Don’t bounce the barbell off the chest: the best part of the bench press for growing the chest is the very bottom, so make sure that you aren’t making that part easier by bouncing the barbell off your chest. If anything, you’ll want to bench with a brief pause on your chest.

- Switch to the dumbbell bench press: the barbell bench press can be an amazing lift for the chest, but if you’ve tried everything and it’s still not working for you, the dumbbell bench press is a good alternative. It combines the pressing motion of the bench press with the squeezing motion of the dumbbell fly, working your chest in both ways at once.

For more, we’ve written an entire article about the best lifts for growing a lagging chest. We even have an entire program dedicated to bringing up stubborn chests:

But the very first place to look is at your bench press technique. And I don’t just mean how good your technique is, I also mean which technique you use. Different styles of the bench press naturally emphasize different muscle groups. Let’s go over the different ways of bench pressing.

How Wide Should You Grip the Barbell?

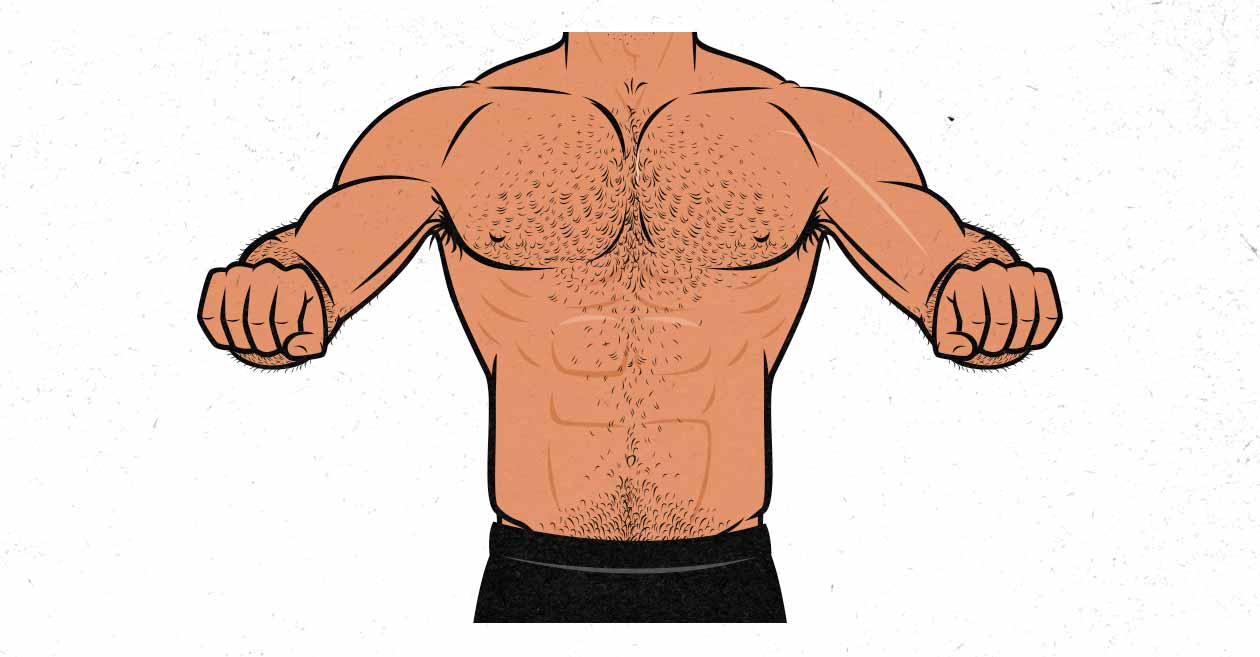

A standard bench press is done with your grip about 1.5x your shoulder width and your elbows flared to about 45 degrees, like so:

This grip width puts your chest, shoulders, and triceps into great positions to press the weight up, and it uses a larger range of motion, allowing for good overall muscle growth. As a result, this is the technique you’ll see in programs like Starting Strength.

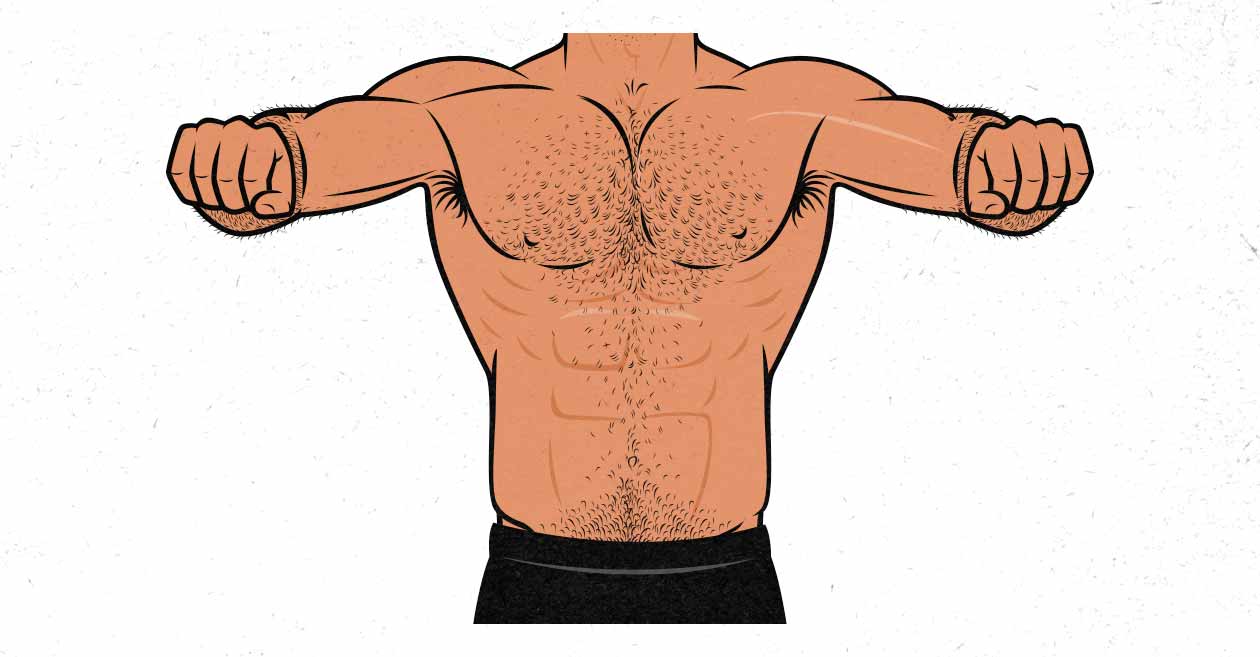

Now let’s compare this against a wide-grip bench press, which is typically done with your index finger on the grip rings (81cm apart) and your elbows flared out as wide as you can safely go (around 80°), like so:

The elbow flare is kept well under 90 degrees, keeping the lift fairly safe for the shoulders. The elbows are also kept underneath the hands, which keeps our triceps at least somewhat involved in the lift.

This is the technique that you’ll see a lot of bodybuilders and powerlifters using. In fact, you’ll see a lot of the thinner powerlifters using an even wider grip, often referred to as an ultra-wide bench press. The rationale is that the wider grip minimizes the range of motion and shifts more of the emphasis to our pecs, allowing powerlifters to lift more weight and bodybuilders to prioritize chest growth. Is that true? Let’s see.

First, let’s look at which muscles are best able to contribute to the lift.

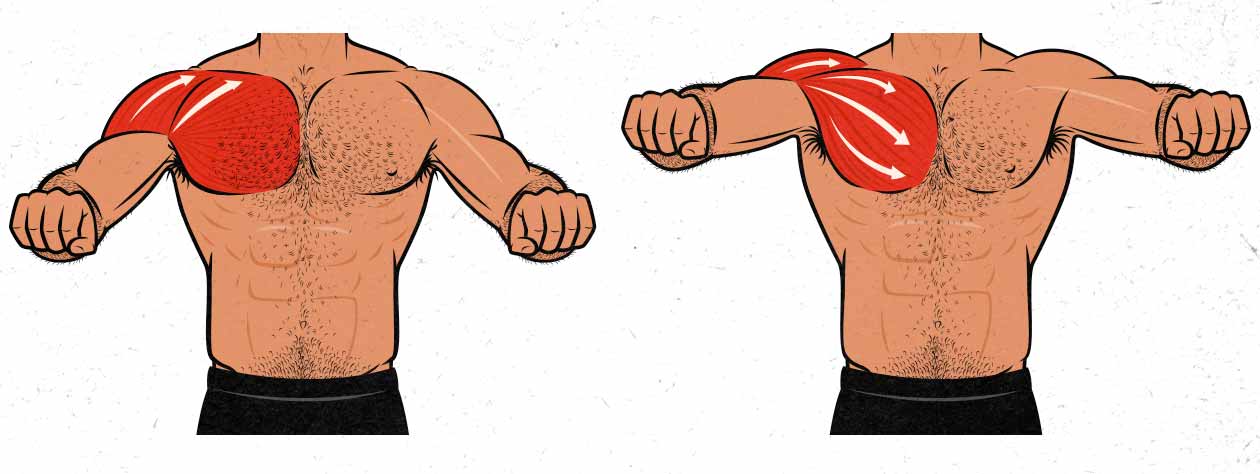

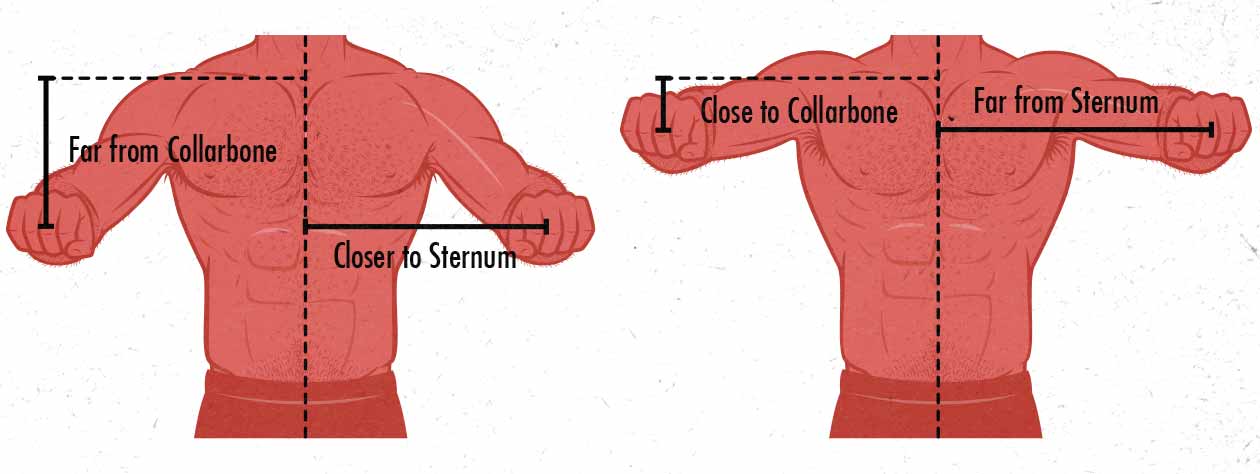

What we’re seeing here is that in the standard bench press, the diagonal muscle fibres of our upper chests and shoulders are in a better position to lift. Then, with the wide-grip bench press, the horizontal muscle fibres in our mid and lower chests are better able to contribute.

The next thing we can do is compare the moment arms. What we see here is that the standard bench press creates longer moment arms between our collarbones and the barbell, making the lift harder on our shoulders and upper chests. Then, with the wide-grip bench press, we see that the moment arms between our sternum and arms are a little bit longer, making the lift a bit harder on our mid and lower chests.

What this means is that with a standard grip width, the lift is quite hard on our shoulders and upper chest, and so we’re more likely to be limited by those muscles, and so they’re more likely to get the bulk of the hypertrophy stimulus. With the wide-grip bench press, on the other hand, we’re more likely to be limited by our mid and lower pec strength, sending more of the growth stimulus to our pecs.

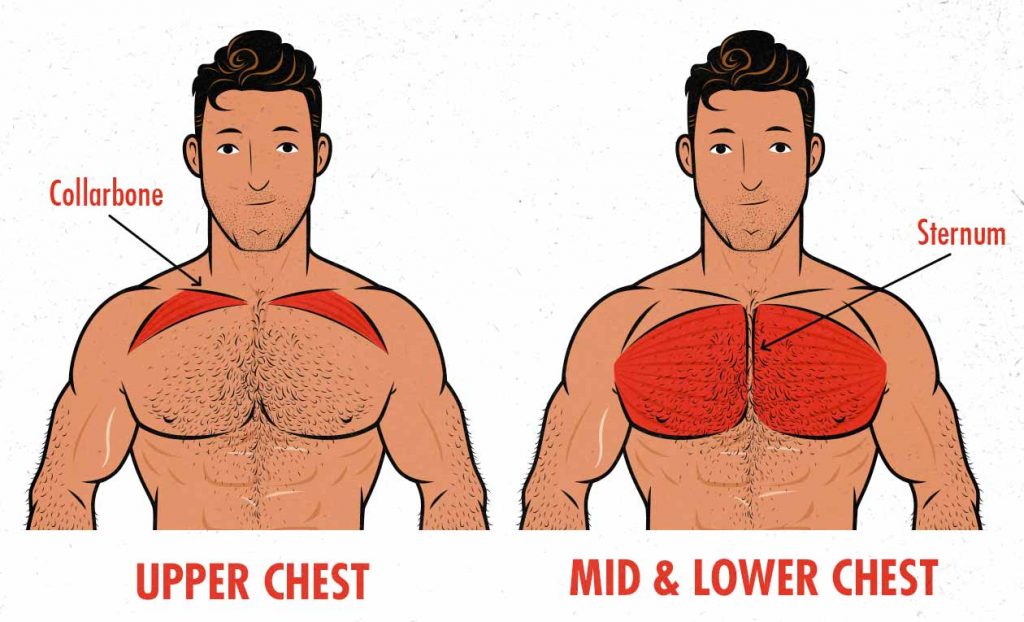

Finally, we need to consider where most of our muscle mass will come from. In this case, it’s the mid and lower parts of our chests that are the beefiest:

We have far more muscle fibres that connect to our sternums (our mid and lower chest) than to our collarbones (upper chest). Our mid and lower chests are far larger and have a far greater potential for growth. When people are struggling to gain mass in their chests, it’s because they’re having trouble activating their mid and lower chests.

Using a wider grip is usually better for our chests. It gives our chest muscles the best leverage, and it also stops our shoulders from being a limiting factor. As a result, most bodybuilders use a wide grip to bulk up their chests, and most powerlifters use a wide grip to bench more weight. Plus, thinner and taller lifters tend to prefer the wide-grip bench press because it shortens the range of motion, cancelling out our lanky arms and thinner ribcages.

On the other hand, using a wider grip will also bring the barbell higher up on your chest, creating a smaller moment arm for your delts, and thus making it a poor variation for bulking up your shoulders. The other downside is that when we flare our elbows, our shoulder blades (scapulae) flare as well. If our elbows are tucked to 30 degrees, we have almost no flare in our shoulder blades. If we flare our elbows to 80 degrees, we have 20–30 degrees of flare in our shoulder blades. The further our shoulder blades flare, the harder they are to tuck, making it harder to get into a sturdy bench press position. As a result, the wide-grip bench press is more of an advanced bench press variation.

If you have a stubborn or lagging chest, and if you don’t have any shoulder pain, then the wide-grip bench press may serve you well. That way you have a true chest exercise in your program. Just be warned that if your chest is lagging behind, you’ll be weaker with a wider grip. After all, it relies on your chest strength. You’ll need to be patient with it. Also keep in mind that if it’s beating up your shoulders, you’re going too wide. Best to choose a grip width that’s easier on your joints.

Now, it’s up to you whether you want to bring up your weaknesses or double down on your strengths. Some guys with strong triceps and shoulders want to double down on that by using a narrower grip. That approach won’t help you build a bigger chest, though.

Similarly, some guys with dominant chests like to use an extremely wide grip in order to lift heavier and eke out even more chest growth. As you can imagine, that’s not great for shoulder or triceps development.

For bulking up, the best approach is to favour a style of the bench press that reduces the disparity between our chest and shoulder stimulation. If your chest is your limiting factor, then consider using a narrower grip and tucking your elbows a bit more. That way you’ll bring your shoulders into the lift. On the other hand, if your chest isn’t even tired at the end of a hard set, then you’ll probably benefit from a wider grip that makes the lift easier on your shoulders. In either case, a more moderate grip is usually best. We can default to somewhere in the middle of the two extremes.

Should You Bench With an Arch?

As a general rule of thumb, lifting with a larger range of motion is better. This is especially true with the bench press. A recent study had the participants doing either full range-of-motion reps or partial reps for ten weeks. At the end of those ten weeks, they tested their strength in all ranges of motion.

Normally, you’d expect lifters to be best at what they’d trained for. You’d expect the group who had been training partials to be best at doing partials. Their muscles would be less versatile, yes, but they’d still be stronger at the specific range of motion they were training in. That wasn’t the case.

The group who was using a full range of motion not only had the most versatile strength, they also had the most specialized strength. They were stronger at doing partial reps than the groups who had been training partial reps.

There may be a simple explanation for this. Using a full range of motion is known to build more muscle. Not surprising, then, that the group who was using a larger range of motion built more muscle mass, and thus gained the most overall strength.

Where this gets interesting is how you define a full range of motion on the bench press. Touching your chest is one definition of a full range of motion, sure, but what about using an arch? The bigger your arch, the smaller the range of motion. Or what about using a wider grip? That, too, would limit the range of motion.

This is where our proportions come into play:

If we look at the lifter on the left, we see that having shorter arms and a barrel chest shortens the range of motion and changes the shoulder angle. That specific point in the lift, with the upper arms parallel to the floor, has the longest moment arms and is the most common sticking point in the bench press. If this stubby dude arches his back, he’ll be shortening the moment arms and increasing how much weight he can lift. Great for powerlifting, not so great for building muscle.

If we look at the lifter on the right, we see that having longer arms and a shallower ribcage lengthens the range of motion and drops the arms down past the sticking point. The sticking point, then, will be when the barbell is a few inches above his chest. That’s not a bad thing. Not only does he have an increased range of motion, but he also has the chance to build a bit of momentum before reaching his sticking point.

However, the details matter. It’s possible that this starting position is so deep that his shoulders are shifting out of a strong position. It’s possible that benching this deep is going to either force this guy to use much lighter weights or, worse, cause shoulder pain.

If you’re a naturally lanky guy (as I am), and benching with a flat back angers your shoulders (as it does for me), then you can fix it by using an arch, like so:

Ideally, we still want a nice stretch on our pecs at the bottom of the bench press. It’s that bottom part of the lift, as our pecs are contracting while stretched out under a heavy load, that stimulates the most chest growth.

But if you’re a lanky guy, you’ll probably get a great stretch on your pecs even with a modest arch. And that arch will keep our shoulders in a better position to press more weight more safely, which more than makes up for any lost range of motion.

How Many Reps Should You Do?

How many reps you do on the bench press depends on what your goals are. If you’re benching to increase your 1-rep max, you’ll probably want to use a lower rep range, whereas if you’re benching to build a bigger chest, you’ll likely want to bench in a moderate rep range.

- 3–5 reps: benching for 3–5 reps is great for improving your 1-rep max but isn’t ideal for stimulating muscle growth. Plus, keep in mind that building bigger muscles will ultimately make you stronger.

- 6–10 reps: benching for 6–10 reps is great for increasing both muscle size and strength, and makes for a good default for most people.

- 11–15 reps: benching for 11–15 reps is great for stimulating muscle growth, but it’s a bit harder to translate it into a 1-rep or even 5-rep max. On the bright side, though, it might be better for emphasizing chest growth, as we’ll cover below.

If pec activation is near-max from the first rep of a set, even with moderate loads, training heavier (say, in the 5-8 rep range) may simply be sacrificing the number of highly stimulating reps you can accomplish for your pecs over the course of a workout.

Greg Nuckols, MA, from Stronger by Science.

To make things more interesting, though, there’s also an EMG study that found that chest activation is maximal right from the first rep of a 10-rep set, and then from there on out, as the pecs fatigue, the triceps and shoulders start to kick in. As Greg Nuckols, MA, speculates, if you’re trying to maximize chest growth, it might help to bench for 9+ reps, which will give your chest a greater number of stimulating reps.

The other implication of this study is that if you’re trying to increase your 1-rep max, the triceps are a big part of that. The lower the rep range, the more important triceps strength becomes. That would explain why so many people swear by skull crushers for improving their bench press strength.

How Often Should You Bench Press?

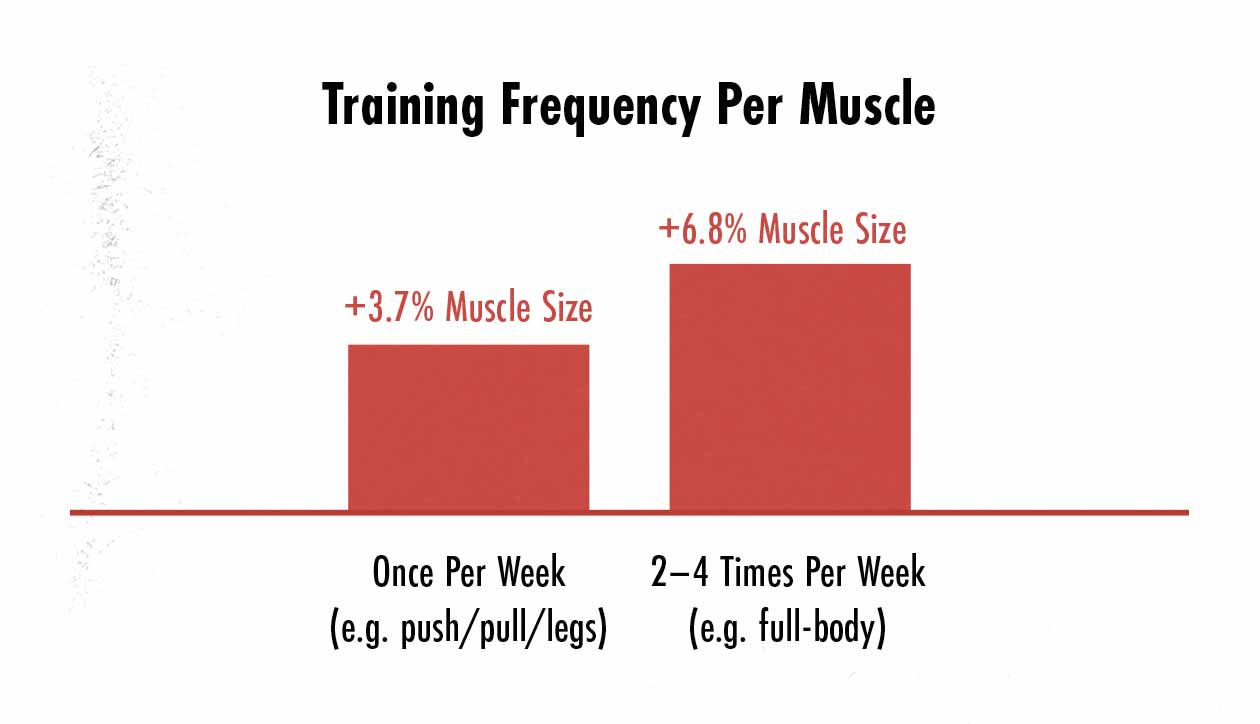

Some bodybuilders prefer to train their muscles just once per week, and some powerlifters prefer to do lighter benching sessions as many as 5 times per week. But most research shows that you can maximize your rate of muscle growth by training your muscles 2–4 times per week (meta-analysis).

Now, that doesn’t mean that you need to do the bench press 2–4 times per week, it just means that you should probably train your chest, shoulders, and triceps 2–4 times per week. Maybe that means doing the bench press and skull crushers on Monday, the overhead press and push-ups on Wednesday, and weighted dips on Friday. That way, you’re training your muscles 3 times per week, but you’re giving your shoulder joints a bit of a break from the bench press, and you’re working your muscles with a greater variety, stimulating more balanced muscle growth.

- Beginners: bench press 2–3 times per week.

- Intermediate lifters: bench press 1–2 times per week.

- Advanced lifters: bench press once per week.

As a loose rule of thumb, if you’re just learning the bench press, you’ll probably want to practice it 2–3 times per week. Then, as you get more experience, you won’t need the extra practice anymore, the stress on your joints will become greater, and the muscle-building advantages of using different lifts becomes more noticeable. That’s when using a greater variety of exercises starts to make more sense.

Bench Press Alternatives

The Push-Up

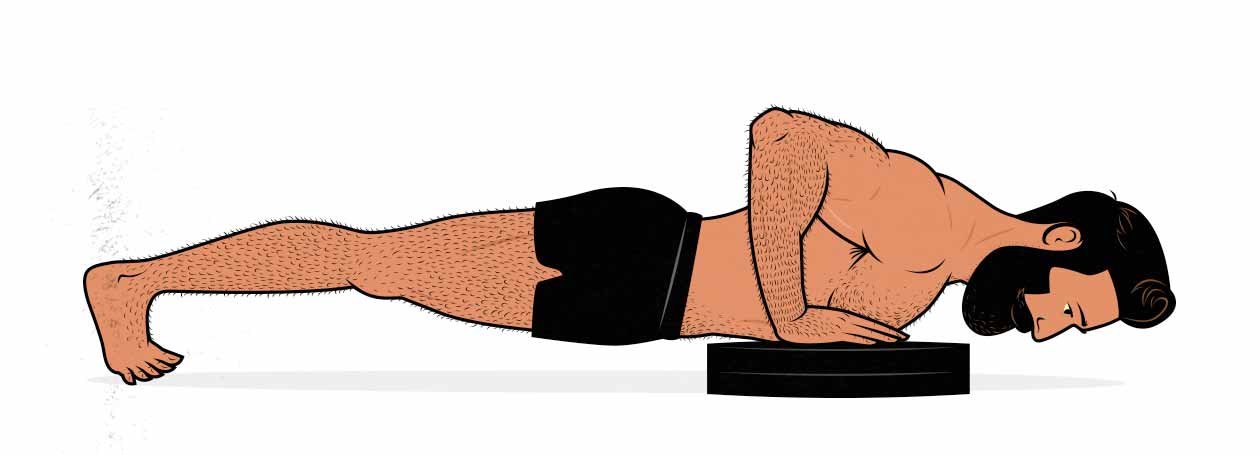

The bench press is a unique lift in the sense that the bodyweight alternative is in some cases quite a bit better than the barbell version. Push-ups are an incredible lift for bulking up our chests, shoulders, triceps, and even serratus muscles. Until we can do a good twenty repetitions, push-ups are even better than the bench press in many ways. And it’s only once we can do more than around forty deficit push-ups that the bench press starts to become the better lift.

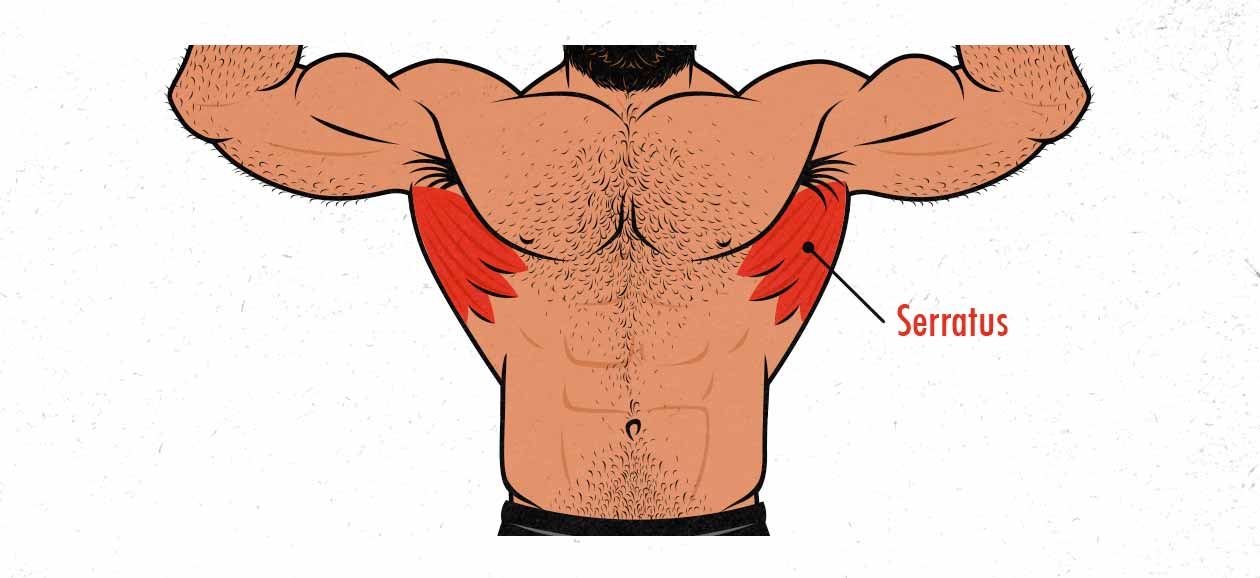

With push-ups, we get all the benefits of the bench press, but we also have our shoulder blades flying free (instead of pinned into the bench). That larger range of motion is better for our chests and shoulders, and it also bulks up our serratus muscles (which are the muscles covering our ribs):

Of course, as we get stronger, regular push-ups stop being challenging enough. Once we’re doing more than forty repetitions per set, our muscular endurance starts to be challenged more than our muscular strength, and they stop being ideal for stimulating muscle growth. At that point, we can elevate our hands with handles or weight plates to increase the range of motion (deficit push-ups). That will stretch out our chests at the bottom of the lift, making it even better for building bigger pecs. But eventually, we’ll grow too strong for that, too.

At that point, we can switch to weighted push-ups. But those won’t last forever either. There are only so many plates you can stack on our backs before push-ups are more like playing Jenga than lifting weights. And even a weighted backpack can only hold so many books.

From there, we can switch to using resistance bands. But, again, eventually, those resistance bands are going to become more trouble than they’re worth. At that point, as any good judge would say, it’s time to approach the bench.

The Dumbbell Bench Press

The dumbbell bench press is the best variation for guys with stubborn chests. While pressing the dumbbells up, your chest will need to fight to keep the dumbbells from falling away to the sides, making it a combination of a bench press and a chest fly.

Overall, it has a few advantages over the barbell bench press:

- It’s the best bench press variation for growing a stubborn chest.

- You don’t need safety bars or a spotter.

- You can lift with a large range of motion.

- It builds fantastic stabilizer muscle strength, allowing near-perfect strength transference to the barbell bench press.

There’s no major downside to the dumbbell bench press, except that it doesn’t tend to be as good for the triceps, and you probably won’t be able to move as much overall weight. Your chest won’t care, though, and the barbell bench press isn’t that great for your triceps anyway. Either way, you’ll still need some accessory lifts to bulk up your triceps.

Another minor disadvantage is that it’s hard to get heavier weights into the starting position, making it harder to lift in lower rep ranges. But so long as you stick to sets of 8+ reps, no problem. (And if your goal is to gain muscle size, you don’t need to dip into lower rep ranges unless you want to. Moderate reps are great for gaining both muscle size and strength.)

How to Increase Your Bench Press

Once you’ve learned how to set up in a strong position and bench press with good technique (as covered above), the best way to increase your bench press is to build more muscle in your chest, shoulders, and triceps (study). Your strength on the bench press is limited by the strength of some of your muscles, so making those muscles bigger and stronger will increase your bench press.

To bulk up the relevant muscles, we can use a three-pronged approach:

- Bench press variations: the simplest way to bulk up the relevant muscles is to do the bench press itself (or close variations). The muscles that limit your performance will be brought closest to failure, and so they’ll get the best growth stimulus. All of the muscle you gain from doing the bench press will directly increase your bench press strength.

- Assistance lifts: the next part of building a bigger bench press is choosing lifts that are similar to the bench press but that emphasize the area that you’re trying to improve. For example, if you want to give your chest some extra emphasis, maybe that means doing a dumbbell or wide-grip bench press. The movement is still very similar to your main bench press variation, but it’s a bit more specialized. Most of the muscle you build this way will improve your bench press.

- Accessory lifts: if you can figure out which muscles are limiting your performance, you can choose lifts that are ideal at making those muscles bigger. For instance, if your triceps are limiting your performance on the bench press, you can choose a lift that’s better at bulking up your triceps than the bench press, such as skull crushers. Not all of the muscle you build will necessarily be relevant to the bench press, but some of it will.

When programming these lifts into your workout routine, keep in mind that it’s usually best so spread them out over the week. That way you’re working your chest, shoulders, and triceps 2–4 times per week, which is ideal for stimulating muscle growth. Something like this:

- Monday: Barbell bench press + skull crushers

- Wednesday: Overhead press + push-ups

- Friday: Dumbbell bench press + pec deck

Using a mix of main variations, assistance lifts, and accessory lifts is the approach that powerlifters take to improve their strength. It’s also the approach that bodybuilders take to build a balanced physique, although they usually call them compound lifts and isolation lifts instead. The difference is that powerlifters use these smaller lifts to strengthen their limiting factors (making them stronger), whereas bodybuilders use them to bring up weak points (building a more balanced physique).

For example, a powerlifter might be chest-dominant when he benches, and so even though his chest is already enormous, if he could build it even bigger, he could increase his bench press. His triceps and shoulders might be proportionally smaller than his chest, but that’s not a concern of his. The bodybuilder, on the other hand, might notice that the bench press isn’t helping him build bigger triceps, and so he adds in skull crushers. It might not improve his bench press, but it does improve his appearance.

So what we want to do is choose a mix of main variations (e.g. standard barbell bench press), assistance lifts (e.g. dumbbell bench press), and accessory lifts (e.g. skull crushers). That way you can build the relevant muscles bigger, allowing you to bench press more weight. What muscles do you want to emphasize? That’s entirely up to you. We’ll go over the pros and cons of each exercise so that you can pick the ones that suit you best.

The Best Assistance Lifts

With our assistance lifts, we’re trying to choose compound lifts that complement our bench press. If you’re trying to increase your bench press, choose lifts that work on the muscles that are limiting your strength. If you want to balance our your muscle growth, choose the lifts that develop the muscles that are lagging behind.

The Close-Grip Bench Press

With a close-grip bench press, the narrower grip shifts emphasis away from your mid chest and onto your upper chest, shoulders, and triceps. It also uses the largest range of motion and keeps tension on your triceps for the greatest amount of time.

Anything that’s significantly narrower than your standard grip can be used as a close-grip bench press. You could simply move your grip in by a couple of inches. But it’s typically done with your grip just slightly outside shoulder width and your elbows tucked in close to your sides, like so:

If you’re trying to build a bigger chest and get stronger at the bench press in moderate or high rep ranges (8–20 reps) then the close-grip bench press probably won’t help very much. It’s not a great chest lift, and when benching for 8+ reps, our chest tends to be our limiting factor. But if you’re trying to increase your 1-rep max, your shoulders and triceps are likely to be a limiting factor, and so the close-grip bench press can be an incredibly powerful assistance lifts.

The Pause Bench Press

Paused bench presses are exactly like regular ones, just with a 1-second pause with the barbell on your chest. In fact, if you have a history of powerlifting, then this is the standard way of doing the lift.

Paused bench presses are used in powerlifting to stop guys from bouncing the barbell off their chests, which is considered cheating. But there are also some potential muscle-building advantages to the pause that you might want to take advantage of. See, the bottom portion of the bench press is when your chest is stretched out under a heavy load, which is great for building muscle. Then, as you press the barbell up, your chest contracts, and your triceps start to contribute more. So by emphasizing the bottom portion, the lift becomes harder on our chests, forcing us to lift lighter weights, but doing a better job of ensuring that we’re limited by our chest strength. It works well as a way to emphasize chest growth.

Dips

Dips are one of the best assistance exercises for the bench press because it trains all the relevant muscles through a large range of motion while allowing your shoulder blades to fly free. This will not only bulk up your prime movers, but it will also strengthen your serratus anterior muscles, which is going to help keep your shoulders healthy as you get stronger.

This makes dips good for a few things:

- Bulking up your pecs, shoulders, and triceps.

- Strengthening your serratus anterior muscles.

- Helping to keep your shoulders healthy and pain-free.

- Improving your shoulder mobility and chest flexibility.

This makes dips surprisingly similar to push-ups, except that dips are much easier to load up heavier (by using a dip belt), making them a great exercise for stronger guys.

The Incline Bench Press

If your upper chest is lagging behind, the incline bench press is a good way to give it a bit of extra love. The incline press is also a great shoulder exercise, though, and the steeper the incline is, the more your shoulders will take over. If your goal is to grow your chest, you’ll want to set the bench up at a 15–30° angle.

The Reverse-Grip Bench Press

If your upper chest is really lagging behind, you may want to consider the reverse-grip bench press. If you use a fairly wide grip, the angles will match the line of pull of your upper-chest muscle fibres.

However, using a reverse grip makes it more likely that you’ll drop the barbell, meaning that you should really only do this lift if you’re safely nestled underneath some sturdy safety bars.

The Feet-Up Bench Press

This is a bench press done with your feet resting on the bench. It removes leg drive, forces you to use lighter loads, minimizes back arch, and seems to be a great overall mass-builder for your chest, shoulders, and triceps.

If your bench press is going smoothly but you just need a bit of extra volume, you can mix these into your workout routine as a slightly lighter assistance lift.

The Floor Press

The floor press is a popular assistance lift for the bench press that works great for stocky guys. However, it doesn’t work nearly as well for guys with longer arms or shallower ribcages given that it limits the range of motion by so much.

Still, if you have sore shoulders from benching, it might be worth a try. Benching from the floor might give your shoulders the stability they’ve been craving.

The Best Accessory Lifts

Of all the big compound lifts, the bench press may be the one that benefits the most from additional accessory lifts. It’s a great lift for bulking up our chests, shoulders, and triceps, but without including some isolation lifts, we’re unlikely to get even growth in those muscles.

The Chest Problem: most guys will get great chest development from the bench press, but depending on your anatomy and lifting technique, it’s possible that your shoulders will bear the brunt of the load instead. The best way to solve that is to adjust your technique to emphasize your chest: use a wider grip or switch to dumbbells. However, that isn’t always a full solution, especially if your chest has been lagging behind awhile now. In that case, choose accessory lifts that emphasize your chest, such as dumbbell flyes, cable flyes, machine flyes, or the pec deck machine.

The Shoulder Problem: some guys are so chest-dominant that their shoulders don’t see much growth from the bench press. In that case, we can switch to a narrower grip with less elbow flare, making the moment arms shorter for our chests and longer for our shoulders. On the other hand, we have the overhead press to take care of your shoulders, so I wouldn’t worry too much about it.

Based on the studies that measured muscle growth in the triceps and the pecs, it seems that the bench press is 78% more effective for the pecs than the triceps!

Menno Henselmans, MSc

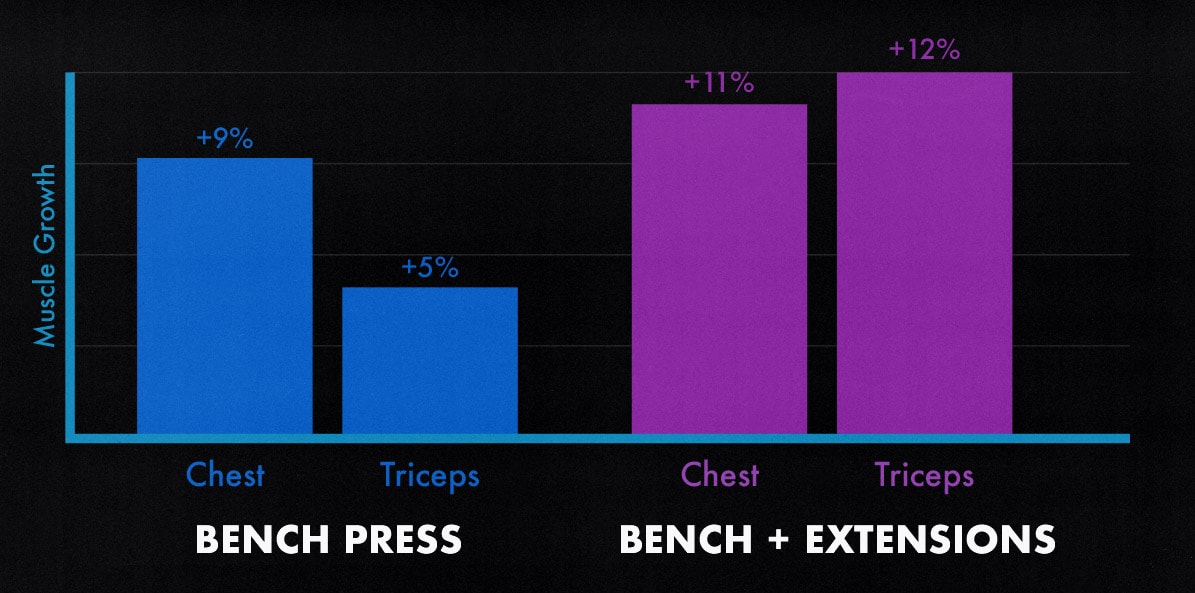

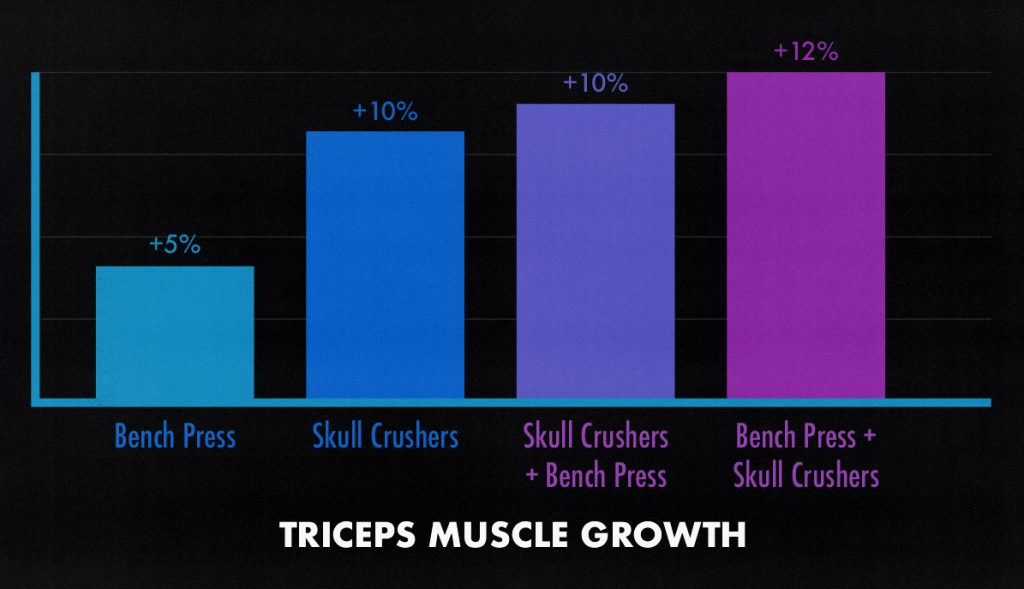

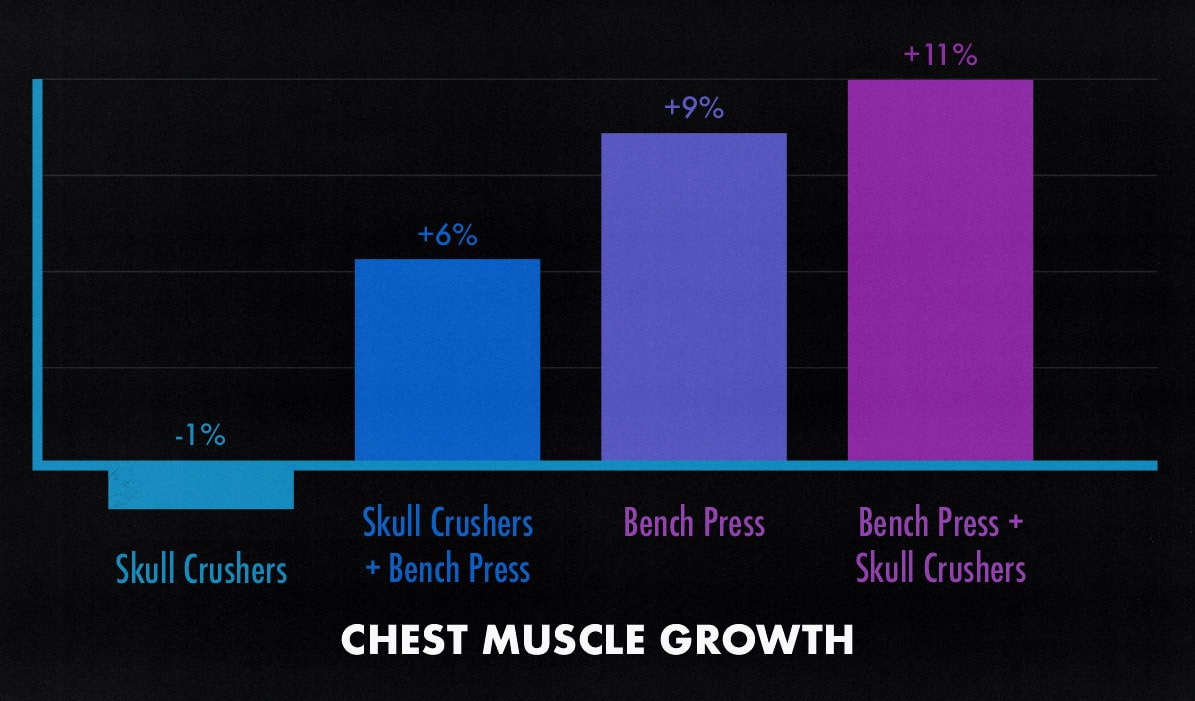

The Triceps Problem: by far the biggest problem with the bench press is the fact that it’s so bad at stimulating growth in our triceps. The good news is that lagging triceps are easy to fix with accessory lifts. If we pop in some skull crushers or triceps pushdowns alongside our bench pressing, the problem vanishes. For an example of that, we can look at the results of a recent study:

We see a small amount of triceps growth from doing the bench press, but we get more than double the amount triceps growth if we add in some triceps extensions, such as skull crushers, pushdowns, triceps kickbacks, or overhead extensions. Even if we forego the bench press altogether, triceps extensions are nearly twice as effective as the bench press for our triceps.

The other neat thing about this study is that it highlights the importance of exercise order. It doesn’t have that much impact on the growth of our triceps (shown above), but if we tire ourselves out with triceps extensions before we do our bench pressing, then our triceps become our limiting factor, and we cut our chest growth in half:

This is all to say that the bench press is an amazing bulking lift, but it really pays to add in some accessory lifts to bring up the muscles that aren’t being fully stimulated by it. And for most people, the best accessory lifts for the bench press are the triceps isolation exercises.

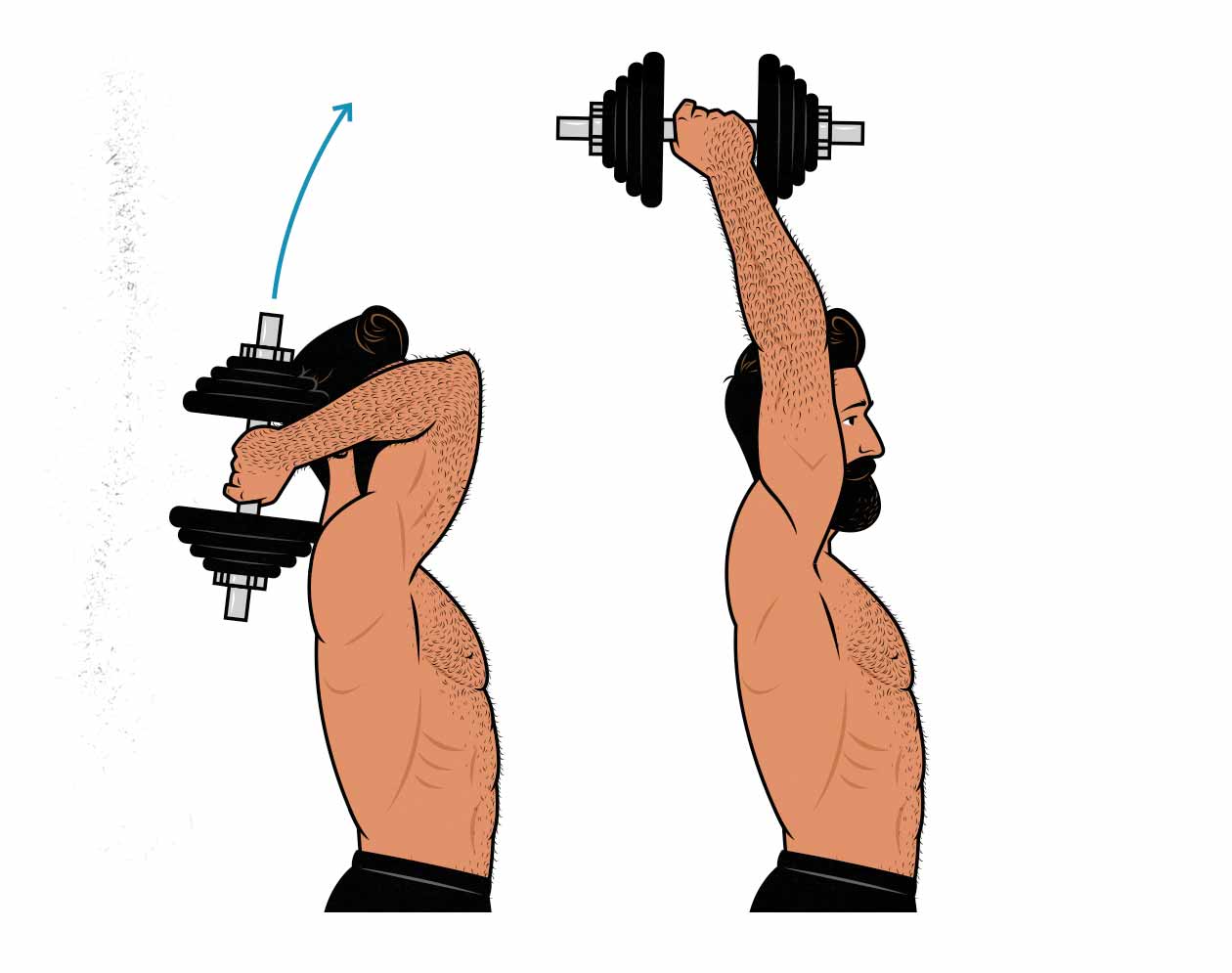

- Skullcrushers (aka lying triceps extensions): these are similar enough to the bench press that the muscle and strength you develop will transfer over quite well, but they put a tremendous amount of emphasis on the short (lateral and medial) heads of your triceps.

- Triceps Pushdowns: These are great for thickening up your triceps, which is important if you’re having trouble locking out your bench press or if you notice that your triceps are lagging behind (which is common if you favour the wide-grip or dumbbell bench press).

- Landmine Presses: These are a great lift for bulking up your shoulders and upper chest while letting your shoulder blades roam wild. This makes them a great accessory for guys who are looking for more shoulder stability and strength. (You’ll need special equipment for these.)

- Dumbbell or Cable Flyes: These are a simple exercise that will help to bulk up your pecs. Get a nice pec stretch at the bottom and a firm pec contraction at the top. That large range of motion will be great for growing your chest.

- Pec Deck Flyes: These are what life is all about. There’s nothing better than a good pec deck machine. They keep constant tension on your chest throughout the entire (huge) range of motion while also providing the stability that you need to load up the machine quite heavy. (I’m seriously tempted to buy one of these for my home gym.)

How Much Should You Be Able to Bench Press?

How much should you be able to bench press? That depends on how big your muscles are, how good at the lift you are, and how good your genetics are. We can’t do anything to change our genetics, so increasing our strength comes down to getting better at the bench press and gaining muscle size.

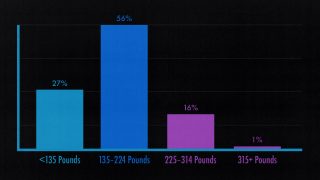

The average man is 5’9 and 197 pounds (CDC), and when he first attempts the bench press, he can lift around 135 pounds (ExRx). However, keep in mind that the heavier you are, the more muscle you’ll tend to have, and the shorter you are, the better your leverage will be.

So, if you’re shorter or heavier, expect to be able to lift more weight. And if you’re taller or lighter, expect to have smaller numbers until you bulk up. When we surveyed our newsletter, which leans taller and thinner than average, it took most guys a year before they could bench 135 pounds.

The other thing to consider is technique. When you first learn the bench press, your muscle size is a factor, but as you get better at it, you’ll improve your coordination and leverage, allowing you to lift more weight without needing to gain additional muscle mass. And so, whether they build muscle or not, most novice lifters can add 40–50 pounds to their bench press with a couple of months of practice.

As we mentioned above, once you’re doing the bench press properly, your strength is largely determined by how big your pecs, front delts, and triceps are. So as you continue gaining muscle mass, your strength will climb ever higher.

If you keep bulking, training to get stronger, and getting better at the bench press, many natural lifters can bench 225 pounds for a casual set of 8–12 reps and/or 315 for a single repetition. Mind you, you’d need to train quite vigorously for it. Most casual lifters never get there.

You don’t need to test your 1-rep max. Singles are an important part of powerlifting, but you can gauge your strength just as well by testing your 5-rep, 8-rep, or 10-rep max. That way, all you need to do is take your working sets to failure and then plug them into a 1-rep max calculator. It’s easier, it won’t distract you from your regular training, and there’s a lower risk of decapitation.

For more on strength standards, we have an article on how much the average man can lift.

Summary

The bench press is a compound lift that will bulk up your chest, shoulders, and triceps. However, you might have trouble getting even development in those three muscle groups. It’s more likely that your triceps will lag behind, but occasionally, it can be your chest or shoulders that refuse to grow.

The first solution is to use a grip width that evens out your limiting factors. If benching works your chest but doesn’t do much for your shoulders or triceps, then try a slightly narrower grip. On the other hand, if benching leaves your chest feeling fresh, try going wider. The trick is to feel it as evenly as possible in all three muscle groups, ideally while still having your chests be the limiting factor.

You can arch your back with the bench press, and keep in mind that the more extreme your arch is, the more it might limit your range of motion, and the more stress it can put on your lower back. The goal isn’t to shorten the range of motion so that you can lift more weight, the goal is merely to keep your shoulder joints feeling strong and safe, and to get a great stretch on your chest at the bottom of the lift. Usually that means benching with a modest arch, but test it out, see how it feels.

The bench press, more than most other lifts, benefits from assistance and accessory lifts. Chest flyes are great for boosting chest growth, the incline bench press is great for improving upper chest and shoulder growth, and skull crushers are essential for bulking up your triceps.

If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. If you liked this article, you’ll love the full program.

I read your article on benching and your chest training recommendations and found it very consistent with my routine for over 25-years. However, due to my age (60 yoa), I only perform the chest routine once per week to include triceps, dips, and close-grip bench. That said, I used to compete in drug-free competitions for years in the 165 lb class (bench only). I refrained from competing in squats because I enjoyed running too. That said, I held the Men’s Rhode Island record with a 385 bench (supportive bench shirt) for over ten years. Now, I do a lot of cross training and running due to my age, but I can still bench (1 rep. Max.) 300 lbs. However, younger guys in the gym are usually shocked when they see me benchpress and often inquire about prior shoulder injuries due to my age. They are surprised when I tell them that I have never had any shoulder injuries or problems. They become more surprised when I tell them that I haven’t done incline bench presses in over thirty years. Many years ago, I saw too many guys in the gym sustain serious and chronic shoulder injuries by overtraining their shoulders with the incline bench and using excessive weight. However, I do a lot of conventional shoulder weight training and pullups. I also read an article written by an individual who held the world record in the 198 Ib class who hadn’t done incline benching in over 5-years. That said, I always tell the young guys that I was able to maintain my health and still able to maintain a rigorous training routine because I was always committed to being drugfree.

That’s amazing, John! A 385-pound bench press at 165 is insanely strong—wow!

That’s interesting about avoiding the incline bench press. I don’t use the incline bench press either. I think the strength curve and range of motion of the flat bench press are better, even for the shoulders and upper chest. With that said, though, I hadn’t heard anything about it increasing injury risk until you told me just now. I’m going to take a closer look at it.

I’m with you on the value of being drug-free, absolutely. We’re natural, too. Although without any bench press records.

Thank you so much for the comment!

Thank you for the compliments. Like I said, I’ll be turning 60 in a couple of months and observed a lot of overly enthusiastic people in the gym who overtrain certain muscles, injure themselves, and stop weight-training altogether. Based on my experience, I just try to provide some common sense training tips and helpful guidance. Due to COVID-19 and my age, my wife does not want to go back to the gym, so I’ve begun rebuilding a garage gym with only the essentials. I sold or donated my equipment several years ago because gyms became so inexpensive. This morning, at 5 AM, I completed a routine consisting of several sets of sit-ups (30 per set), along with stretching, and a 180 pull-ups/180 pushups routine that is completed within 32 minutes. I then ran 3.5 miles in the neighborhood to complete the workout; I was done for the day. I try to run 3-4 times per week to maintain my cardio training. If possible, I do highly recommend pull-ups and chin-ups routines. It supplements many other exercises and strengthens your core. I’ve been under 170 lbs for 35 years and still feel healthy and motivated. Just remember, when to speak with someone who has sustained chronic shoulder injuries (rotator cuff), ask them if they performed a lot of heavy incline benching sets throughout the years. Good luck and stay positive.

I’ll be 57 in January 2020.

I’ve benched pressed for many years, probably 30.

I also use to play baseball, so I’ve been very careful not to be over zealous with benching, but have liked the results and advantages it has given me over the years (I still play baseball), so when I have gone to the gym I have ONLY benched pressed.

I’ve had people admonish me for JUST bench pressing, but one, we are all different, and two, we all have different goals. In my case I wanted to look good (in a shirt/without shirt) and I wanted to be strong enough on a baseball field, and for those 30 years I’ve accomplished that, which, with increasing age has set me apart from guys that stopped working out/working on themselves years ago.

I’m 5’7″, 195pds which according to BMI makes me “fat” but I am nothing of the sort. Besides the bench, and playing baseball I do run (jog).

Because of COVID gyms shut down in March 2020. I was fortunate to find a “private gym” and for the first time in my life I used the Smith bench, with the spotters and hooks on the side. I didn’t like the idea, but I wanted to continue bench pressing and because of COVID, closed gyms I had to be happy with what I could get and Smith allowed me to maintain my “gains” and stay how I was accustomed. Using the Smith machine took time for me to get used to – in part because I never used one and two simply to find a comfortable, consistent way of using it, which eventually I did.

I used the Smith from late March until early October and with gym opening up I am back to the normal bench press, but as you can imagine, it was an adjustment going back to the “normal” bench press because we lift the bar and simply have complete control of it, unlike the Smith that bails you out if needed.

It hasn’t been easy but this morning I lifted and it went fine, though I lifted my 225 seven times, one, rest, two, rest, three, rest etc.

That is how I have always lifted – just one time and then rest. Usually I lift until I have done 18-20 times. This morning was 7.

I’m a night person so lifting in the morning is not my preference, but because gyms get crowded later I have chosen to lift when the gym opens, when I am basically alone, not rushed by anyone, but I know I am not as “awake” or stoked as I am when I lift later in the day – but tradeoffs (safer vs. half-asleep).

Personally I believe the transition from Smith back to conventional bench pressing has F with my shoulders (body), so I am taking it slow and listening to my body, which is why this morning I just did 7. Last week, if I remember I did about 10-13 on Wednesday, but I lifted in early evening and because there were more people I didn’t feel I had the luxury to “take my time”, so between being more awake and not taking as much time between reps I did 10-13. So in general I am ok with progress since going back to normal bench pressing.

I’ve never done drugs, steroids anything other than putting in the work.

I think I may have developed some “tennis elbow” but don’t know and with virtual doctor visits what is value there, so for now my hardest lift is the first one – after that the other ones are pain free.

Maybe you’ll admonish me but I CAN’T, or don’t want to “warm up” with less than 225, so I start with 225 and crank out my reps at 225. I don’t warm up with anything less. I never, ever have in my 30 years of lifting.

My logic (mental) is I am strongest when I start so I might as well start with the weight I want to lift. Pyschologically it is easier for me to start at MY WEIGHT than start low and go up.

I’ve also always used a closer grip – I know that helps the chest cavity, uses more triceps and again because I have gotten the results I’ve wanted, between only doing the bench press, closer grip and starting at 225, I’ve done the same thing for all these years.

Prior to COVID (before March 2020) I benched pressed, regularly, about 265 or so but because of going to Smith, and now back I haven’t wanted to push myself to go that high so I’m at 225 – in years past I’ve chosen to maintain a good bench weight instead of discovering how high I could go – why? because I play baseball and keeping my throwing arm in good shape was also important.

So in between bench pressing, I also throw a baseball to ensure my throwing arm also gets in the work it needs so bench pressing doesn’t ruin my throwing arm.

Lastly with this possible tennis elbow I’ve refrained from taking Aleve. Fortunately I am in very good health and have never been on meds. and I simply see no reason to put an Aleve or two just to bench press, even if it may help with the tennis elbow.

For now, with the first lift I am “pushing” through it to get to the other ones which are much easier.

Sorry for lengthy post but I wanted to give you an idea about what I’ve done and I welcome your feedback, constructive criticism over how I’ve done things, what I may have been doing wrong all these years, like maybe not warming up.

Go at it and tell me your thoughts on the picture I’ve painted about me.

PS: I live in Florida

Hello Shane,

Bit of insight please. I began benching in February this yes at around 45kg. I built up to reach 62kg comfortably (3 sets of 8 reps). I took a 3 week break and recently started again this week. I went straight to 62kg on the bench but I’m seriously struggling to even get to 5 reps. I’m not sure should I drop the weight?

Hey Tatenda, nice job adding those 17 kilos to your bench press! That’s awesome.

It’s normal for your strength to suffer when you take a break from lifting. It’s not necessarily due to muscle loss. Oftentimes it’s just that you’ve gotten a bit rusty. I wouldn’t worry about it too much. I think you’ll regain those three reps within a week or two. You just need to get back into the groove of it.

In the meantime, yeah, you can drop the weight so that you can safely get 6–8 reps. Build the weight/reps back up from there.

Why are chest dips considered an accessory exercise rather than one of the Big 5? Your article already observes that dips train important stabilizer muscles in addition to all the muscles which the bench press trains. Weighted dips can be programmed with progressive overload exactly the same as the bench press. Dips can be trained at least 20% heavier than the bench press (when we include body weight), according to Strength Level. They are frequently used by powerlifters as an alternative to the bench press, according to Starting Strength 3rd Ed. (p. 273).

The bench press allows the lifter to lower weights which are far in excess of what the shoulder muscles, ligaments, and joints are able to bear without injury, which is exactly what they do at the lower ROM of the bench press. The National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM) has cautioned against heavy benching below parallel for this reason (see “Elbow Position and the Bench Press”). The U.S. Army Public Health Center cautions against heavy benching for the same reason in its Fact Sheet 12-023-1119 and suggests dips as an alternative. The Bench press is by far the most dangerous exercise of the Big 5 with shoulder injuries being the most common type of injury caused by the exercise.

Dips aren’t possible for beginners, but beginners can get the same benefits from push-ups. The dip is, after all, essentially an advanced push-up variation. Dips are known for being hard on the shoulder joint, but they also train important shoulder stabilizer muscles, unlike the bench press. Chest dips further mitigate the problem by improving the angle of the arm, an angle essentially the same as a decline bench press but less dangerous. Shoulder injury is mainly becomes a concern only after the humerus drops below parallel with the floor, something which isn’t necessary for the exercise to be effective.

Hey David, you’re not wrong. We’ve chosen 5 big compound exercises that work all of the major muscle groups in your body. There are lots of great compound exercises that we don’t list here, including push-ups, rows, loaded carries, and dips.

You can also swap out some of these lifts with others. You could swap out the bench press with push-ups or dips. You could swap out chin-ups with pull-ups with rows. You could swap out conventional deadlifts with trap-bar deadlifts. You’ve got a ton of options. We’re just giving a default set of exercises. In our programs, we usually let people pick between the bench press, dips, and push-ups. It’s a dropdown menu. You pick your favourite.

We default to the bench press because, on average, people have an easier time building their chests with the bench press than with push-ups or dips. Most people find that the bench press feels more stable and allows them to work their chests harder. For example, when I do dips, they feel a bit less stable, especially in lower rep ranges. I also tend to get more pump and soreness in my triceps than in my chest. That’s not true of everyone, though. Some people do much better with dips than the bench press.

I wouldn’t worry too much about how much weight the exercise allows you to lift. Front squats and high-bar squats are better for building muscle than low-bar back squats despite them being quite a bit lighter.

If benching is hurting your shoulders, yes, I’d adjust your technique, use a different rep range, or switch to another exercise, such as push-ups or dips. But most people are able to bench without any issue, provided they do it in a sensible way. If your goal way to lift in the safest possible, way though, I think the winner would be push-ups. I’m not sure dips have a lower rate of injury than the bench press. I’m not sure about that. I’d need to check. But again, these are things where people can simply listen to their bodies. If a lift makes their shoulders hurt, they can adjust the lift or switch to a different one.

I’m not sure what you mean about the bench press not training shoulder stabilization. We need to stabilize our shoulder joints when doing the bench press.

Our joints don’t care about what angle they have in relation to the floor, but what angle they have in relation to one another. The elbow moves further behind the body during dips than the bench press. If that were a dangerous position, dips would be worse. But that’s not necessarily a dangerous position. And also keep in mind that when we’re talking about lifts being “dangerous,” we’re talking about very small risks of injury. Lifting is safer than most recreational sports, safer than jogging, and arguably safer than not lifting. There aren’t many activities that are safer than lifting weights.

I do banded deficit push-ups and have made lots of gains. I could easily carry 140 pounds of resistance for a set of 8. But I recently benched for the first time and I could only bench 145 pounds. Is there a possible reason for this?

Hey Abdulallah. Yeah, I have a guess for what’s going on. Banded push-ups make the lift harder at the lockout. The bench press is hardest at the bottom of the lift, where your chest is under a deep stretch. You aren’t building strength in that deep part of the range of motion with banded push-ups.

You could try putting weights on your back or wearing a weight vest when doing deficit push-ups. That’ll build muscle better than bands. Or just stick with the bench press. The bench press is great.

Since I don’t have any access to weights, how could I make resistance bands more effective for strength?

It seems to correlate well with curls and isolation exercises but not exactly for compound exercises?

We’ve got an article on the effectiveness of resistance bands for gaining muscle. Long story short, they probably aren’t quite ideal for gaining muscle. We stimulate more muscle growth when we challenge our muscles in a deep range of motion. Bands do the opposite of that. They make exercises more difficult at shorter muscle lengths. That’s not the end of the world, but it explains why it can be harder to build muscle with resistance bands.

For compound lifts, I’d incorporate more bodyweight exercises. Bodyweight exercises are very good for building muscle if you can handle the pain. (And if you can handle the pain of resistance bands, you should be able to handle the pain of bodyweight exercises.) We have an article on bodyweight hypertrophy training here. That should give you everything you need.

If you ever want to make your training feel easier or less painful, you could get some adjustable dumbbells. You don’t have to, but that’s why so many people love weights so much. It makes training much less painful, much more enjoyable. (Except for the subset of people who enjoy the pain of higher-rep sets.)

Great article overall, but wish you would have touched on ideal tempo and rest periods for hypertrophy.

I can do better than that! We have a full article on lifting tempo for hypertrophy and another on rest periods for hypertrophy.

Hey Shane, wanted to ask you about shoulder safety.

I recently strained my Rotator Cuff from (I believe) a too-large Range of Motion on the Dumbbell Bench. It could also have been from Dumbbell Flyes.

I know the importance of the stretch, but do you have any recommendations for keeping shoulders healthy? Keeping the barbell above the chest while benching?Neutral Grip Dumbbell Bench? Keeping ROM limited on Dumbbell Flyes?

Thanks for your work on these websites man, they’ve truly changed my life.

Hey David, thank you so much!

That’s a good question, and it’s slightly outside of my area of expertise. I’m pretty good at giving general best practices. I’m less good at helping people rehab specific issues. That’s more up Marco’s alley, and it’s something he helps people with in our coaching community.

For most people, doing bench presses and flyes with a large range of motion is great for their shoulders, provided they’re using good technique and lifting in a way that feels good on their joints. There are exceptions to every rule, though. Some people might benefit from adjusting that range of motion to suit them better. It might also be that something like a dumbbell fly doesn’t suit your body very well.

Trying a neutral grip sounds like a good idea. You could also try a narrower grip. Or maybe you don’t flare your elbows as wide. Maybe you need a bit more of an arch in your lower back. Or maybe you should swap out the bench press for push-ups for a little while (to build up more serratus strength) and add in some face pulls (to strengthen your rotator cuff and upper back). If you do push-ups, remember not to flare your elbows all the way out. Keep them in tighter, as if you were going to push someone.

I hope that helps, and I hope you recover well!