How Range of Motion Affects Muscle Growth

There are three conflicting ideas about how the range of motion we use while lifting weights affects our muscle growth:

- The first idea is that lifting with a larger range of motion means doing more work, which will then stimulate more muscle growth.

- The second idea is that keeping constant tension on our muscles throughout the set gives a better muscle pump and thus stimulates more muscle growth.

- The third idea is that doing heavy partials can strengthen our tendons and bones, allowing us to build more muscle in the longer term.

All three of these ideas seem to be true. For maximal muscle growth, we probably want to use a smart mix of at least the first two, and perhaps even the third.

What is Range of Motion?

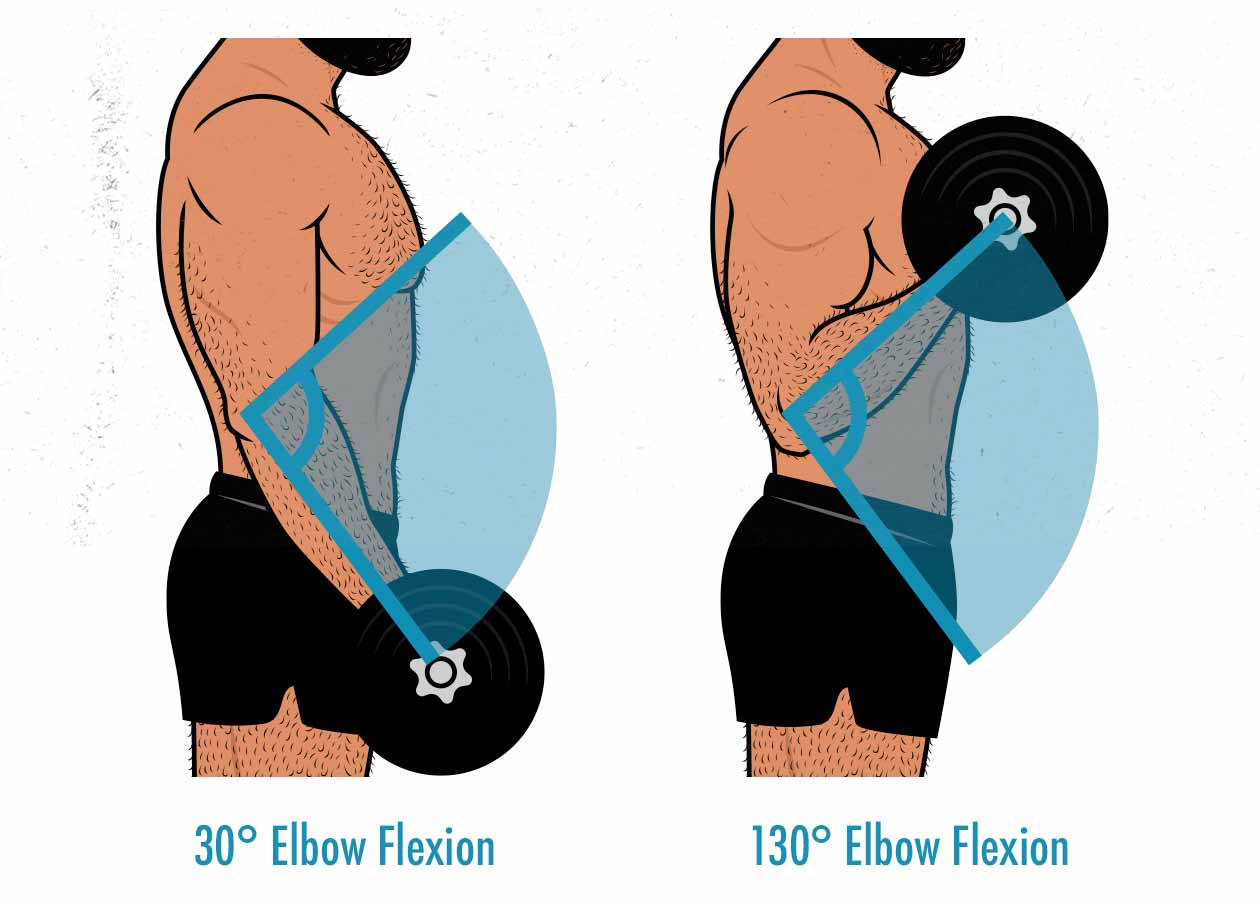

When we’re talking about “range of motion” while lifting weights, what we mean is the movement around a joint. So if we take a simple lift like a biceps curl, we get something like this:

So what we’d say here is that we have 100° of range of motion at the elbow joint, which is pretty sweet. The biceps are starting slightly stretched and finishing fully contracted. This qualifies as a large range of motion.

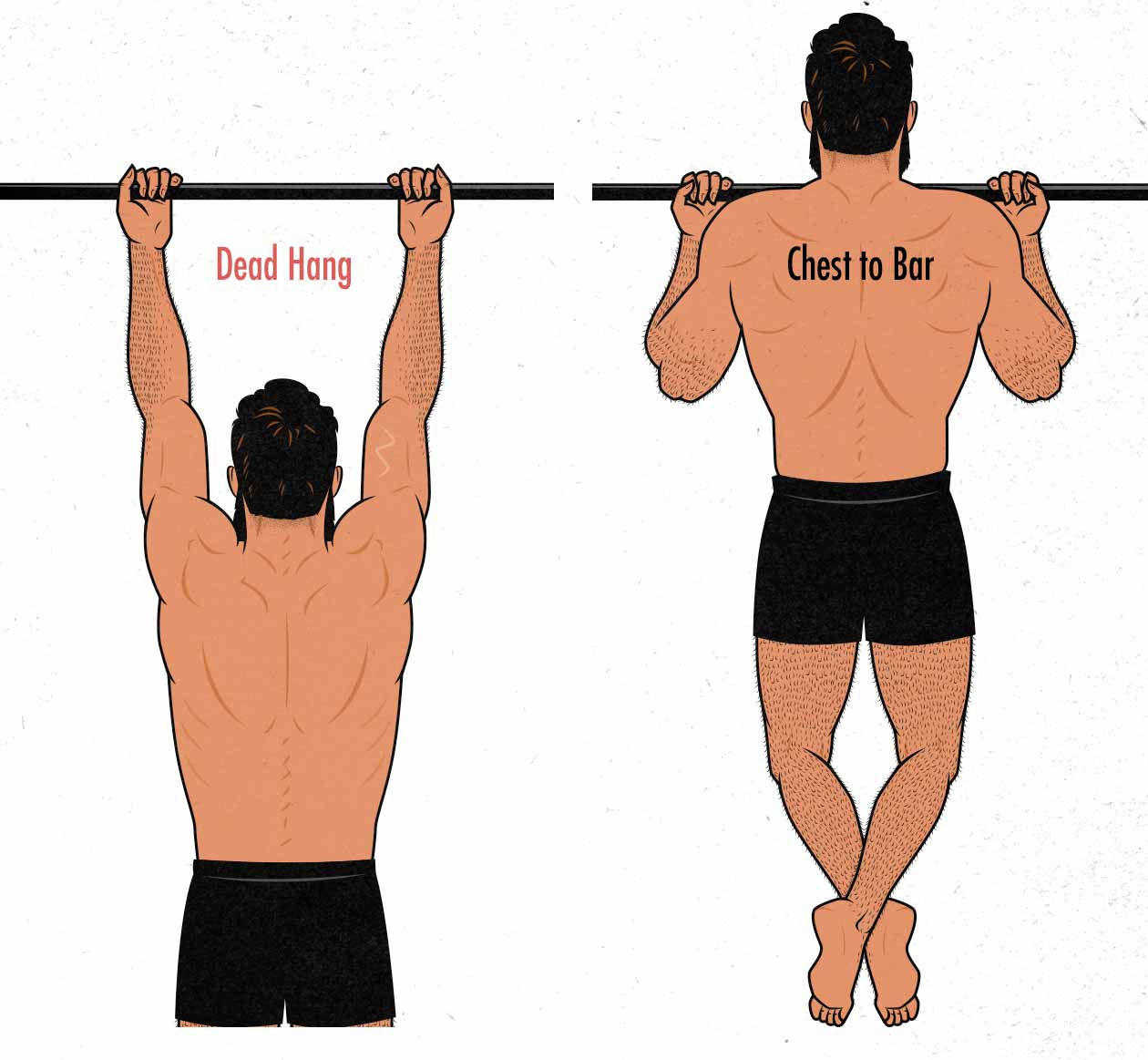

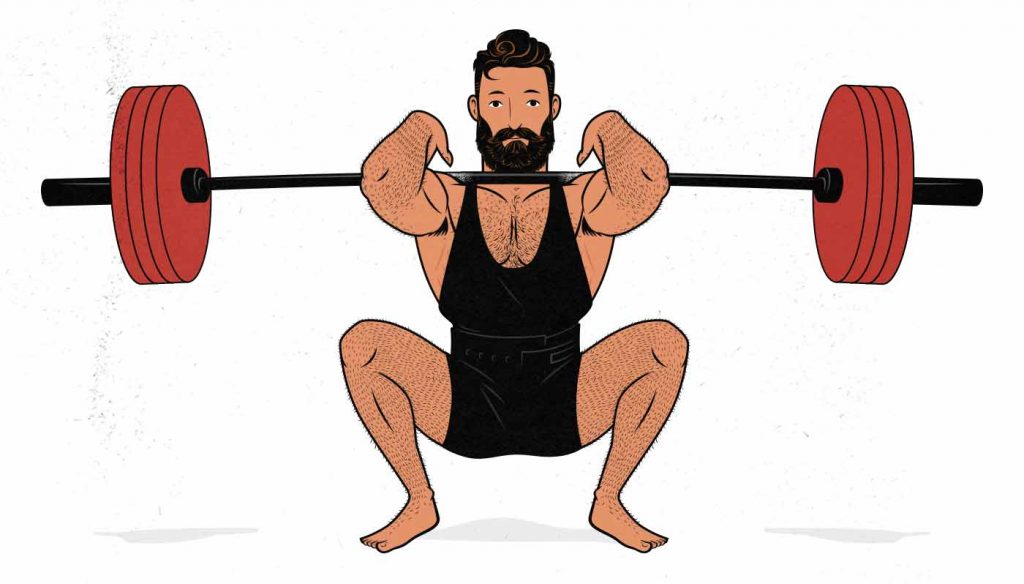

Now, if we take a bigger lift, like the chin-up, then we can blow that range of motion out of the water:

What we’re seeing here is the same 100° range of motion in the elbow joint, but now we’re also extending the shoulder joint through a 180° range of motion, which is a full range of motion for our lats. Again, this is an example of a large “full” range of motion.

Some Parts of the Range of Motion Matter Much More

The Sticking Point Is What Challenges Our Muscles

Lifting with a large range of motion is a good rule of thumb, but it’s not quite that simple. Different parts of the range of motion stimulate different amounts of muscle growth, making some parts much more important than others.

First of all, our muscles only grow when they’re challenged, and some parts of the range of motion are more challenging than others. If a lift is equally challenging throughout the entire range of motion, we say that it has a flat strength curve. But most lifts are disproportionately challenging at one specific part of the lift. We call this the sticking point of the lift.

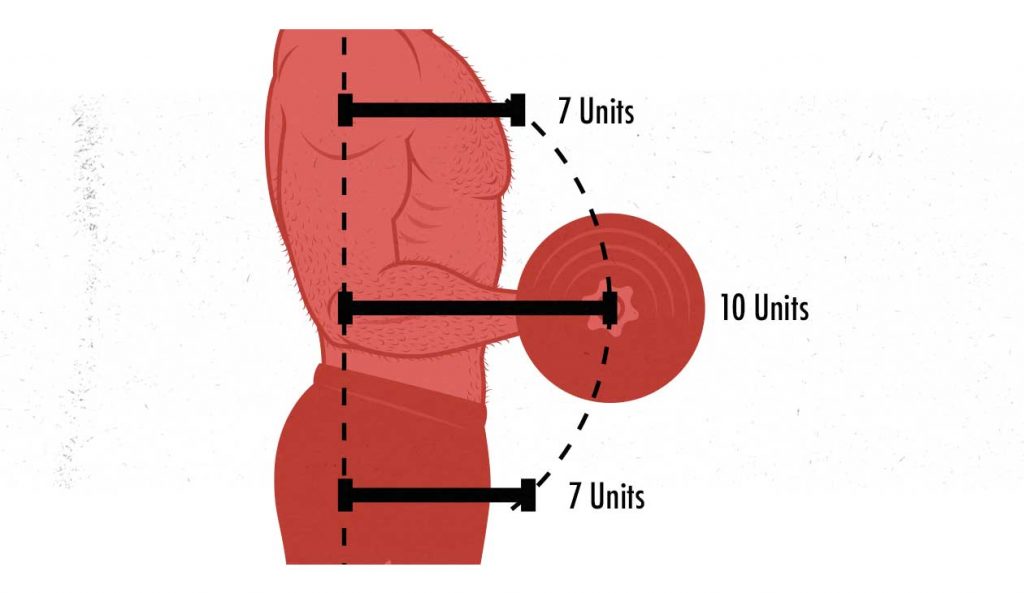

In general, lifts are hardest at the point where the external moment arms are longest. Squats are hardest when our thighs are horizontal, the bench press is hardest when our upper arms are horizontal, and biceps curls are hardest when our forearms are horizontal. Our muscles grow when they’re challenged, this is the part of the range of motion that challenges our muscles the most, and so this part of the range of motion stimulates a disproportionate amount of muscle growth.

Challenging Stretched Muscles Boosts Growth

The main mechanism of muscle growth is something called mechanical tension. The more mechanical tension we put on our muscles per rep, per set, and per workout, the more muscle growth we can stimulate (up to a point). Where this gets tricky is that different parts of the range of motion put different amounts of mechanical tension on our muscles.

Our muscles are sort of like elastics. When we stretch them past their natural resting lengths, they want to spring back. This adds “passive” tension, increasing the overall mechanical tension on our muscles. This means that, for example, when we stretch our chests out at the bottom of a bench press, or our quads at the bottom of a squat, or our hamstrings at the bottom of a deadlift, we stimulate extra muscle growth with that extra mechanical tension.

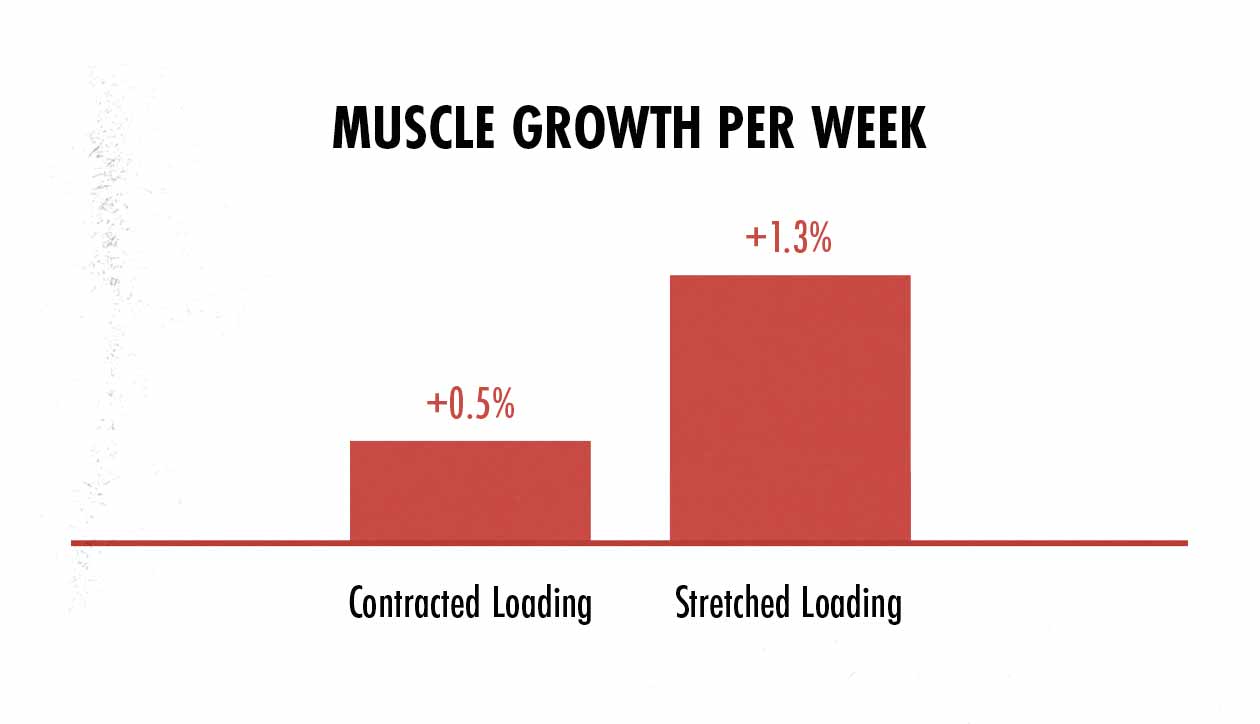

The differences in muscle growth are quite profound, too. If we look at a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of challenging our muscles at different lengths, we see that challenging our muscles in a stretched position stimulated nearly three times as much muscle growth as challenging our muscles in a contracted position.

Now, the catch is that we actually need to challenge our muscles in that stretched position. And as we’ve discussed above, it’s the strength curve of the lift that determines which parts of the range of motion are the most challenging. Fortunately, the bottom of the bench press, squat, and deadlift are all quite challenging. It works.

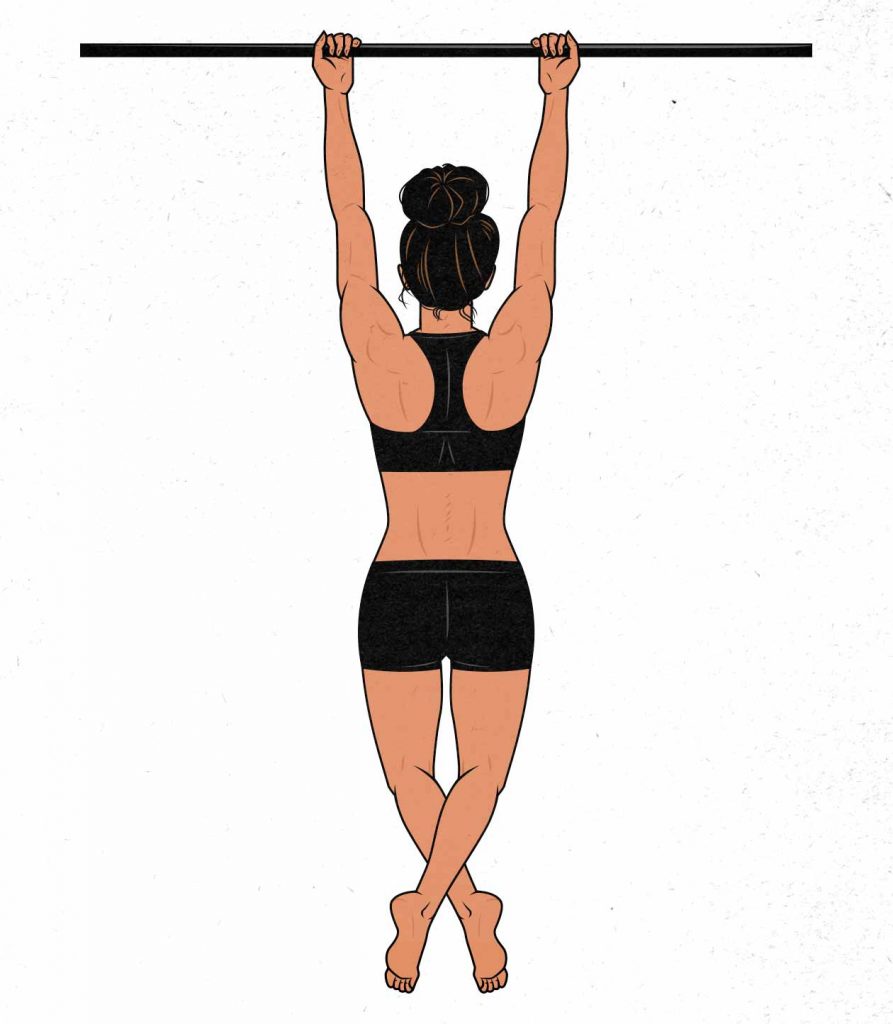

But with other lifts, things aren’t quite so rosy. Consider the chin-up. We get a full stretch on our muscles at the bottom of the lift, and that’s great, but that’s not the hard part of the lift. The sticking point is at the very top of the lift, as we try to bring our chests to the bar. That’s why it’s called a chin-up. If the chin-up doesn’t clear the bar, the rep doesn’t count.

Now, to be clear, chin-ups are still a great lift for building muscle. In fact, they’re one of the very best hypertrophy lifts. This is just one of many factors. But it makes a good case for also including the pullover, which loads our lats the heaviest when stretched, and the preacher curl, which loads our biceps when stretched.

Things get even worse for other lifts, such as the barbell row. Not only is the sticking point still at the very top of the lift, but our lats aren’t even stretched, nor worked through a large range of motion.

And this is the saving grace for some lifts. Consider the dumbbell fly. A lot of experts like to bash it because it’s disproportionately hard at the bottom, when our pecs are stretched. Joke’s on them, though. That’s where all the muscle is built!

For the most part, though, this research just confirms the traditional way that people train for hypertrophy. Most people know that they should squat, deadlift, and bench press fairly deep if they’re trying to build muscle. And all three of those lifts challenge our muscles the most when they’re at longer lengths. These are the traditional strength training lifts for a reason.

Still, we can use this principle to improve our lift selection.

- Probably best to avoid partial squats, above-the-knee rack pulls, and bench presses with a huge arch. By limiting the amount of stretch we get on our muscles, we limit the amount of muscle growth we stimulate.

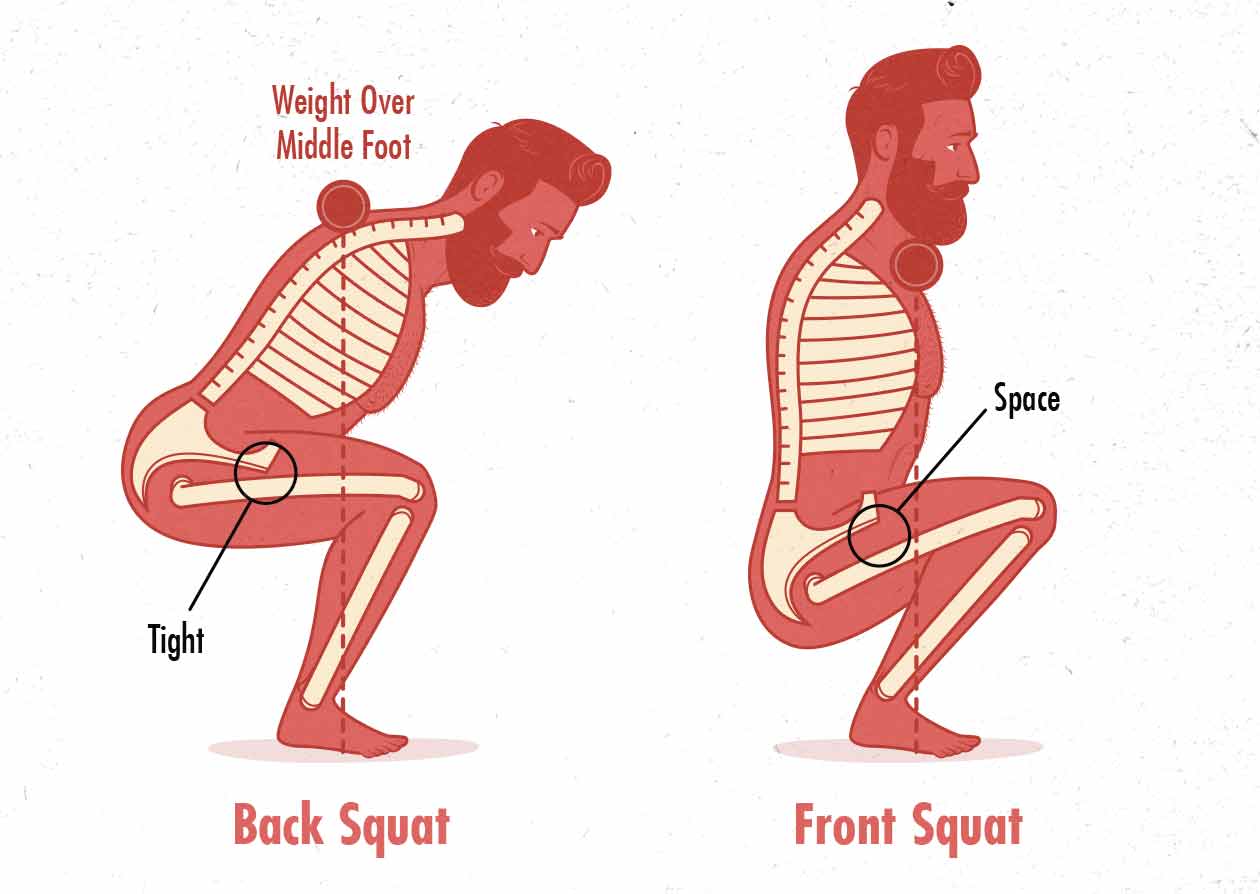

- We may also want to do front squats instead of back squats to get a deeper stretch on our quads.

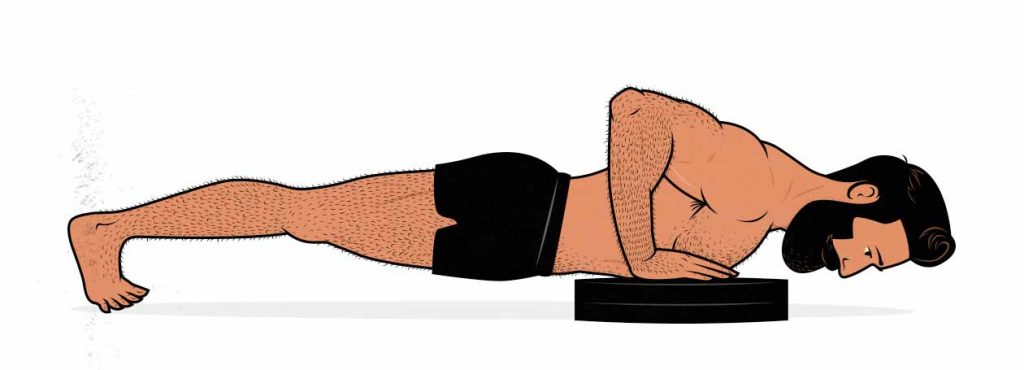

- Deficit push-ups are better than regular push-ups because they give our chests a deeper stretch.

- If you have good hip mobility, you might want to experiment with wide-grip deadlifts to get a better stretch on your hamstrings, glutes, and traps.

- If you have good overhead mobility, overhead extensions are better than triceps push-downs because your triceps are challenged in a stretched position.

This is also why training with just resistance bands isn’t great for building muscle. The variable resistance of resistance bands makes the lifts too easy when our muscles are in a stretched position, too hard when our muscles are in a contracted position. It’s the worst possible strength curve for building muscle.

Is a Large Range of Motion Best for Hypertrophy?

In most weight training programs, especially those focused on developing general strength, there’s an emphasis on using a large range of motion: we need to squat past parallel, bench all the way down to our chests, overhead press from our collarbones, do chin-ups from a dead hang, and deadlift from the floor. This emphasis on lifting with a full range of motion has its advantages, especially since we’re emphasizing the depth, not the contraction.

However, in severe cases, this emphasis on range of motion can lead to a psychological disorder called rage of motion, where lifters get angry whenever they see someone doing shallow squats, raised deadlifts, or failing to lock out their presses. But range of motion is just one factor. Just one tool that we can use. And for some people, there are good reasons to cut that range of motion short.

But let’s start with the advantages of lifting through a large range of motion. After all, there are indeed a few good reasons that lifting with a large ranger of motion can help us build more muscle:

- The further we need to lift the weight, the more work our muscles need to do, and that extra work—that extra volume—presumably stimulates extra muscle growth. This can also help us better improve our general fitness while lifting weights.

- Using a larger range of motion will often provoke muscle growth in more regions of our muscles, giving us more balanced muscle growth and more general strength.

- Using a larger range of motion will often force more muscles to contribute to the lift. For example, barbell curls with a full range of motion may stimulate more growth under our biceps (brachialis) and in our forearm muscles (brachioradialis), stimulating more overall muscle growth in our arms. We also see this with squats, where a larger range of motion produces equal growth in our quads, but extra growth in our adductors and glutes (study).

- Descending into a deeper stretch at the bottom of our lifts is a great way to stretch our muscles, which can make us more flexible. More importantly, we then need to lift the weight back up, strengthening our muscles through that entire range of motion, improving our mobility.

- A recent meta-analysis found that lifting through a larger range of motion tends to stimulate more muscle growth.

There’s some nuance to it, too, though. Sometimes lifting with a larger range of motion stimulates more muscle growth, other times not so much:

- Sometimes training with a larger range of motion can restrict blood flow into the muscles we’re working, boosting muscle growth. Other times, such as with triceps extensions, training with a partial range of motion is better for that (study). It depends on the lift.

- Sometimes a longer range of motion changes the leverage of the lift, making it harder on the muscles we’re trying to work. For example, going all the way to parallel while squatting requires stronger quads, but going even deeper does not.

- As we covered above, passive tension on our muscles is highest when they’re stretched. The deeper into a lift we go, the more we stretch our muscles under load, and so the more muscle growth we stimulate (study). This means that we should try to get a deep stretch on our muscles at the bottom of our lifts, but we don’t necessarily need to lock them out.

So overall, lifting with a large range of motion does tend to stimulate more muscle growth. However, it’s more important to get a deep stretch at the bottom of our lifts, not so important to lock our lifts out at the top, especially if that means removing tension from our muscles.

Is Constant Tension Good for Hypertrophy?

The next idea is the one that’s most popular among bodybuilders, especially those lifting with more of a classic style, with higher rep ranges, shorter rest times between sets, and more of an emphasis on getting a muscle pump. To get a better pump, it helps to keep constant tension on our muscles throughout the range of motion, and that often means avoiding relaxing a the bottom of a lift or fully locking out at the top. Everything becomes a partial.

As mentioned above, there’s some research showing that removing the easiest parts of a lift does a better job of restricting blood flow and thus results in more muscle growth. Therefore, it might sometimes be better to focus less on locking out each rep, more on keeping constant tension on our muscles and feeling a nice stretch at the bottom, especially when lifting in higher rep ranges.

The only time we’ve seen this idea proven is with triceps extensions, where the only thing locking out does is give our triceps a break. That might apply equally to:

- The squat, where fully locking out each rep gives our hips, quads, and upper backs a break.

- The overhead press, where locking out each rep takes the load off of our shoulders and triceps.

- The bench press, where locking out our reps takes the load off of our chests, shoulders, and triceps.

- The Romanian deadlift, where we’d be giving our hamstrings and hips a break (although not our traps or forearms).

It may also mean that we don’t want to fully relax at the bottom of our biceps curls, chin-ups, and deadlifts. We do want to stretch out at the bottom, but we don’t necessarily want to relax there.

Keeping constant tension on our muscles while lifting does seem to improve muscle growth, but we should still make sure to get a deep stretch on our muscles at the bottom of our lifts.

Are Heavy Partials Good for Hypertrophy?

The amount of muscle we can build seems to be linked to the amount of bone mass we have and how strong our connective tissues are. There isn’t that much research on this yet, so it’s certainly still speculative, but it could be that developing stronger bones could help us build more muscle.

Lifting weights in any rep range can strengthen our bones, at least to a point, but the type of lifting that’s best for improving our bone health is the heavy stuff in the 1–5 repetition range (85% of 1RM or higher). That means that if we have some heavy deadlifting, overhead pressing, and chin-ups in our workout routines, we’re probably covered, but it’s possible that we could take that effect further by doing even heavier partials, such as raised deadlifts or rack pulls. It wouldn’t be better for short-term muscle growth (and would probably be worse) but it might help to strengthen our bones and connective tissues to the point where we can ultimately gain more muscle. As a result, it might be a good strategy for people who fear that they’re approaching their genetic muscular potential.

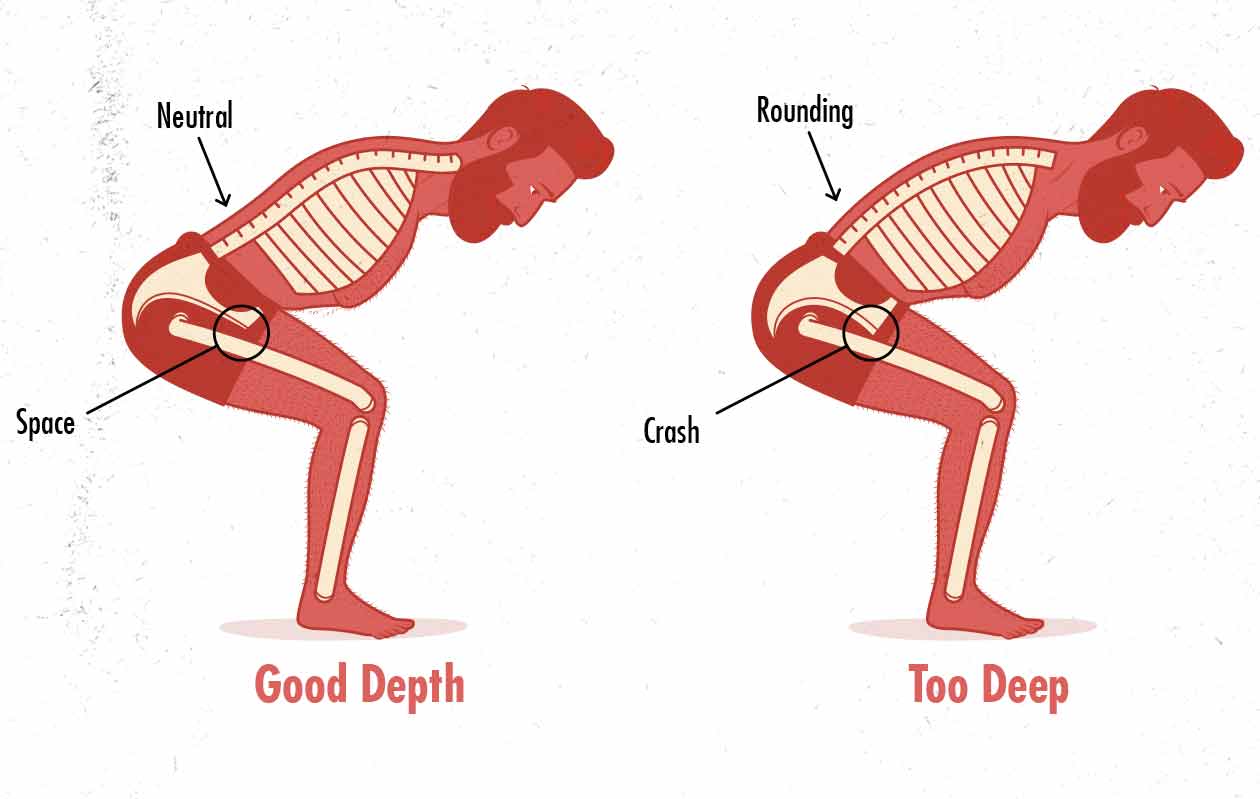

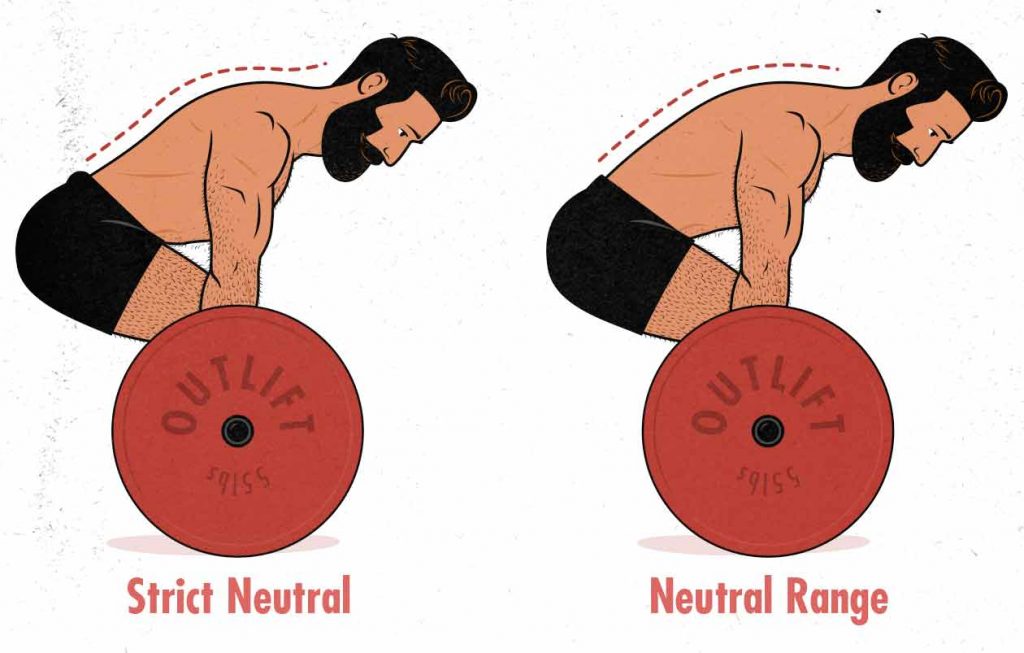

A more compelling reason to cut our range of motion short is that lifting with an arbitrarily large range of motion can make a lift more dangerous. For example, let’s consider the deadlift, where some people are limited by the range of motion in their hips:

In this case, going deeper isn’t improving the range of motion in our hamstrings or hips, it’s just forcing us to bend our lower backs, making our deadlifts needlessly more dangerous.

The same thing can happen with squats—especially low-bar back squats—where it’s often hard for people to even get down to parallel without needing to bend in their lower backs:

So in these cases, we either want to choose different variations of the lifts that free up more hip space, such as front squats instead of back squats, or trap-bar deadlifts instead of barbell deadlifts, or we want to stop our range of motion at the point where our spines are still in the neutral range, like so:

If that means avoiding wide-grip deadlifts and ass-to-grass squats, so be it. In some of us, that may even mean avoiding deadlifting from the floor or squatting to parallel. That may sound blasphemous, and I’m sure it is, but if the extra range of motion is coming from joints that we aren’t trying to work, then we’re defeating the purpose, and potentially increasing our risk of injury for no reason. We might also be putting ourselves into weaker positions, needlessly limiting the amount of weight we can lift.

When it comes to training our spinal erectors, we usually want to train them isometrically—no range of motion at all. I didn’t really think of that until just now, but I suppose most of us train our spinal erectors exclusively with heavy partials. And that’s great.

Heavy partials don’t tend to be great for stimulating muscle growth, but they do put more stress on our bones and connective tissues, so every once in a while they can be a useful addition to a hypertrophy routine.

Key Takeaways

Lifting with a larger range of motion does usually stimulate more muscle growth (study), especially if that extra range of motion comes from sinking deeper into our reps and getting a better stretch on the muscles we’re working. That’s even more true if that bottom of the range of motion is a challenging part of the lift, such as in the bench press, squat, and deadlift (but not the chin-up or row).

However, there are also some benefits to keeping constant tension on our muscles while lifting, and sometimes that can mean lifting with a shorter range of motion. An obvious example of that is avoiding a full lockout when doing skull crushers, but it may also help to avoid full lockouts with some compound lifts, such as the bench press, squat, overhead press, and Romanian deadlifts.

Finally, some muscles benefit from being trained with a smaller or even non-existent range of motion. Squats and deadlifts are considered great lifts for our spinal erectors despite them not going through any (intentional) range of motion at all. And because it’s usually best to avoid back rounding, that might mean we need to limit the depth on our squats or deadlifts.

Putting this into practice, if we’re trying to bulk up our biceps, we might start our workouts off with some heavy chin-ups, not really putting that much emphasis on keeping constant tension on our muscles, focusing more on lifting heavy, explosively, and with good technique through a full range of motion. Afterwards, we might do some barbell or preacher curls, this time making sure to keep constant tension on our biceps throughout the set, even if that means cutting the range of motion a little bit short at the top. That way we’re getting the best of both worlds.

Or if you want a customizable bulking program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. If you liked this article, you’ll love the full program.

Shane and Marco,

Assume Sets A and B for the same exercise.

Both sets last the same amount of time, say 30 sec.

Weight selection for each set is such that you have “2 reps in the tank” by the end of the set.

Which set would stimulate more muscle growth?

Set A where all reps were full range of motion?

Set B where all reps where in the hardest half of the range of motion?

Thank you,

F

That’s an interesting question.

There are other lifts where the hardest part of the lift tends to be at shorter muscle lengths, such as with the chin-up and row. In those cases, no, that wouldn’t help. Better to include the deeper part of the range of motion, get a good stretch on the muscles.

With lifts that are harder when they’re deeper, when you shrink the range of motion, the sticking point can change. So, for instance, if you squat with a partial range of motion, only coming a quarter of the way down, then the lowest part of the squat is the sticking point—the hardest part of the rage of motion—but it’s still a shortened range of motion. In this case, even though we’re lifting more weight, we see less growth (presumably because we’re training at shorter muscle lengths).

I think what you’re asking, though, is if we did little hover-reps around the sticking point of a full range-of-motion squat, which would be around parallel, would it work better than including the ass-to-grass and lockout portions? We’d drop down to an inch below parallel, lift to an inch above parallel—that kind of thing? That’s not really done, and I’m not sure it would be helpful, but we do see people pause at the sticking point—pause squats. Is that ideal for building muscle? It doesn’t appear to be so.

Some lifts lend themselves to doing mini reps at deep muscle lengths, though. You could do push-ups going all the way down, only coming up a few inches, and then going all the way back down again. That way you’d be training your chest at long muscle lengths, which is good. You’d miss out on some triceps stimulation, though. If you watch some pro bodybuilders lift, though, you’ll see that kind of thing. They’ll hop on a chest press machine, say, and blast their chests with these deeply stretched mini-reps. Jay Cutler trains like that sometimes. Is that more effective for bulking up the chest? Maybe! I’m not sure.

I’m sorry I don’t have a better answer for you.

Hey, can you explain why restricting blood flow is better for muscle growth?

Hey Ashhad,

When we flex our muscles, they get bigger, which compresses the capillaries surrounding them, restricting blood flow (acute intramuscular hypoxia). Then, when we stop flexing our muscles, the blood rushes back in, bringing a bunch of metabolites along with it, and stimulating muscle growth via metabolic stress. It seems that this increases protein synthesis, growth hormone, epinephrine, lactate, and mTor signalling. Some research shows that when we keep constant tension on our muscles, we restrict that blood flow for longer, and so we get a larger benefit afterwards.

That’s the idea, anyway. Even the researchers don’t seem to have a full understanding of this yet. But there is some research showing that constant tension can increase muscle growth, so there might be something there.

Thanks for the reply. I appreciate it.

My pleasure, man 🙂

I have bad wrists, which is why I want to use lighter weights. Bench pressing with the bar closer to my chest means I can reach failure at a lower weight. It also means my wrists won’t go through as wide a range of motion. I know I have to strengthen them with full range later, but I see this as good for rehab. The lock-out is a resting place for me.

To work my chest with contracted muscles, dual cable flies allow lighter weight to work just as hard if not harder.

For triceps, I do one-armed dumbbell extensions at 2 different angles.

I was just curious if I was failing to build anything up. Maybe the cartilage in the locked position. I could do a separate set of lockouts just for that.

Benching with a deep range of motion is great for building muscle. When the bar is close to your chest, your pecs are under a deeper stretch. That’s where most of the muscle growth is stimulated. You aren’t missing out on any chest growth by avoiding the lockout. The lockout can be good for working the triceps, but you’ll do a better job of building bigger triceps with exercises that use a deeper range of motion (such as skull crushers and overhead extensions).

You probably don’t need to do exercises that emphasize the contracted position. I think it’s a myth that has survived because it feels hard, scores well on muscle activation tests, and gives a good pump. But most research shows that exercises that emphasize the contraction are very poor for actually gaining muscle size and strength. It’s the deep part of the range of motion you want to focus on.

I would use dumbbell flyes instead of cable flyes. You’ll work your pecs harder in a deeper stretch.

If your wrists struggle with heavier weights, you can also lift in higher rep ranges. Instead of doing sets of 5, you can do sets of 15.

Let me ask Marco if he has any more advice for bad wrists.

This was the video I forgot to link!

What does this exercise do exactly?

Hey Aaron, Marco here!

How long have your wrists been giving you trouble? If it’s due to a traumatic injury, sometimes that means modifications are in order. If it’s more of a thing where certain moves have always bothered you, it’s possible it could be a mechanics thing. If that’s the case, sometimes it helps to start by looking at the pelvis and ribs.

An exercise like this might be a good place to start.

If it’s more recent, it could be due to increasing the weight or volume too quickly. Sometimes it’s a combination of all three!

Either way, if it’s stopping you from enjoying your workouts or challenging yourself as hard as you like, it might be worth exploring a bit more.

4jopfo

Why would bench pressing with a huge arch stretch the chest muscles lesser? I thought the opposite when doing DB bench press. The more I arch, the higher my chest goes and bringing the dumbbells below chest height will become easier which will stretch the pecs even more.

You also made a video talking about why arching on bench press has its advantages and no downsides. Am I missing something here?

This is an older article. The video is more recent and represents my current thinking.

But you’re talking about the dumbbell bench press, which is a different beast. You can bring the dumbbells past the level of your chest, allowing you to get a nice, deep stretch either way. I imagine a modest arch is good with few downsides, especially if it feels better or helps you lift more weight. I suspect a bigger arch might be better for your lower chest, but a big arch is hard, and most people don’t use big arches, even when they try. Not arching is fine, and might get your upper chest a little more, maybe, but you’d be better with an incline bench press for that anyway.

Thanks for the clarification! Also, I have heard that NOT arching on the bench press works your serratus anterior muscles harder as compared to benching with an arc. Is this true?

I’m not so sure about that. Are you talking about retracting your shoulder blades? It’s true that if you let your shoulder blades move during the bench press, then you can do a better job of stimulating your serratus anterior. Your shoulder blades will still be pressed into the bench, though, which can make that awkward. If you want to train your serratus anterior, I would use push-ups, deficit push-ups, dips, and overhead presses.

You can mix the different exercises together, too. You could do some heavy benching with retracted shoulder blades and an arch. Then you could do some push-ups or overhead presses, letting your shoulder blades move freely.