The Best Hypertrophy Exercises

Different exercises are designed for different goals. Powerlifters use the squat, bench, and deadlift to demonstrate their maximal strength. Olympic weightlifters use the snatch and clean-and-jerk to demonstrate their explosive power. And bodybuilders use hypertrophy exercises to stimulate muscle growth.

However, hypertrophy training is for more than just bodybuilders. Bigger muscles are stronger muscles, so anyone interested in being bigger, stronger, faster, healthier, or better looking will go through phases of hypertrophy training to gain more muscle mass.

This article is about the best exercises for stimulating muscle growth. It’s up to you what you decide to use those muscles for.

Compound & Isolation Exercises

Imagine trying to fill a bucket with rocks. Some of the rocks are enormous; others are as small as sand. If you start with the smaller rocks, you’d need to carry quite a few rocks to the bucket before making a noticeable impact. Worse, by the time you got to the bigger rocks, they wouldn’t fit properly.

It’s best to start with the biggest rocks. You can fill 80% of the bucket with just a few rocks. Then, when you pour in the sand, it will trickle through those rocks, filling in every nook and cranny.

For example, both the bench press and dumbbell fly work your chest through a similar range of motion with a similar strength curve. As far as your chest is concerned, they’re the same. But the bench press also works our shoulders and triceps. It’s the bigger stone, and once you have it in your bucket, you may not even need the fly.

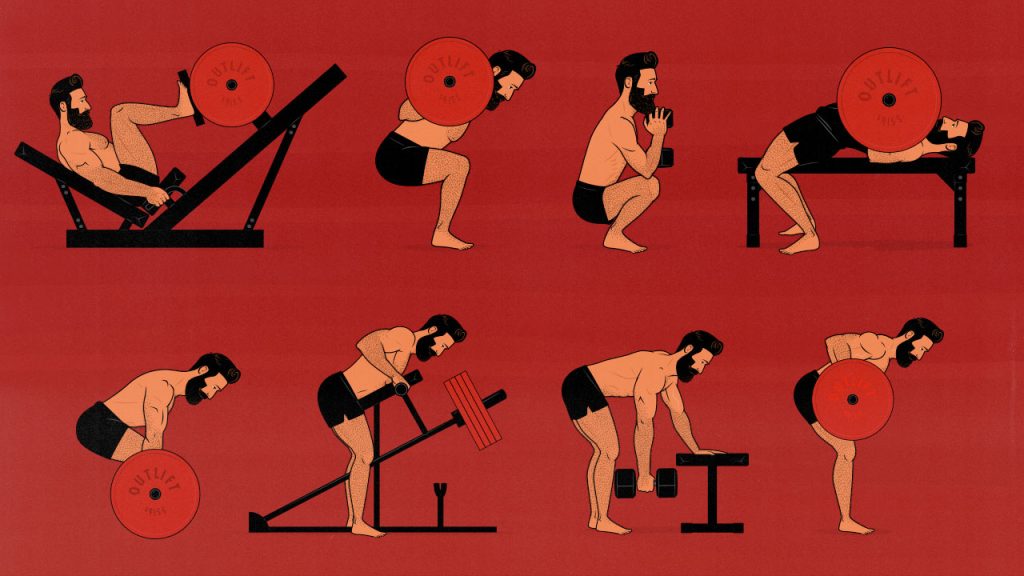

The Best Compound Exercises

Start by choosing your big compound lifts. That’s where you’ll find most of your muscle growth. From there, see which muscles aren’t being stimulated. We can fill in those gaps with smaller isolation lifts.

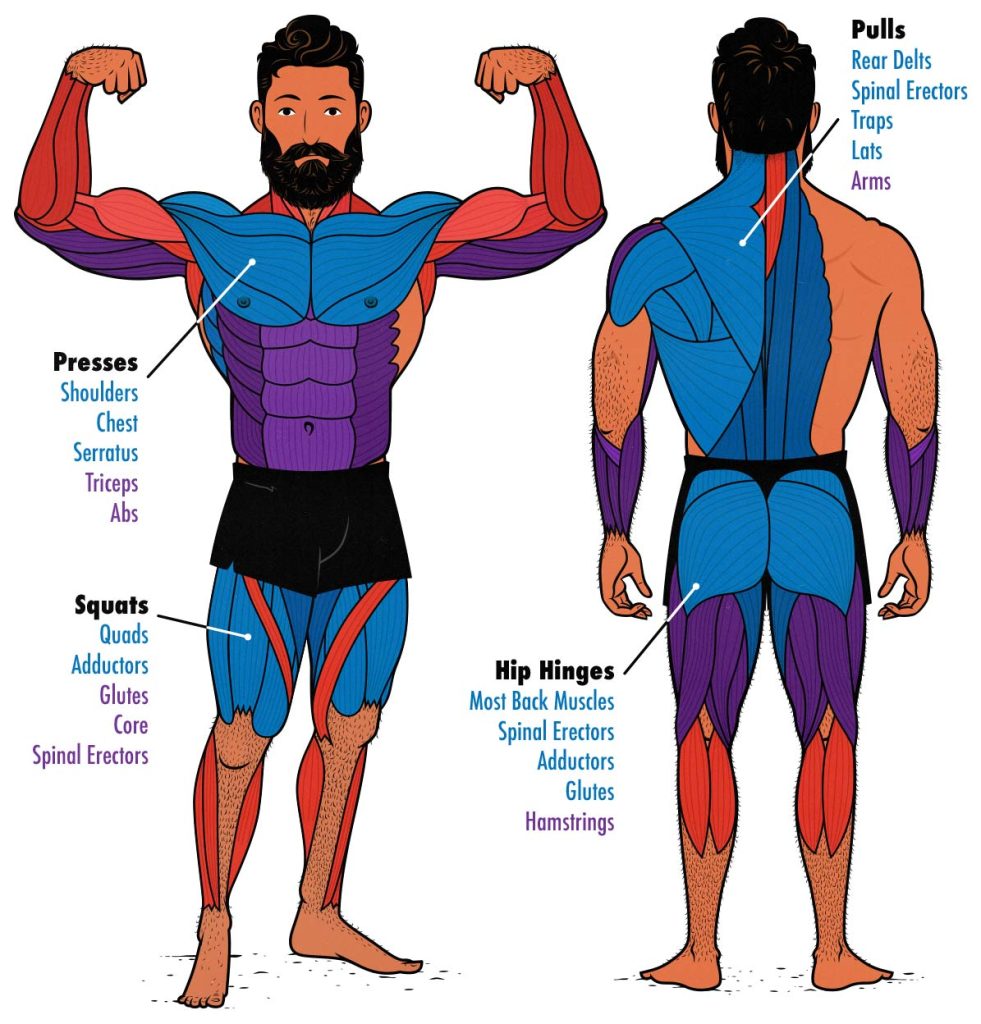

- Squats: Front squats, back squats, and split squats work the quads and glutes—the two biggest muscles in your body. They also stimulate your lower back, adductors, calves, and a slew of smaller muscles.

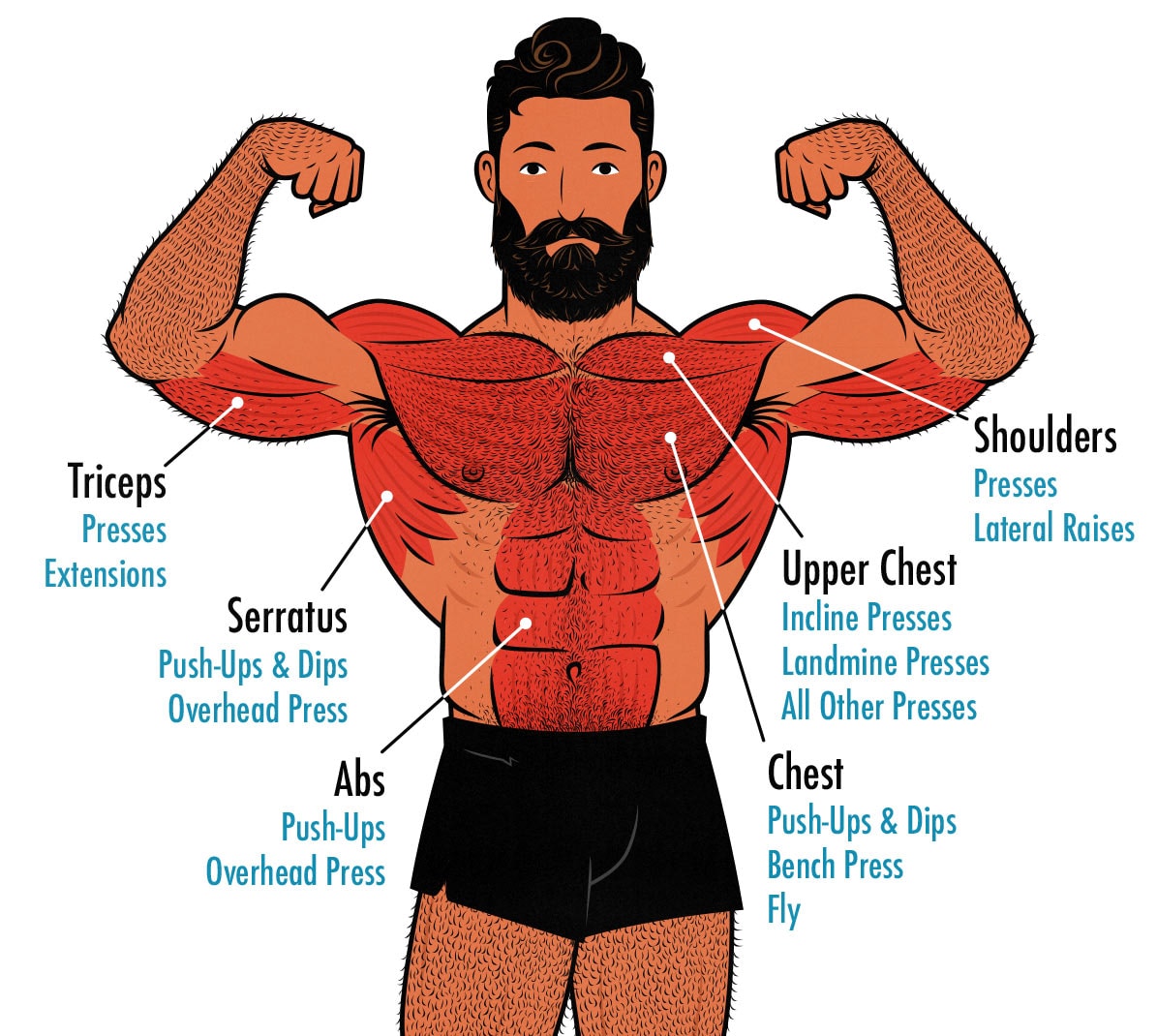

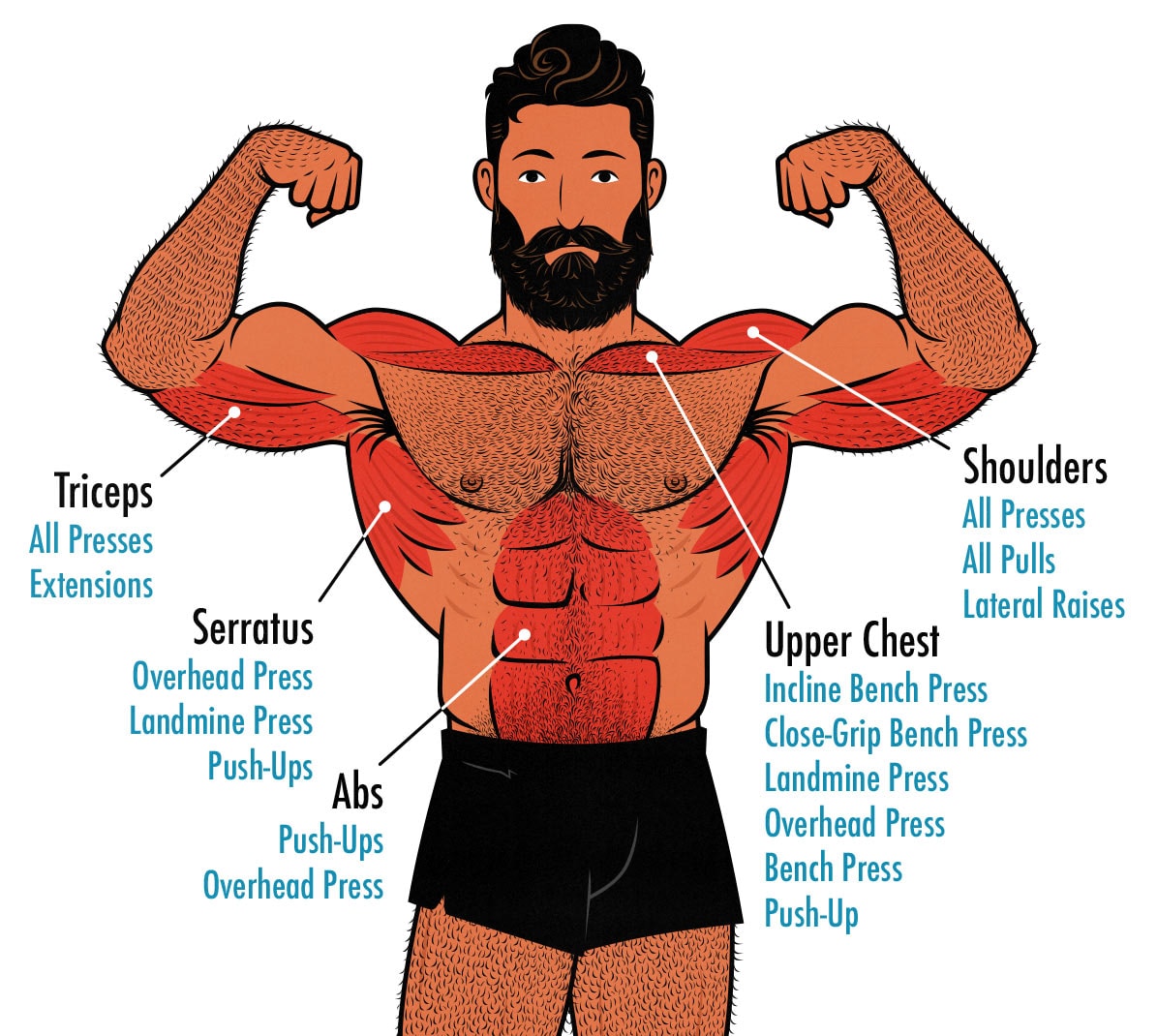

- Horizontal presses: Bench presses, push-ups, and dips work your chest and front delts. They can also work your triceps, serratus anterior, and some of the muscles in your core.

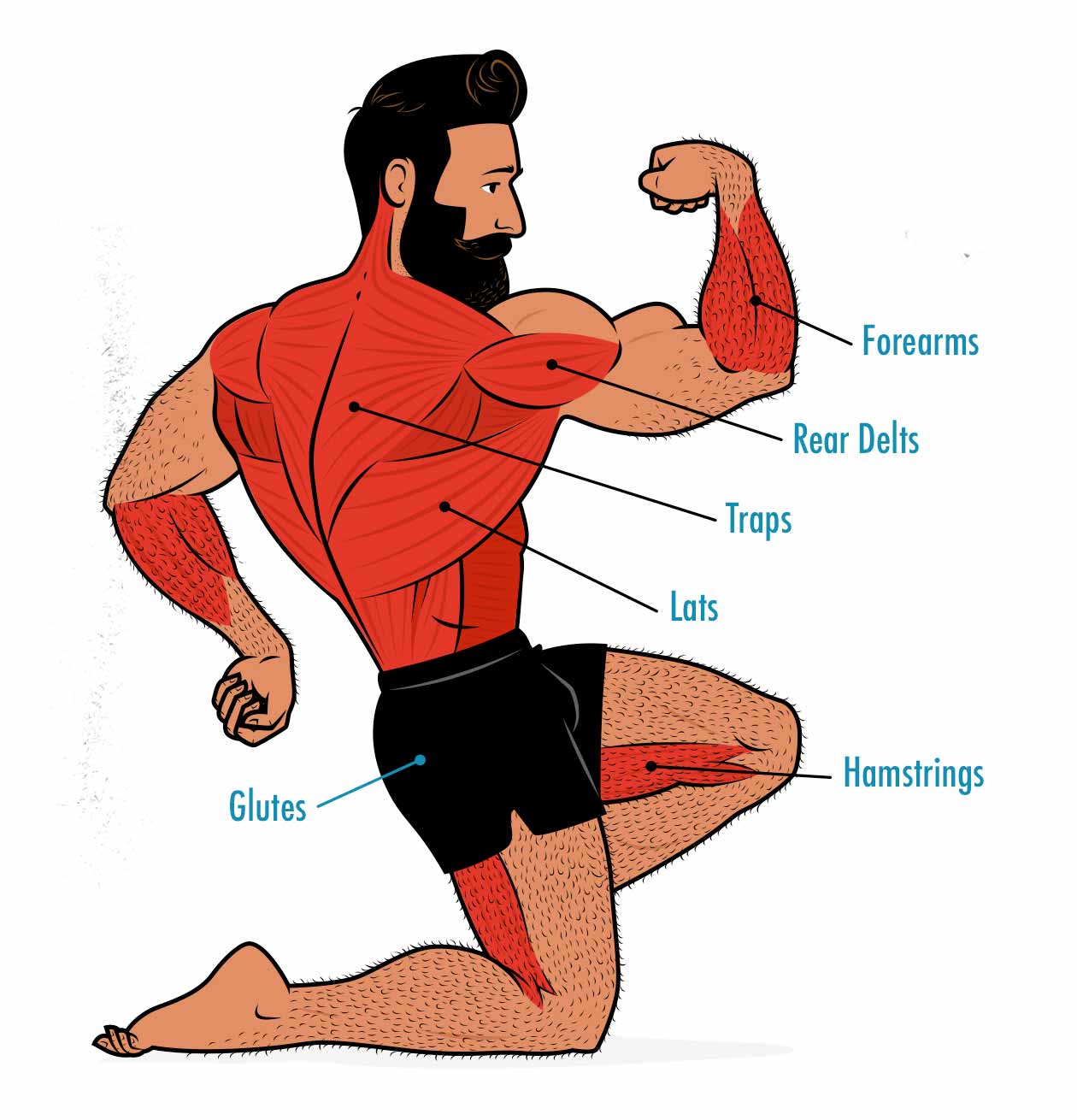

- Hip hinges: Deadlifts, back extensions, and good mornings work your glutes, hamstrings, and spinal erectors. They can also work your upper back and grip.

- Vertical presses: Overhead presses, incline bench presses, and landmine presses work your front delts, side delts, triceps, traps, and serratus anterior.

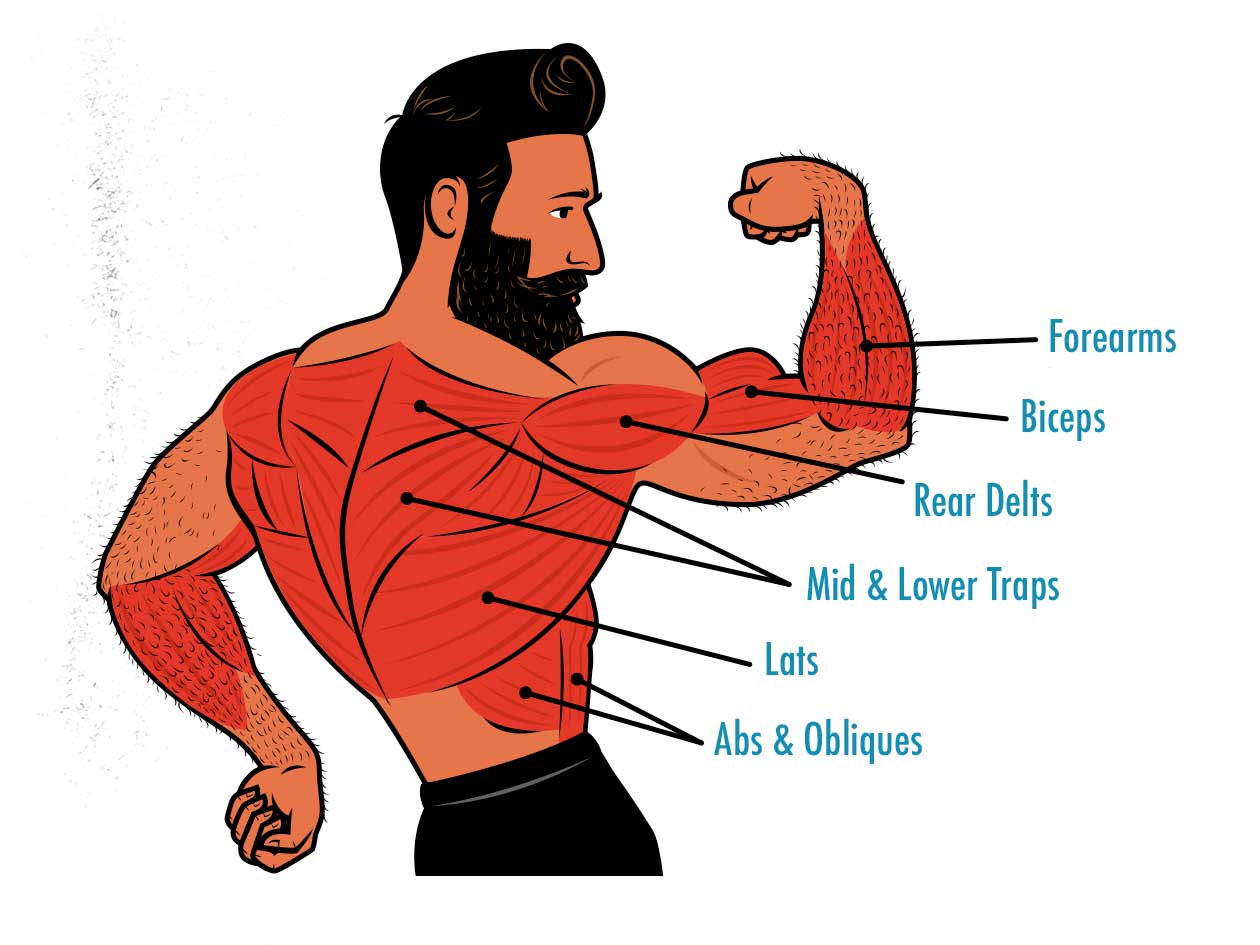

- Pulls: Chin-ups, pull-ups, rows, and pulldowns work your upper back and lats. They can also bulk up your spinal erectors, biceps, forearms, and abs.

These big compound movements can’t bulk up every muscle, but they can get us about 80% of the way there. If you’re curious about which variations are best, we have a deeper article on the Big Five hypertrophy exercises.

The Best Isolation Exercises

Compound exercises can’t train every muscle properly. There are two main reasons for that:

- It’s hard to train muscles that cross two joints with exercises that work two joints. For example, your triceps are famous for extending your elbows, but they also pull your elbows backward. Pressing movements extend your arms while pulling your elbows forward. That makes it hard to build big triceps with pushing movements.

- Some muscles don’t contribute to compound lifts whatsoever. Your neck won’t flex when doing deadlifts or bench presses.

That’s where isolation exercises come in. You don’t need them for every muscle, but if you want a muscle to grow, you do need to make sure it’s being trained properly by at least one exercise (study). In this case, to maximize triceps growth, you need triceps extensions.

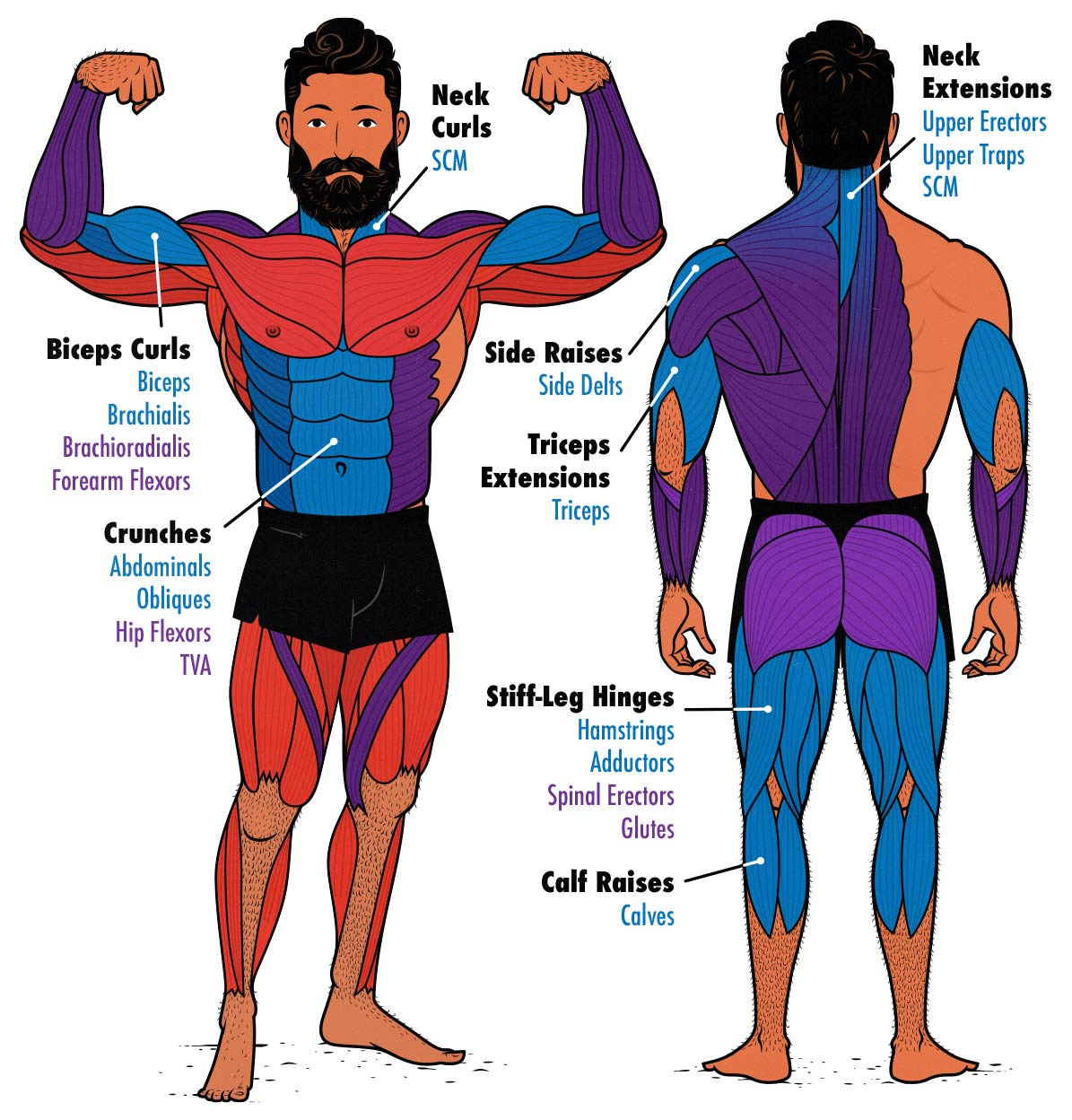

Here are some other isolation exercises you might want to include:

- Triceps extensions work all three heads of your triceps (study).

- Biceps curls work your biceps and forearms (study).

- Leg extensions work all four heads of your quads (study).

- Neck curls work the big muscles in front of your neck.

- Neck extensions work the muscles behind your neck.

- Hamstring curls work your hamstrings.

- Lateral raises work your side delts

- Calf raises work your calves.

- Crunches work your abs.

How to Pick the Best Muscle-Building Exercises

A Deep Range of Motion

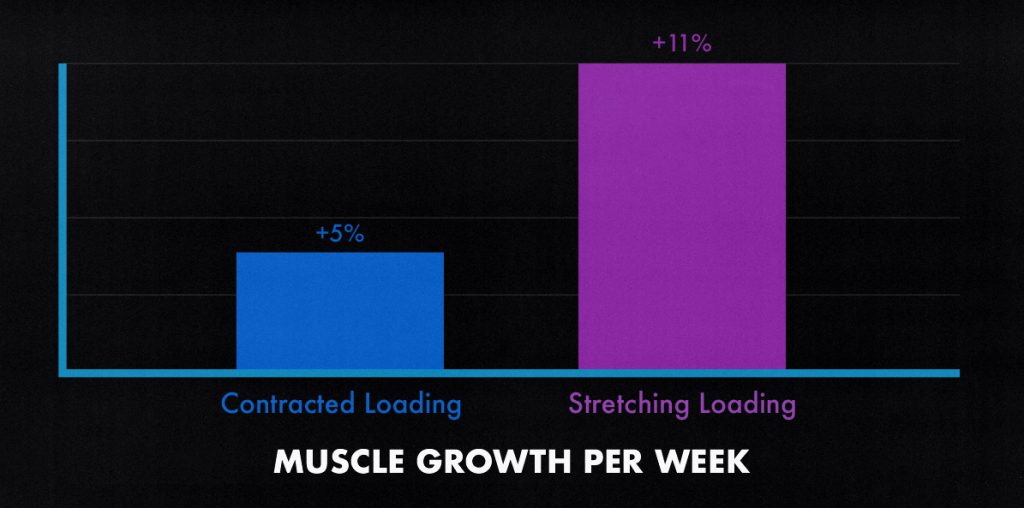

A few years ago, a meta-analysis was published showing that challenging your muscles under a deep stretch stimulates over twice as much muscle growth as challenging them in a contracted position (meta-analysis).

We have a full explanation here, but here’s the simplest way to think about it: when you stretch your muscles, they behave almost like elastics, pulling themselves back to their resting lengths. That tension gets added to the tension you generate by actively contracting those muscles, creating more overall tension and thus stimulating more muscle growth.

Most exercises have us working through a fairly large range of motion. You can challenge your muscles under a deep stretch and with a full contraction. However, different exercises stretch your muscles to different degrees and are harder at different points. When you pick exercises that are harder at longer muscle lengths, you can stimulate quite a bit more muscle growth (study).

Here are some of the best exercises for challenging your muscles under a deep stretch:

- Dips, dumbbell flyes, and deficit push-ups work your chest and front delts under a deep stretch. The bench press can be quite good, too.

- Deep squats, such as goblet squats, front squats, and high-bar squats, challenge your quads under a huge stretch.

- Deadlifts work your traps and glutes under a deep stretch.

- Romanian deadlifts work your hamstrings under a deep stretch.

- Pullovers challenge your lats under a deep stretch. Chin-ups and pull-ups are quite good, too.

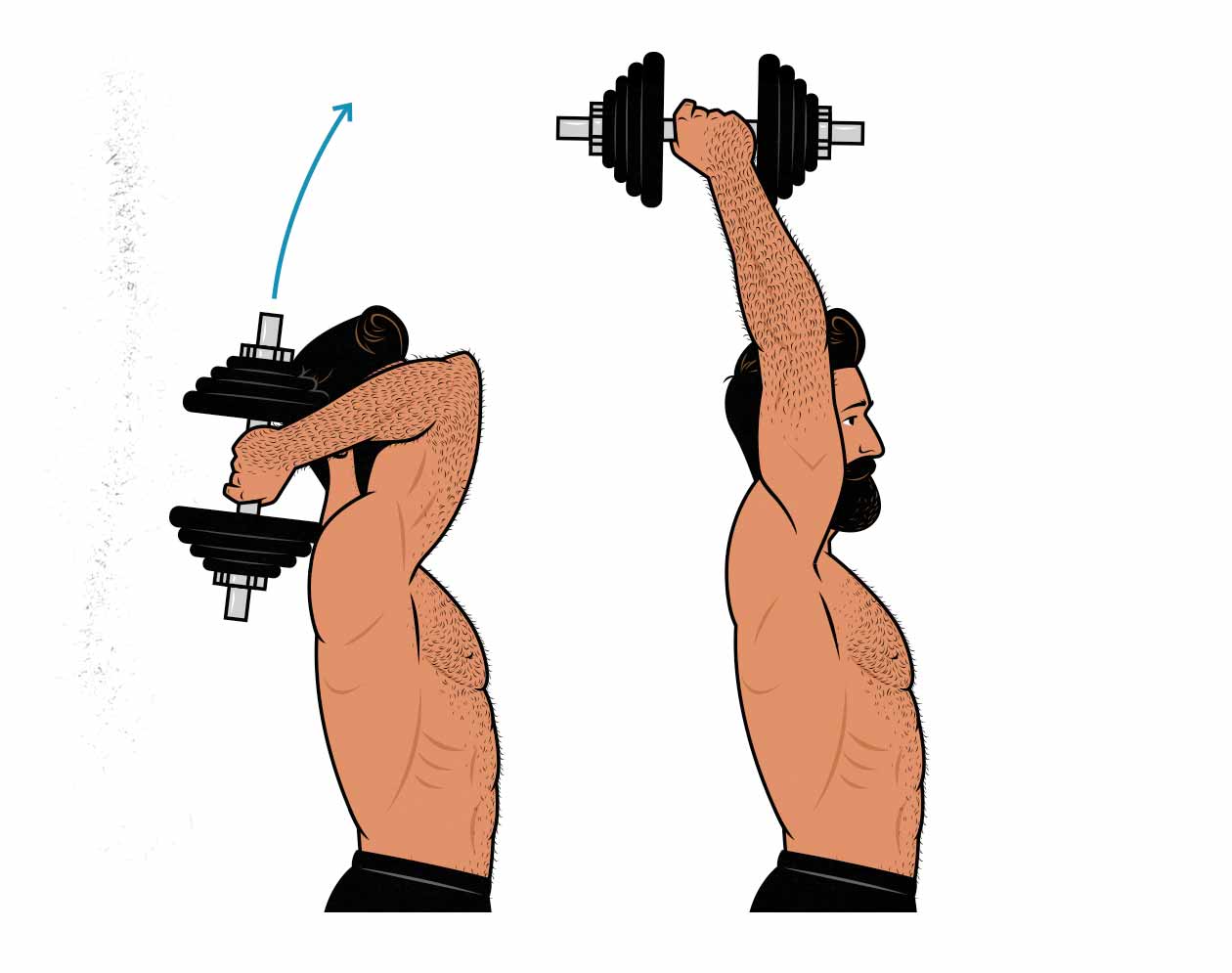

- Overhead triceps extensions are great for your triceps.

- Lying biceps curls are great for your biceps.

Also note that Barbells, dumbbells, bodyweight exercises, cables, and exercise machines tend to be better at challenging your muscles at long muscle lengths than resistance bands.

Stimulus-to-Fatigue Ratio (SFR)

Some exercises allow you to stimulate more muscle growth with less fatigue. You might be able to maximize your rate of muscle growth with heavy strength training, but it would take you three times as long and leave you twice as tired as if you followed a hypertrophy training routine.

There are a few things that tend to improve the stimulus-to-fatigue ratio of your exercises:

- Avoid exercises that hurt your joints. That might mean doing chin-ups on an angled bar, biceps curls with dumbbells, and deadlifts with a trap bar.

- Don’t overdo it with the stress on your spine and spinal erectors. Maybe swap some sets of deadlifts for Romanian deadlifts or some sets of low-bar squats for front squats.

- Some big exercises can be replaced by smaller ones. If you’re too tired for overhead presses, you can do nearly as well with lateral raises.

Just be careful not to overoptimize your routine. If you never challenge your spine, bones, tendons, or work capacity, you won’t grow as dense, tough, strong, or fit.

For more, we have a full article on the stimulus-to-fatigue ratio.

Exercise Variety

Training each muscle with a few different exercises tends to be better for building muscle, gaining strength, and improving your athleticism (study, study, study, study). It also varies the stress on your joints and connective tissues, meaning you’ll be less likely to aggravate your elbows, knees, hips, and shoulders.

Powerlifters need to focus on the squat, bench, and deadlifts. Olympic lifters need their snatch and clean-and-jerk. If you’re training for overall hypertrophy, though, you can use a wider variety of exercises, “building a wider base” for your fortress of muscle. You can do bench presses and dips, chin-ups and rows, overhead presses and lateral raises.

As a beginner, pick a couple of simpler exercises and get good at them. The more often you practice an exercise, the faster you’ll improve at it. You’ll gain more strength and coordination. You’ll be able to stimulate more muscle growth.

As an intermediate lifter, gradually new exercises into your routine, working up to as many as 4 different exercises per muscle per week. Keep those exercises relatively constant for at least a few months. You need time to grow stronger at them. You need to know how much stronger you’re getting.

The Limiting Factor

Once you’ve chosen your exercises, pay attention to which muscles get worked the hardest and which muscles get sore. Different people lift with different muscles. You need to figure out which ones you’re working hard enough.

For example, most people fail the bench press when their chest gives out, especially when they’re benching in a moderate rep range. But it’s not uncommon for your front delts to be the limiting factor. If that happens, you might need extra chest isolation exercises (such as dumbbell flyes) and fewer front delt exercises (such as overhead presses).

Beginner Variations

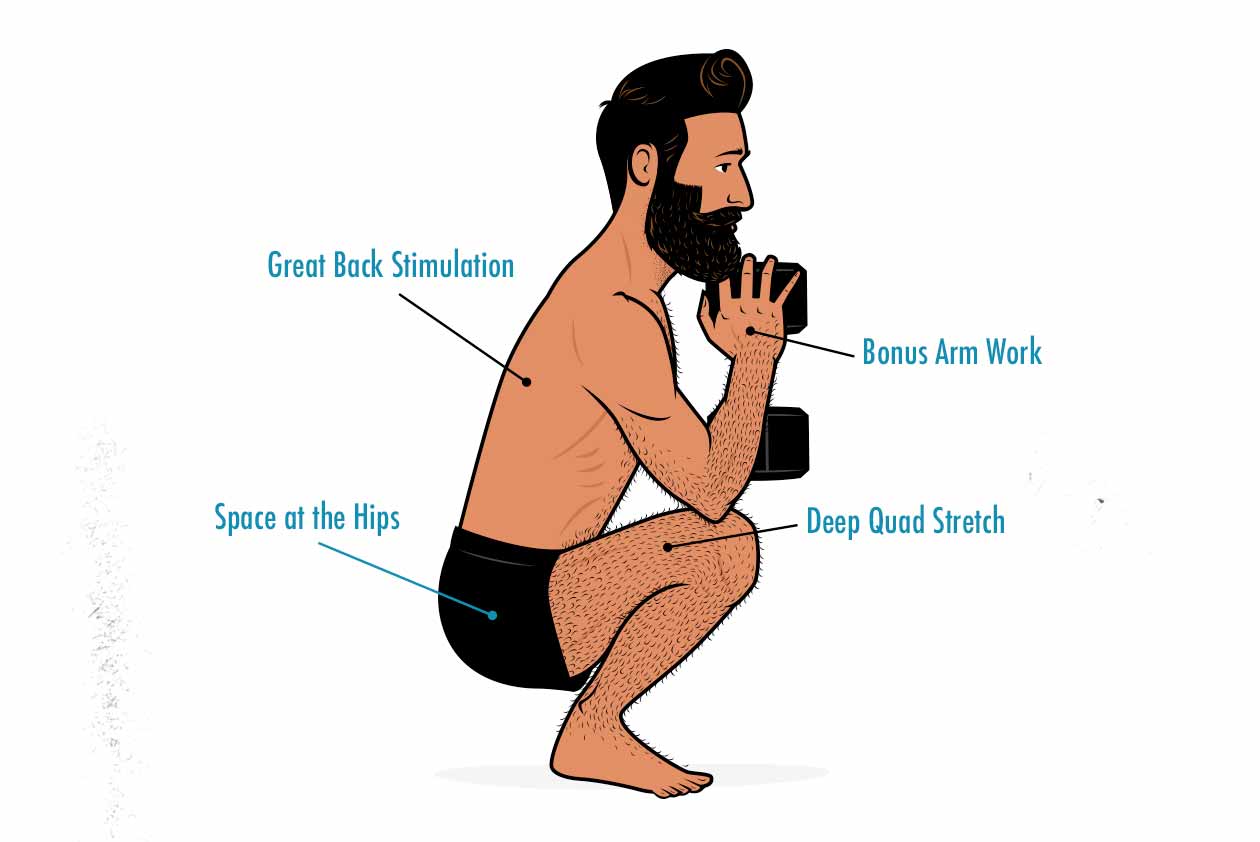

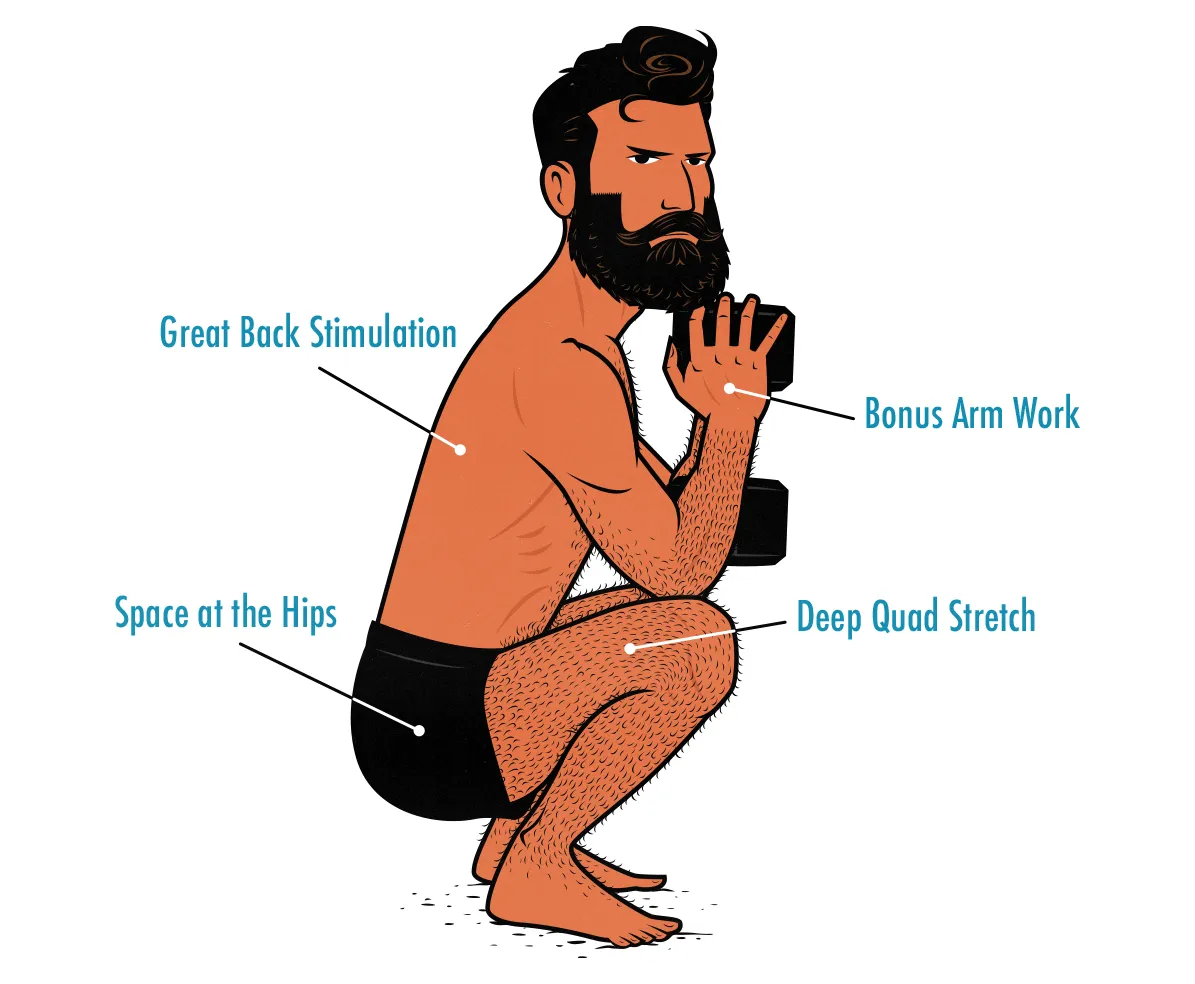

Choose exercises that match your skill level. Front squats are fantastic for building muscle, but most beginners struggle with them. Goblet squats offer almost all the same advantages, but they’re far easier to learn. And once you master them, you’ll have an easier time learning front squats.

If you’re new to lifting weights, here’s how to progress from beginner exercises to more advanced ones:

- Goblet squats => front squats and high-bar squats

- Push-ups => dips and bench presses

- Romanian deadlifts => conventional and sumo deadlifts

- Pulldowns => chin-ups and pull-ups

- Dumbbell rows => barbell rows

That’s the approach we take in our Bony to Beastly Program. We start by teaching the beginner variations (with tutorial videos). Every 5 weeks, we teach you a few new exercises. After 6 months, you’ll have gained 20–30 pounds of muscle, and you’ll be competent at all the big exercises.

Main Lifts, Assistance Lifts & Accessory Lifts

As we explained above, it helps to start with the big compound exercises, then fill in the gaps with smaller exercises. That allows us to sort our exercises like so:

- Main exercises: these are the big compound lifts that form the foundation of your workout routine. The big compound lifts often emphasize the big muscles in your torso—your chests, shoulders, glutes, and back. As a default, we recommend the front squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press, and chin-up.

- Assistance exercises: these are the secondary compound lifts, usually lighter, that complement the main lifts. Think of slightly smaller exercises like leg presses, Romanian deadlifts, seated dumbbell presses, lat pulldowns, and rows. These exercises often emphasize something that the bigger exercises can’t. For example, Romanian deadlifts work your hamstrings much harder than conventional deadlifts.

- Accessory exercises: these are the “isolation” exercises, often working just a single joint. These exercises often focus on your limbs—biceps, triceps, forearms, neck, calves, and so on. Think of exercises like biceps curls, triceps extensions, neck curls, calf raises, and lateral raises. Choose the exercises that work the muscles you’re most eager to grow.

If you’re trying to maximize your rate of muscle growth, choose a main exercise, assistance exercise, and accessory exercise for each movement pattern:

- Squat: front squat + leg press + calf raises.

- Horizontal press: barbell bench press + dips + skull crusher.

- Hip Hinge: conventional deadlift + Romanian deadlift + leg curl.

- Vertical press: incline bench press + dumbbell overhead press + lateral raise.

- Vertical Pull: weighted chin-up + cable row + biceps curl.

Feel free to scale it back. When life gets busy, you can probably maintain your gains with just one big compound lift per movement pattern.

You can also mix and match. If you’re keen on building bigger arms, do extra biceps curls and triceps extensions. If you don’t want bigger calves, skip the calf raises.

Programming the 5 Movement Patterns

The Squat

Squats work your quads and glutes—the two biggest muscles in your body—through a deep range motion with a great strength curve. They’re incredibly powerful.

The Best Main Squat Variations

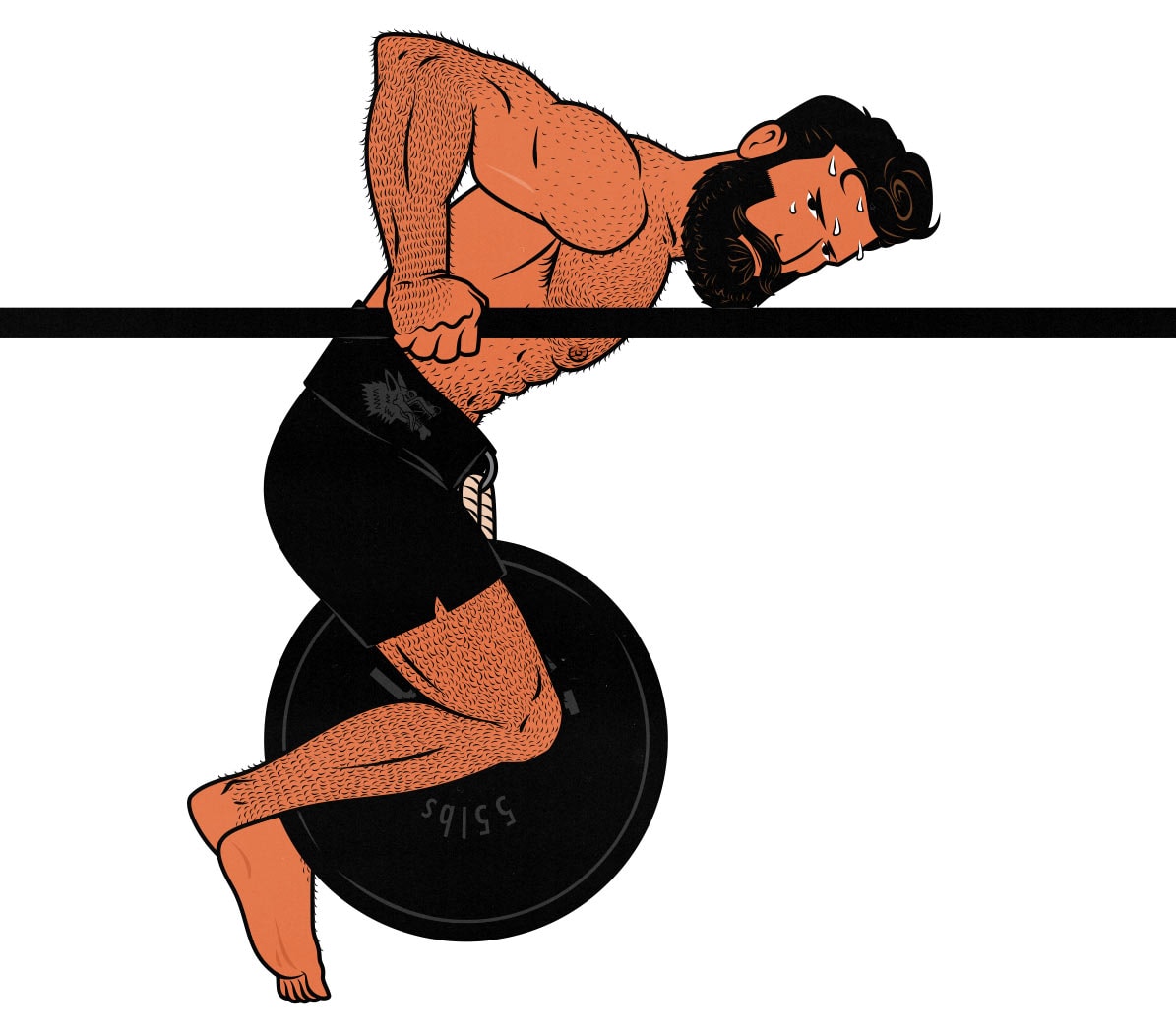

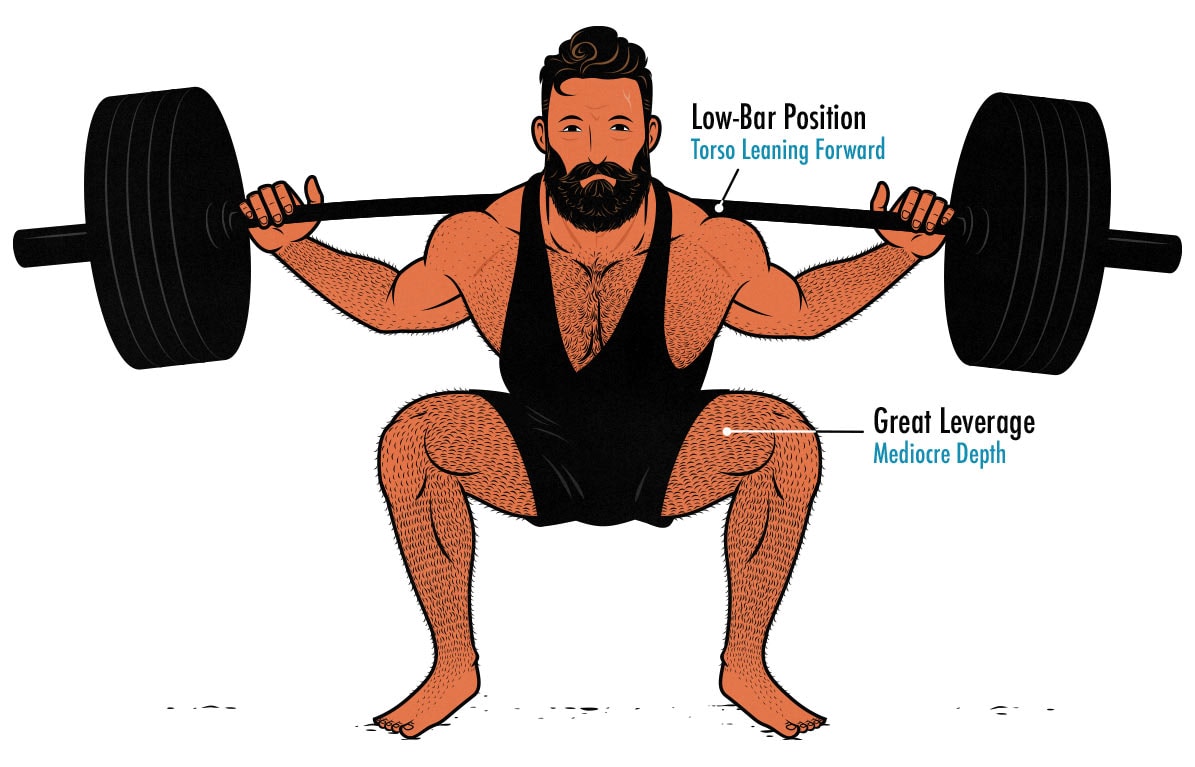

There are a few great squat variations. The back squat is the most popular, with both a low-bar and high-variation. It’s done by holding a barbell on your back, like so:

The low-bar squat is popular in powerlifting because it allows people to lift more weight. The high-bar squat is popular because it allows for a deeper range of motion with a less extreme shoulder position, and is thus a little bit better for general strength training.

For hypertrophy training, though, we’re more interested in stimulating overall muscle growth, and so instead of trying to limit the range of motion, we want to increase it. Plus, if we can choose variations that give us more upper-body growth, that’s a boon. That gives us the goblet squat for beginners, which is done by holding a dumbbell or weight plate in front of you, like so:

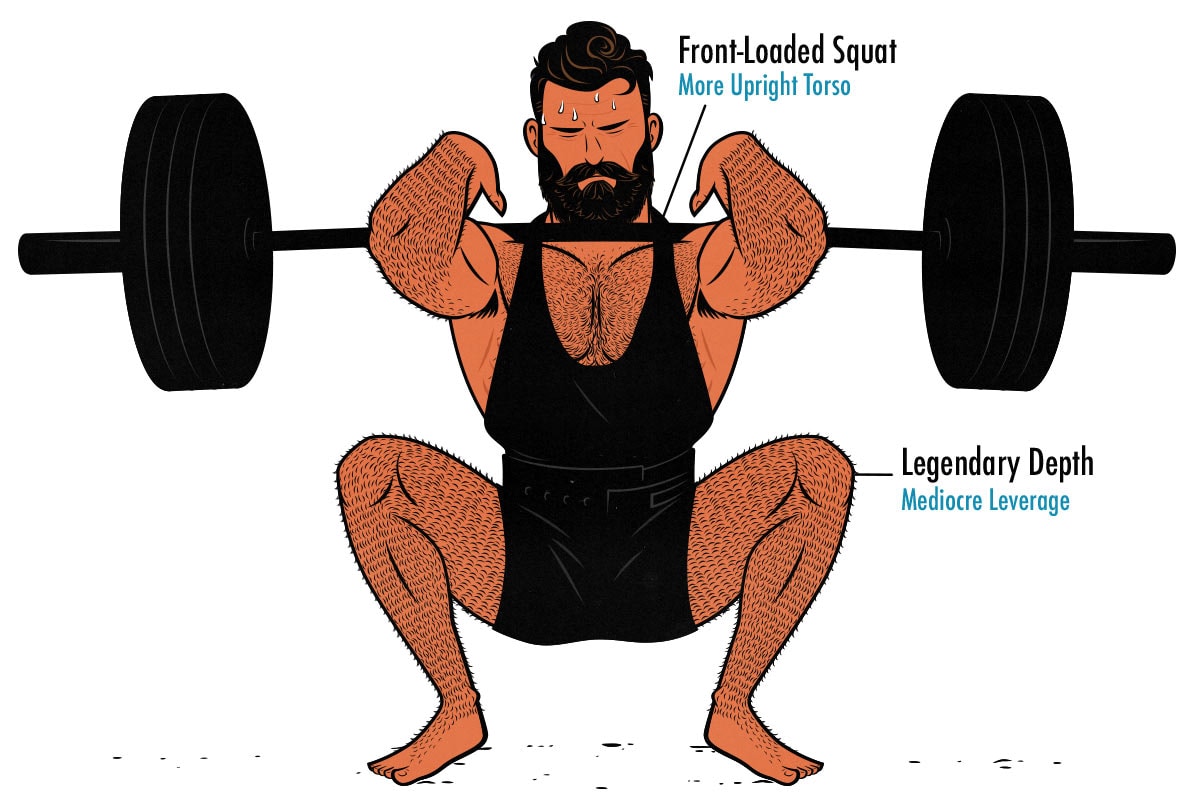

And then once you’ve mastered the movement pattern and/or gotten too strong for the heaviest dumbbell you have access to, you can switch to the front squat. The front squat is done by holding a barbell in front of you, in the crease of your shoulder joint, like so:

The front squat allows the deepest range of motion for our quads, it stimulates growth in our upper backs, it’s one of the safest squat variations, the stimulus-to-fatigue ratio is better than with back squats, it’s often best for our joint health, and it even helps to improve our posture. As a result, it’s a great default squat variation when you’re training for muscle size (bodybuilding, hypertrophy training, general strength training, and so on).

But, as with all the exercises, feel free to pick the squat variation that suits you best. And feel free to alternative between the different variations from phase to phase. You may even wish to include different types of squats in the same training phase, doing back squats one day and front squats another day.

Overall, the best main squat variations are:

- The front squat: ideal for emphasizing the quads and spinal erectors, great for overall hypertrophy, easy to recover from, and carries a low risk of injury. As a result, it’s great for hypertrophy training, and a good default for both bodybuilders and people training for general strength. However, it’s hard and uncomfortable to learn, and if your back isn’t strong, it’s possible that your spinal erectors will be your limiting factor. At that point, your back might get more growth than your quads. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, mind you, it just depends on your goals.

- The high-bar back squat: great for stimulating both the quads and glutes, and is quite a bit easier on the spinal erectors. It’s a good compromise between the low-bar and front squat, and is great for bodybuilders, athletes, and building muscle in general. The potential advantage it has over the front squat is that your back strength won’t be a limiting factor, making it potentially better for the quads. On the other hand, it’s not as good for bulking up the back, making it less of a full-body lift.

- The safety-bar squat: the safety-bar squat is done using a cambered barbell that shifts the weight forward. It doesn’t require any shoulder mobility, making it good for guys with shoulder injuries. Like the high-bar squat, it’s good for emphasizing the quads and glutes without requiring much back strength.

- The low-bar squat: the heaviest squat variation, and also the best for emphasizing both quad and hip growth, making it popular with both powerlifters and women. However, it can put a fair bit of wear and tear on the hip and shoulder joints, it’s often quite fatiguing, and not everyone can do them safely over the longer term.

The Best Squat Assistance Exercises

There are a few different ways to pick assistance lifts for the squat. If you’re doing front squats, you might want a lighter variation that still allows you to work your quads and upper back. For that, the Zercher squat is fantastic. And as a pleasant bonus, the Zercher squat works the hips and traps quite well, making it a great assistance lift for the deadlift, too.

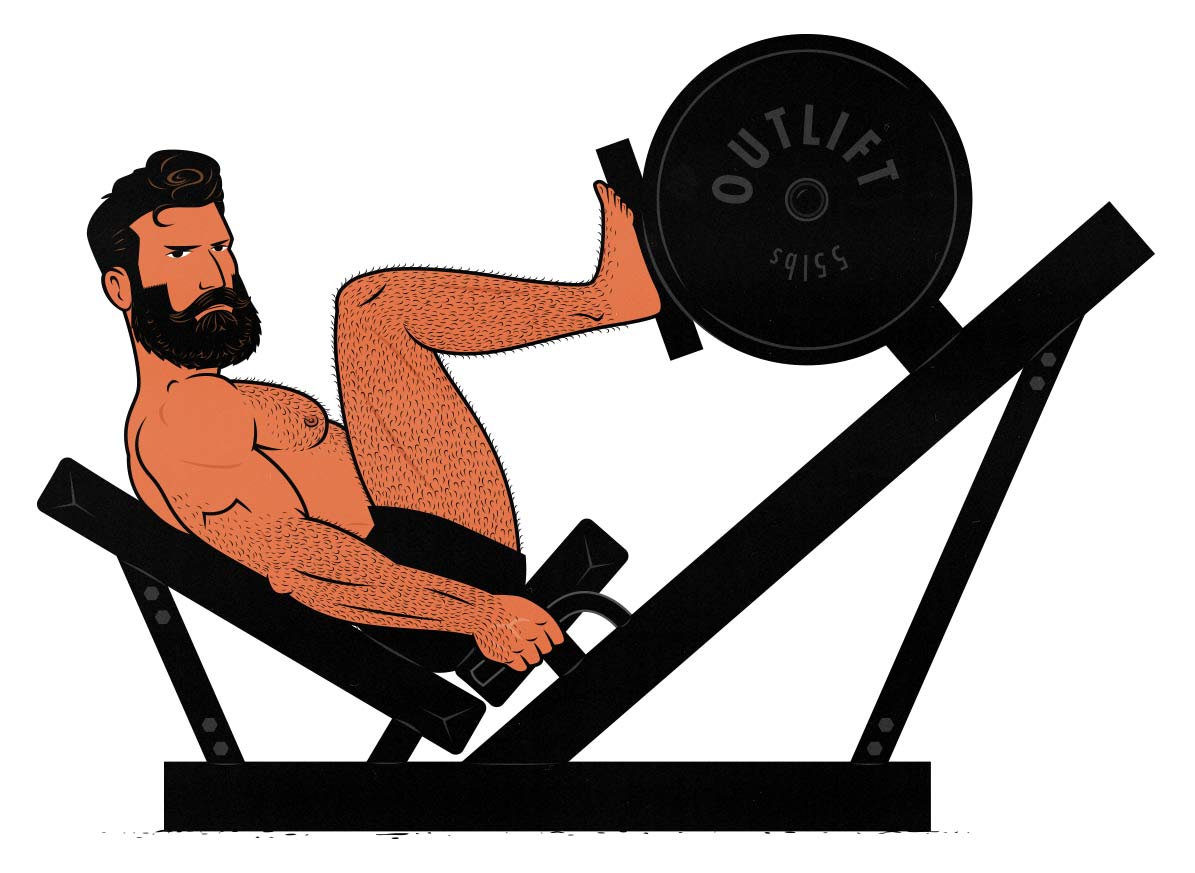

Another notable assistance lift for the squat is the leg press, which shines because it allows you to work both legs quite hard, through a large range of motion, and without adding any extra fatigue to your lower back. So if the goal is to get pure lower-body growth, the leg press is a great choice.

Or, if you want to use the squat to emphasize your hips, you can add in some hip-dominant squat variations, such as the low-bar squat.

There are many great assistance lifts for the squat, though:

- The Zercher Squat: for the quads, glutes, traps, and spinal erectors. Lighter than the front squat, and works well in moderate rep ranges.

- The Leg Press: a great exercise for emphasizing quad growth, and extremely popular with bodybuilders—which good reason.

- The Goblet Squat: a lighter front-loaded squat variation that also works the biceps and shoulders.

- The Back Squat: these can make a great main or assistance exercise. Back squats are more hip-dominant than front squats, and so are great for emphasizing the glutes.

- The Hack Squat: which often emphasize the quads, but still work the glutes and spinal erectors fairly well.

The Best Squat Assistance Exercises

With accessory lifts, we’re trying to stimulate the muscles that aren’t being properly stimulated by our main squat variation. Some people may not care about developing all the heads of their quads equally, but if you do, then you might want to include some sort of leg extension. That way we’re taking our hips out of the movement and training just the knee joint. Back squats seem best at making our quads thicker near the hip, whereas leg extensions seem particularly good at making our quads bigger nearer to the knee.

So as a default, leg extensions tend to make for the best quad isolation exercise, since they’re able to work the quads at just a single joint, but there are a few good lighter accessory lifts for the squat:

- The Leg Extension: the leg extension is popular with bodybuilders because they train the rectus femoris, bulking up the quads nearer to the knees, making them look quite a bit more muscular. It’s a good default accessory lift for everyone, though, given that squats don’t train the rectus femoris very well.

- The Split Squat: is great for training the quads while also improving hip stability. It’s popular among athletes for that reason.

- The Bulgarian Split Squat: is a more advanced variation of the split squat that gives the quads even more emphasis. Again, it’s very popular with athletes.

- The Pistol Squat: a good bodyweight squat variation that emphasizes the quads, while improving balance and hip stability. Not necessarily the best for hypertrophy, given the balance component, but they’re quite easy to add into a routine, increasing overall squat volume without accumulating much extra fatigue.

The Horizontal Press

The horizontal press is the movement pattern that encompasses the bench press, push-up, and dip. These are the most popular bodybuilding exercises of all time, and with good reason—they’re fantastic for building an impressive upper body.

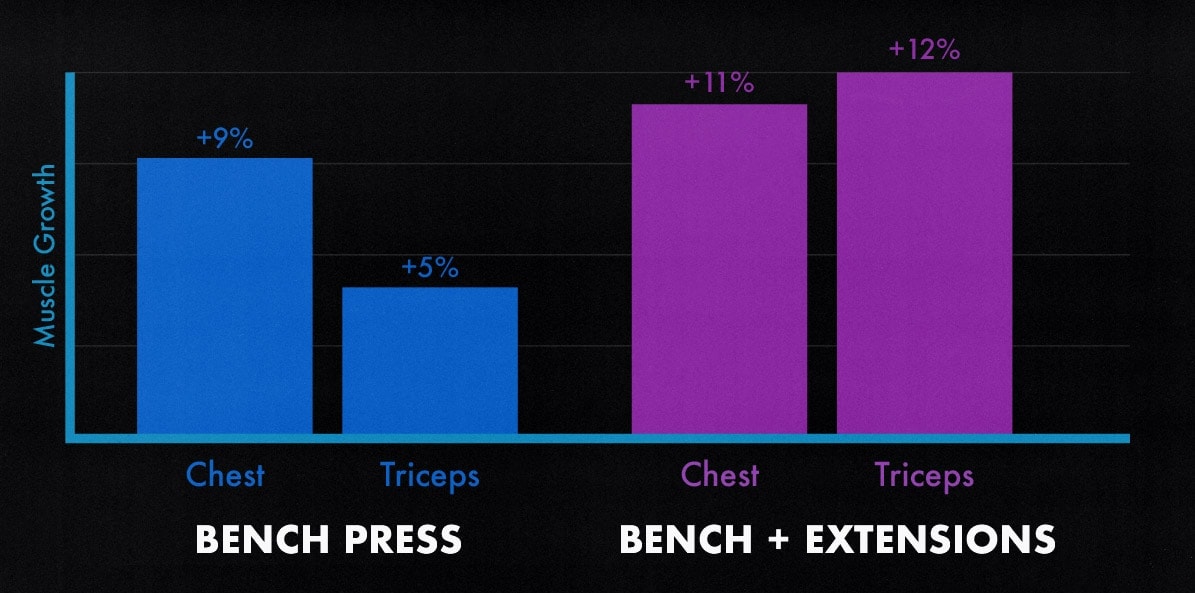

The horizontal press is best for building a bigger chest, especially if we use a wider grip width, but it’s also great for working the fronts of our shoulders, especially if we use a narrower grip width. It’s a good movement pattern for the triceps, too, but as we’ve covered above, it’s mainly the lateral and medial heads that get worked. The long head isn’t able to fully engage in a pressing movement, and so we need to target it with isolation lifts.

The Best Main Horizontal Presses

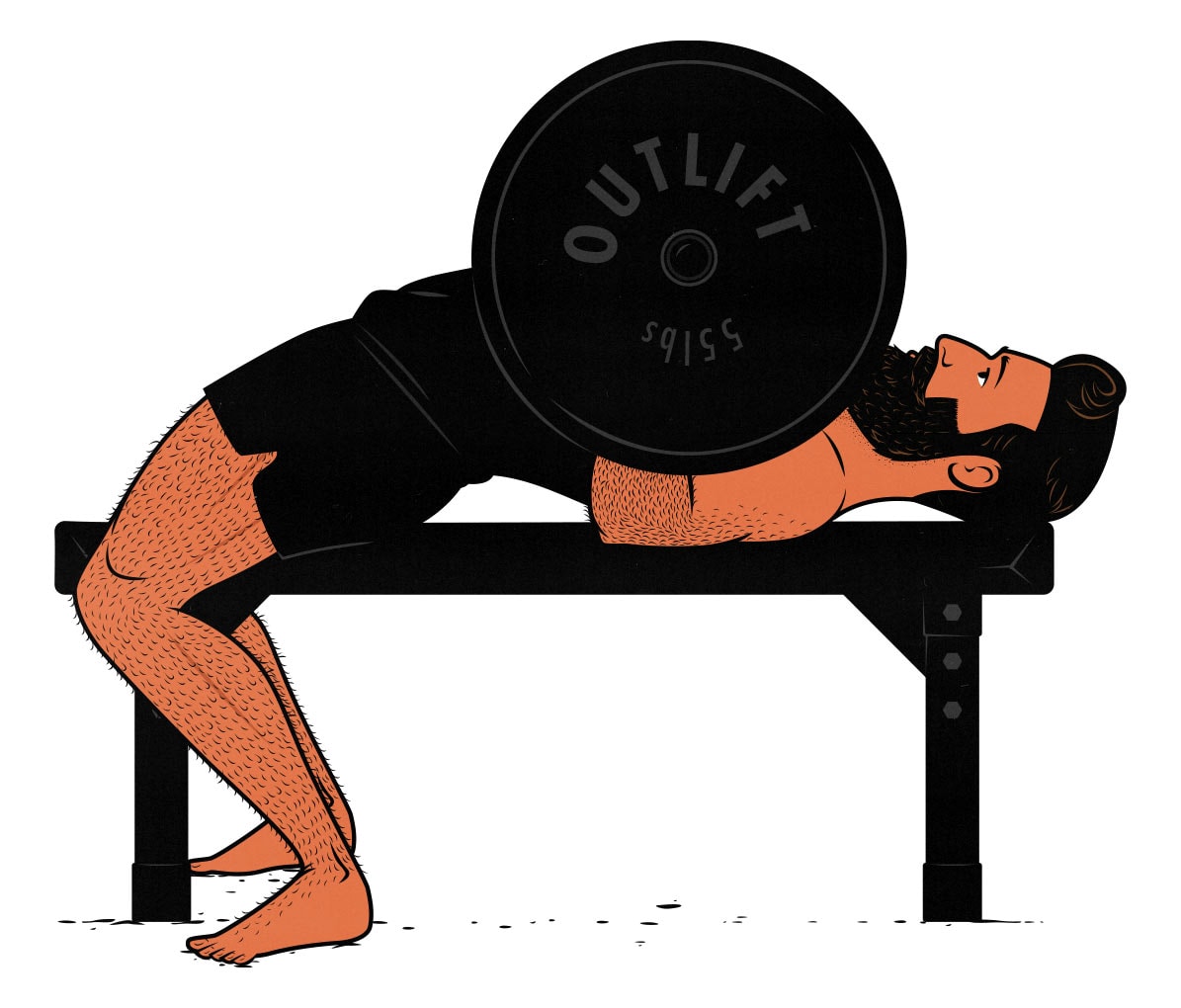

The bench press and push-up are obvious choices as main horizontal pressing variations, as they should be. Both work our chests and front delts through a deep range of motion and challenge them in a stretched position, making them ideal for stimulating muscle growth. As a result, both the push-up and bench press stimulate near-identical growth in our chests and shoulders.

The push-up and bench press do have a few notable differences, though. The push-up requires holding a plank position, and so it does a good job of working the abs, although not always hard enough to stimulate muscle growth. Plus, the push-up doesn’t lock our shoulder blades in a retracted position, and so it also works our serratus muscles.

Instead of picking between the push-up and bench press based on muscle hypertrophy, it often makes more sense to pick the variation that you prefer, feels better on your shoulders, and is easier to progress with. For instance, if you can only do seven push-ups from the floor, you’re well within the hypertrophy rep range, and so there’s no real benefit to doing the bench press until you can do twenty push-ups.

That gives you a few great options for your main horizontal press:

- The Barbell Bench Press: great for stronger lifters, ideal for working the chest, great for working the shoulders, and okay for working the triceps. It works in a variety of rep ranges and can be done with various grip widths, making it quite versatile. A moderate grip width is often the best default.

- The Dumbbell Bench Press: great for those with stubborn chests, since it combines the press of a bench press with the squeeze of a dumbbell fly. However, it isn’t as good for the triceps and is harder to do in lower rep ranges.

- Push-Ups: perhaps the best horizontal press for people who aren’t all that strong yet. It works the same movement pattern as the bench press while also stimulating your abs and serratus muscles.

- Dips: an amazing exercise for working your chest through a deep range of motion.

Best Horizontal Press Assistance Exercises

Once we’ve picked our main horizontal press, we want to find some slightly lighter compound lifts that we can use to increase our training volume and bring up weak points. There are a couple of different approaches you can take:

- The close-grip bench press: for your shoulders, upper chest, and triceps.

- The incline bench press: for your shoulders and upper chest.

- The feet-up bench press: a lighter bench press variation.

- The pause bench press: for extra chest emphasis

- The deficit push-up: a great lift for working the chest through a deep stretch while also strengthening the serratus muscles. Great for building stronger and healthier shoulder joints, too.

Best Horizontal Press Accessory Exercises

The bench press works the chest quite heartily, especially if you use a moderate-to-wide grip and bring the barbell all the way down to your chest. As a result, research shows that most people get fairly complete chest development from the bench press (study).

However, we run into a problem with the our triceps. The long head of our triceps extends our elbow, which can help us press the barbell away from us, but it also extends our shoulder shoulder joint, which pulls the barbell back towards us. If we fully engage the long head of our triceps, then, it can interfere with our bench press. And so it lies fairly dormant.

By combining a chest-dominant bench press with triceps extensions, we get fairly equal growth in both our chests and triceps. It’s a great default exercise pairing. Do your bench press first, then do some triceps extensions afterwards.

If you want to bring in extra chest work, the chest fly is great. Not everyone needs them, but they can be great for bringing up lagging pecs.

That gives us a pretty good list of bench press accessories:

- The skull crusher: a great lift for overall triceps growth, and thus overall arm growth.

- The overhead extension: a great lift for emphasizing growth in the long head of the triceps, which is great for improving arm aesthetics.

- The triceps pushdown: a good lift for building bigger triceps without putting as much strain on your shoulders or elbows.

- The dumbbell fly: the dumbbell fly is great at challenging your mid-chest in a deep stretch.

- The machine fly: a great lift for challenging our chests through a full range of motion, and it often has a fairly flat strength curve, making it good for stimulating muscle growth.

- The cable crossover: a good exercise for training the chest under constant tension, but I suspect dumbbell flyes are better.

The Hip Hinge

There are a few different reasons that people do hip hinges. Most men do them either with the goal of deadlifting more weight or building a bigger posterior chain overall, with just as much emphasis on their traps and spinal erectors as on their glutes and hamstrings. In that case, the deadlift has a lot in common with exercises like the barbell row, where our spinal erectors and traps are just as dominant as our hips and hamstrings.

However, some people choose to use the hip hinge as more of a hip lift, with more stimulus on their glutes and hamstrings instead of sharing it equally with their spinal erectors and traps. In that case, the hip hinge becomes more of a thrusting movement. That’s a good approach, too.

The Best Main Hip Hinge Exercises

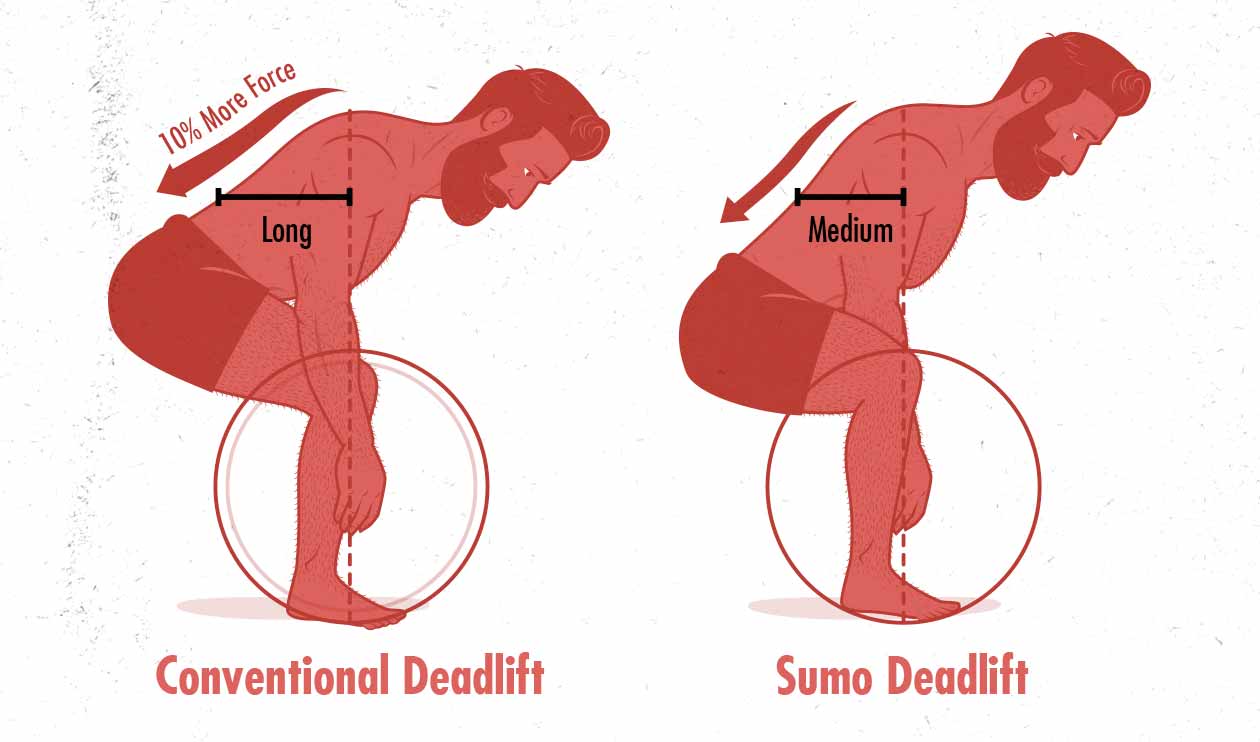

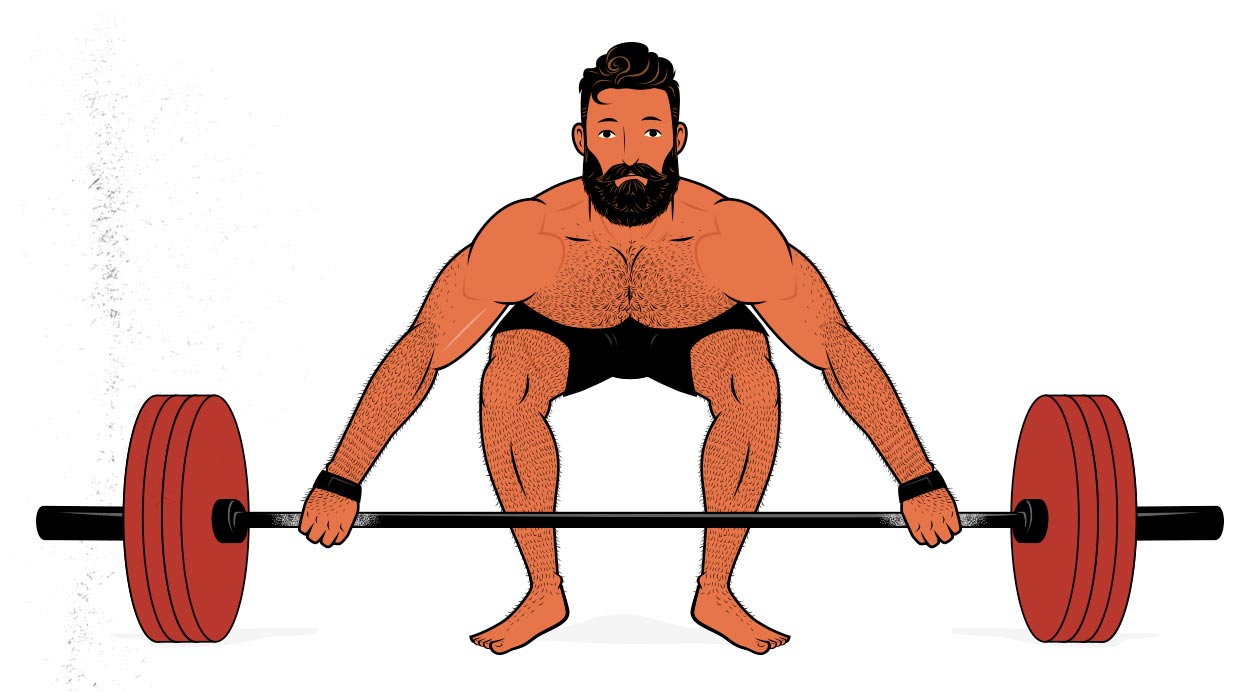

If we’re using the hip hinge to bulk up our entire posterior chain, the conventional deadlift is best. By allowing us to load the heaviest weights, working our muscles through a large range of motion, and by forcing us to lift with a more horizontal torso, we can stimulate a tremendous amount of overall muscle growth, with quite a lot of that muscle growth being in our backs.

For example, if we compare the conventional deadlift against the sumo deadlift, we see that the conventional deadlift has a more horizontal torso and demands more of our lower backs. It also has a larger range of motion, forcing us to do more overall work. This makes it the most fatiguing deadlift variation, but also the best variation for building a bigger back.

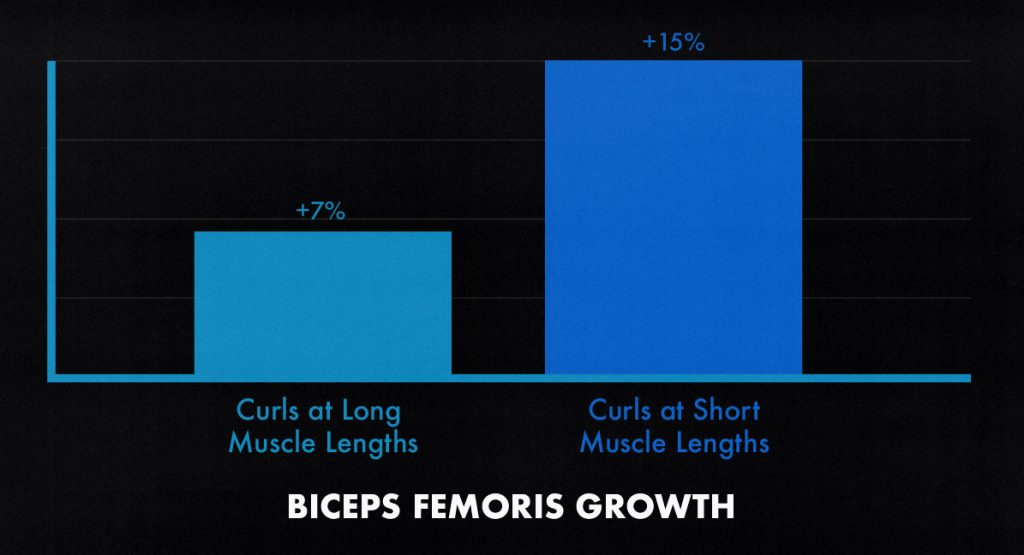

The downside to both conventionl and sumo deadlifts is that the movement at the knees prevents the hamstrings from working as hard. That’s where the stiff-legged “Romanian” deadlift comes in. By keeping your knees stiffer, you can work your hamstrings much harder, making the deadlift better for building a bigger lower body.

Overall, the best main hip hinge variations are:

- The conventional deadlift: ideal for bulking up the spinal erectors, traps, glutes, and hamstrings. It’s also quite metabolically taxing, making it a good lift for improving our general health and fitness. For bodybuilders, general strength, and general health, this tends to be the best variation. For beefier lifters, it also tends to be the heaviest deadlift variation.

- The trap-bar deadlift: can be used as either a hip-dominant or a quad-dominant lift, depending on the amount of hip and knee bend that you use. If you drive your hip backs and deadlift the weight up, it can be very similar to a conventional deadlift, and makes for a great hip hinge. In that case, it makes a great alternative to the conventional deadlift. The range of motion is usually a bit smaller, but it’s also a lot easier to grip, since the handles won’t try to roll out of your hands.

- The sumo deadlift: great for the hips, hamstrings, traps, and also the quads. It’s not as hard on the spinal erectors and the range of motion is shorter, making it less tiring than the conventional deadlift. For thinner lifters, the sumo deadlift is usually the heaviest deadlift variation.

- The Romanian deadlift: ideal for the hips and hamstrings, easier on everything else, and quite a bit less fatiguing. Great for those looking to emphasize hip growth over back growth.

Best Hip Hinge Assistance Exercises

With our assistance lifts, we want to work the main movement pattern but in a way that complements our main lift, giving us a greater exercise variety to minimize joint stress and fatigue, as well as balancing out our muscle growth. For building a bigger posterior chain and spinal erectors, we want to choose exercises that train our backs in a more horizontal position. And since we’re already doing heavy deadlifts, we might want to choose lighter variations to minimize fatigue. One way to do that, if you have the hip mobility for it, is to do wide-grip or snatch-grip deadlifts. The extra range of motion forces us to use lighter weight, but sinking deeper into the lift is great for our entire posterior chain.

For building bigger hips, think of exercises like step-ups, lunges, and hip thrusts. I’m particularly fond of step-ups. They’re easy to set up, easy to master, and great at challenging your hips through a deep range of motion. I’m less fond of hip thrusts. They’re too difficult to set up and put too much emphasis on the contraction.

Overall, here are the best assistance lifts for the deadlift:

- Wide-grip/snatch-grip deadlifts: these increase the range of motion, giving the hips and hamstrings a deeper stretch and putting the back more horizontal at the bottom. This makes wide-grip deadlifts quite a bit lighter and easier to recover from while still stimulating a ton of overall muscle growth.

- Romanian deadlifts: ideal for giving the hips and hamstrings some extra volume without accumulating much extra fatigue.

- Good mornings: like Romanian deadlifts, good mornings are great for the hips and hamstrings. But since the bar is resting on our backs, they don’t tire out our hands and mid-back muscles as much.

- The Step-Up: the step-up is great for training both the hamstrings, glutes, and quads, which makes it great for improving conventional deadlift strength.

- Lunges: to train the hamstrings while improving hip stability. These are great exercise for building thicker thighs and hips.

Best Hip Hinge Accessory Exercises

Accessory lifts are here to fill in the gaps. You could do extra work for your posterior chain, such as hyper-extensions and barbell rows. If your traps are lagging behind, you might want to include some shrugs. And if you haven’t been doing Romanian deadlifts, your hamstrings might benefit from hamstring curls.

That gives us the following hip hinge accessory lifts:

- Leg curls: these train the hamstrings via knee flexion, which isn’t done very well with the compound lifts. As a result, these are a great default accessory lift for bodybuilders looking to build bigger hamstrings. Seated leg curls train the hamstrings at longer muscle lengths, making them better the lying hamstring curls.

- Barbell rows: these train the hips, hamstrings, and spinal erectors isometrically while emphasizing upper back growth with the rowing movement. These are great for improving overall general strength and muscle size. Powerlifters often do “Pendlay” rows from the ground, emphasizing their spinal erectors. A good default for gaining muscle size is to do “bodybuilder” barbell rows, starting from a Romanian deadlift position and rowing from there.

- Hyper-extensions: to build a stronger lower back and hips. Great for improving deadlift strength. Both standard and reverse hyper-extensions are great.

- Donkey kicks: to build bigger hips and hamstrings while improving hip stability.

- Shrugs: to build bigger traps. Mind you, shrugs are often overkill, given that the traps are worked hard by almost every deadlift and overhead press variation. If you use our overall system to build muscle, your traps will probably be one of your best muscle groups, even without shrugs.

- Hip thrusts: to emphasize glute growth.

The Vertical Press

The vertical press mainly works our upper chests, shoulders, upper backs, and triceps. It has quite a lot of overlap with the horizontal press but with more emphasis on the shoulders and less on the chest.

The incline bench press has quite a lot in common with the flat bench. The overhead press is quite a bit different, working your traps, abs, and serratus muscles. I think it makes for a great default.

Best Main Vertical Press Exercises

With strength training, the default vertical press is the standing overhead press, done with either dumbbells, kettlebells, or a barbell. It builds strength from the tips of our toes all the way through our hands, it allows us to move quite a lot of weight, and it’s a great lift for bulking up our shoulders, traps, and even our upper chests.

However, not everyone has the shoulder mobility to comfortably press a barbell overhead. You can probably develop that mobility, but in the meantime, you can do seated dumbbell presses, incline bench presses, and landmine presses.

The best main vertical press variations are:

- The Barbell Press: ideal for bulking up our shoulders and traps, great for strengthening our external rotators and overall upper back, and good for our upper chests, triceps, and abs. However, they require quite a lot of shoulder mobility and core stability to perform properly, making them a fairly advanced lift.

- The Dumbbell Press: just as good as the barbell press for working the shoulders, upper back, and core, but not as good for the triceps. They’re often easier for beginners to learn, especially when done one arm at a time (or seated).

- The High-Incline Bench Press: great for people who don’t have the shoulder mobility or core stability for the overhead press, but not as good for working the side delts, traps, external rotators, or core.

Best Vertical Press Assistance Exercises

Once you’ve chosen your main vertical press, you can choose smaller variations to add some extra variety. If you’ve chosen the barbell overhead press as your main lift, maybe you want to do some one-armed dumbbell overhead presses as well, or perhaps the incline bench press. The main thing is choosing another compound lift that works the same movement pattern and feels good on your shoulders.

Here are a few good vertical press assistance lifts:

- The One-Arm Press: great for emphasizing shoulder growth while training core stability. These can be done with dumbbells or kettlebells.

- The High-Incline Bench Press: great for giving the upper chest, front delts, and triceps some extra work, but not as good for the core, traps, or for improving our shoulder health.

- The Close-Grip Bench Press: challenges similar muscles to the incline bench press but at longer muscle lengths, likely making it even better for stimulating muscle growth.

- The Landmine Press: the landmine press is a similar movement to the incline bench press while allowing the shoulder blades to roam freely. It’s a great lift for improving shoulder health and stability and pairs well with the overhead press.

- Push-Ups: trains the chest, upper chest, front delts, and shoulders, similar to the close-grip bench press, except our shoulder blades can roam freely, which is great for improving our shoulder health and stability.

Best Vertical Press Accessory Exercises

With our accessory lifts, we want to work the muscles that aren’t being fully engaged by the main variation. In this case, similar to the bench press, there’s too much movement in the shoulder joint for the long head of our triceps to be fully engaged, so we can benefit from adding triceps extensions.

But the bigger purpose of the vertical press is to work our shoulders. As we press the weight overhead, it’s mainly our front delts doing the work, so we can add in extra work for our side delts, which will help us build broader shoulders. There are only a couple of lifts where our side delts are the limiting factor: the lateral raise and the upright row.

Finally, if we’re using the vertical press to build bigger shoulders, then we should also consider our rear delts. They’re engaged by overhead pressing, but they aren’t worked anywhere near hard enough to stimulate much muscle growth. We can benefit, then, from some reverse flyes or face-pulls.

Here are some good accessory lifts for the vertical press:

- The lateral raise: the lateral raise is the quickest, easiest, and safest isolation lift for the side delts, which often lag behind, making it a great default accessory lift for the vertical press. Plus, it works the upper traps quite well, too, which is great for bodybuilding aesthetics.

- The overhead triceps extension: good for bulking up the long heads of the triceps, which aren’t fully stimulated by the overhead press. The advantage is that they train the triceps at extremely long muscle lengths, which is great for stimulating growth. The downside is that they can be hard on the elbows, at which point skull crushers or cable pushdowns might be the wiser choice.

- The upright row: great for bulking up the side delts, rear delts, and upper back muscles. It’s the biggest side delt movement, and a great bodybuilding exercise. The only downside is that some people find that it hurts their shoulder joints. Grinding through that discomfort week after week can cause shoulder impingement problems, so if you notice shoulder discomfort, it’s better choose a different lift.

- The reverse fly: great for bulking up the rear delts, which will often lag behind, especially in routines that don’t emphasize horizontal pulling. Building bigger rear delts give us rounder “capped” shoulders, which is an important aspect of bodybuilding aesthetics.

- The face-pull: great for bulking up the external rotators, traps, and rear delts, making them a good exercise for improving shoulder health and stability.

The Vertical Pull

Vertical pulls are great for your upper back, and depending on how you do them, they can also be great for building bigger biceps.

Hip hinges and horizontal pulls also work our back muscles, but at shorter muscle lengths, and often with more emphasis on the spinal erectors. It’s the vertical pulls that are best for bulking up our upper backs, which helps give us wider and more v-tapered physiques.

The Best Vertical Pull Variations

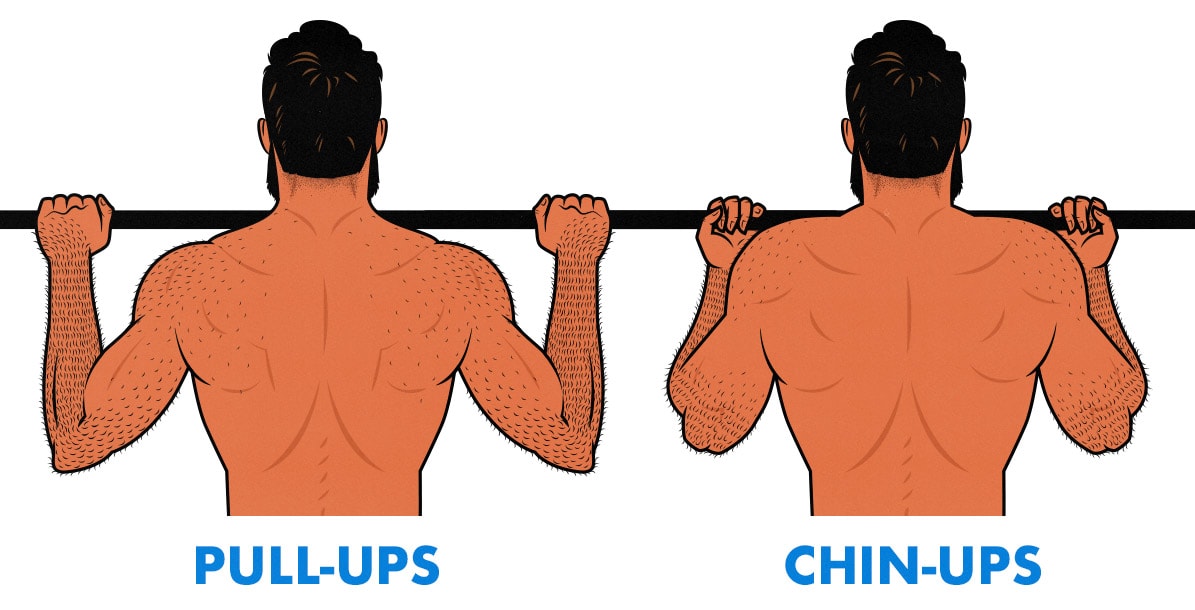

The two most popular variations of the vertical pull are the chin-up and the pull-up. The difference between between the two is simply the grip. Pull-ups use an overhand grip, whereas Chin-ups use an underhand or neutral grip:

When you use an overhand grip, you can start with wider elbows and pull them in closer to your body, working your lower lats. When you use an underhand or neutral grip, your biceps are in a better position to help pull you up, making it a bigger compound exercise.

Chin-ups are often done on a straight chin-up bar, but that can aggravate some people’s elbows. You might find it feels better if you use an angled bar or gymnastic rings. That’s perfectly fine. That’s just as good for building muscle.

That gives us a few good main variations:

- Chin-ups: the biggest vertical pulling exercise, great for bulking up your upper back and lats. You can do them with an underhand, angled, or neutral grip.

- Pull-ups: a slightly smaller back exercise that can work well for people who want to bring up their lower lats.

- Lowered chin-ups: great for learning how to do chin-ups.

- Lat pulldowns: great for people who can’t do chin-ups yet.

The Best Vertical Pull Assistance Exercises

With your assistance lifts, choose lighter variations that still do a great job of stimulating growth in your target muscles. Pull-ups and lat pulldowns are perfect here, but I also recommend including some rowing.

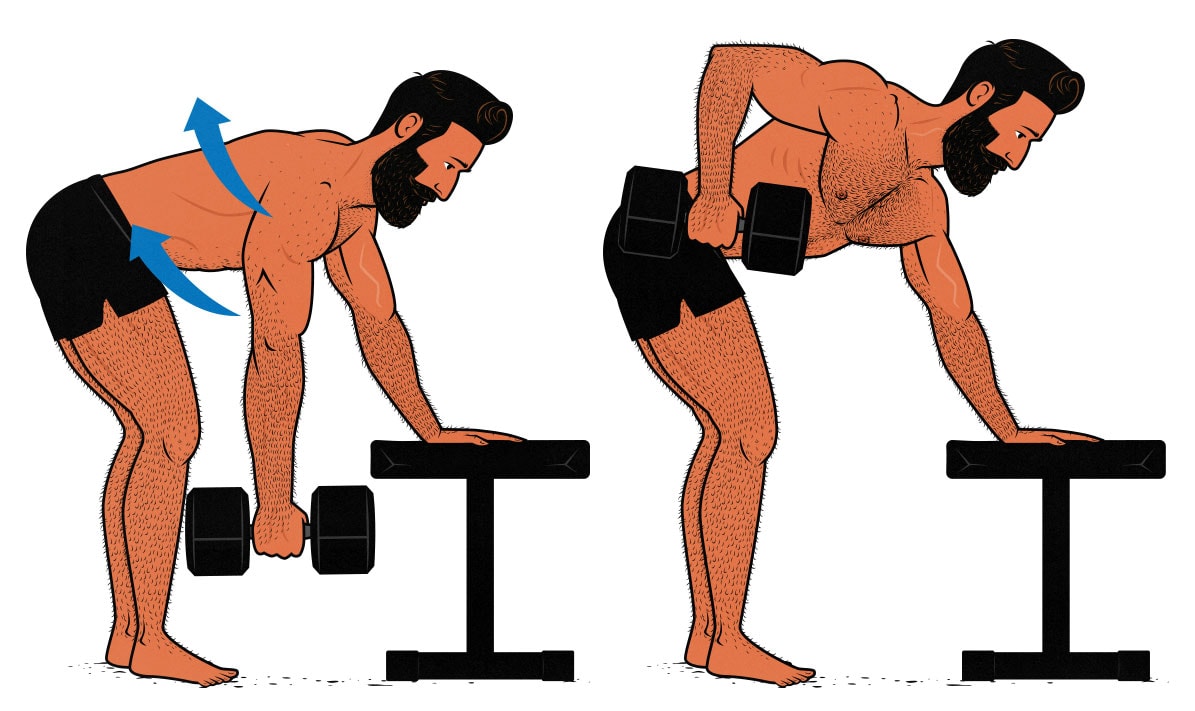

One of the better row variations is the 3-point dumbbell row. You support your spines by planting your hand on a bench, and you row the dumbbell through a huge range of motion, getting a nice stretch on your traps at the bottom and a full contraction at the top.

Here’s a list of the best assistance exercises:

- The pull-up: great for working our lats through a deep stretch.

- The overhand lat pulldown: great for working our lats through a deep stretch and allows for more flexible loading than the pull-up.

- The underhand lat pulldown: great for working our upper backs and biceps through a large range of motion, and allows for more flexible loading than the chin-up.

- The one-arm lat pulldown: works the lats and biceps one arm at a time, making it easier to establish a mind muscle connection, as well as allowing for an even deeper range of motion.

- The 3-point dumbbell row: does a great job of working the muscles in the mid back while giving the lats some extra stimulation.

- The chest-supported t-bar row: has perhaps the best strength curve of all back exercises and works the mid back, lats, and forearms quite hard.

The Best Vertical Pull Accessory Exercises

With your accessory lifts, consider muscles that aren’t properly stimulated by the bigger compound exercises. With the chin-up, the muscles that need a bit of extra love are often the biceps.

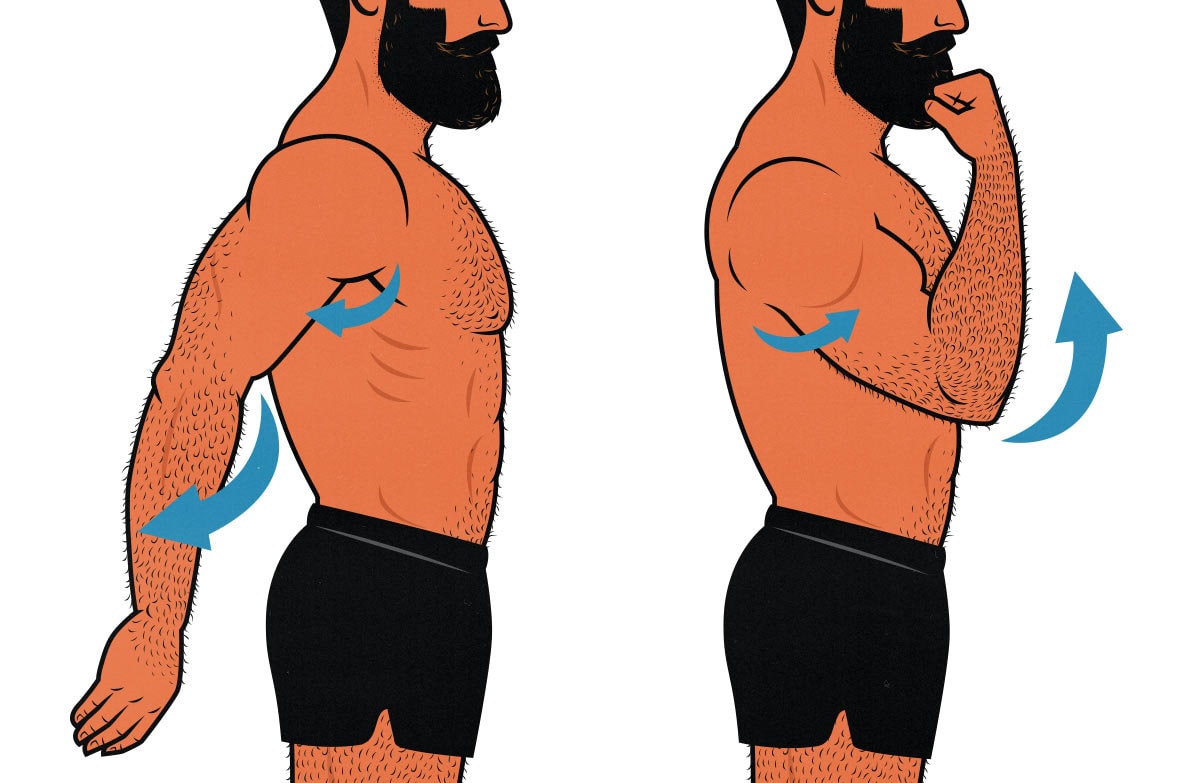

Your biceps flex your arms, helping with pulling exercises, but they also pull your elbows forward, interfering with pulling exercises (full explanation):

The best way to train your biceps, then, is with an exercise that keeps you elbows still or lets them drift forward. That exercise is the biceps curl.

You could also choose accessory exercises like face pulls. Your rear delts and rotator cuff are worked plenty by compound exercises, but you might still want a bit more.

That gives us the following accessory exercises for the chin-up:

- The barbell curl: great for working the biceps in a balanced way and with a heavy load, stimulating a ton of overall biceps growth.

- The dumbbell curl: great for working the biceps while allowing the wrists and elbows to work through a natural range of motion. Great for bulking up the biceps without beating up the elbows. I especially like lying biceps curls.

- The incline curl: great for training the long heads of the biceps at longer muscle lengths, which complements the chin-up well.

- The straight-arm lat pulldown: great for focusing on the lats (and the long head of the triceps), working them with constant tension, a deep stretch, and through a large range of motion.

- The pullover: another great lift for focusing on the lats (and the long head of the triceps), working them with constant tension and a deep stretch.

- The rear-delt fly: a simple lift that works the rear delts, which can sometimes lag behind.

Extra Isolation Exercises

Some isolation exercises don’t slot neatly under any compound exercises. There are four muscle groups we haven’t addressed yet:

- Neck: trained with neck curls, neck extensions, and neck side raises. Neck bridges can also work, but they tend to be a bit harder on our spines, giving them a lower stimulus-to-fatigue ratio and potentially a higher risk of injury. For more, we have a full article on neck training.

- Forearms: your forearms are trained by compound exercises. Your forearm flexors are trained with curls. Your forearm extensors are trained with lateral raises. Your brachioradialis is trained with pull-ups. Still, you might want to include some forearm curls, hammer curls, and/or reverse curls. More on forearm training here.

- Calves: trained with calf raises. Standing calf raises train our calves at longer muscle lengths, so they tend to be better for building muscle. For a better calf stretch at the bottom of the lift, it helps to raise the toes up, doing “deficit” standing calf raises.

- Abs: trained with planks, crunches, and leg raises. However, keep in mind that our abs are trained to a certain extent with almost every compound lift, and so many people won’t need any isolation work. For more, we have a full article on building bigger abs.

Keep in mind that you don’t need to do all of these lifts all of the time. You might want to spend a few months catching your neck or forearms up and then let them coast from there. Or not. It’s up to you.

Summary

The vast majority of your muscle growth will come from the big compound hypertrophy exercises. Choose a couple of exercises from each main movement pattern:

- Squats, such as goblet squats, front squats, and high-bar squats.

- Horizontal presses, such as bench presses, push-ups, and dips.

- Hip hinges, such as conventional and Romanian deadlifts.

- Vertical presses, such as incline bench presses and overhead presses.

- Pulls, such as chin-ups, pull-ups, pulldowns, and rows.

Then fill in the gaps with isolation lifts, especially for the muscles you’re most eager to grow. Here are some popular examples:

- Overhead triceps extensions for your triceps.

- Lying biceps curls for your biceps.

- Neck curls for your neck.

- Lateral raises for your side delts

- Standing calf raises for your calves.

- Crunches for your abs.

In our Outlift Intermediate Hypertrophy Program, we give you 3-day, 4-day, and 5-day workout routines. Each has an easy and hard mode. We’ve chosen all the best compound and isolation exercises, and each has a dropdown menu that lets you pick from a list of suitable variations. The guide explains the pros and cons of every exercise in the program.

We include optional exercises, too. If you want to bulk up your calves, choose calf raises. If you’d rather focus on building broader shoulders, choose lateral raises instead. We give you a template, and then you can customize it to suit your goals.

Awesome article. I think the most important part is knowing if the exercise is actually working the right muscles and the questions included in the last section are helpfull, especially feeling the tension at the bottom of the lift. I will keep that next time. Keep it up. Thanks for posting it.

Thank you! 🙂

Great article, and right on time too because I just purchased Outlift and start Phase 1 on Monday. I’d be interested in a short followup article discussing *when* to program assistance and accessory lifts.

E.g. Do you perform curls after you’ve pre-exhausted your biceps with chinups, or do curls on a different day? Is it best to program your assistance zercher squats on a different day than your main front squats to spread out the volume, or is there some benefit to doing them in the same session? Etc. I suspect there’s pros and cons to each scenario depending on your goals (bring up a lagging body part vs. get extra volume without too much fatigue).

I’m taking the 4-day hard Outlift routine and spreading it out to a 6-day hard routine (I prefer 6 short-ish workouts per week). I have a reasonable schedule laid out, but would be really interested in seeing you discuss the pros and cons of when to layer assistance/accessory lifts on within a week’s workout.

Hey Kevin, thank you! And that’s awesome. I really hope you like the program.

We’ve got an article on exercise order that might help. But the Outlift Program already has the lifts organized in the best order. You can just pick your lifts from the dropdown menus and you’ll be all set 🙂

Whether to do your assistance/accessory lifts on the same day as a main lift is a tricky question, yeah. Definitely pros and cons to doing it either way. If you’re doing less than 3 sets for a muscle group in a workout, especially if it’s in lower rep ranges, might be nice to toss an extra lift in there to ensure that you have enough volume to stimulate muscle growth. If you’re doing more than 8 sets for a muscle, especially in higher rep ranges, might start making more sense to split them up. But it definitely depends. We talk about splitting up volume in our article on training volume. Again, though, we’ve done our best to do that work for you. Outlift is already organized in a way that should be ideal. But like you said, it depends on the situation and your goals. If someone wants to focus on their arms, for instance, we might have several arm exercises each workout.

I’m working on a 5-day routine to add to the Outlift package. It’d be fun to make a 6-day routine, too, so that you don’t need to spread it out yourself. Maybe that can come next.

Thanks! Somehow I had missed that Exercise Order article. That helped a lot.

I really like the look of the 4-day hard Outlift program where you have everything already laid out. I just need to keep my workouts to 30-35 minutes to fit my schedule (working out at home), so 6 days is the sweet spot for me. I’d definitely be interested in seeing a 5-day or 6-day Outlift routine.

Ooh, I’m excited to see the 5-day routine. I think the 4-day Hard routine is perfect for me at present (I haven’t had to add sets yet either), but it would be great to have something to switch to when I need more volume to keep growing.

Delighted to see the Zercher have its moment in the sun! Zerchers have been very good for me. Wish the trap bar deadlift (which I realize is part squat and part deadlift) could have its moment too; it’s so good for those with finicky backs.

Also might mention that I (and several other middle-age gym friends) were unable to do pull-ups/chin-ups until discovering the resistance band training method. Loop a long band (or two) over the bar and either step into it with one foot (short guys) or hook it around a bent knee (tall guys). Gradually use thinner and fewer bands. This got me over the hump, after over two years of trying everything else. I still do band assists for extra volume sometimes, when I’m too tired to rep out another bodyweight pull-up.

Fantastic article; this is one of those archival reference-type articles! Thanks.

Thank you, Doc G. Yeah, Zercher squats are a blast!

If you go to our article on the deadlift, we talk about the pros and cons of the trap-bar deadlift. If you do it with the same movement pattern as a conventional deadlift, there are a few neat advantages to it, and no real disadvantages at all. It’s a great lift. I would just consider it a conventional deadlift with a different barbell, at that point. Similar to how you can do high-bar squats with a safety bar.

But you’re making a really good point, and now that you’re mentioning it, this article should be able to stand on its own without people needing to read the other ones. I’ll add the trap-bar deadlift and safety squats 🙂

For learning how to do the chin-up, yeah, that’s a good technique for it. I taught my wife how to do them that way, too. I want to make another version of this article over on the Bony to Beastly and Bombshell blogs about how to progress towards the main lifts. This article is meant more for the seasoned lifter trying to optimize their training, not for someone still newer to it. You’re totally right, though. Just keep in mind that resistance bands make the resistance curve worse. The beginner is already too easy and the top is already too hard. Not that you shouldn’t ever use the resistance band, just that once you don’t need it anymore, regular chin-ups are better, even if it means lifting in lower rep ranges.

Re bands — right you are! Great for getting you there, shouldn’t be a staple of anyone’s routine after that. Also I kinda forgot this was the Outlift blog, not for newbies =)

Gran página con artículos muy completos, gracias por toda esta información, saludos desde España.

Gracias, Iván! Saludos desde México 🙂

Well-written and thorough article. I wanted to share an overlooked exercise when it comes to the hip hinge: the kettlebell swing. I think it’s a great assistance lift or accessory lift. Kettlebell exercises aren’t part of the traditional weightlifting repertoire, but the swing is something that can’t be replicated with a barbell or even a dumbbell. Working to accelerate the bell at the outset and then decelerate it before accelerating it again makes the swing a grueling exercise if you go heavy. And you can’t get a fuller range of motion with a hinge exercise. Not only will it work your posterior chain, but it’s a highly challenging exercise for the grip. I swear by the kettlebell swing and just thought I’d share it with you and your readers.

Hey Anthony, that’s a great point! We use the kettlebell swing in our women’s program, and I’ve done quite a lot of it myself, especially when training at home. I think it has a lot of use. Super cool lift.

I’m not sure it’s a great hypertrophy lift, though. Not that it’s terrible, just that it’s not ideal for stimulating muscle growth. It’s more of a power lift, not unlike Olympic lifting. There’s no real eccentric portion, and even the concentric portion is fairly brief and explosive. That’s not to knock it, though. It just has a different purpose.

Let me double check on that, though. Maybe it should be here. I do really like it.

Typo: “but htey aren’t worked”

Thank you! Fixed 🙂

What kind of program would you recommend for an overweight guy that isn’t skinny fat? I know lifting is the best way to hit my goals to lose fat. Just trying to find the right way to do that.

Great article Shane! What would you think of a program that only focuses on one of the big 5 movements each day, like so:

•Monday: Bench press, close-grip bench press, and skull-crushers.

•Tuesday: Front squat, Zercher squat and split squat.

•Wednesday: Chin-up, underhand row, bicep curls.

•Thursday: Deadlift, wide-grip deadlift, barbell rows.

•Friday: Barbell press, close-grip bench press, lateral raises.

•Saturday & Sunday: Rest days.

Thanks!