Long-Muscle-Length Training (Aka Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy)

For at least a few decades, bodybuilders have favoured exercises that challenge their muscles at long muscle lengths. “Go deep! Feel the stretch!” The mechanisms weren’t known, and the results weren’t proven, but it seemed that lifting through a deeper range of motion stimulated more muscle growth.

Similarly, 90’s bodybuilders like John Parillo and then Dante Trudel were advocates of “extreme stretching,” where you hold the very bottom position of your exercises, challenging your muscles under a deep stretch.

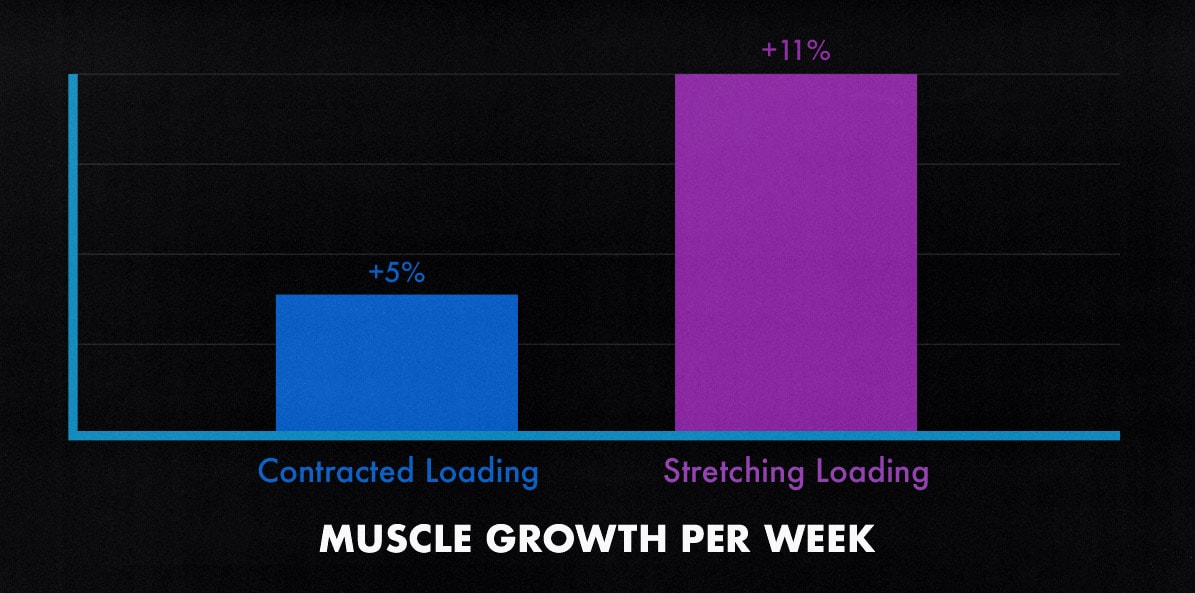

Now, the research is catching up, and the results are even more dramatic than anyone expected. A systematic review of 26 studies found that holding the bottom position of an exercise stimulates nearly three times as much muscle growth as holding the top position.

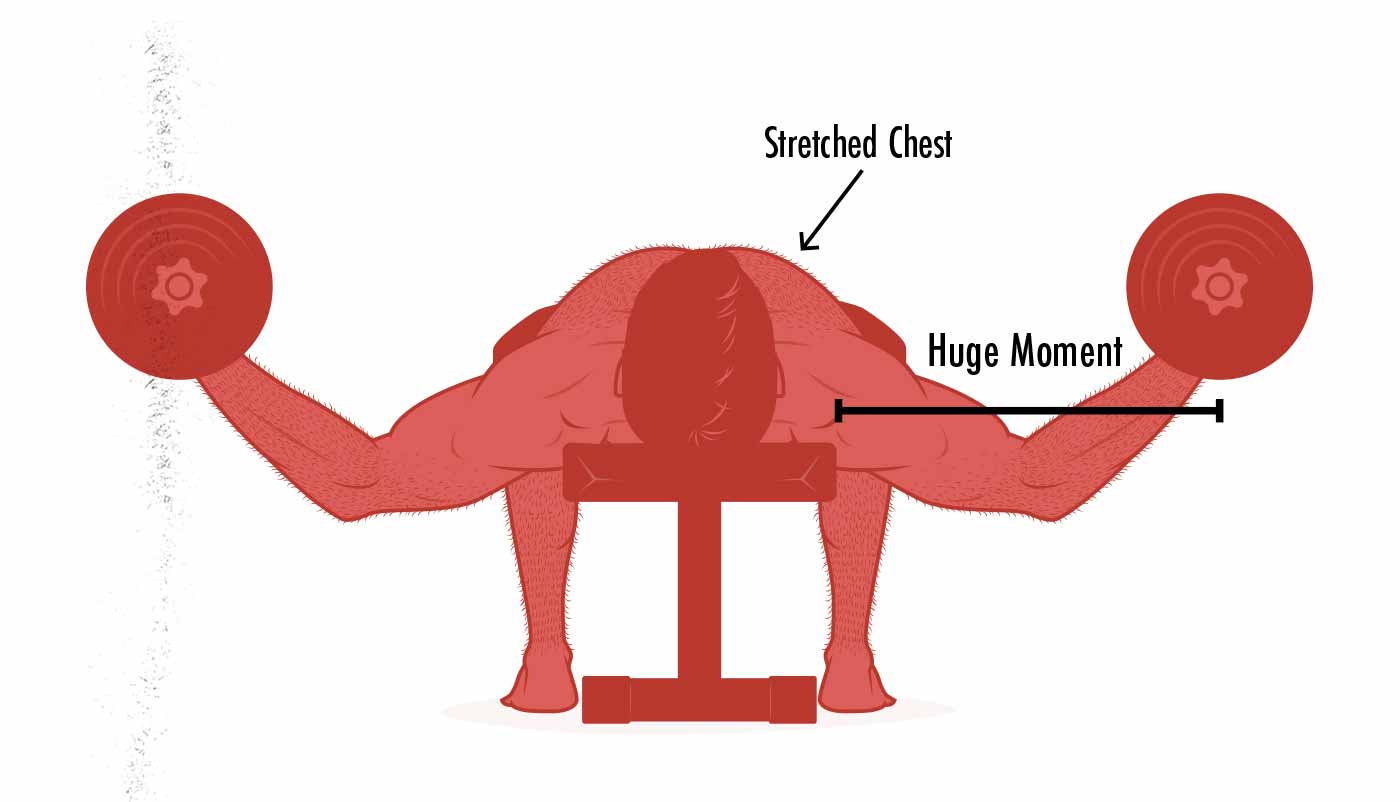

This tells us that the bottom position of a dumbbell fly (with your chest stretched) stimulates more muscle growth than holding the top position of a cable crossover (with your chest contracted).

Since then, dozens of other studies have come out showing that long-muscle-length training stimulates far more muscle growth than short-muscle-length training. More controversially, it often stimulates slightly more muscle growth than training through a full range of motion.

So, let’s talk about how to train your muscles at long muscle lengths.

Introduction

The Stretch-Mediated Hypertrophy Myth

There are brutal studies where researchers stimulate muscle growth by hanging heavy weights from pigeon wings for weeks at a time, keeping them under a heavy stretch. That muscle growth is called stretch-mediated hypertrophy.

More recently, researchers had people lock their lower legs into painful devices that maximally stretched their calves for an hour per day (study). Again, there was muscle growth, but not very much—about as much muscle growth as you’d get from doing fifteen minutes of conventional calf raises.

Long-muscle-length training (challenging your muscles through a deep range of motion) isn’t the same as stretch-mediated hypertrophy (hypertrophy from stretching). They probably don’t have much to do with each other. And that’s good. Long-muscle-length training is far more powerful.

However, when long-muscle-length training first started becoming popular, it didn’t have a name, and it was often grouped in with stretch-mediated hypertrophy (in the mainstream and also in the research). As a result, the two terms have become somewhat intertwined. To be as clear as possible, we’re going to call it long-muscle-length training.

The Groundbreaking Study

The study that opened the floodgates was this systematic review: Isometric Training and Long-Term Adaptations: Effects of Muscle Length, Intensity, and Intent. It showed that challenging our muscles at long muscle lengths could double or even triple muscle growth.

The first thing to note is that this is a review of isometric lifts. An isometric lift has zero range of motion. Think of how a plank trains our abs or how a deadlift trains our spinal erectors.

The researchers used isometrics because holding weights at different parts of the range of motion makes it easy to see which parts are best at stimulating muscle growth. It also removes the skill component of the exercises.

This study proved John Parillo and Dante Trudel’s “extreme stretching” concept, giving it a second wave of popularity via evidence-based bodybuilders like Jeff Nippard. It gets much more interesting.

Supporting Research

Once the principle was proven with isometrics, researchers started studying traditional bodybuilding and strength training exercises.

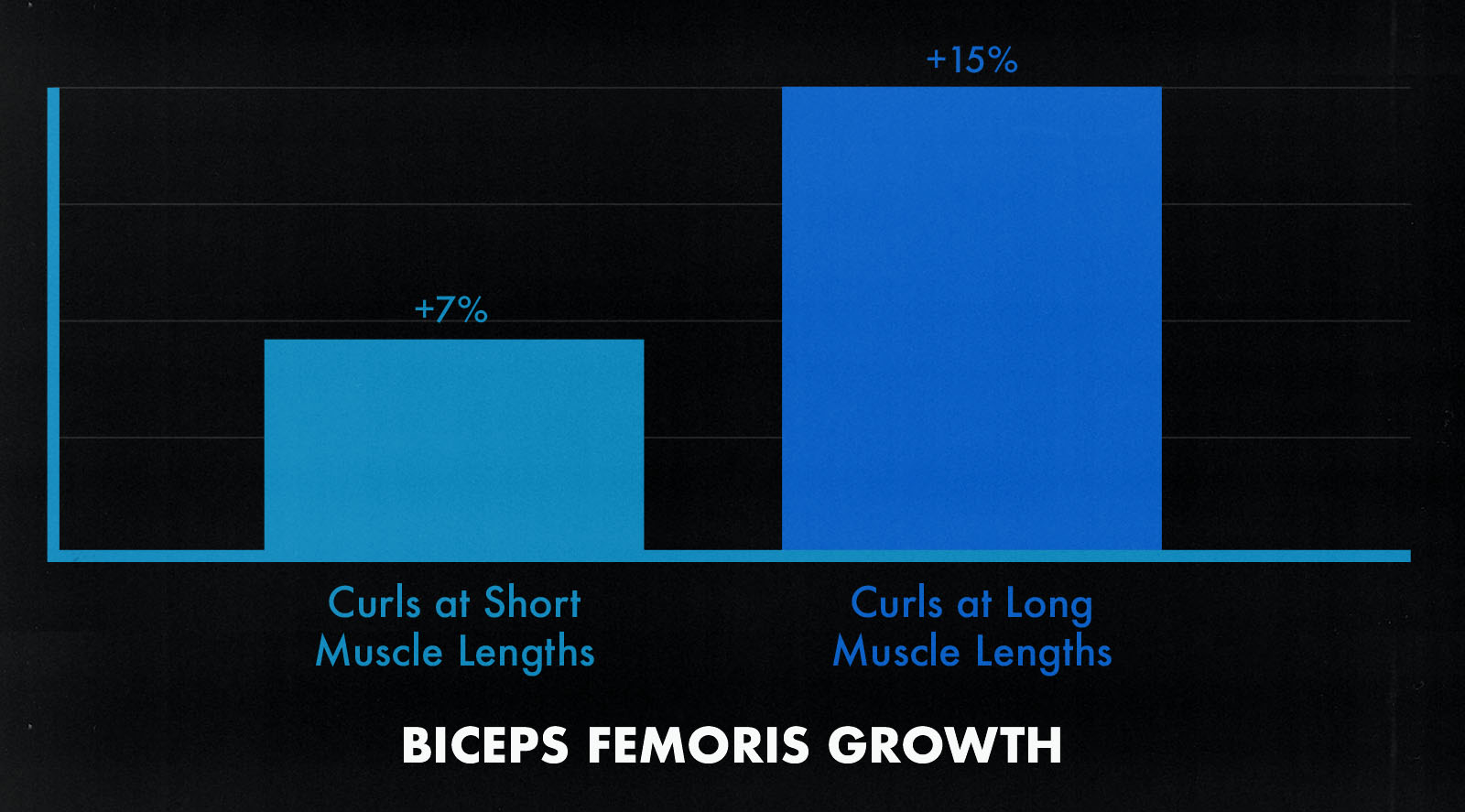

For example, a study by Maeo and colleagues compared seated hamstring curls against lying hamstring curls. The range of motion at the knee joint was the same in both exercises, but some of the hamstring muscles cross the hip joint, stretching out when we bend at the hips. That extra depth at the hip joint more than doubled muscle growth.

What’s neat is that the different muscles in your hamstrings are stretched to different degrees when you bend at the hips. The areas that got the greatest stretch (such as the biceps femoris) saw the greatest growth. The areas that were unaffected didn’t see any difference in muscle growth.

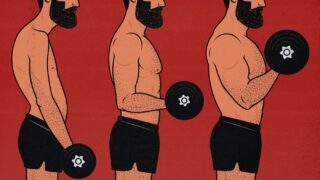

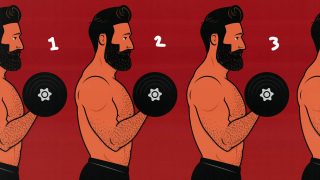

This is just one of many studies. In 2024, Maeo published a follow-up paper showing double the muscle growth from training your hamstrings at longer muscle lengths (study). Kubo found that deeper squats stimulate more muscle growth than shallower squats (study). For another popular example, Sato found that doing just the bottom half of a biceps preacher curl stimulated almost three times as much muscle growth as doing just the top half (study).*

*Doing just the bottom part of the range of motion is called a lengthened partial (full article).

Why Does Depth Affect Muscle Growth?

We now have dozens of studies showing that challenging our muscles at longer muscle lengths yields the greatest amount of muscle growth. But why is that? The nuanced answer is that we don’t know yet. The mechanisms are still being studied. The best we can do is guess.

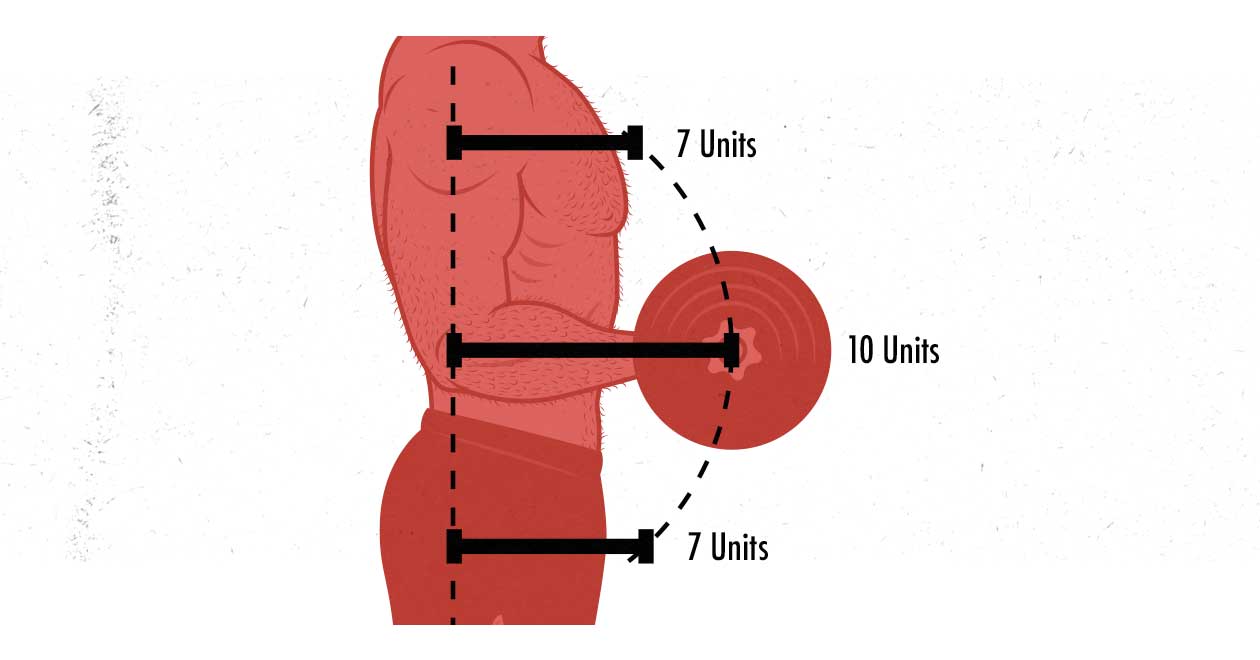

One popular explanation is that the more tension we put on our muscles, the more muscle growth we stimulate. It could be that training at long muscle lengths is a way of increasing total tension. This example is simplified, but if you follow where it leads, you wind up with extra growth.

Another possible explanation is that training at long muscle lengths does a better job of stimulating the distal portions of our muscle fibres. The extra growth comes from those distal portions, helping us build longer, fuller muscles. This is validated by almost every study so far. This doesn’t rule out the extra growth coming from extra tension. It may just be that the extra tension on those distal portions is helping them grow.

Either way, I think it helps to understand a few principles.

The Sticking Point

If one part of the range of motion is especially hard, creating a sticking point, then that’s the point where our muscles contract the hardest, producing the most mechanical tension.

On most lifts, the hardest part is when the limb that serves as the lever is horizontal, creating a longer moment arm. For some examples, the hardest part of a barbell curl is when our forearms are horizontal, the hardest part of a bench press is when our upper arms are horizontal, and the hardest part of a squat is when our thighs are horizontal. That’s where the weight is the heaviest on our muscles, where our muscles need to contract the most forcefully, and where mechanical tension is the highest. This is where most of our muscle growth comes from.

Resting Length

The next thing to consider is that our muscles can produce the most contractile force at their resting length—the length of your muscles when you’re standing in a relaxed position. So if the sticking point of the lift is around that point, you’re stronger, able to lift more weight, and able to generate more mechanical tension. That’s great for building muscle.

If we consider the bench press, the sticking point is when our upper arms are horizontal, which puts our pecs at resting length, where they’re able to generate the most contractile force. That’s great. That’s a great strength curve for building muscle.

Passive Tension

Passive tension might also play a role, maybe. As we’ve just covered, the main way that we produce force with our muscles is by actively contracting them, producing active tension. But our muscles also behave somewhat like elastics. When you stretch them, they pull themselves back toward their resting length.

This extra tension is called passive tension, and it means you’re also quite strong when your muscles are stretched. When you combine active tension with passive tension, you have more overall mechanical tension on your muscles, stimulating more muscle growth.

Greg Nuckols, MA, did a good job of explaining the mechanistic evidence in Monthly Applications in Strength Sport:

“While active contractile tension of a muscle tends to be highest at around resting length, passive tension from non-contractile elements (the tendons and muscle fascia) increases as muscle length increases, such that total muscular tension is generally highest when muscles are in a stretched position. Tension primarily seems to matter for hypertrophy because tension is sensed at costameres (where muscles attach to the surrounding fascia), which activate a protein called focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which then triggers the mTOR pathway, which is primarily responsible for exercise-induced hypertrophic signaling. In exquisitely controlled rodent research (study), it’s been shown that tension itself, not just active tension generated by muscle contraction, is what kicks off this pathway. Thus, even though active tension drops off, the disproportionate increase in passive tension, which leads to more total tension, should also lead to more hypertrophic signaling.”

Examples

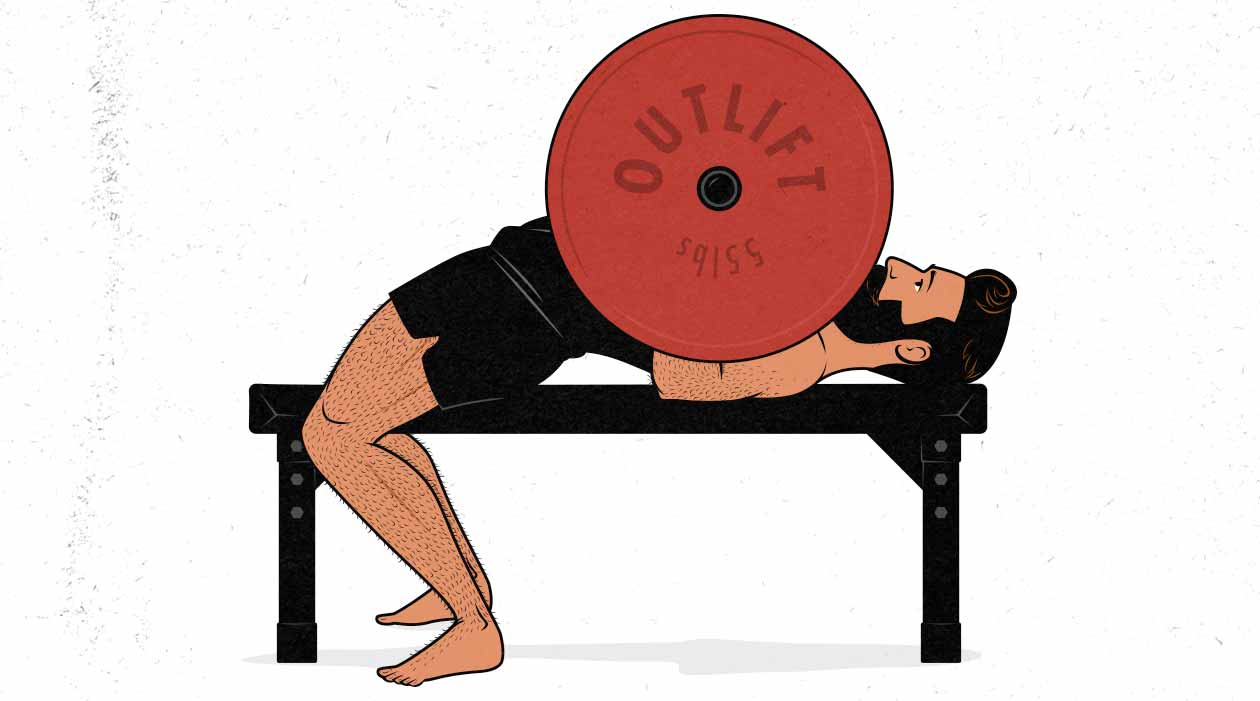

If you fully stretch your chest out at the bottom of a dumbbell chest fly (maximum muscle length), and that also happens to be your sticking point (maximum tension), then you should expect to stimulate a maximal amount of muscle growth.

If you used cables to make the exercise harder when your chest was contracted, you’d expect that to give you a greater pump/burn but also to stimulate less muscle growth. Thus, in this case, the dumbbell fly should be the better muscle-building exercise.

For another example, if you’re doing resistance-band squats, say, then the load is light when your quads are stretched at the bottom and hard when your quads are contracted at the top. You’re getting a full stretch, but the stretch doesn’t overlap with the sticking point. You aren’t challenging your muscles at long muscle lengths. That’s why free weights and bodyweight exercises tend to be better than resistance bands for building muscle. Most exercise machines are pretty good, too.

That brings us to accommodating resistance. Accommodating resistance is where resistance bands or chains are added to barbell lifts to make them more challenging at the top of the range of motion. The bands and chains don’t make the bottom harder, just the top. Since most of our muscle growth comes from challenging our muscles at the bottom, it makes sense that making the top harder wouldn’t help very much, if at all.

Which Lifts Challenge Our Muscles at Long Muscle Lengths?

The Big Three Lifts

Most popular exercises are pretty good at challenging your muscles at long muscle lengths. I suspect that’s why they became popular in the first place: they work better.

- Squats challenge your quads in a stretched position, especially if you “sit down” into a deep squat instead of “sitting back” into a parallel squat. This benefit is even more exaggerated if we do front-loaded squats with a lot of bend at the knees, such as deep front squats.

- The bench press challenges your chest and front delts at relatively long muscle lengths. Variations like dips and deficit push-ups can get you an even deeper stretch.

- Deadlifts challenge your hips, hamstrings, and traps at long muscle lengths. Deadlift alternatives can be just as good. For example, Romanian deadlifts do a better job of loading your hamstrings under a maximal stretch.

You can fiddle with the big three a little bit, but they have great strength curves for building muscle.

The Big Five Exercises

The Big Three are well and good for powerlifting, but we usually recommend the “Big Five Exercises” when training for muscle size, general strength, and aesthetics. By switching from back squats to front squats, and then adding chin-ups and overhead presses as main lifts, we gain much more upper-body size and strength.

If you add chin-ups as a foundational lift, you have a main lift for your lats, upper back, and biceps. By adding in the overhead press, you have a lift dedicated to building bigger, stronger, and broader shoulders.

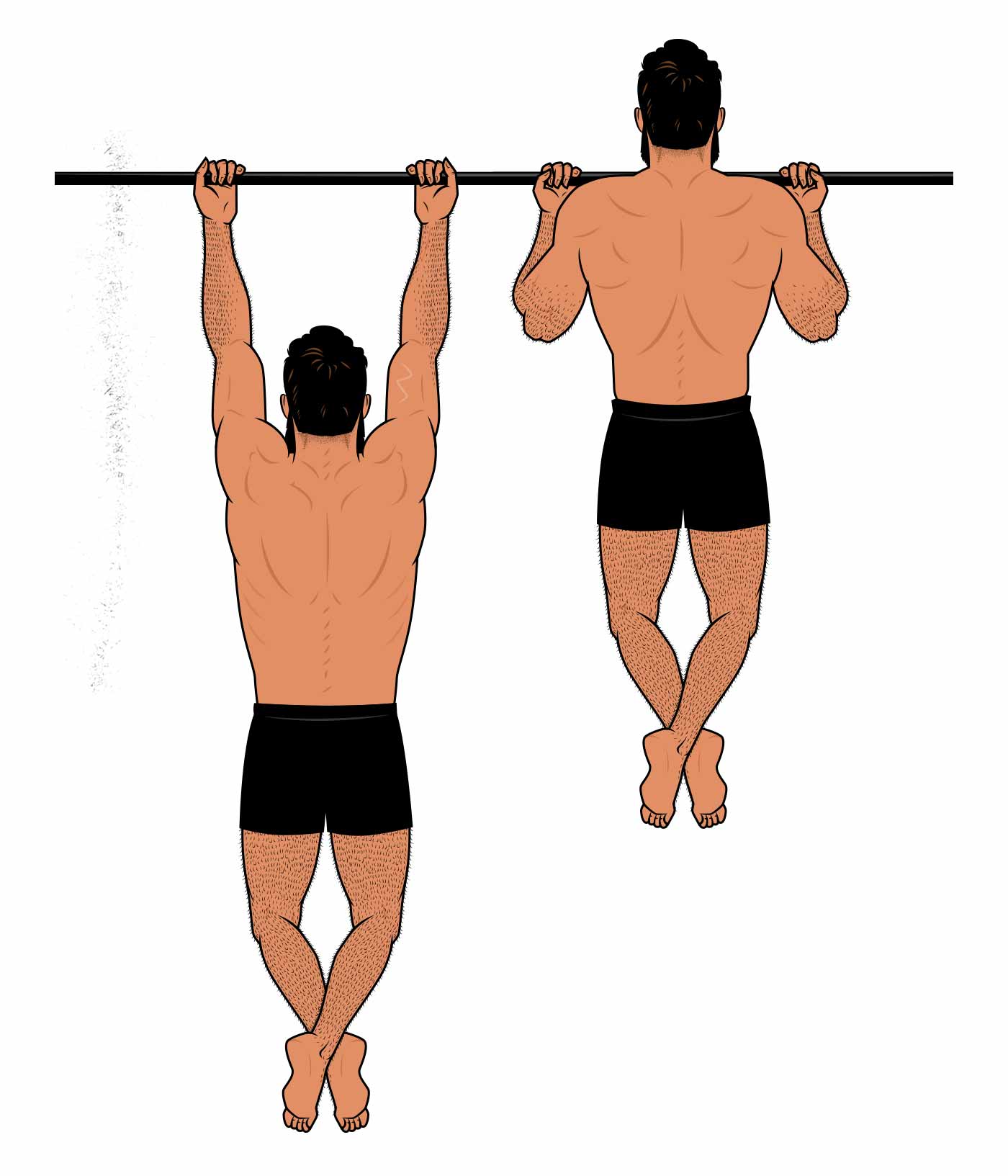

The Chin-Up

The chin-up has a reasonable strength curve. Any lift that challenges your lats (and teres major and rear delts) while your arms are in front of your body is challenging them at long muscle lengths, and the chin-up does that. It’s hardest on your lats in the middle of the range of motion, when your upper arms are still quite far in front of your torso.

Compare that against a barbell row, which is hardest at the very top of the range of motion, when your muscles are at much shorter lengths. Barbell rows have other advantages, but chin-ups and pull-ups are likely better for your lats, teres major, and rear delts.

Pullovers bring your arms fully overhead, stretching out your back muscles even more. In fact, they bring your arms so far overhead that your lats can’t fully contribute anymore. They’re fantastic for your teres major, though.

The Biceps Curl

For biceps growth, some research shows that preacher curls (harder at long muscle lengths) stimulate more muscle growth than cable curls/incline curls (harder at medium muscle lengths). Another study found that the bottom half of preacher curls stimulates more muscle growth than the top (study, study, study).

So, at first glance, the preacher curl seems perfect for building bigger biceps. The only problem is that when you bring your arms in front of your body, it shortens the long head of your biceps at the shoulder joint. You can address that by also doing lying biceps curls:

And, of course, you can always do regular biceps curls. Dumbbell curls and barbell curls are still great. You can make the bottom of the range of motion harder by “throwing the bar through the ceiling” (video tutorial).

The Overhead Press

My favourite trick for getting more muscle growth out of the overhead press is to explode out of the bottom. That way, you’re working your shoulders as hard as possible right from the get-go. But it’s not a perfect solution. You still aren’t training our shoulders in a fully lengthened position. You might need to make up for that by doing extra sets.

As I’ve tried to mention at every opportunity, that’s not the end of the world. It’s a big, heavy, compound exercise that stimulates a ton of overall muscle growth. Plus, your other pressing exercises will work your front delts at longer muscle lengths.

The Lateral Raise

The lateral raise starts at resting length and only gets challenging in a fully contracted position. That may explain why your side delts never get sore and grow rather slowly. You can fix that by using cables or lying on your side.

I didn’t expect these to work very well, but no other lift has worked my side delts as hard or made them as sore afterwards. Those aren’t perfect proxies of muscle growth, but they’re good signs.

The Triceps Extension

When you move your arms in front of your body, you lengthen your triceps at the shoulder joint. That means skull crushers challenge your triceps at longer muscle lengths than triceps pushdowns or kickbacks.

We can exaggerate the stretch even more with overhead extensions. Not everyone can do them comfortably, but if you can, they’re fantastic (video tutorial).

The Deficit Push-Up

Even regular push-ups are great for stimulating chest and shoulder growth, stimulating about the same amount of muscle growth as the bench press. But you can go even deeper by raising your hands up on handles, weight plates, or speculative fiction novels. These are called deficit push-ups.

Once you’re good at deficit push-ups, you can progress to dips, which train your chest under a maximal stretch. However, note that dips are a better for your lower chest than upper chest, so you might want to pair them with some incline pressing.

The Dumbbell Fly

The dumbbell fly is another great lift for challenging our chests while maximally stretched. The dumbbell fly is hardest at the part that stimulates the most growth (long muscle lengths) and easy at the part that stimulates the least growth (short muscle lengths). That’s why it’s such a great chest builder for guys with stubborn chests.

On the other hand, chest flyes are also redundant. If you’re already doing the bench press, and especially if you’re also doing deficit push-ups (or dips), then your chest is already being challenged in a stretched position by several different lifts (study).

The Problem (and Power) of Partial Reps

We miss out on muscle growth by cutting out the bottom of the range of motion, but there’s little harm in cutting out the top. In fact, if you don’t fully lock out your skull crushers or dumbbell flyes, you might even slightly increase muscle growth. These are called lengthened partials.

You can also choose lifts that use a full range of motion but that emphasize the stretch, such as:

- Wide-grip deadlifts instead of rack pulls

- Front squats instead of half squats

- Deficit push-ups instead of diamond push-ups

- Incline curls instead of spider curls

Summary

You can build more muscle by lifting with a deep range of motion, challenging your muscles at long muscle lengths, and not stressing too much about getting a full contraction. Most exercises are already great for that: deep squats, bench presses, dips, Romanian deadlifts, and overhead extensions.

Other lifts emphasize the contracted part of the lift and thus tend to be less good for building muscle: spider curls, hip thrusts, glute bridges, half squats, above-the-knee rack pulls, floor presses, cable crossovers, and resistance-band exercises.

Finally, we can improve the growth stimulus of some lifts by extending the range of motion and/or making them harder at the bottom of the range of motion: deficit push-ups, preacher curls, lying biceps curls, lounging lateral raises, seated hamstring curls, and standing calf raises.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you’re eager to gain your first 20–30 pounds of muscle, check out our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. We’ll walk you through the entire process. If you’re an intermediate lifter, check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. All of our programs build these principles into the workouts.

What about using cables for lateral raise? A cable coming from the low side will be more challenging when the lateral deltoid is stretched and will be easier when it is contracted.

Yeah, totally! That gives the lateral raise a much better strength curve 🙂

This article specifically points out rack pulls as an inferior movement because of how it emphasises the wrong part of the range of motion — the top. What’s the reasoning behind using rack pulls and raised deadlifts in Phases 1&2 in the main b2B program?

Hey Joe, that’s a good question.

I’m pointing out the flaws of above-the-knee rack pulls here, which are the more common type of rack pulls that are used by intermediate and advanced lifters. In the Bony to Beastly Program, we use below-the-knee rack pulls. It’s sort of a Romanian deadlift but done from a dead stop. There’s full range of motion for the hips there, just a bit less movement at the knees, less involvement from the quads. So there isn’t really a range of motion issue there. It also makes the lift a bit simpler to learn, helping beginners transition to doing deadlifts from the floor.

The other thing is that the main downside to rack pulls is that they generate a lot of fatigue for the benefit you get. That can become a real problem as you get stronger. But for a beginner, it doesn’t really matter. If a beginner is doing 3 full-body workouts per week, they aren’t strong enough or training rigorously enough to run into those problems. They’re more likely to run into problems with a sore and fatigued lower back, and below-the-knee rack pulls aren’t too bad for that.

Plus, we also use Romanian deadlifts. So even then, we’re mixing in a less fatiguing lift with a deep stretch and a full range of motion.

The same idea is true with raised deadlifts. Very similar to below-the-knee rack pulls.

Finally, after those initial b2B phases, we transition to deadlifts and never look back. We don’t really use rack pulls anywhere else after that.

Thanks for the detailed response, Shane 🙂

I had figured it was only to do with helping to transition to deadlifting from the floor, as you said. However the other aspects you describe have made me realise that I’ve been doing my rack pulls in phase 1 from too high of a start position — not above the knee, but very much at the knee.

I know I should be asking this on the B2B forums (I haven’t gotten round to making a progress thread yet — I’ll get to it!) but do you have any recommendations for my transition to full deadlifts? I almost feel like I’m behind in my progression– the program is asking for:

(below the knee) rack pulls –> raised deadlifts –> deadlifts.

Whereas having started at the knee I wonder if I shouldn’t go:

rack pulls at the knee –> rack pulls below the knee –> raised deadlifts –> deadlifts

but then I’ll be a phase behind. Do you think it’s worth it or should I just start doing raised deadlifts in phase 2, ignoring that it’s a bit more of a jump in terms of the range of motion?

You could do some Romanian deadlifts, see how deep the barbell goes at the bottom of the lift, when your hips and hamstrings are fully stretched, and then set up raised deadlifts or rack pulls from that position. Do that until it feels natural, and then drop down to the floor the next phase, adding in the knee bend to turn it into a full deadlift. The main thing is just to make sure that you’re deadlifting with a fairly neutral spine, that your brace is feeling good, and that the movement is coming from the hips. Once that feels natural, you should be able to deadlift from the floor without issue. And, I mean, some beginners can deadlift from the floor when first learning the movement. It’s not like these introduction steps are even mandatory. And the reverse can be true, too, where some people have a really hard time deadlifting from the floor. So you’ll have to play it by ear, seeing how it goes for you.

Don’t worry about falling behind. There’s no rush. All of the movements build muscle and strength 🙂

Hi Shane, thanks for a very interesting article.

Your variation on the lateral raise works my shoulders very well for me. I was wondering how much it works your rear delts relative to your lateral delts, since the end of the motion seems to resemble a face pull? I’m unsure as to whether this might interrupt rear delt recovery if I’ve trained them hard the day before. And would bending your arm more shift the emphasis at all (my ‘bench’ is lower than yours)?

Re triceps, I understand that overhead extensions are ideal for stretching the long heads – but what about challenging the medial and lateral heads in a stretch? I have shoulder impingement and my elbows are prone to flare up, so I’m stuck with cables. Would pushdowns be a good choice, or would it be better to start with my elbows pushed back and turn it into more of a kickback movement?

Many thanks,

Marcus

I’m glad that the weird lateral raises are working for you! They hit my side delts so hard, and it’s such a stubborn muscle for me, but I wasn’t sure how well it work for other people.

Bending your arms will shorten the lever, allowing you to lift more weight or get more reps. Should still work the same muscles to the same degree, though.

This exercise might work the rear delts, yeah. You’ll have to see how sore they get. For me, that wasn’t the case, but it’s certainly possible.

All triceps isolation exercises involve bending the elbows, which stretches the triceps. You’ll get a maximal stretch on the long head with an overhead position, but all triceps exercise will stretch your triceps. Don’t worry about that. Choose the exercise that feels best on your elbows and shoulders.

Cheers

So deadlift, once mastered, is a superior movement to romanian deadlift in terms of hamstring development or just as an overall mover, because you can move more weight with DL and have a deep stretch on more involved muscles?

I mean, if you could do only one (maybe alternate weekly DL and RDL), which would you do?

Its a bit hard to fit both movements in 3 x week full body routine.

I get very sore hams with RDL’s, with DL ‘s I get sore lower back, lats (if correctly presqueezed), upper back.

Hey Denzel, that’s a good question.

So, the thing with the conventional deadlift is that you typically bend a fair bit at the knees, which releases some slack from the hamstrings. Not a big deal, but it’s the Romanian deadlift where you get the slightly greater strength on your hamstrings. I’d say the Romanian deadlift is a better hamstring lift, but both are great.

I think it’s nice to have both in a workout routine, at least at some points in your training. Maybe spend some months training the deadlift, some months training the Romanian deadlift. When you’re focusing on a given lift, try to make progress, try to get stronger. And then when you switch to the other, it should be enough to at least maintain your strength. The two are very similar, all things considered (especially if you’re doing them for hypertrophy, with a slower lower).

Your side lying lateral raise is a great exercise that I’m surprised isn’t more common. Even if we didn’t know about the specific benefits of training muscles at long muscle lengths, at the very least it offers a different strength curve than the traditional lateral raise.

With that being said, thanks to that I’ve also started implementing a side lying rear delt version where I fly the weight out but in a reverse fly motion. Not only does it give a huge ROM and a decent stretch at the bottom, but it also minimizes the work the mid/lower traps can do in the movement too.

Hey Kunmi, I love that idea of a lying rear-delt raise! That sounds awesome 🙂

Hi Shane,

What would you think of your lying lateral raise version being done with a 45 degree incline on the bench?

This seems to gravitationally line up with the angle of stretch for the side delt (https://exrx.net/Stretches/DeltoidLateral/SideDelt) whereas the one you demonstrated seems to be better for a rear delt stretch (https://exrx.net/Stretches/DeltoidPosterior/RearDelt).

That sounds great to me. I’ve tried it, and I like it. Give it a try and see how you like it. If it feels better, go for it.

It has been suspected from other previous articles related to this topic.

I’m surprised though, that no die hard band supporters came out to tell others that ” I built more muscle than ever once I started training with bands”. We’ve all heard them ( Not ‘seen’ them for our surprise).

Band training has its merits for sure but mass building isn’t one of them as this article and the article this article referranced about how muscle builds a lot more efficiently when it’s stressed at stretched positions.

It’s because the band supporters are commenting on our article about resistance bands. I enjoy when people disagree, and I like that some people seem to get good results from using bands. I agree with you, though. I don’t think resistance bands are ideal for gaining size or strength. Not awful, but not ideal, either.

Hey, I was curious about what evidence you’re using for your claims about isometrics being poor for hypertrophy. I have been exploring isometrics at long muscle lengths and have had mixed results, but my confidence about investing more time into them wavers with all the mixed info on them. The company behind a product I use, the Dragon Door Isochain, claims dynamics and isos are roughly equivalent for muscle growth, but they’re clearly somewhat biased.

Do you have any info on exactly how much worse they are compared to dynamic exercises for hypertrophy?

There seems to be a fair amount of conflicting info on the web about this, but Isometrics are very niche and I wonder why.

Many thanks

Hey Prospero, that’s a really good question. All of the top hypertrophy researchers recommend lifting through a deep range of motion to stimulate muscle growth instead of doing static holds. That includes researchers like Dr. Brad Schoenfeld. All the top natural bodybuilders and strength athletes over the past hundred years have included plenty of lifts done through a deep range of motion as well. You’re right that isometrics are fairly niche, and there may be good reason for that. However, I wonder if isometrics done in a lengthened position rival exercises done through a deep range of motion. I can take a look into this.

At the moment, if it were me, I’d use a mix of approaches. I’d add the lengthened isometrics to a more traditional hypertrophy training routine. Also keep in mind that most hypertrophy training routines already include a good bit of isometric work. Think of how push-ups and chin-ups train the abs, deadlifts train the spinal erectors and back, and so on. Most guys with big traps and spinal erectors got them from doing deadlifts, training them isometrically.

At the moment, I’m most excited by deep partials. I think that’s the most promising “new” muscle-building technique. The research is fast becoming overwhelming, and it also has a long tradition in the bodybuilding community. Many top bodybuilders have avoided locking out their exercises, staying in the deeper part of the range of motion. And even with lengthened partials, I’d incorporate it into a more traditional hypertrophy routine.

Really good question. Thank you for asking it.

I see. Yeah, partial reps in the ‘stretch/deep/lengthened’ range (quite a few names for it apparently) seem like they could be more efficient than full RoM for hypertrophy, but I barely know what I’m talking about. The isochain has been interesting and confusing. With it, I’ve put on about 20lbs of mass in 1.5 years, of which roughly 11 is muscle if my scale is to be believed. Mostly been doing 6 sets of 6 second holds (strength), 3 sets of 20 seconds and 2 sets of 45-60 second holds (hypertrophy) in the lengthened positions. Another even more obscure device that I’d be curious about opinions on is the Isokinator, which is technically dynamic, but whose movements seem borderline alien. It has worked for me, to an extent, but it suffers from ergonomic issues (it uses straps) and the leg exercises are wonky.

Hi Shane,

Great website. I’ve been studying several of your write-ups, specifically the ones regarding stretch-mediated hypertrophy and strength curves. I’ve been using a popular elastic band training system that utilizes a bar and ground plate for just over 2 years. I travel quite a bit so the band system is easy to carry with me and helps me to be consistent with my training. I have made good progress but have plateaued on several movements. I recently turned 65 and have worked out most of my life and am always looking for an edge.

Recently, based on the studies you have mentioned and your descriptions, I have added movements that incorporate loading muscles in stretched positions mostly using bands to the standard band program movements. Example: Added standing banded preacher curls (with close grip on the bar and elbows supported on my lower rib cage and abs) to the banded drag curl.

Instead of doing full reps followed by partial reps to full fatigue on the regular banded drag curl, I do as many full reps as I can (around 20 for current bands on the drag curl) then immediately move to the preacher curl. I max out around 10 partial reps (from elbows nearly straight to the point where band force is just past perpendicular to my forearms, which turns out to be a pretty strong sticking point with the band I’m using).

My thinking is that I can benefit from both loading the biceps near full contraction with the drag curls and then in stretch with the preacher curls. This is essentially using 2 partial ROM movements: Initial and final phases of two different bicep curl movements.

I have added other exercises to improve the chest press (added banded deficit pushups), overhead press (added stretch-mediated banded lateral raise), tricep press (added dumbell overhead tricep press), calf raise (added heel-drop single-leg calf raise), bent row (added full-hang pull-up) and split squat (added deep bodyweight single-leg eccentric squat and deep bodyweight sumo squat).

I added the above squat “finishers” several months ago and increased the number of banded split squats I can do from 15 to 26 full reps with the heaviest band I have after having plateaued at 15 reps for several months before adding them. I have also noticed increased hypertrophy in the area of my quads closer to my knees, much like the researchers had found. I didn’t know about loading muscles in stretch but after becoming aware of and studying it, I now attribute the gains to that.

I have also added reps on many of the other standard band exercises after incorporating the stretch-mediated movements just a couple of weeks ago. I have noticed that my chest and shoulders are becoming fuller (shirts are fitting tighter) so it seems that I am making progress there, too.

Thanks again for your very useful information.

Jim B

Hey Jim, that sounds great! That’s exactly what I would do if I were using bands. It sounds like you’re doing a great job of taking advantage of their strengths while minimising their weaknesses.

I’m not sure if there’s a benefit to doing variations that emphasise the contraction (like drag curls). So far, all of the research looking at exercises like that have found less muscle growth than when training at longer muscle lengths. It could be that training at both long and short lengths has some sort of advantage, but nobody has been able to find that advantage yet. On the other hand, there’s little harm in it. Plus, many classic bodybuilders built great physiques by choosing some exercises that emphasise the contraction.

Sounds like it’s working, too! That’s awesome how your chest and shoulders are becoming fuller, filling out your shirts. That’s always a great sign.

Also, I love how you’re 65, with a lifetime of lifting under your belt, and you’re still making progress. You’re killing it 🙂

Hi Shane,

Thanks for your reply. I’m starting with the movements recommended by the system’s workout instructions for the contracted exercise then adding a stretched version. Kind of a way to build on their basic method. That’s where the drag curl comes from.

I’ve tried more of a standard barbell curl with bands but didn’t seem to find any benefit. It’s a bit difficult to tune the resistance with the bands compared to small-increment dumbbells. So it’s been easier to use the drag curl.

If you have some other bicep movement that I can do with bands, I will certainly study them.

Thanks for the kind words. Like I jokingly tell my friends, “My plan is to live forever or die trying.”

Hah! That’s a great plan!

You could try setting up the resistance band behind you, doing a sort of banded Bayesian curl. That way, you’re stretching your biceps at the shoulder joint. You’d want to make sure you have plenty of tension at the beginning of the range of motion. It’s okay if you can’t bring it through the entire range of motion. No need for a full contraction at the top.

And then you already have the banded preacher curl. Those can complement Bayesian curls well. The long head of the biceps isn’t stretched at the shoulder joint, but you already have the Bayesian curl for that, so no worries.

That makes a lot of sense. Ok, the Bayesian curl is now on my pull-day workout ticket.

I’ll give it a go starting tomorrow.

Thanks again.

My pleasure, Jim! Good luck!

Been doing that in the early 2000 with really good results. I’ve read a lot of books and a friend of mine dig that in some books/sites he got a held on (I don’t know how he could get those info at that time,but I’m/was grateful for those info).

Let’s say I was doing bench press set 6-8 reps, after a set I took 5kg dumbbells and hold them for 20-30 seconds at the deep stretch pec dec fly position and then rest for another 2-3 minutes.

I think I’m gonna deep dive on some old info and try to find a connection between isometric contraction,CNS and muscle force as info about muscle force appears to be a good start:

A muscle cell develops maximal force when its length before the start of contraction equals 1.2-

times the value of its length at rest. This is the optimal muscle cell length. Initially if

the length of the muscle cell is greater or lower than optimal, the force of contraction is lower.

If the start muscle cell length is 65% or 170% of optimal length , the stimulus does not cause any change in

tension. Since the force in muscle is the result of the interaction between actin and myosin filaments, there are

different tensions, at different initial lengths of muscle cells, as a result of changing the transverse

bridges in the area where myosin and actin filaments overlap. This number is the largest at optimal length; at 65% of optimal length, the Z line presses on the myosin filaments and prevents each

rising tension; at 170% of the optimal length there is no contact between myosin and

actin and contraction is not possible

Maybe we should focus on satellite cells. These are above white muscle fibres (type 2X) and are activated by genome Myogenin,which then make possibility that they transfer to muscle fibers. Myogenin also activates two polypeptides (IGF1 and 2),which are released by muscle tissue tearing,which is caused by eccentric exercises.

Could you comment on injury risk? I’ve tried doing some of the weirder moves to get a full range of motion on front and lateral raises with cables and getting into a deeper stretch in the bench press. In most cases it just bothers my joints. Am I missing out on too much if I skip going full/deep range of motion in some exercises that bother me?

In general, training at long muscle lengths shouldn’t increase your injury risk. It’s good to build strength and mobility through a deep range of motion. It should make you more robust.

But that doesn’t mean everyone should go as deep as possible. Sometimes, it takes time to build towards a deeper range of motion. Other times, your body just isn’t built for it. You’re wise to notice that it’s bothering your joints. You shouldn’t push through it. If you can’t find a way to do it in a way that feels good on your joints, then you shouldn’t go as deep—at least not yet.

I don’t think you’ll miss out on much muscle growth if you go as deep as you comfortably can.

“holding the bottom position of an exercise stimulates nearly three times as much muscle growth as holding the top position.”

Let’s say I do both. Hold the bottom as well as the top position on the lat pulldown. Will it stimulate more muscle growth than holding just the bottom position when the bar is furthest away from me?

I think the most important thing is to challenge your muscles at the bottom. If pausing there helps you do that, it might help, and it certainly doesn’t hurt. Pausing at the top might be good if it improves your performance and is probably fine so long as it doesn’t hurt your performance. So, you could imagine two different scenarios:

1. Squats. You go deep, getting a nice stretch, maybe a slight pause at the bottom, or maybe you come right back up. Pausing at the top means a little bit of rest, and maybe that helps you get an extra rep. That’s probably neutral or good. The same might be true with bench presses.

2. Rows. You reach out at the bottom, getting a nice stretch, and you explode the weight up. Pausing at the top is very hard, though, so you wouldn’t be able to get as many reps or use as much weight. It would harm your overall performance. I wouldn’t do it. The same might be true with pull-ups/pulldowns.

Yeah, your second point matches my personal experience. Pausing at the top of rows/pulldowns is hell and I am convinced that it hurts my overall performance. Same with cable chest flys. I don’t know why folks emphasize holding the top position of exercises. Even the instructions on the lat pulldown machine in the gym say hold the bar close to your chest for 1-2 seconds before bringing it back up.

Yeah, that’s right. I agree. If you’re doing a dumbbell or cable chest fly, you might want to pause at the bottom, but you wouldn’t want to pause at the top.

I think most people associate the challenge and the burn with muscle stimulation. You can get a great challenge and burn by holding that top position. It FEELS like it should improve muscle growth. That doesn’t seem to be true, at least with the state of the evidence right now, but it’s counterintuitive.

The instructions on the exercise machine might not be quite right for maximising muscle and strength gains. On the other hand, it might help a beginner learn proper technique. I’ve seen Marco use holds like that to teach beginners how to do pulling exercises properly. For example, he might have someone hold their chest agains the chin-up bar when teaching someone how to do chin-ups. That’s very similar to what the lat pulldown machine is recommending.

Gottcha commander.

I watched the video on eating more calories and it’s for sure one of your best works. Congratulations to the entire b2B team and everyone involved.

Thank you, man! Really glad you liked it.