The Hypertrophy Training Guide: How to Lift for Muscle Size

Hypertrophy training is designed specifically for stimulating muscle growth. It’s by far the best style of training for building muscle. Bodybuilders use it to build more aesthetic physiques. Powerlifters use it to build bigger muscles with greater strength potential. When Marco was coaching professional and Olympic athletes, he’d use it to help them gain functional muscle mass.

Hypertrophy training can’t be bent into the shape of any muscle-building goal. You can use it to get bigger, look better, gain strength, improve your athletic performance, or improve your health.

In this guide, we’ll teach you the main principles of building muscle, then how to min-max every variable of your workout routine, including how often to work out, which exercises to focus on, how many reps and sets to do, how hard to train, and how long to rest. By the end, you’ll know exactly how to train for muscle growth.

- What is Hypertrophy Training?

- Myofibrillar Versus Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy

- Fast-Twitch and Slow-Twitch Muscle Fibres

- A Balanced Approach to Muscle Growth

- The Principles of Hypertrophy Training

- How to Train for Muscle Growth

- The Power of Compound Lifts

- The Purpose of Isolation Lifts

- Balancing Compound & Isolation Lifts

- Which Exercises Are Best for Building Muscle?

- Different Goals Call for Different Exercises

- Doing Enough Repetitions Per Set

- Doing Enough Challenging Sets

- Training Often Enough

- Training Hard Enough

- Getting Enough Rest Between Sets

- Making Your Workouts More Efficient

- Summary

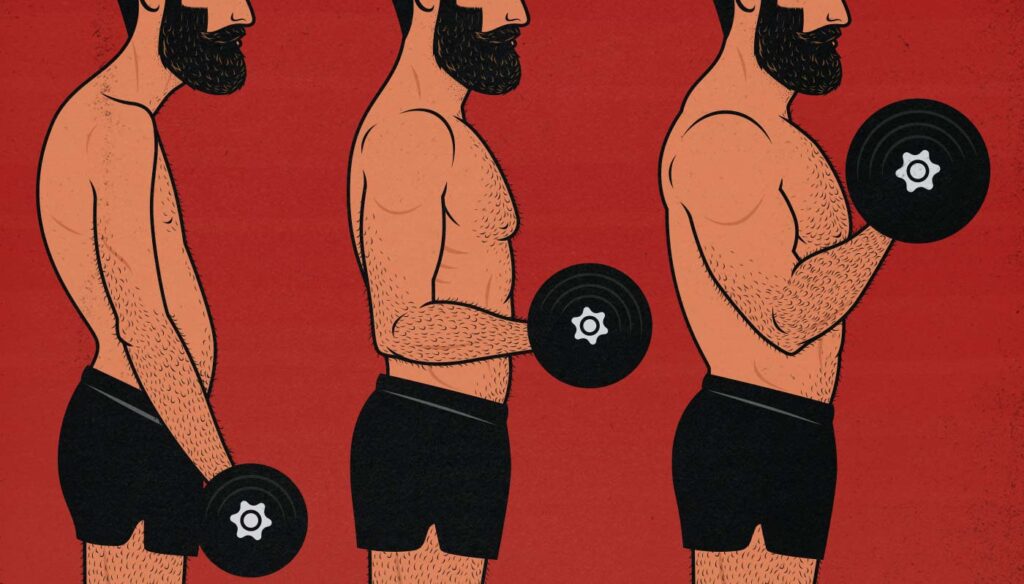

What is Hypertrophy Training?

Muscle hypertrophy means muscle growth, so hypertrophy training is the style of training designed to stimulate muscle growth. Some people call this style of training “bodybuilding,” but bodybuilding can involve various other things: dieting, posing, and so on.

Plus, you could just as easily use hypertrophy training to help you get stronger, healthier, or more athletic:

- Strength: the bigger your muscles are, the greater their strength potential is. That’s why strongmen, powerlifters, and all other types of strength athletes use hypertrophy training to build bigger muscles.

- Athleticism: the bigger your muscles are, the more explosive power they can produce. And the bigger you are, the more momentum your body will have. That’s why Olympic weightlifters, most athletes, and most fighters are interested in building muscle.

- Aesthetics: one of the best things we can do to improve our appearance is to build bigger muscles, especially in our upper bodies. In fact, our muscularity may be the most important part of having an attractive physique (study).

- Health: having more muscle mass relative to our fat mass improves a number of our health markers, ranging from blood sugar control to cardiovascular health, and in so doing, reduces our risk of all-cause mortality (study, study, study).

Myofibrillar Versus Sarcoplasmic Hypertrophy

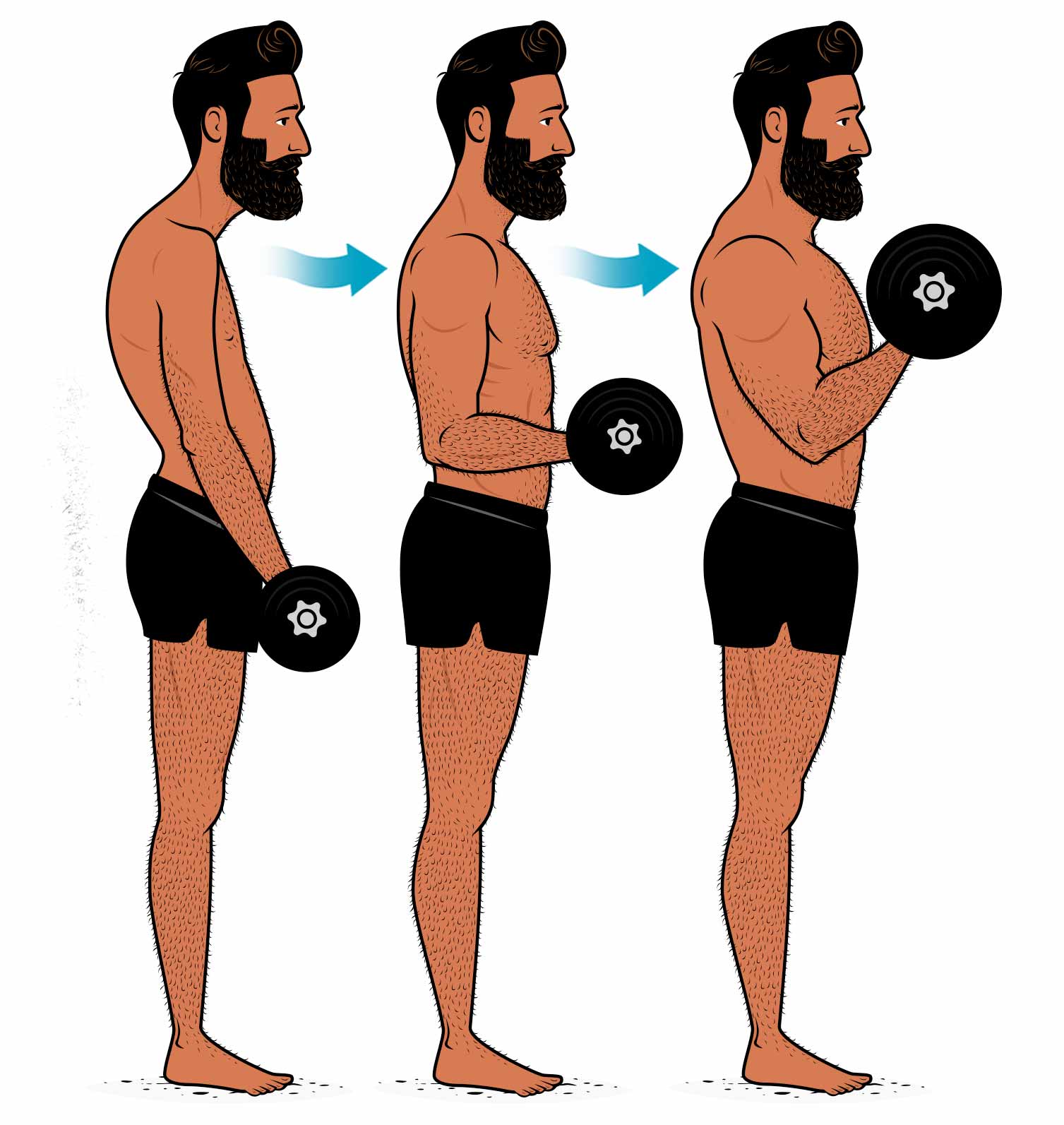

Before we talk about how to stimulate muscle growth, it helps to know at least a little bit about what’s going on under the hood. The first thing that’s often talked about with muscle hypertrophy is the two ways in which our muscle fibres grow:

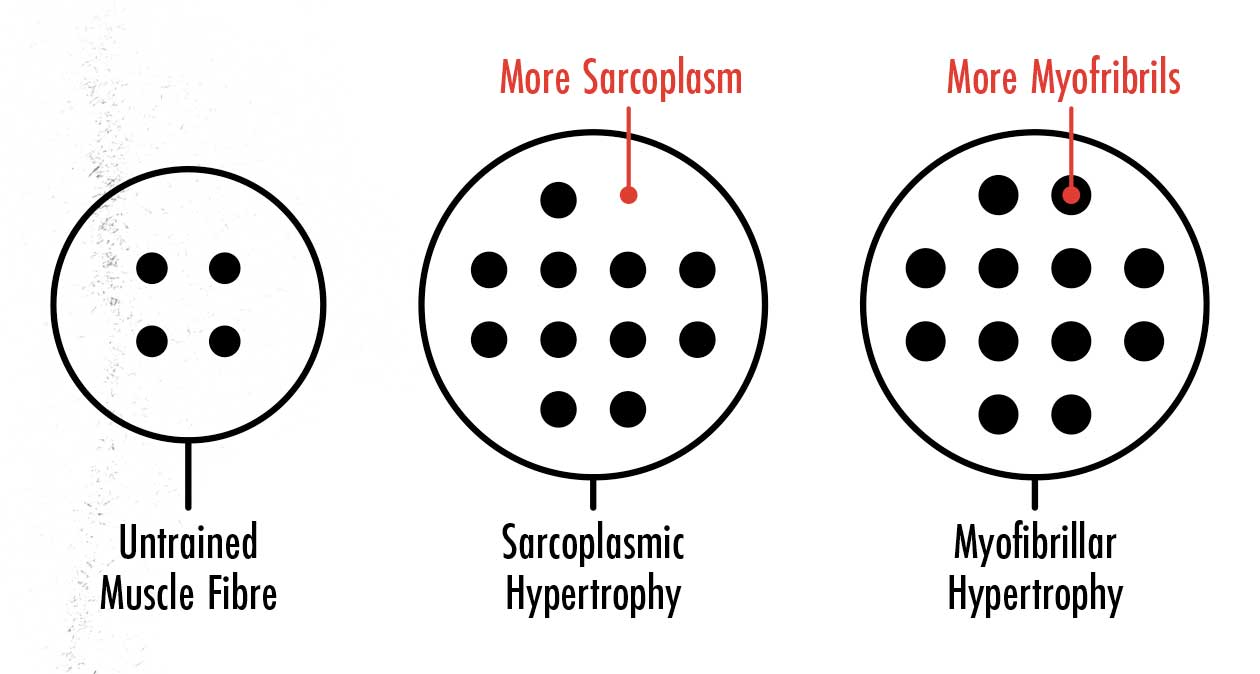

- Myofibrillar hypertrophy: this is when the myofibrils inside our muscle fibres grow bigger, allowing our muscles to produce more force, allowing us to lift more weight for a single repetition.

- Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy: this is when the sarcoplasm surrounding the myofibrils expands, giving us more fuel and growth potential, and allowing us to do more repetitions (study).

This diagram can make it seem like there’s hardly any difference between sarcoplasmic and myofibrillar hypertrophy, and that’s true. As our muscles grow bigger, there’s always a balance between the myofibrils and sarcoplasm—usually about 80% myofibrils and 20% sarcoplasm.

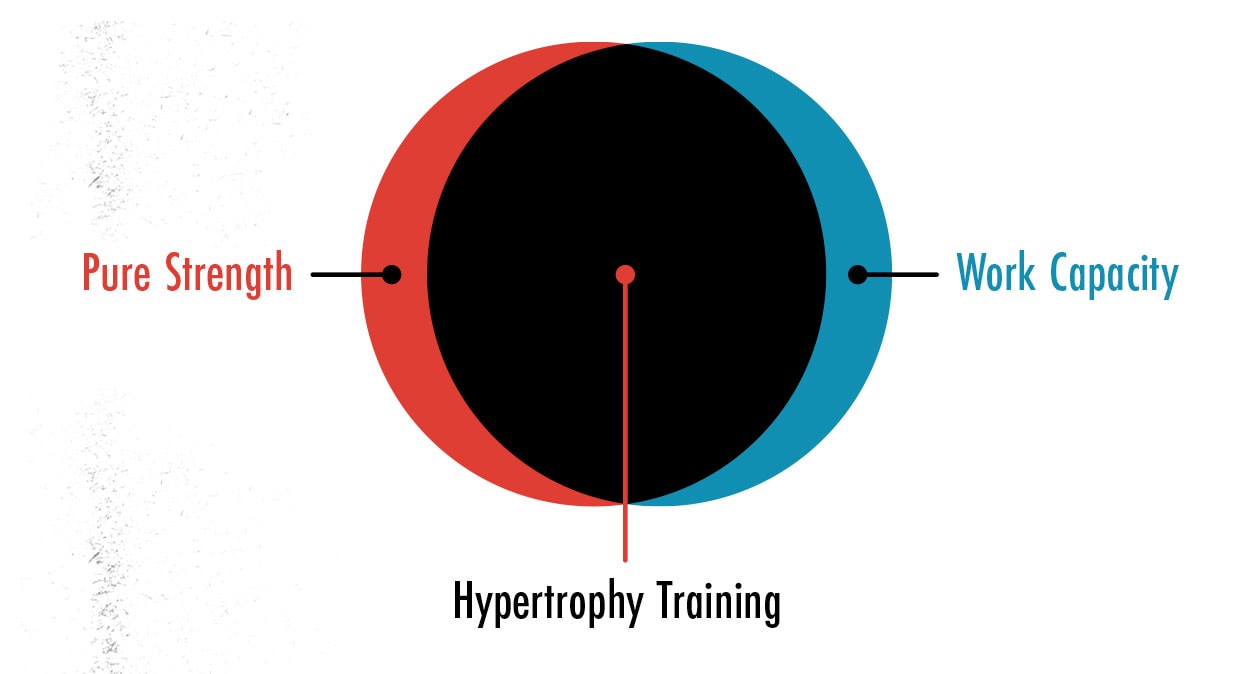

Heavier training might stimulate a bit more myofibrillar hypertrophy, making us stronger, whereas high-volume bodybuilding may yield a little more sarcoplasmic hypertrophy, giving us greater work capacity (study, study).

Some advocates of certain styles of training put a huge emphasis on the different types of muscle hypertrophy, but both types of hypertrophy make our muscles bigger and harder, and both are valuable adaptations.

Myofibrillar hypertrophy lets us lift more weight for a single repetition, improving our 1-rep max. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy lets us lift weights for more repetitions, improving our rep maxes. With hypertrophy training, we want both types of muscle growth, so we train directly for both.

Fast-Twitch and Slow-Twitch Muscle Fibres

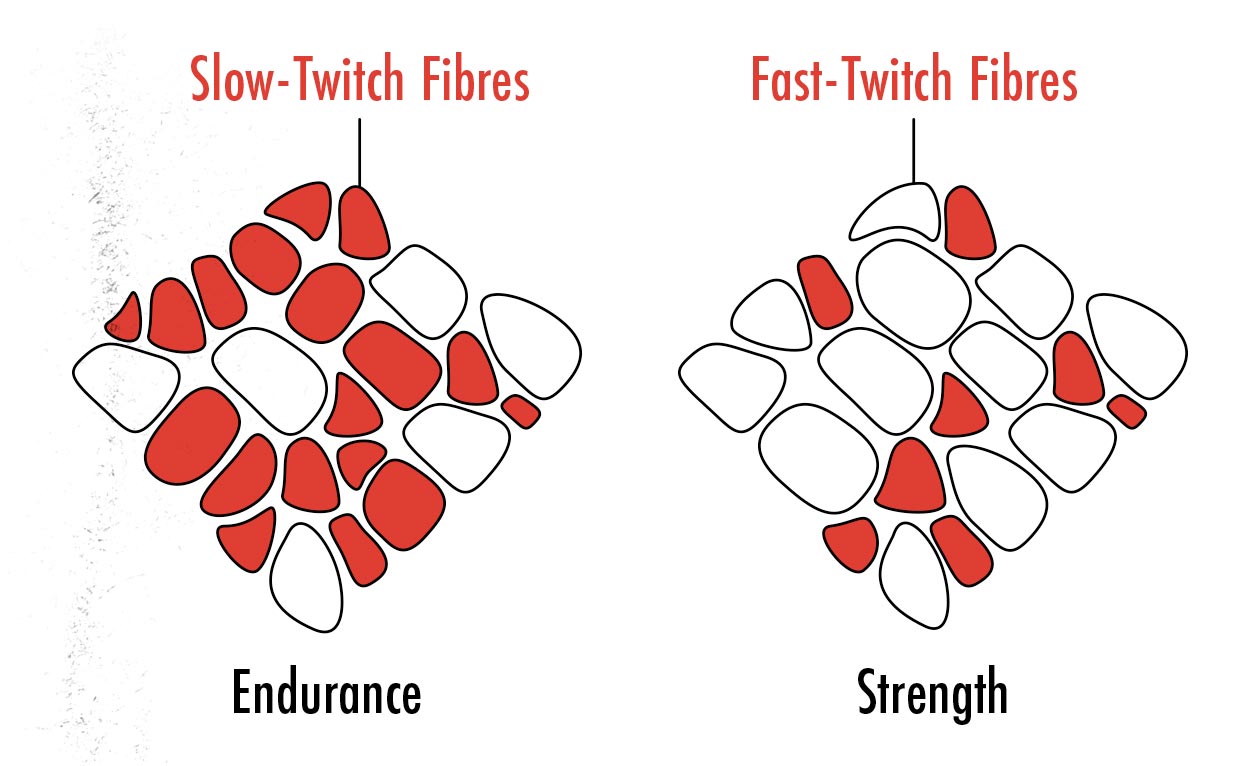

The same thing goes with our muscle fibres. We have fast-twitch muscle fibres that are bigger and stronger, and we have slow-twitch fibres that have greater endurance and more blood vessels (which is why they’re red). Different people and different muscles have varying proportions of each type of muscle fibre. We want to hypertrophy all of our muscle fibres, so we train for both strength and work capacity.

Hypertrophy training is a hybrid approach, building muscle by developing both muscular strength and work capacity. Powerlifters are known for lifting heavy things for fewer reps, stimulating muscle growth by putting a ton of tension on their muscles. Bodybuilders are good at feeling the burn and getting a pump, stimulating muscle growth with metabolic stress. We want to build muscle in both ways, so we do both.

As a welcome bonus, since we’re lifting heavy weights through a large range of motion for a moderate number of reps, hypertrophy training has quite a lot in common with high-intensity interval training (HIIT), making it decent for improving cardiovascular fitness (study).

A Balanced Approach to Muscle Growth

Because building muscle is so good for so many things, hypertrophy training is the best default way of lifting weights. Powerlifters start with hypertrophy training to build bigger muscles, then specialize in heavy strength training. Athletes start by building bigger muscles and then focus on developing power. But if you aren’t a powerlifter or athlete, there’s nothing wrong with focusing purely on building muscle.

So when building a hypertrophy program, we don’t need to worry about which style of training develops slightly more power, work capacity, fast-twitch muscle fibres, or 1-rep max strength. And we aren’t locked into doing specific lifts.

Instead, we can focus purely on which methods yield the most muscle growth, which lifts are best for our joints and health, and which muscles we’re most eager to grow.

The Principles of Hypertrophy Training

Resistance Training: Challenging Your Muscles

Most types of exercise have at least a bit of overlap. When we go running, the muscles in our legs will grow a little bit bigger and stronger. And when we lift weights, we’re often left feeling tired and out of breath, which is good for our cardiovascular systems. But there’s no doubt that to build a serious amount of muscle, we need to train for it directly.

At one end of the spectrum, we have endurance training, where the idea is to raise our heart rate, challenge our cardiovascular system, and improve our general fitness. Think of activities like jogging, biking, and burpees. At the other end of the spectrum, we have resistance training, where the goal is to challenge our muscles, tendons, and bones, making them bigger, stronger, and denser. Resistance training is what builds muscle, so that’s what we’re focused on.

There are a few different types of resistance training. You can train to become stronger for your size (strength training), to develop more explosive power (Olympic weightlifting) or to build more muscle mass—hypertrophy training. And even within hypertrophy training, we can use several different tools, ranging from exercise machines to dumbbells to barbells. Resistance bands and bodyweight exercises can work, too, but they make it somewhat harder to build muscle.

I would agree with your general recommendations of free weights and machines for hypertrophy, with bands and bodyweight working in a pinch.

Eric Helms, PhD

The most important thing, though, is to train in a way where our muscles limit us. For instance, if you load up a barbell with a weight you can only lift for 8 repetitions, then your muscles will give out before your cardiovascular system limits your performance. Now compare that against something like a burpee. It’s a combination of a push-up and a squat, both of which can be good exercises for building muscle. But when the two are combined, it becomes a cardio exercise.

To ensure that you’re challenging your muscles, focus on exercises that are simple and stable, and that are done heavy enough that your muscles give out before your fitness does. Squats done for sets of 6 repetitions, the bench press for sets of 8, biceps curls done for sets of 10. That kind of thing.

Progressive Overload: Growing Bigger & Stronger

Once we’re doing exercises that challenge the strength of our muscles, the next thing we need to do is make sure we’re challenging them enough. We need to work them hard enough to provoke an adaptation—to grow back bigger and stronger than they were before. And because our muscles keep growing bigger and stronger, we need to keep challenging them with progressively heavier weights.

The idea of progressive overload is best illustrated by the story of Milo of Croton, the ancient Greek wrestler. He started by picking up a calf and carrying it up and down the street. The calf was small, but so were Milo’s muscles, and so it was enough to challenge him. His muscles grew a little bit bigger every day, and so did the calf, ensuring that his muscles were always challenged. By the time the calf grew into a bull, Milo had become the strongest wrestler in Greece.

As you can see, progressive overload is both the cause and the result of building muscle:

- Muscle growth allows progressive overload: if our muscles have grown bigger, that means we can lift heavier weights. Muscle growth is what allows us to outlift ourselves.

- Progressive overload causes muscle growth: now that our muscles are bigger, to continue challenging them, we need to lift heavier weights. Lifting heavier weights is what stimulates more muscle growth.

It’s a sort of chicken and egg riddle. One causes the other, allowing us to grow gradually bigger and stronger over time. And sometimes, that can cause hiccups. Let’s consider two common examples.

- Not enough progressive overload: let’s say that during your first workout, you bench press 135 pounds for 8 repetitions, failing midway through your ninth rep. That’s enough to stimulate quite a lot of muscle growth. So you go home, eat plenty of protein and food, and get a good night’s rest. Two days later, you show up to your next workout a little bit bigger and stronger than last time. You load up the bar with 135 pounds again, and this time the 8 repetitions feel a bit easier. Maybe you could have gotten 10 repetitions. Great, that’s still challenging. You’ll still stimulate some muscle growth. So you go home, eat and rest, and come back two days later. This time, when you lift 135 pounds for 8 repetitions, it’s too easy. You could have gotten 12 reps. Now you aren’t stimulating muscle growth anymore. There wasn’t enough progressive overload. To solve this problem, always add a bit of weight or try to get an extra rep. You don’t need to hit failure, but always try to lift a bit more than last time.

- Not enough muscle growth: let’s go back to the beginning. During your first workout, you bench press 135 pounds for 8 repetitions. That’s enough to stimulate muscle growth, but you don’t eat enough to build muscle, and so when you come back two days later, you still can’t get a ninth rep. So you grind and you push, knowing that you need to lift more weight. But you can’t. You can’t force progressive overload. To lift more weight, you need more muscle mass. And in this case, because you haven’t built any muscle, 8 reps is still challenging. It will still stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth. So lift those 8 reps, go home, and eat more protein, eat more food, and get more sleep. That way you can show up to your next workout bigger and stronger than last time.

So progressive overload is two things:

- We need to challenge our muscles enough to stimulate muscle growth, which requires gradually adding weight to the bar.

- And then we need to give our muscles what they need to grow: enough protein, enough food, and enough rest. That’s what allows us to lift more weight.

In this article, we’re only talking about hypertrophy training. We’re talking about how to stimulate muscle growth with our workout routines. But the other half is just as important.

For more, we have a full article on progressive overload.

How to Train for Muscle Growth

The Power of Compound Lifts

Everyone has a slightly different idea of which lifts are best, and depending on whether you’re using dumbbells, barbells, or exercise machines, they can vary. But for gaining muscle mass, these five compound lifts tend to make the best foundation:

- The squat: the knee lift, designed to bulk up your quads. But it will also build muscle in your hips, back, and core. Think of goblet squats (for beginners), front squats, split squats, and high-bar back squats.

- The bench press: the chest lift, designed to bulk up your pecs. But it will also build muscle in your shoulders and triceps. Think of push-ups, dumbbell bench presses, and barbell bench presses. If you’re a rebel, you might even include dips here.

- The deadlift: the hip lift, designed to bulk up your glutes, hamstrings, and lower back. But it will also build muscle in your upper back and forearms. Think of Romanian deadlifts, conventional deadlifts, and sumo deadlifts.

- The overhead press: the shoulder lift, designed to bulk up your deltoids. But it will also build muscle in your upper back, triceps, and abs. Think of incline bench presses, dumbbell overhead presses, and the barbell “military” press.

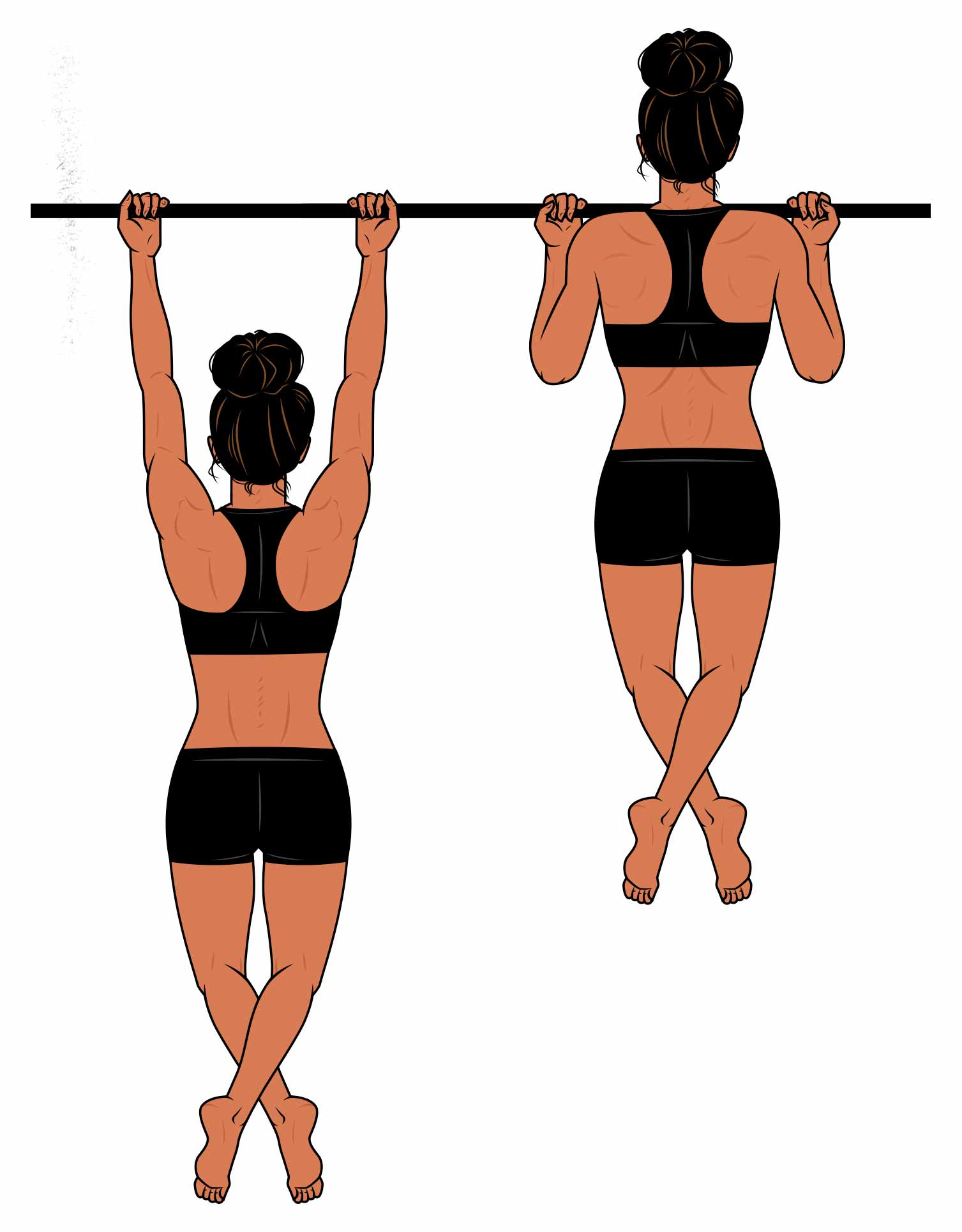

- The chin-up: the back lift, designed to bulk up your entire upper back. But it will also build muscle in your biceps and abs. Think of chin-ups with an underhand or neutral grip, done on a straight bar, angled bar, or using gymnastic rings. Or pull-ups with an overhand grip. Even rows can serve in a pinch.

These five exercises stimulate a ton of overall muscle growth, allowing you to bulk up all of the biggest muscles in your body. You can do them with dumbbells or barbells. Some people even use machines. If you can get strong at them, you’ll build an impressive physique, guaranteed. And we can do even better!

The Purpose of Isolation Lifts

It’s common to hear that focusing on the big compound lifts is all you need, especially for beginners. That’s technically true. You can gain a ton of muscle mass by doing compound lifts. You don’t need anything more. But you might want more. Here’s why:

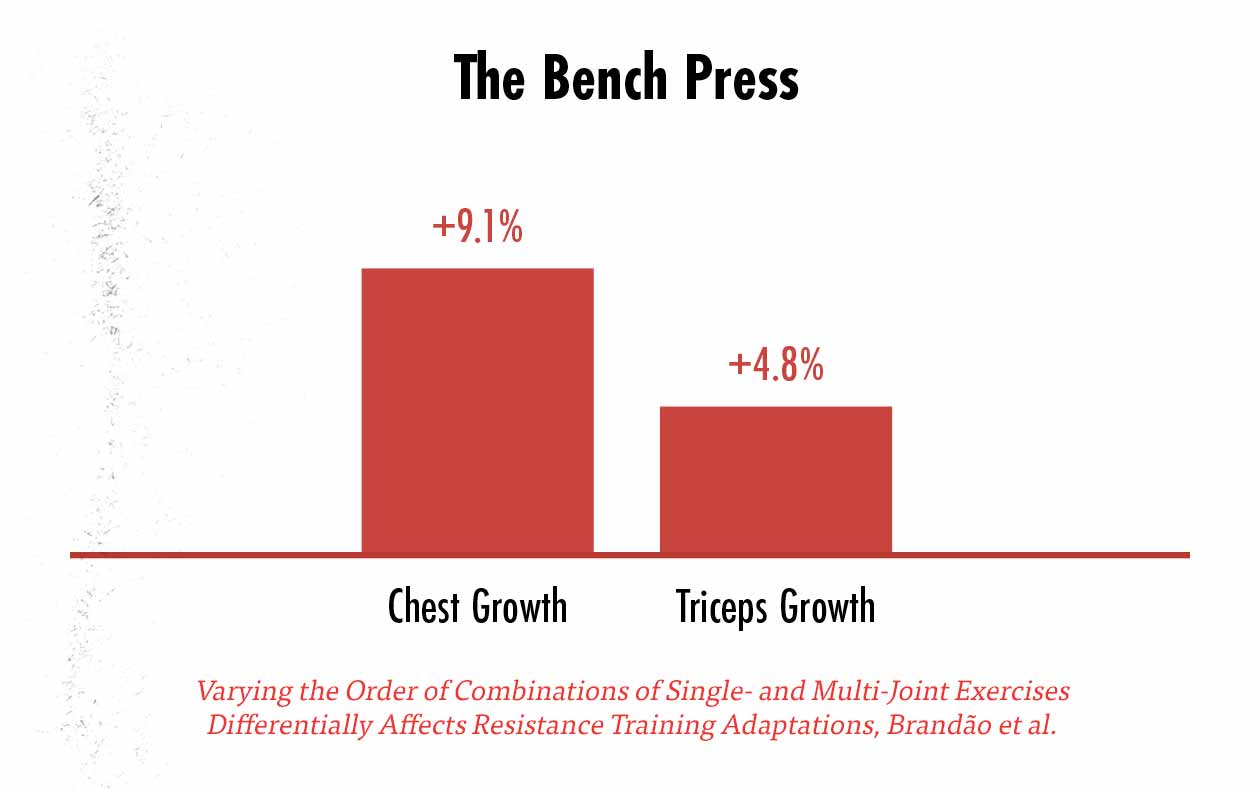

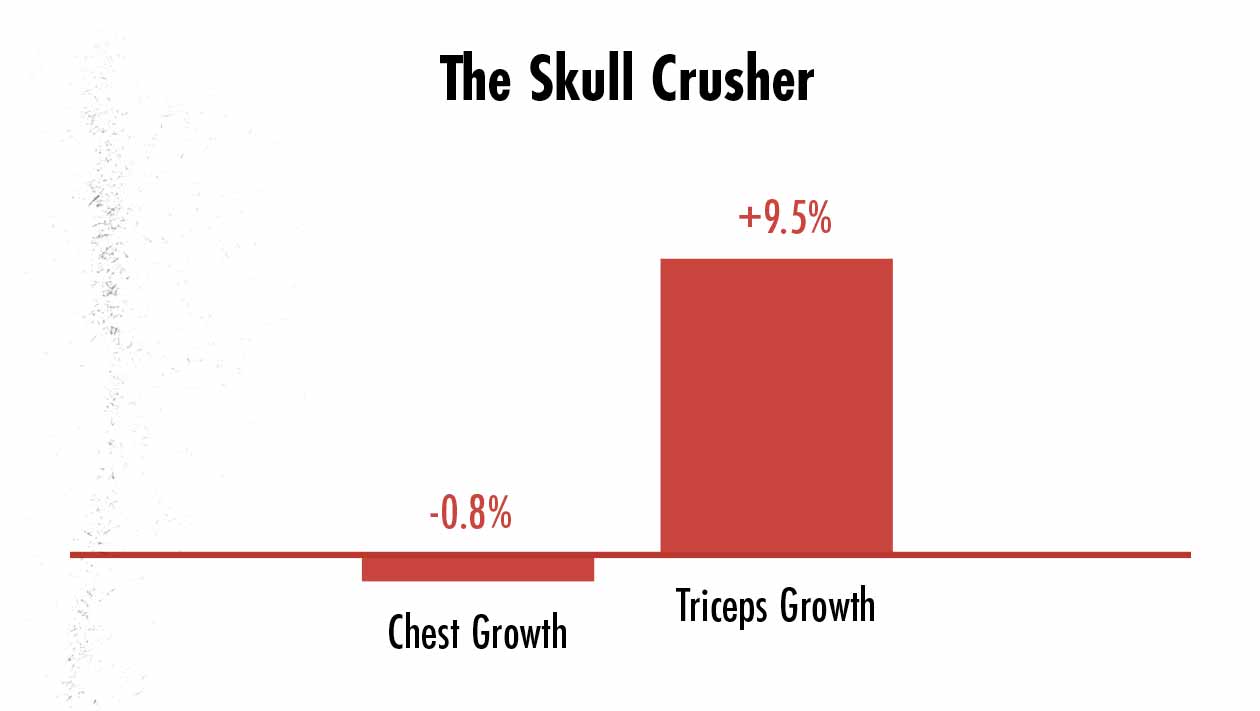

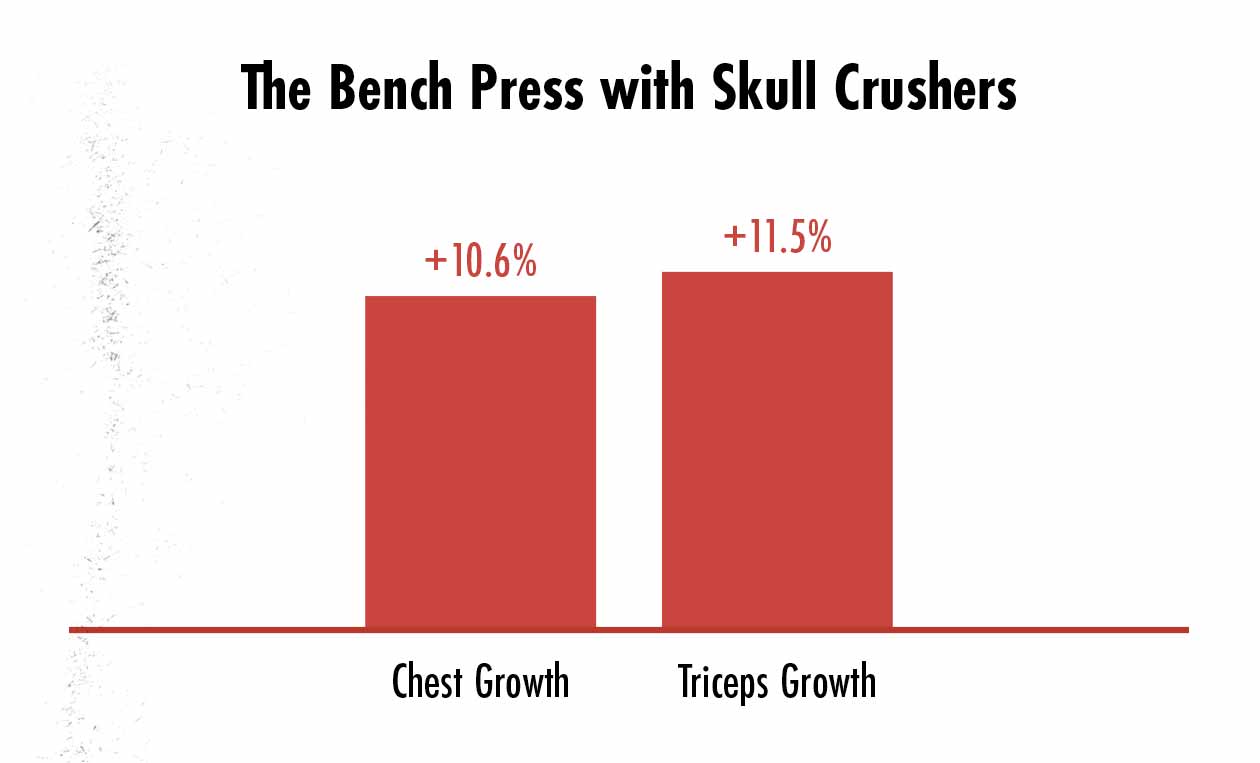

If you only do the bench press, your chest will grow twice as fast as your triceps (study). And it’s not hard to see why. When you do the bench press, you’re doing a movement that your chest is best at. It’s your chest that dominates the lift, your chest that’s brought closest to failure, and so it’s your chest that receives the best growth stimulus. It’s a compound lift, but the main muscle being worked is the chest.

Your triceps, on the other hand, are better suited to extending your elbows. That’s why if you do skull crushers, all of a sudden we see perfect triceps growth… at the cost of your chest. After all, the skull crusher doesn’t work your chests at all. It’s a small isolation lift.

To develop all of our muscles in a balanced way, we need to use a mix of both compound and isolation exercises. By doing both the bench press and skull crushers, we get balanced growth in both our chests and triceps.

Here are the muscles that benefit the most from isolation lifts:

- Biceps benefit from biceps curls.

- Triceps benefit from triceps extensions.

- Side delts benefit from lateral raises.

- Rear delts benefit from rows or face pulls.

- Neck muscles benefit from neck curls and extensions.

- Forearm muscles benefit from reverse curls and forearm curls.

- Calf muscles benefit from calf raises.

- Hamstrings benefit from leg curls.

- Quads benefit from leg extensions (for the rectus femoris).

- Abs benefit from crunches, reverse crunches, and planks.

- Upper chest benefits from close-grip or incline pressing.

Balancing Compound & Isolation Lifts

With that said, you don’t need to do isolation lifts for all of those muscles, let alone every workout. Compound lifts are usually enough to make rapid progress in some muscles, slower progress in others. So if you decide not to isolate all of your muscles, that’s totally fine. Most of your muscles will still grow.

Just keep in mind that some muscles may only grow at half speed until you decide to train them directly. Others, such as your neck muscles, probably won’t grow at all until you train them directly. So pick which muscles you’re most eager to grow and make sure you’re doing lifts that stimulate them. Maybe you want biceps curls for your biceps but don’t care about doing calf raises for your calves.

For an example of how this all comes together, let’s imagine a guy who wants to build muscle and be strong overall, but with some extra emphasis in his shoulders, arms, upper chest, and neck. In that case, he can build his routine around the big compound lifts, making sure to include some incline pressing, biceps curls, triceps extensions, lateral raises, and neck exercises.

For another example, let’s imagine a woman who wants to build muscle and be strong overall, but with some emphasis on her hips. In that case, the compound lifts will serve her fairly well, since deadlifts are already quite ideal for her hips. But she might want to take that further, adding in some Romanian deadlifts, good mornings, lunges, or hip thrusts.

For more, we’ve written an entire article about exercise selection.

Which Exercises Are Best for Building Muscle?

Once we’ve chosen a mix of general movement patterns that develop all of our muscles, the next thing is to make sure we’re choosing the best variations of those exercises—that we’re doing the movements in a way that stimulates maximal muscle growth.

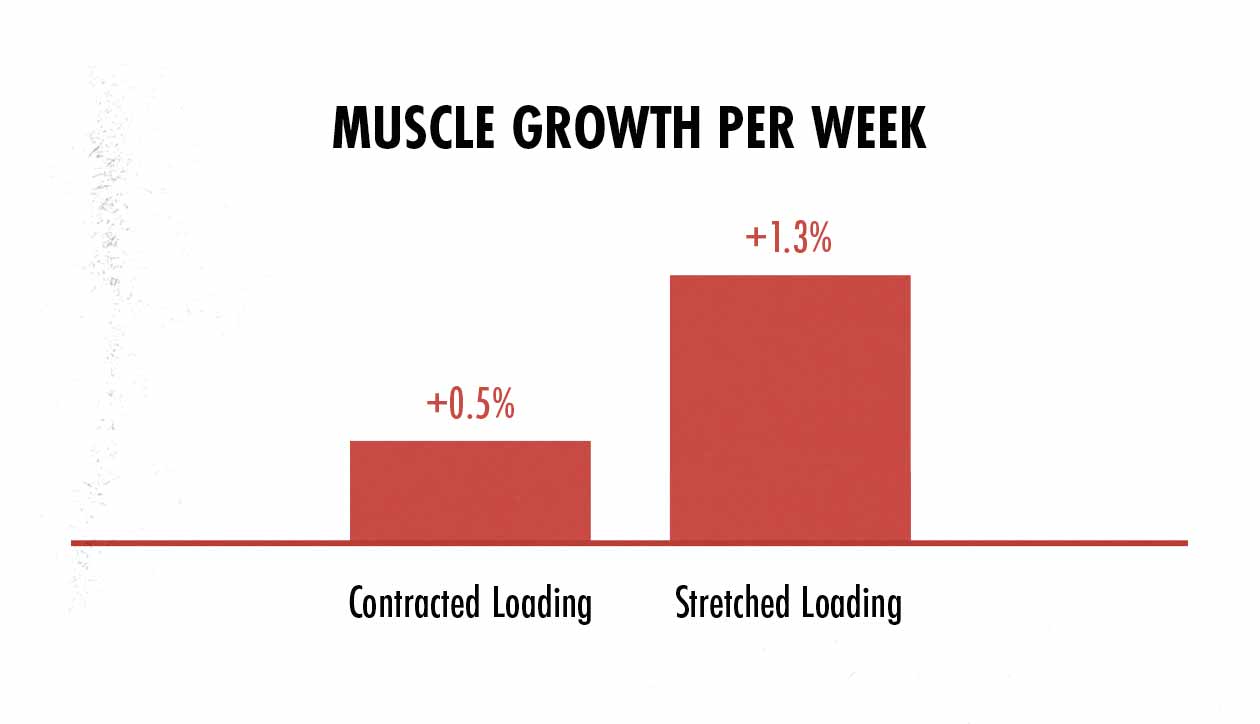

One of the most important parts of stimulating muscle growth is to lift with a deep range of motion. If we look at a recent meta-analysis, we see that by choosing lifts that challenge our muscles in a deeper stretch, we can build muscle over twice as fast. This meta-analysis was looking at isometric lifts, but we see the same thing when comparing exercises that use a full range of motion. For example, this study found that doing leg curls in a seated position (giving the hamstrings a better stretch) yielded twice as much muscle growth as doing them in a lying position (giving the hamstrings a better contraction).

When choosing your exercises, consider lifts that challenge your muscles under a deep stretch:

- Front squats, leg presses, and leg extensions challenge your quads under a deep stretch.

- The bench press, deficit push-up, dip, dumbbell fly, pec deck machine, and chest press machine all challenge your chests under a deep stretch.

- Deadlifts challenge your glutes under a deep stretch.

- Romanian deadlifts and good mornings challenge your hamstrings under a deep stretch.

- Overhead triceps extensions challenge your triceps in a deep stretch.

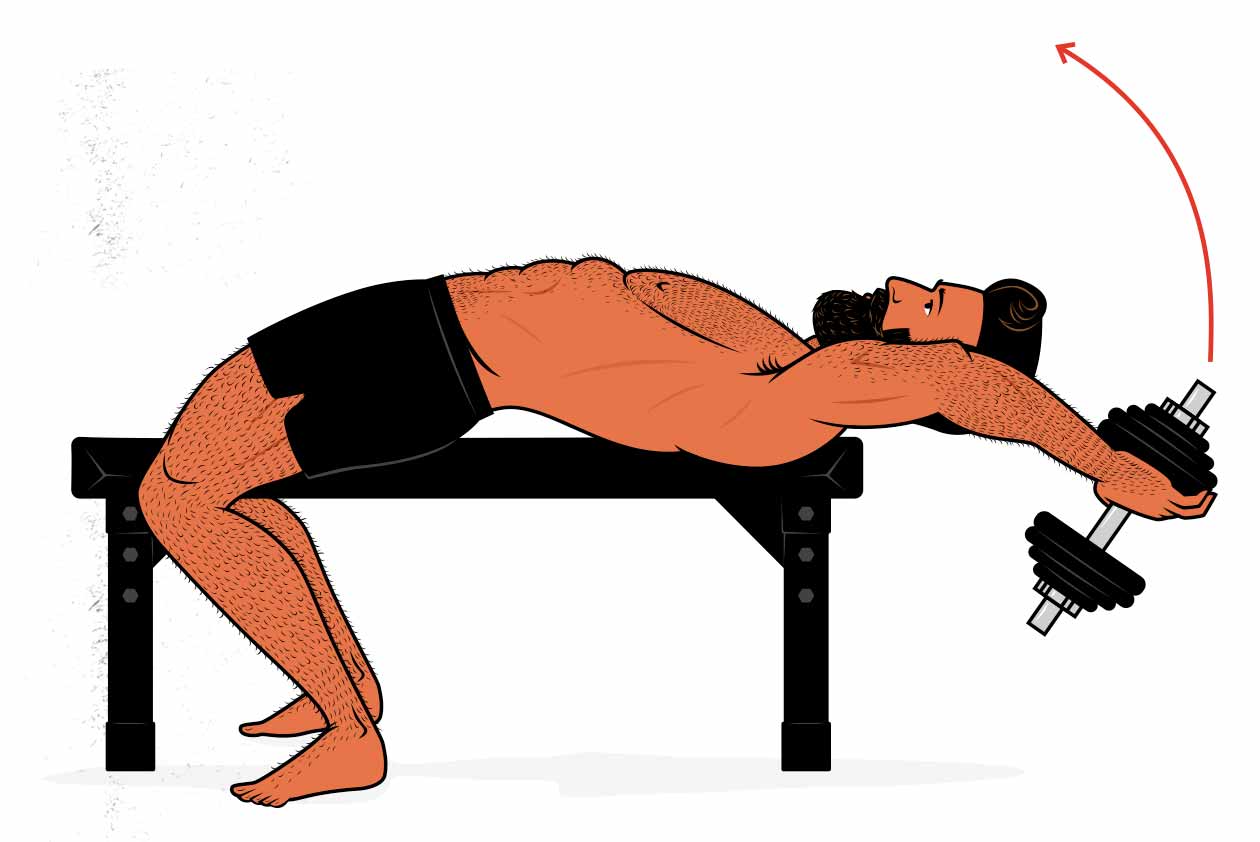

- Lying dumbbell curls challenge your biceps in a deep stretch.

- Pull-ups, pullovers, and pulldowns challenge your lats under a deep stretch.

When doing these lifts, focus on going deep and getting a good stretch at the bottom of the movement. You can lift through a full range of motion, fully contracting your muscles at the top, but it’s the deep part of the range of motion that’s best for stimulating muscle growth, so that’s what you ought to emphasize.

Different Goals Call for Different Exercises

You might notice that this is a little bit different from other styles of training. Unlike in powerlifting, we aren’t doing low-bar back squats to maximize our leverage. Instead, we’re doing front squats to maximize our depth. Unlike in CrossFit, we aren’t doing kipping pull-ups to maximize how many reps we can do. Instead, we’re lifting methodically to work our lats under a deep stretch. And unlike some bodybuilders, we aren’t emphasizing the contraction to get a big pump.

With that said, there are many different ways to lift and many different exercise variations to pick between. The most important part of hypertrophy training is choosing lifts that challenge your muscles and then gradually fighting to lift more weight and more reps over time.

If a lift is aggravating your joints, causing you pain, doesn’t feel good, or you simply don’t like it, that’s okay—use another one. We aren’t powerlifters. There are no mandatory lifts. We can choose the ones that suit us best.

Doing Enough Repetitions Per Set

Hypertrophy training means optimizing your workouts for muscle growth. Lifting heavier to gain strength can be part of that, but so can lifting lighter to improve work capacity. Even better if you combine both styles of training together, stimulating muscle growth both ways.

- Maximal strength: 1–8 reps per set.

- Muscle hypertrophy: 4–40 reps per set.

- Work capacity: 15+ reps per set.

As you can see, there’s quite a lot of overlap there, even when training for a very specific type of adaptation. With hypertrophy training, we can dip down to 6–8 reps per set to develop more maximal strength while still building muscle at full speed. Similarly, we can go up to 15–20 reps to improve our work capacity without sacrificing muscle growth.

Anywhere from 4–40 repetitions can stimulate muscle growth quite well, but it’s quite a bit easier when you lift in the middle of that rep range. This systematic review of 14 studies found that we gain about twice as much muscle from sets of 6–20 reps as we do from sets of 1–5 reps. Low rep sets can work, but you’ll need longer rest periods, and you’ll need more sets.

For example, take a look at this study by Schoenfeld et al:

- The strength training group did 7 sets of 3 repetitions. It took them 70 minutes to finish their workouts, and by the end of the study, they were complaining of sore joints and overall fatigue. Two of the participants dropped out of the study due to injuries.

- The hypertrophy training group did 3 sets of 10 repetitions. It took them 17 minutes to finish their workouts, they were eager to do more lifting, they finished the study feeling fresh, and they gained the same amount of muscle mass.

What’s happening is that when we lift in lower rep ranges, we aren’t able to lift as much weight per set, and so our muscles do less work overall. For example, if we imagine someone who can lift 315 pounds for a single repetition, here’s how much weight they can lift in different rep ranges:

- 1-rep max: 315 pounds for 1 rep = 315 pounds lifted.

- 5-rep max: 275 pounds for 5 reps = 1375 pounds lifted.

- 10-rep max: 235 pounds for 10 reps = 2350 pounds lifted.

So if we lift in lower rep ranges, we lift less weight per set, and so we need to do more sets to make up for that. But lifting in lower rep ranges is hard on our bodies and requires long rest times, making it hard to do enough sets to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth.

On the other hand, as we do more reps per set, we’re doing more total work, which can get quite hard on our cardiovascular systems. If we’re doing a big lift, such as a squat or deadlift, it’s easy to get winded before our muscles give out, turning them into cardio exercises. That’s why we can’t let the reps drift too high, either.

That’s why doing 6–20 repetitions per usually allows us to build muscle faster, more efficiently, and more easily. With the bigger lifts, we can stick to the lower side of that rep range so that our cardiovascular systems don’t hold us back. And with the smaller lifts, we can delve deeper into it. Now, that isn’t to say you should never do sets of 3 or 30 reps, just that you should invest most of your effort, most of the time, into the so-called “hypertrophy rep range” of 6–20 reps per set.

For more, we’ve got a full article on how many reps to do.

Doing Enough Challenging Sets

Most research shows that doing somewhere between 3–8 sets per muscle per workout is enough to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth. If you choose good exercises, lift through a deep range of motion, and strive to outlift yourself, each set can be quite powerful. You might be able to maximize your rat of muscle growth with as few as 4 hard sets per muscle per workout.

The trick is to choose exercises that truly challenge your muscles. As we covered above, doing 4 sets of bench press might be enough to stimulate a maximal amount of hypertrophy in your chest but not your triceps. So that might mean doing 4 sets of the bench press, then 2 sets of triceps extensions.

For more, we’ve got a full article about how many sets to do.

Training Often Enough

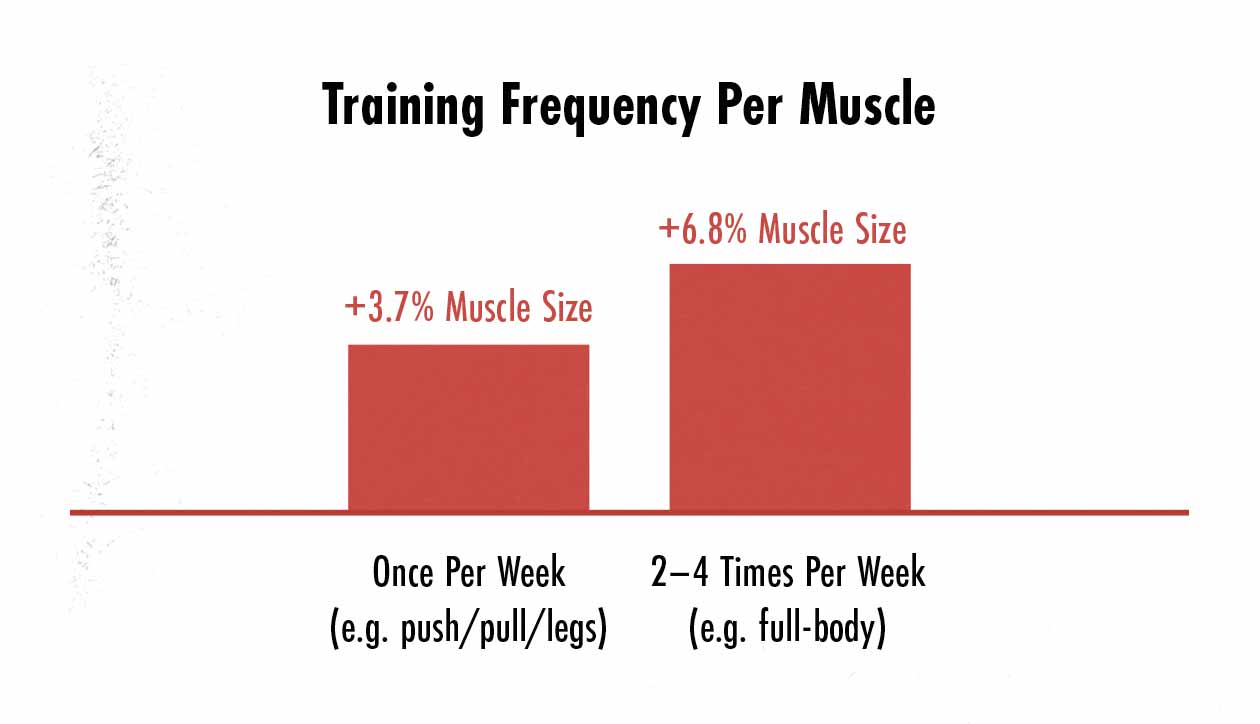

A vigorous workout can stimulate 2–4 days of muscle growth (study). That means you can keep your muscles growing all week long by training them every 2–4 days.

In this meta-analysis, training each muscle twice per week resulted in 48% more muscle growth than training them just once per week. They also looked at people who trained their muscles 3–4 times per week. They grew equally as fast as the guys training their muscles twice per week. That gives you options:

- 3-day full-body routine: This is the best workout routine for beginners. It’s just enough to keep your muscles growing at full speed all week long. You also get more practice with the best exercises, more rest days, and a gentler learning curve. (Here’s our 3-day program.)

- 4-day split routine: This workout routine tends to be slightly better for intermediate lifters. It spreads the workload out over more training days, each muscle gets slightly more time to recover, and you free up more room for smaller exercises. This is the routine Marco was using with professional and Olympic athletes. (Here’s our 4-day program.)

- 5-day split routine: This workout routine can be a good option for intermediate and advanced lifters. The workouts can be shorter and easier, or they can allow you to squeeze even more sets and exercises into the week, allowing you to focus on bulking up more muscles at once. (Here’s our 5-day program.)

All of these workout routines can work equally well. Training more often doesn’t always produce better results. It can, but it depends on how big and strong you are, how robust your joints and tendons are, and how fit you are. Most beginners can get better results by training 3 days per week. Many intermediates do better training 4–5 days per week.

For more, we have a full article on hypertrophy training frequency.

Training Hard Enough

You need to challenge your muscles with every set. Your muscles are already strong enough for easy workouts. There’s no need to adapt to what doesn’t stress you. Challenging training is what tells your muscles they need to grow bigger.

With that said, we’ve already listed progressive overload as one of the most important principles of hypertrophy training. If you’re always trying to lift more than last time, your workouts will always be challenging enough.

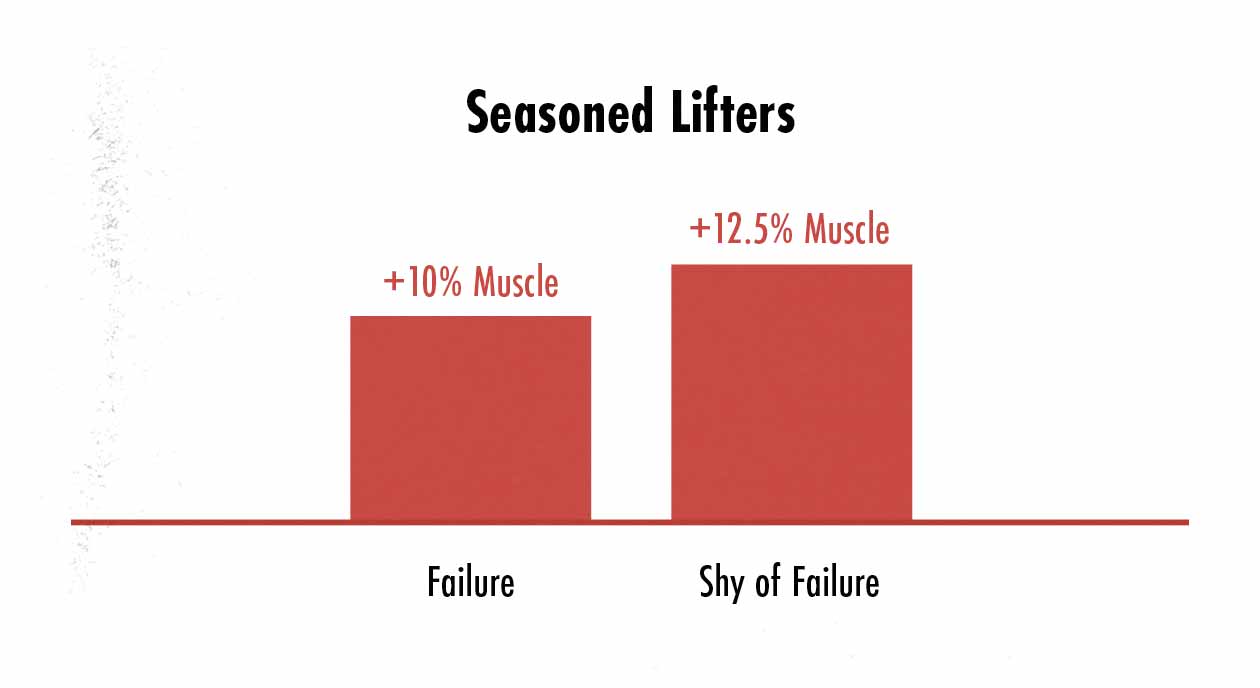

If we look at the research, though, we can get more precise. Ideally, we want to be lifting close but not all the way to total muscular failure, finishing most of our sets with something like 0–3 reps in reserve (study, study, study, study, study).

For more, we have a full article on how close to failure to lift.

Getting Enough Rest Between Sets

To stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth with every set, you need to recover most of your strength between sets. That usually means resting 2–5 minutes between each set. This is how most modern evidence-based bodybuilders train. It’s also how most powerlifters train.

However, if you use shorter rest periods, you can make up for it by doing more total sets. And because you’re spending less time resting, you may actually wind up stimulating slightly more muscle growth in less time. This is how most classic bodybuilders train. It’s also how most athletes train.

As you get stronger, you’ll need to rest longer. Your cardiorespiratory system replenishes the fuel in your muscles while you rest. That’s why you breathe so heavily. You’re turning that oxygen into fuel. Bigger muscles need more fuel, demanding longer rest times.

As you get fitter, you can use shorter rest times. The fitter you are, the faster you can refuel your muscles. You won’t need to rest as long between sets.

Fit beginners can often get away with resting for 30–90 seconds, whereas many powerlifters need close to 10 minutes between sets.

For more, we have a full article on how long to rest between sets.

Making Your Workouts More Efficient

When you rest longer, you gain more strength and need fewer sets, but you waste time resting. With short rest times, you gain more fitness and waste less time, but you need more sets.

Fortunately, you can get the best of both worlds:

- Supersets: this is when you do two exercises together as a pair. For example, while taking a 5-minute rest between sets of the bench press, you sneak in a set of barbell rows. Your chest muscles still get plenty of time to recover between sets, but you’re training your back muscles while you wait. This is great for gaining strength, great for building muscle, and allows you to cut the length of your workouts in half.

- Drop sets: this is when you strip weight off the bar instead of resting. For example, going go from curling 100 pounds to immediately curling 70 pounds, then 50 pounds. The rest times are minimal, but you’re still getting quite a few reps per set. Because you’re lifting less weight, drop sets aren’t as good for gaining strength.

Summary

Hypertrophy training is a style of resistance training that’s designed to stimulate muscle growth. To do that, we train to maximize the strength and work capacity of our muscles. That allows us to build muscle faster, build more balanced physiques, and develop more versatile strength.

Here’s how to train for maximal muscle growth:

- Challenge the strength of your muscles: the most important thing is to choose a style of training that allows you to challenge the strength of your muscles. If you’re limited by your balance, your coordination, or your cardiovascular system, that means you aren’t being limited by your muscles, and so they might not have any impetus to grow bigger and stronger.

- Always strive to outlift yourself: progress won’t be linear, especially as you get more advanced, but the focus of hypertrophy training should always be to get stronger. Focus on adding weight to the bar over time or on eking out extra reps.

- Choose good exercises: we want to build our routines on a foundation of compound lifts, such as the front squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press, and chin-up. After that, we can add in smaller lifts to work the muscles that aren’t being fully stimulated, such as our biceps, triceps, neck muscles, and so on.

- Do enough reps per set: anywhere from 4–40 repetitions per set will build muscle fairly well, but we tend to gain more muscle more easily when lifting in the 6–20 rep range. Usually, the big compound lifts are done for lower reps, the lighter isolation lifts for higher reps.

- Do enough sets per week: most research shows that doing somewhere between 3–12 sets per muscle per workout is ideal for building muscle. If you choose good exercises, train in the hypertrophy rep range, and you lift hard, 4 sets per muscle may very well be enough, and makes for a good place to start.

- Train often enough: to maximize our rate of muscle growth, we want to train our muscles 2–4 times per week. That could be 3 full-body workouts or a 4–5 day workout split.

- Rest long enough between sets: we usually need to rest somewhere between 2–5 minutes between sets, allowing us to keep our performance high from set to set. To speed up your workouts, though, feel free to use supersets (and the occasional drop set).

- Train hard enough: taking each set close to failure is needed to stimulate muscle growth. For the best results, that usually means stopping 0–3 reps shy of failure (without actually failing a rep). But if you’re always trying to lift more than last time, that means you’ll always be testing your limits. This one usually take care of itself.

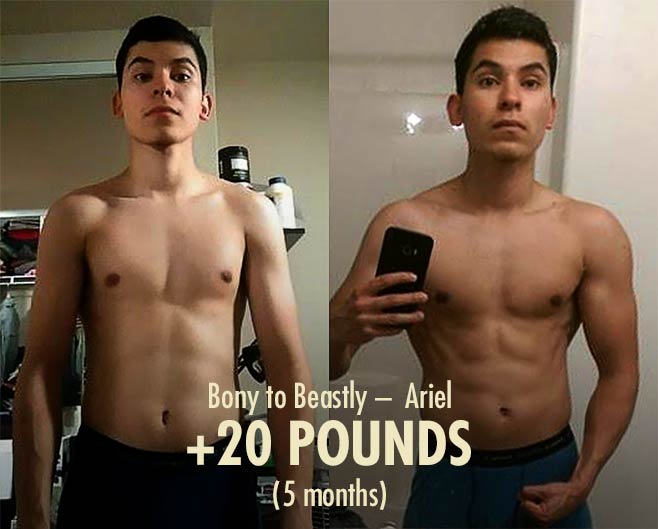

If you haven’t gained your first 20–30 pounds of muscle yet, check out our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. If you’re an intermediate lifter trying to gain more muscle, I recommend our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program.

Hi Shane, happy new year! This is a very comprehensive theoretical (and practical) model for building muscle. Combined with the other in-depth articles makes this website’s content better than most paid materials out there. Said so, I have a question that popped into my mind today after I was grinding the last rep of Press in the infinity set. Why so many advise “stop grinding reps” in order to get out of a plateau?

Seems another generic tip, and would be great to know whether you agree with it and to elaborate on it using your evidence-based style: showing the bigger picture while revealing the nuances within.

(I read also the article about exertion and getting close to failure.)

Hey Thomas, thank you! And Happy New Year to you, too 🙂

A lot of intermediate lifters run into plateaus because they stop lifting hard enough to stimulate more muscle growth. They start leaving too many reps in the tank, they fail to truly challenge their muscles, and so they stop making progress. Among everyday folk, that’s a problem we see all the time.

On the other hand, there’s quite a lot of evidence showing that we can build muscle faster by not taking all of our sets to failure. Not that lifting to failure now and then is bad—and I think it’s often wise—but that we shouldn’t take EVERY set to TOTAL muscular failure. So for the diehard lifters who give every set everything they have—which includes a lot of people making fitness content—there’s often value in holding back a bit. I’m guessing that’s where the advice to stop grinding reps comes from.

It also really depends on the lift. Sometimes grinding through a rep means that form degrades. In a sense, it’s going past technical failure. For other lifts, grinding a rep is just how it goes when you get close to failure. For my front squats and overhead presses, I can often grind for 2–4 reps before approaching failure. So if I stopped my sets before the grind, I wouldn’t be lifting close enough to failure to stimulate a robust amount of muscle growth.

I think it’s important to learn how to grind, learn how many extra reps you can grind through. Not that every set needs to be all-out, but that it’s important to practice doing it so that you know your limits. Maybe stopping a rep shy of failure means doing two brutal, grinding reps. If you never test it, you’ll never know.

But if you take every set to failure, yeah, maybe not ideal. That’s why with Outlift, that last infinity set is aiming for 2 more reps than your main working sets (before increasing the load). That means that most of our work is done well shy of failure. It forces those who never lift close to failure to work harder. And it forces people who always lift to failure to save it for their final sets.

Hi Shane, I have a workout full body consist of 3 sets of 6-8 reps for pushups, pulllups squats, and 3 sets of 10-12 reps on lateral raises, all of these performed 3 times a week, then only if I hit the top range for a certain exercise for all sets, I will increase the weight, for example:

Monday – Pushups

Set 1: 10lbs x 8 reps

Set 2: 10lbs x 8 reps

Set 3: 10 lbs x 7 reps

Wednesday – Pushups

Set 1: 10lbs x 8 reps

Set 2: 10lbs x 8 reps

Set 3: 10 lbs x 8 reps

Friday – Pushups

Set 1: 15lbs x 8 reps

Set 2: 15lbs x 7 reps

Set 3: 15 lbs x 6 reps

What are your thoughts about my workout? Should I add 1 core work? or should I change it from 3 sets to 4 sets per workout, having a total of 12 sets per muscle group per week instead of 9

That sounds great, Rader!

You can add core work if you want. You don’t have to. I don’t do any dedicated core work, but if you want bigger abs and obliques, it will absolutely help.

The movement that’s missing from your routine is the deadlift. Something like a Romanian deadlift would solve that. Could alternate between deadlifts and squats so it doesn’t become too much. That way you’re training both your quads and hamstrings with the same fervour, and your spinal erectors, traps, and other back muscles will get more work.

I’d stay with 3 sets per exercise for now. If you start to struggle with recovery, take an easy week where you do only 2 sets. If you start finding it hard to make progress, add a fourth set.

Hi Shane

Thank you for taking the time to write this. I found your article very informative and an excellent summary of how to approach muscle hypertrophy training; akin to a lengthy book on the subject without having to dedicate many hours reading it!

Taking nothing away from what you have written so well, I would be interested to know your thoughts on emphasising the negative portion of a rep, as this was not mentioned in your article?

Former Mr Olympia Dorian Yates (who I respect enormously) places a lot of emphasis on the negative portion of the rep in his training – and also advocates training to absolute failure on the last set of each exercise, using partial reps as well when the muscle is fully exhausted. This is covered well in his ‘Blood and Guts’ series which I think is still available on YouTube. Not a plug for this but I thought I’d mention it.

Best, Alex

Hey Alex, thank you so much!

Dorian Yates is somewhat of a contrarian. His High-Intensity Training (HIT) doesn’t really line up with the hypertrophy research. It may very well have been ideal for him at that point in his life, but it doesn’t seem ideal for building muscle for most people. HIT’s really interesting from an efficiency standpoint, though. Doing one extremely challenging set might be a good way to get decent results in far less time. I’ll often do a single hard set of an exercise, though not usually when I’m doing a dedicated bulking phase. It’s more something I’ll do when I’m just trying to maintain my strength on that lift.

We’ve got an article on lifting tempo that you might like. Long story short, it makes sense to decelerate the weight as you lower it down. Instead of dropping the weight down, keep it slow and under control. There’s no need to emphasize the negative portion of a rep, though. Spending 1–2 seconds lowering it is usually enough. (The main exception is when using very heavy weights. To maintain control, you might need to lower the weight down quite slowly. For instance, it takes me a good few seconds to lower 315 pounds down to my chest when doing a max bench press. That’s rarely an issue when lifting in the hypertrophy rep range, though.)

We’ve got an article on training to failure, too. Most of the time, it’s wiser to stop 0–2 reps shy of failure. So the most intense you’d go is doing the last rep you can do. You wouldn’t actually reach failure on most of your sets. But, yeah, on the last set of an exercise—especially a smaller isolation exercise—it can help to go to failure.

Should you ever go past failure? Maybe! Drop sets can work quite well, and that’s a form of going past failure. They aren’t THAT different from partial reps.

[…] point is, with proper hypertrophy training, a sufficient bulking diet, and a healthy muscle-building lifestyle, we can grow like weeds, […]

Lacks accurate content. Easier to just get the correct information from Jonni Shreve. At least he has the physique as a testament.

I’m not familiar with Jonni Shreve. His content may be great. Getting advice from the people with the best physiques is usually a bad way to do it, though. You’ll be following the advice of the guys with the best genetics taking loads of PEDs. They may also be guys who have been training several hours per day since they were kids.

I think it’s much better to follow the advice of guys who seem sensible, follow the evidence, have a good reputation, and who are able to produce the transformations you’re hoping to achieve. Look at the client results, you know?

Again, though, I don’t know anything about Jonni Shreve. He may have all of that 🙂

Incredibly professional response. Shane, I appreciate your research-based approach and that you religiously cite studies along the way. Also—you do have the physique to back up the advice!

Thank you.

Thank you so much, man!

I like the simplicity of this article. A lot of what you said makes sense. I have a few questions, though.

1) Why do you say the pec fly machine puts a greater stretch on the pecs than the cable crossover? I would think the cable crossover puts a greater stretch on the pecs because it has more freedom of movement and better range of motion: you can go back as far as you want to in the negative portion of the rep.

2) Can you please explain why front squats put a greater stretch on the quads than back squats?

3) I don’t understand why you wouldn’t want to train to failure. For one thing, how can you grow if you keep doing things within your range of ability? Why not reach for that extra one, two, or three reps, and keep going until you can’t anymore? For another thing, how do you know how many reps you have “in the tank”? Every time I’ve thought about stopping when I felt I had x amount of reps in the tank on an exercise, when I actually push until I can’t anymore I actually do more than I thought I had left in me. That’s happened many times while working out, and I’ve actually been able to do more and more reps on many exercises workout to workout on a lot of my exercises.

Thank you, Ethan!

1. Cable crossovers aren’t bad, they just probably aren’t the very best. It’s possible to set up the cable fly so that it’s hardest at the very bottom and easiest at the top, but most people don’t do it that way, and it wouldn’t be as stable as the other setups. Plus, at that point, since you’re replicating the strength curve of free weights, it’d be easier to just use free weights. Using a chest fly machine might be even easier still.

2. Front squats make it easier to squat deeper. Shifting the weight forward keeps the torso more upright, freeing up more space at the hips, and thus allowing people to drop lower. Some people can go all the way down (hamstrings pressed into calves) with back squats, though. It depends on how you’re built. If you can squat all the way down with the barbell on your back, you’d get that same advantage from back squats.

3. Training to failure stimulates more muscle growth per set, but it hinders performance on subsequent sets, resulting in less work overall. It can also make your workouts harder to recover from, reducing the amount of volume you can manage. It’s usually better to save failure for the final sets of an exercise (assuming it’s safe to take that exercise to failure), for smaller isolation lifts, or for exercises where failure is just a reduction in the range of motion (like lateral raises, rows, biceps curls, pull-ups, pulldowns, and so on).

You’re right. To know how far away from failure you are, you have to experiment with going to failure. That’s extremely important, especially as a beginner. That’s how you develop an intuitive feel for it. And, of course, you can continue taking some sets to failure.

We aren’t against training to failure. Our main Outlift program has you take all your final sets to failure.

Oh, okay. Thanks for clarifying your reasoning behind all that. Thanks!

What about time under tension, such as a set lasting for 45 seconds? If you vary the tempo based on weight you can hit the 2 reps left in the bank. Referencing the common 12 reps which was intended with a 4 second count, hence hypertrophy range was typically at 12. Say I have no weights and doing push-ups and I can do twelve in 45 sec but can keep going, I know it’s ideal to add a weight vest or something. but what about doing faster tempos so I fatigue near 45 secs. maybe the total work would be close to the same as weighted vs unweighted more reps. Basically trying to get creative with what we have on hand.

I don’t think time under tension is the key variable. Most research shows pretty similar muscle growth with reps lasting anywhere from 2–8 seconds. That means you can lift slowly if you want to, but you wouldn’t need to count time under tension, just how many reps you’re doing. If you’re doing slow reps, you’d gradually add weight or reps, just like if you were doing faster reps.

I think a better default is to lift pretty explosively. You develop more strength and athleticism that way. But lifting slow is similarly good for hypertrophy.

I’d forget about 45 seconds and instead focus on doing more push-ups or harder variations of push-ups. If you can do four sets of 12, 11, 10, 9 push-ups, try to add extra reps to those sets next workout. If you get up to 20 or 30 reps and the sets start hurting like crazy, you could find a harder variation. Raising your feet up, for instance. That would shift more weight onto your hands.

Hey Shane! Sam here. Wanted to get your thoughts on something that I’ve been wondering about for a while.

We all know hypertrophy is king. Push yourself in the gym and give your body the tools it needs to grow, and voila: bigger muscles. I’ve often struggled with hypertrophy, and sometimes find myself needing more time than I feel is necessary to move up the weights in the gym. My question to you is, is there an ‘industry standard’ regarding strength (and therefore mass) gain? I do know that strength and mass gains are fastest as a beginner and slowest when nearing genetic potential, but I remain curious as to what those rates should look like.

Consider this example: say I enter a competition with a friend (Joe). Joe and I have been lifting for a few years, and can both bench 200 for 5 reps at the start of the competition. After 90 days, Joe can bench 250 for 5 reps, but I can only bench 225 for 5 reps. Is Joe’s rate of strength gain abnormally fast? Is mine abnormally slow? What should the rates of strength gain look like for beginner, intermediate, and advanced lifters? 10, 5, and 2% a month respectively? Higher? Lower? I often find myself feeling like I am below ‘industry average’ but maybe I am overestimating how fast people actually gain muscle.

Curious what you think!

The first part of your question is pretty easy to answer. In the strength training world, your level is defined by how quickly you make progress. A beginner is someone who gains strength every week, an intermediate is someone who gains strength every phase (e.g. every month), and an advanced lifter is someone who gains strength every program (e.g. every 6 months).

I’m not sure that helps, though. You’re trying to figure out how quickly you should be making progress, not what level you’re at, right? That question is much harder to answer.

Greg Nuckols write an article about realistic rates of progress, but he only surveyed powerlifters, so it’s very specific to powerlifters. If you already feel behind, reading about naturally strong guys who train exclusively for strength probably won’t help.

I wrote a few somewhat similar articles comparing strength with the amount of time someone’s been lifting:

How Much Should You Be Able to Squat?

How Much Should You Be Able to Bench?

How Much Should You Be Able to Deadlift?

How much Should You Be Able to Overhead Press?

You also need to consider how much you weigh. If you and Joe both have similar frame sizes, weigh the same amount, and eat similar bulking diets during your competition, then the person with better muscle and strength genetics will probably gain more strength.

However, if you’re a tall, lanky 160-pound guy and he’s a short, stocky 200-pound guy, and if neither of you guys are eating in a calorie surplus, then you’d expect him to fare far better. He has a better frame for strength, and he has more meat on his bones that he can turn into muscle, and perhaps more muscle that he can learn how to contract more forcefully. He wins because of structure and building materials. You’d need to make up for that by eating more food, gaining more weight, building more muscle, and choosing lifts that suit your frame better (like the deadlift).

Also, if you notice that Joe is racing ahead of you in the competition, there are things you could do. Eating enough food to build muscle is an obvious one, but you could also increase your training volume (which often helps low-responders), frequency (to give you more practice with the movement patterns), and you could also train more specifically for the bench press (making you better at your competition lift). You could stop doing 10-rep sets of dips, 12-rep sets of flyes, and 15-rep sets lateral raises and instead spend more time doing 4–8 rep sets of pause bench presses, close-grip bench presses, incline bench presses, skull crushers, and so on.

I wouldn’t worry too much about your rate of strength gain. I’d worry more about whether you’re consistently setting new personal records (PRs). If you go from benching 200 to 225 pounds, that’s good. That’s a win. We could try to get you faster progress, but I’m still counting that as a win. Then we’d go at it again, this time hoping for 250, but even 240 would be a win.

What you need to watch out for is setting a PR of 225, then slipping back to 200, and then bulking back up to 225. You’re yo-yoing at that point. We want that PR at the end of every bulk. We want to see that you’re making lifetime progress.

The other good thing is that some people make steady gains for a very long time. Just because you’re gaining slowly doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll cap out sooner. Joe might get stuck at 250 while you slowly work your way to 275.

If you weigh less than the average guy (who weighs 200 pounds), that can limit your strength, but it can also help with bodyweight exercises. So don’t just track your bench press. Also track your push-ups (and chin-ups).

Does that help at all?

Hi Shane,

I’ve been following your programs for about a year and a half. Currently starting a new strength phase of Outlift and making progress, slowly but surely.

I’m expecting this phase will crush me and could use a bit of a reprieve from big lifts afterwards. Every phase in Outlift emphasizes the “Big 5”, albeit in different rep ranges, and I wonder if a more drastic change in routine could be more productive. Do you have an article on how to think about phasing to aid in both recovery and ensuring the kind of diversity that helps with making new adaptations?

I’m (unexcitedly) heading for a cut in January which would line up with Phase 1 of Outlift with an emphasis on work capacity. What if I did a phase of HIIT/plyometrics instead for the first 5-6 weeks of my cut? Or perhaps a work capacity phase that drops the Big 5 and focuses on smaller lifts for high reps? It would be nice to take a break from the Big 5 especially while cutting but I’m worried that I could lose muscle during my cut without the foundation of those big lifts.

Woot! Thank you so much for the support Darren. That really means a lot.

I know exactly what you mean. I like to do alternate between more balanced programs and specialisation programs. I should write an article on that.

Did you get the newsletters with the links for the Black Friday sale? We have some specialization programs there. Guns Blazing would be great for you, I think. Your lower body and spinal erectors would get a break, you’d still hit your upper body reasonably well, and then most of the effort goes to your arms. Training your arms isn’t very fatiguing, so you’ll get great muscle growth while also feeling like you’re taking a break. That isn’t ideal while cutting, though. It works better while eating enough calories to grow.

I wouldn’t do HIIT or plyometrics instead of lifting. I think you’d lose muscle and strength, setting you back. Your fear is justified.

If you want to keep using Outlift, switch to easy mode, choose a routine with more days (4-day or 5-day) and do 2–3 workouts per week. That will drop the volume and frequency down. Your workouts will be shorter and easier. And it should be more than enough to maintain your strength and size while cutting. If you start losing strength, just let me know, and we’ll fix it up 🙂

We have an Inferno program that’s easier to recover from, too. It’s designed to do while cutting.

Thanks, Shane. Amazed by your consistent and thorough replies. Your support keeps me coming back.

Yeah I can’t give my legs a break and do guns blazing, as fun as that sounds. I’m a tennis player who needs leg muscles most of all… and my last dexa scan showed relatively less muscle there than the rest of my body. I don’t have consistent access to a leg press machine but I do have a smith machine that allows me to squat without as much spinal erector work. And I have a leg extension/curl machine. I don’t usually use that thing but maybe now’s a good time for it. I may purchase Inferno to help me during this process.

My pleasure, man! I mean that literally. I enjoy your comments. That’s the fun of writing articles 🙂

Yes, that makes sense. The idea to run through Outlift on the 4-day or 5-day routine but only training 2–3 days per week should still work well. That would keep your legs in the mix while giving you shorter workouts and more recovery.

You can also train your legs with single-leg exercises like step-ups and split squats. Marco is really fond of using those with athletes. And since you’re training one leg at a time, you’re using a fraction of the external load, keeping things pretty easy on your spinal erectors. You’d get potentially greater athletic carryover with less fatigue.

Leg extensions and curls are also great. That’d round our routine routine.

Inferno will be great, too 🙂