Are Chin-Ups/Pull-Ups Good for Your Biceps?

Chin-ups and pull-ups are heavy compound lifts, allowing you to heavily load your biceps while working them through a full range of motion. But they also train your back muscles, and some of those back muscles might fail before your biceps get worked hard enough. In that case, biceps curls might be the better biceps exercise.

Fortunately, a study comparing pull-downs with biceps curls found that they both stimulate about the same amount of biceps growth (study). Pull-downs work your biceps in the same way as chin-ups and pull-ups, so I suspect they’re similarly effective.

But there’s some nuance here. The short head of your biceps can work just fine during pulling exercises, but the long head can’t. The long head stabilizes the shoulder joint, so it can’t engage properly during pulling movements. It will grow faster if you do biceps curls.

Then, we need to consider that the distal portions of your biceps (closer to the elbow) grow faster when you challenge them at long muscle lengths (full explanation). Some types of biceps curls are better for that.

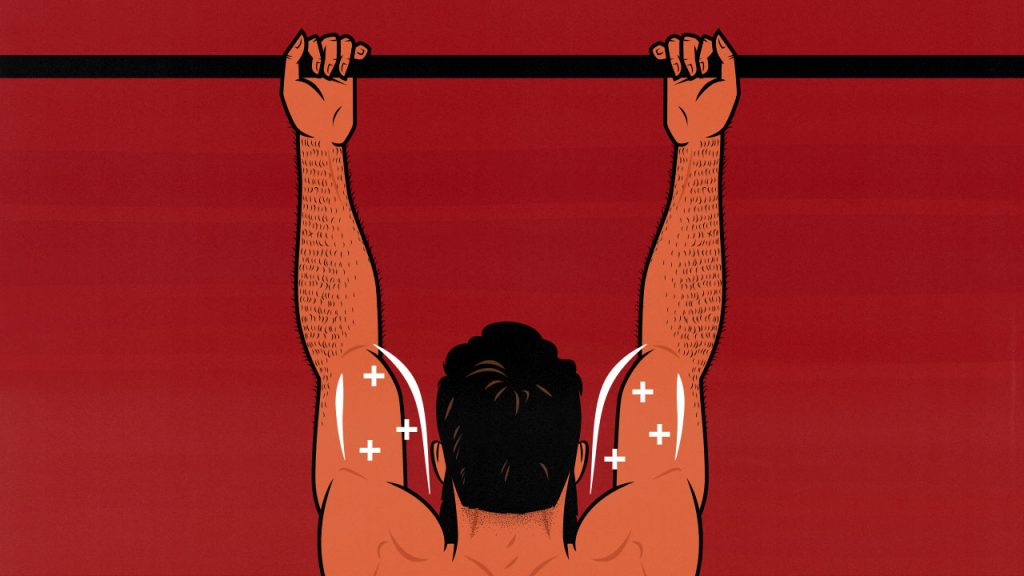

Chin-Ups for Biceps Growth

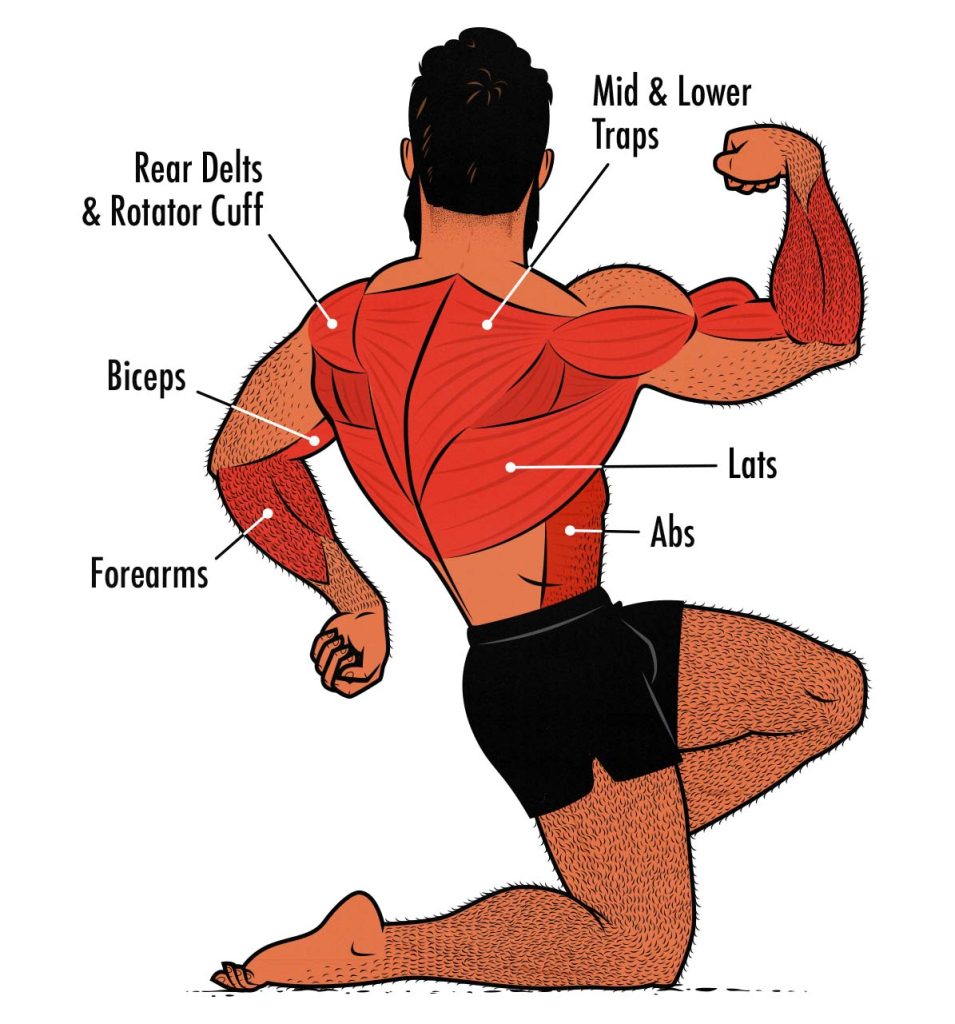

Chin-ups are big compound exercises that work most of the muscles in your back, as well as your abs, biceps, forearms, and other elbow flexors:

Chin-ups can be a great biceps exercise, especially for the short head. They’re a big, heavy compound lift that works your biceps through a full range of motion. There are a few ways to do them:

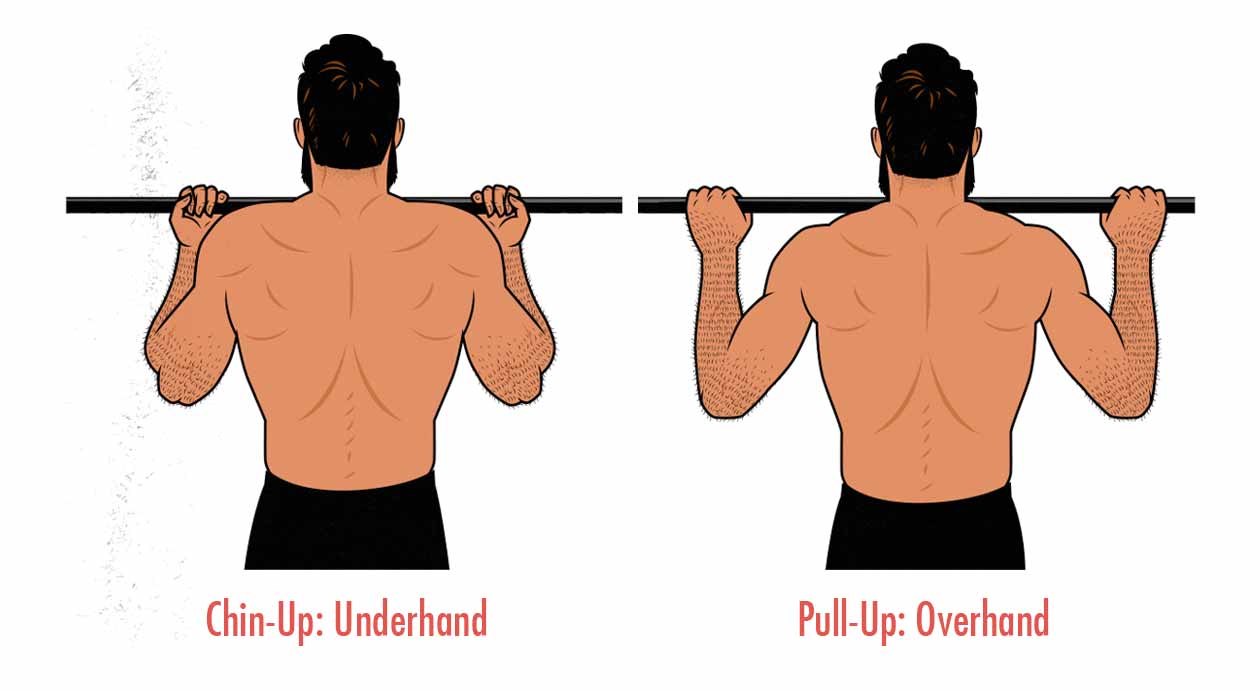

- With underhand chin-ups, you’re working your biceps very similarly to a barbell curl. Your biceps are in a great position to help you pull your body up.

- With an overhand pull-up (or lat pulldown), your biceps are twisted around like a reverse curl. This stretches them out further but gives them less leverage. Your biceps won’t be as strong, but they might still work equally hard, and it’s possible you’d stimulate the same amount of growth.

- With an angled grip, it’s similar to doing curl-bar curls.

- With a neutral grip, it’s similar to doing hammer curls.

It’s hard to say which type of chin-up works your biceps hardest. If we look at the muscle-activation (EMG) research of Bret Contreras, PhD, chin-ups give you about 50% better biceps activation than pull-ups:

- Chin-up: 107 mean biceps activation, 205 peak

- Pull-up: 65 mean biceps activation, 145 peak

But that’s just EMG research. It isn’t very reliable, especially when muscles are being worked at different lengths. It could be that the longer muscle lengths you get with overhand pull-ups more than make up for the lower levels of biceps activation.

Biceps Curls for Biceps Growth

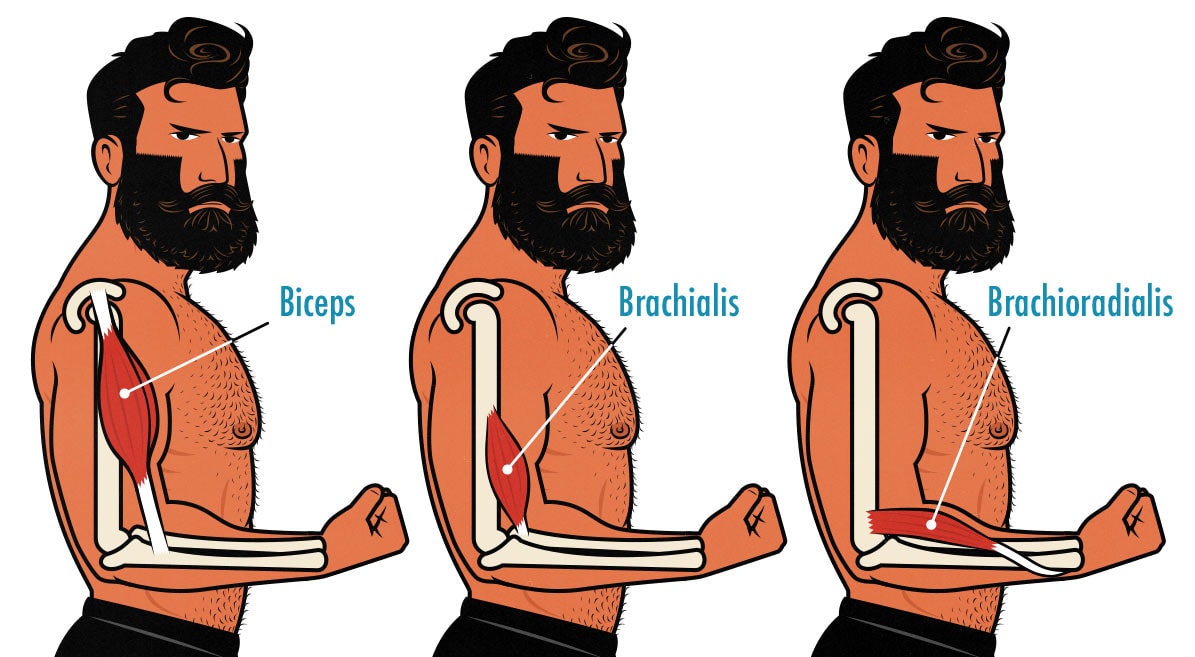

Biceps curls keep your shoulder joint stable, allowing you to focus on contracting your biceps and better engaging the long head. Bodybuilders call biceps curls an “isolation exercise,” but you aren’t just working your biceps. You’re also working your postural muscles, brachialis, brachioradialis, and forearm flexors.

You can probably bias the different muscles by changing your grip. An underhand grip (barbell curls) is thought to be better for your biceps, a neutral grip (hammer curls) is thought to be better for your brachialis, and an overhand grip (reverse curls) is thought to be better for your brachioradialis. That seems likely, though it’s hard to say for sure.

What’s more important is finding a variation that lets you challenge your biceps at long muscle lengths (full explanation). Regular biceps curls are perfectly fine for that, especially if you lift explosively, putting your full effort into “throwing the bar through the ceiling” right from the beginning of the range of motion:

You can also choose biceps curl variations that challenge your biceps even more under an even deeper stretch, such as lying biceps curls. That’s my favourite variation, especially for the long head.

How to Build Bigger Biceps

The best way to build bigger biceps is to combine pulling exercises with biceps curls:

- Start your workout with chin-ups, pull-ups, or lat pulldowns. Those exercises will work your rear delts, upper back, and lats, along with your biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis, and forearms. They’re especially good for the short head of your biceps.

- Then, do biceps curls. Biceps curls are great for your biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis, and forearms. They’re especially good for the long head of your biceps.

For example, Gentil and colleagues found that doing biceps curls after lat pulldowns produced nearly 60% more arm growth than doing just lat pulldowns (study).

Both chin-ups and curls count as volume for your biceps. So do lat pulldowns and other vertical pulls. Rows aren’t as good for your biceps, so I wouldn’t count them (full explanation). You should do somewhere between 8–22 sets for your biceps per week. You can go even higher if your particularly desperate to build bigger biceps.

Anywhere from 6–20 reps per set is fantastic for stimulating muscle growth. You could go even heavier on some sets of chin-ups. You could go even lighter on some sets of curls (especially if you’re doing BFR training).

Ideally, you’d train your biceps at least twice per week. For example, if you’re doing a 5-day split, like a Bro Split, you’d be training your biceps during both Back Day and Arm Day. If you’re doing a 4-day split, like an Upper/Lower split, you’d be training your biceps during both upper body workouts.

For more, we have an article with a few different biceps workouts in it.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds in these principles, check out our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program and Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. Or, if you’ve already gained your first 20–30 pounds, check out our Outlift Intermediate Hypertrophy Program.

Very good info. I’m 92 years old and in excellent shape, except I have osteoporosis, which greatly prevents doing very many chin-ups. But curls are ok. Will continue with both and try to increase my chins-ups now that I have your excellent presentation.

That’s amazing, Jack! Good luck 🙂

Push-Ups tax/grow my Triceps way more than Chin-Ups do my Biceps.

Both with shoulder-width hand position.

Just sharing my n=1.

Thanks for sharing, Fleischman.

You know, that doesn’t surprise me. It was similar for me. My biceps only really started to grow when I added curls to my chin-up routine. Really goes to show that we need to adjust our approach depending on our individual results, in this case making sure to include isolation lifts for the biceps.

You have explained each and every part very clearly such a great article loved it !!!

Thank you, Adarsh!

I don’t understand, the study you linked states that the inclusion of Single Joint exercises in a MultiJoint exercise training program resulted in no additional benefits in terms of muscle size or strength gains in untrained young men. I don’t understand where this 60% more arm growth comes from.

Hey Tom, there are a number of different studies looking into the benefits of isolation lifts (or lack thereof). There are some studies that show no benefits, although more often than not, it’s just something called a type-II error, where the results of the study do show a benefit, it just doesn’t reach statistical significance, and so the authors conclude something along the lines of “the group doing isolation lifts saw 60% more muscle growth, and therefore no significant benefits were found.”

When that happens, it’s tempting to see the 60% extra muscle growth and get excited about the benefits of isolation lifts, but it could just be a coincidence. After all, the study didn’t reach statistical significance. It’s also tempting to think that the study proves that there are no benefits to isolation lifts, but that’s no correct either. The study just didn’t have the statistical power to detect a benefit that may or may not exist.

So if all we had was that one study, we should conclude that we don’t know if there are benefits to isolaton lifts, and we’d hope for more research to come out.

Fortunately, we have much more than that single study. More research has come out. In fact, enough studies have come out that we can pool the data and conduct a meta-analysis, which is what Greg Nuckols, MA, has done. When we do that, we see dramatic improvements in muscle growth from including isolation lifts in our workout routines, especially in the muscles that aren’t adequately stimulated by compound lifts. So, for example, the bench press stimulates the chest quite well. There isn’t really a need for isolation lifts for the chest. But it doesn’t stimulate the long heads of the triceps very well, so there’s quite a large benefit to adding in skullcrushers.

I hope that clears it up.

I had the same question – perhaps it’s because we aren’t subscribed to PubMed but I can’t see the 60% number you’re referencing anywhere in the abstract. Where exactly does that number come from?

If I recall correctly, it’s from the results section of the study. They don’t always give all of the results in the abstract.

Hi Tom

What do you think about drag curls as an alternative to bicep curls

Would you say that they are a more efficient exercise??

Many thanks

Hey Rob, I’m not Tom, but I think I can answer your question.

Drag curls have the elbows moving back behind the body (shoulder extension) while we curl the weight up (elbow flexion). The long head of the biceps pull at both the shoulder and elbow joints, giving us shoulder flexion and elbow flexion. So if we’re adding in shoulder extension, that makes it harder for the long head of the biceps to fully engage. For overall biceps growth, then, I think regular biceps curls are better.

Another option, though, is the incline curl—dumbbell curls done while sitting on an incline bench. With the incline curl, we lock our shoulders in extension while flexing at the elbows. That puts our biceps under a deeper stretch, and since the shoulder joint isn’t moving, it doesn’t stop our biceps from fully engaging. This makes it a great biceps exercise. I’d guess that it may be even better than the regular biceps curl, but it’s hard to say for sure.

Hi Shane, thank you very much for your reply.

As with the chin-up I understand that the drag curl involves shoulder extension which prevents the bicep from fully contracting. However wouldn’t the fact that there is a more even resistance throughout the range of the movement as there is no arc involved and thus a greater resistance in the contracted position make this exercise more productive in some ways?

Also isn’t the bicep be being worked from a stretched position with this exercise??

Okay, I see what you’re saying. The first idea is that challenging our muscles in a contracted position is a good thing, and to be fair, it might be, sometimes. Some experts do think we should choose lifts that challenge our muscles with different resistance curves. For instance, choose an incline curl to challenge our biceps when stretched, and then choose a spider curl to challenge them when contracted. The idea being that the different lifts challenge our biceps in different ways and net us more balanced biceps growth. But I’m not sure that’s the case. Right now, based on the research we have, it seems that challenging our muscles in a stretched position is just flat out better. Unless new information comes out, I’d spend more time doing incline curls instead of doing spider curls.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t use a variety of different exercises, though. For our arms, there’s some value in doing both barbell curls and hammer curls, that way we’re challenging both our biceps and brachialis. Or for our abs, we might want to use both crunches and leg raises to train the top and bottom portions. So it depends on the lift and what you’re trying to do. But with our biceps, I don’t see much point in emphasizing the contracted position. I’m openminded, though. We’ll have to see how the research evolves on this one.

Then, for the specific drag curl exercise, I think it would be better to do incline curls. That way your shoulders are extended all through the lift, your biceps can fully engage, and they’re challenged at longer muscle lengths. Especially if you’re already doing chin-ups, I don’t think most people need more lifts that work the biceps while extending the shoulders. I’d use biceps curls as an opportunity to lock or flex the shoulders, i.e., keeping your elbows in the same position or letting them drift up. That way you can use your full biceps strength to lift the weight.

That’s how I approach it, anyway. It’s hard to know for sure.

I love to superset weighted chin ups with standing barbell curl.

Good article.

That’s a great way to do it 🙂

This is what the deep analysis of good practicner is. The knowledge is too good Shane I loved it I have been also training and studying the body movement loved it keep sharing knowledge.. ❤️