Chin-Ups vs Barbell Rows for Back and Biceps Growth

There are two lifts that are generally considered ideal for building our upper backs and upper arms, and both by very different groups. People who are more interested in strength training and powerlifting will often favour the barbell row, whereas people who are more interested in bodybuilding and bodyweight training will often favour the chin-up.

In this article, we’ll compare the range of motion, biomechanics, and muscles worked by both the barbell row and the chin-up, explain the differences, and then go over which one is better for building muscle.

Now, to be clear, we can certainly use both lifts in our workout routines—and we probably should—but it’s interesting to see which back exercise is better for building muscle, and what their different pros and cons are. That way we know which one we should be investing more of our time and energy into.

The Chin-Up & the Barbell Row

The Barbell Row

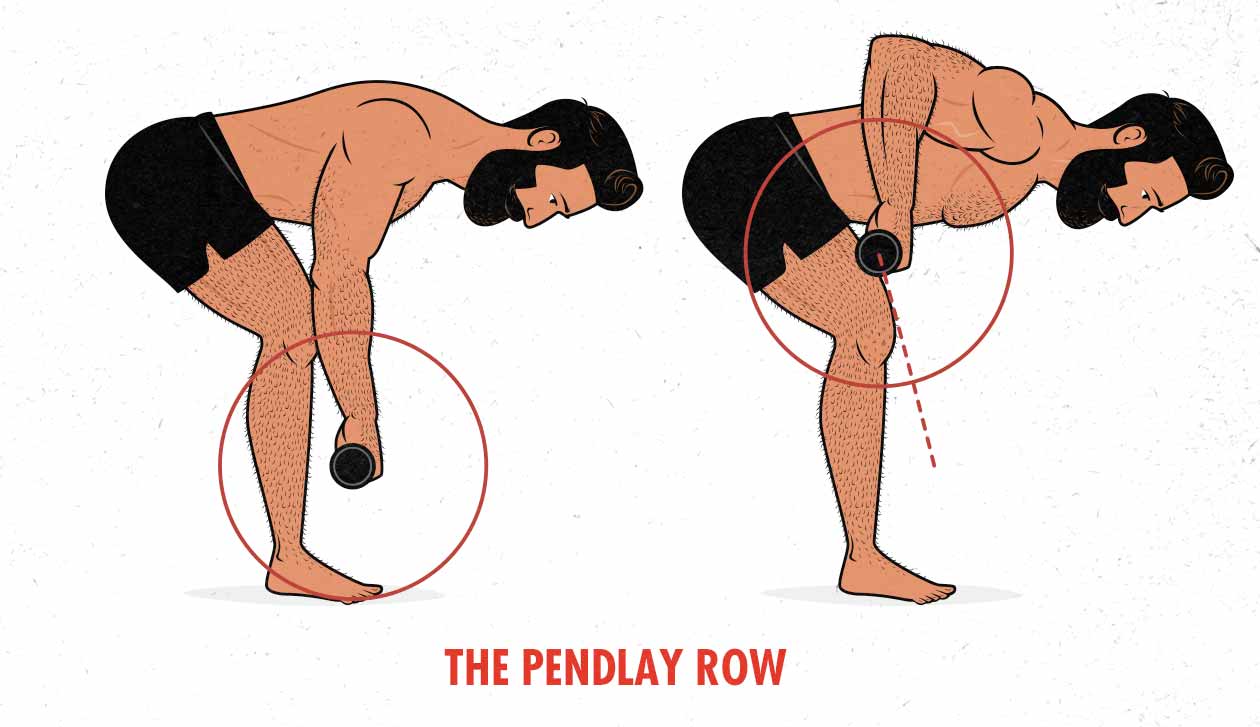

There are a few different ways of doing both chin-ups and rows, and you can certainly use any variation that you choose, but for the sake of this article, we can compare the two “best” versions of each: the chin-up and the Pendlay row.

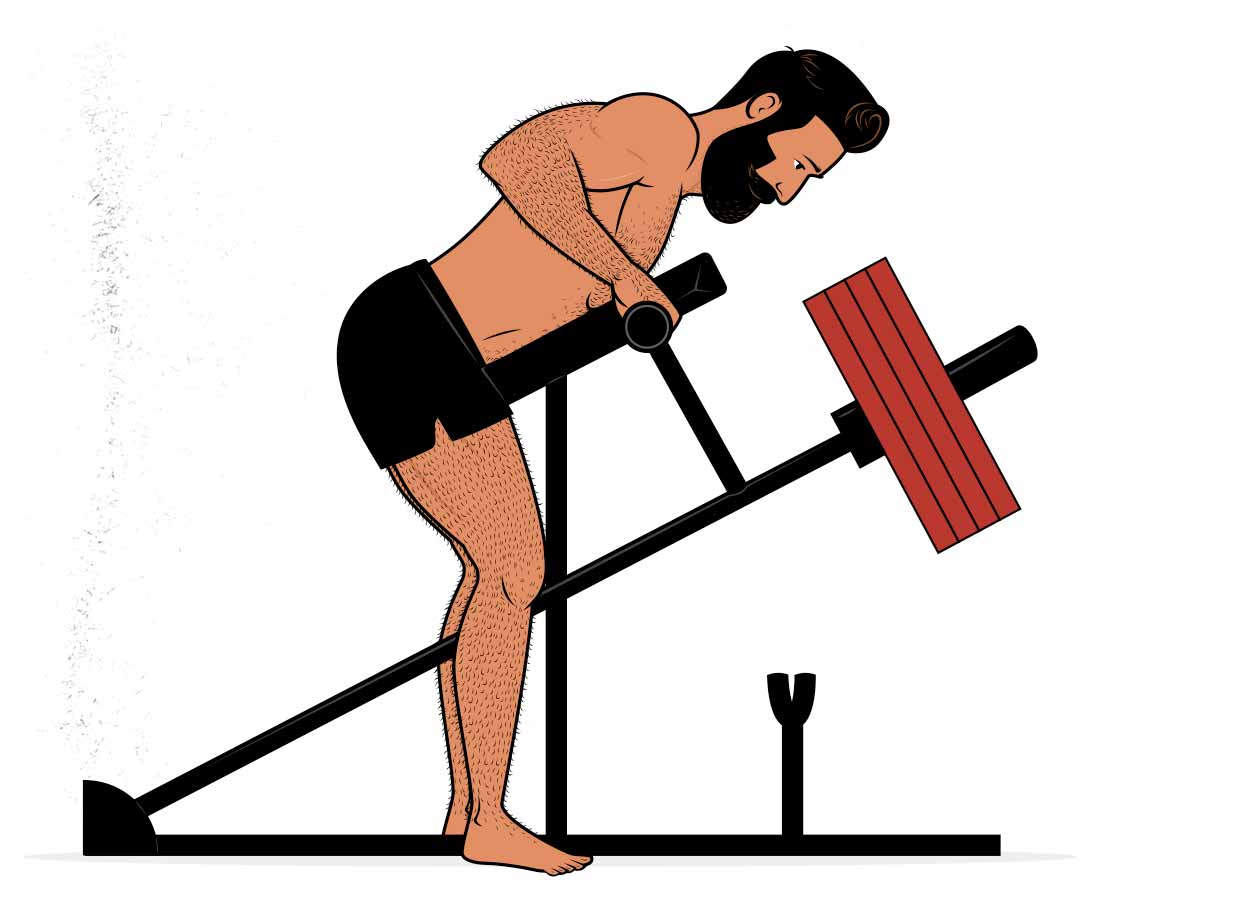

The Pendlay row has the barbell starting on the floor, we reach down to it by hinging at our hips, and then we row it up to our torsos without any hip drive. This row variation has the advantage (and disadvantage) of being incredibly demanding on our entire posterior chains, making it a good companion exercise to the deadlift.

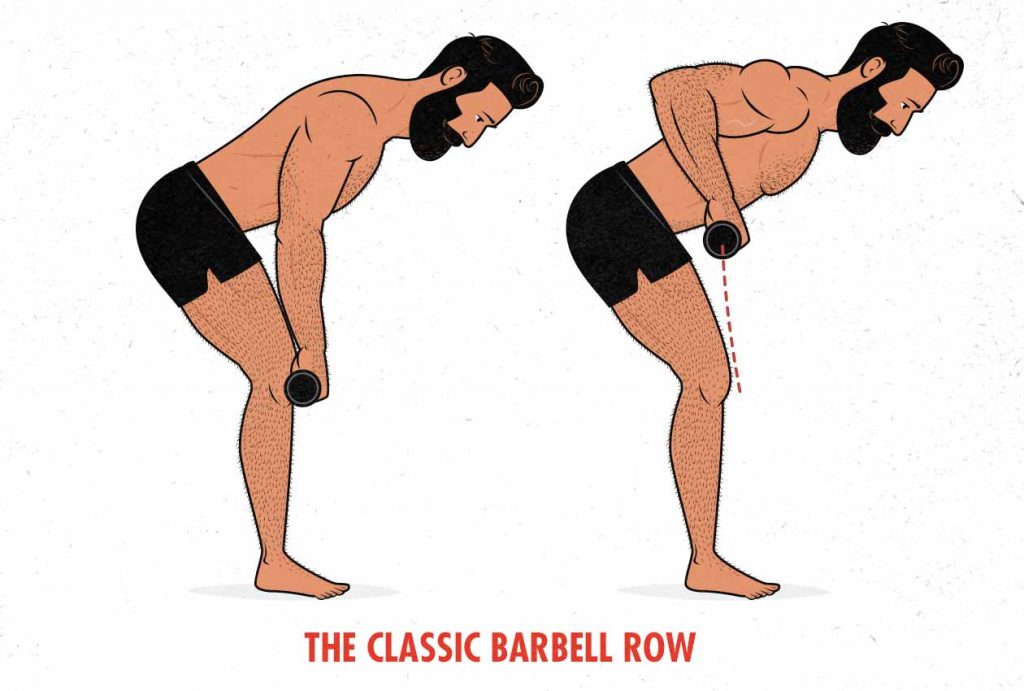

Another popular variation of the barbell row is what we call the “classic” barbell row, where we start in a Romanian deadlift position and then row the barbell from there. This variation is more popular with bodybuilders because it’s a bit easier on our lower backs, allowing us to focus on our upper backs. It’s still quite demanding on our lower backs, though, which brings us to the third variation:

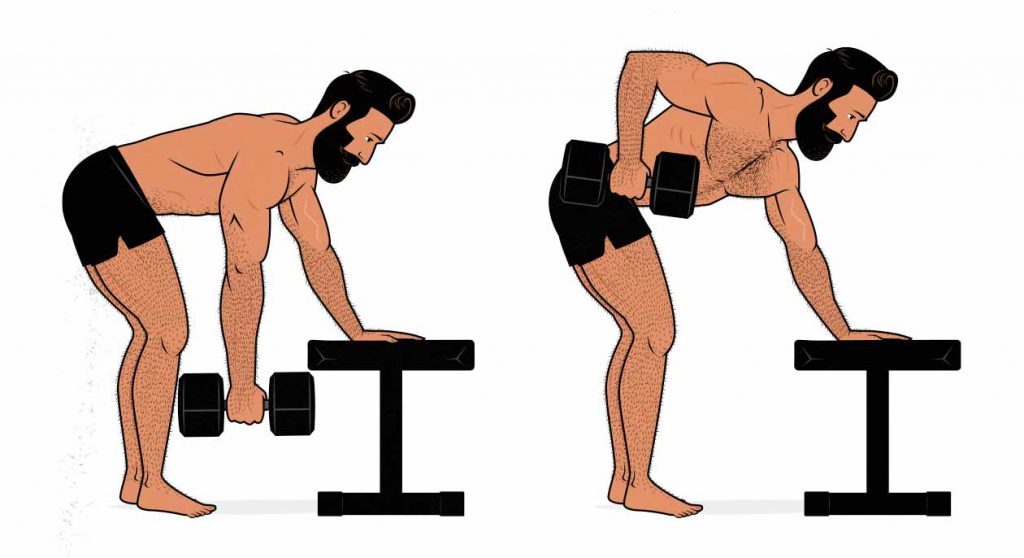

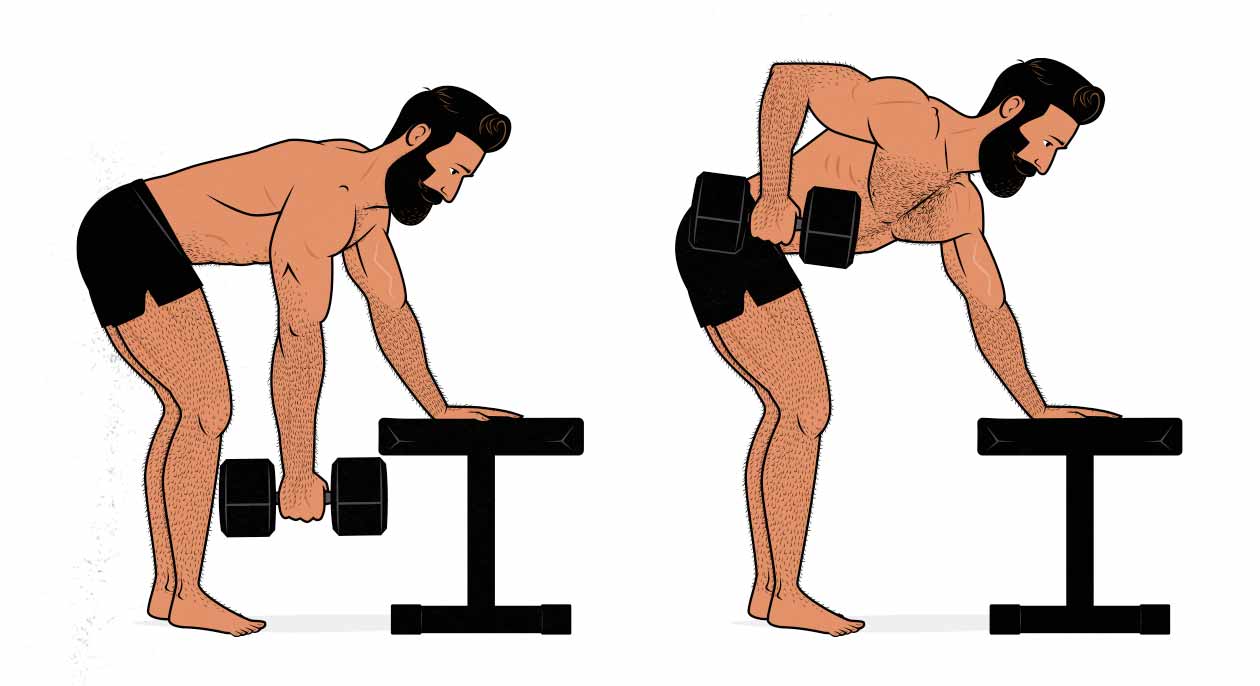

The dumbbell row has us supporting our torsos with one arm, meaning that we need to train both sides independently, but allowing us to take our lower backs out of the lift entirely. Plus, the dumbbell row lets us get a stretch at the bottom and then bring the dumbbell up past our torsos, giving it a larger range of motion. However, this is a lighter row variation that’s more of an accessory lift for our upper backs rather than being our main back exercise.

The Chin-Up

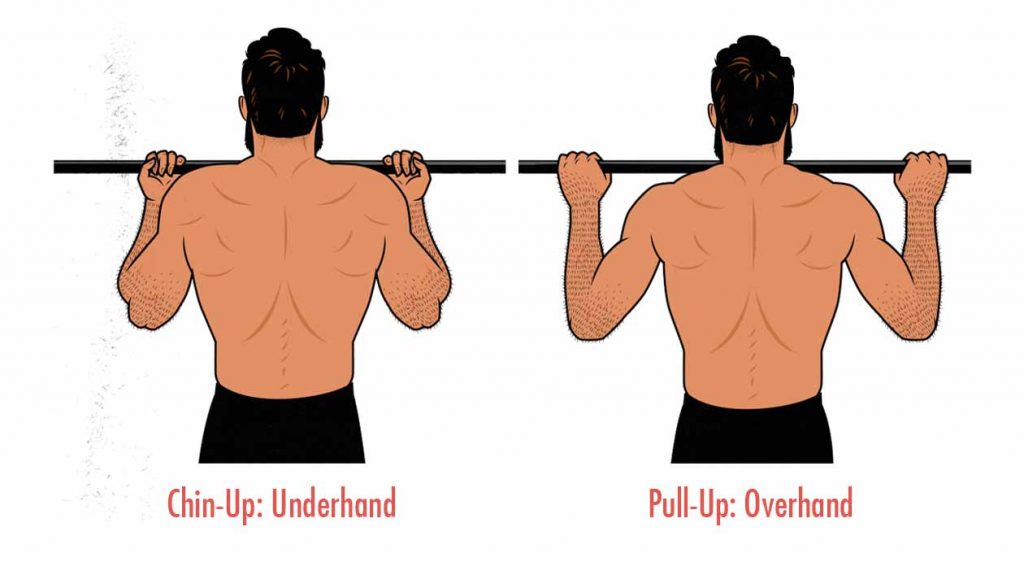

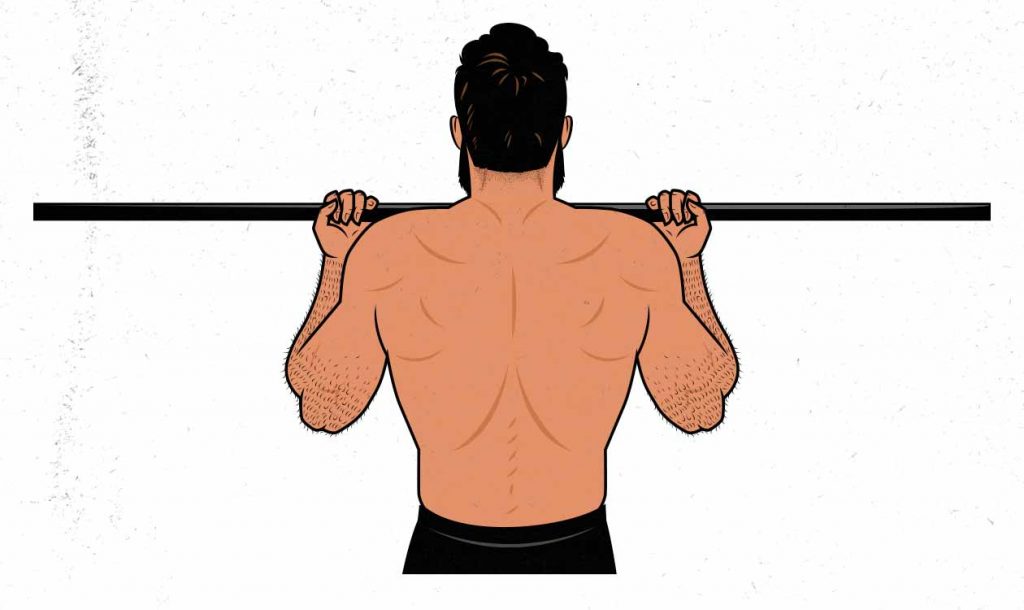

There are a few ways of doing a chin-up, with the most popular variations being the underhand “chin-up” and the overhand “pull-up.” The naming conventions aren’t consistent, though, and some people use the terms interchangeably.

An underhand grip gives you better leverage with your biceps, improving performance, and perhaps improving biceps activation. The overhand grip makes it harder for your biceps to help, making the exercise harder, but perhaps giving you slightly better activation in your lower lats.

You can also use a neutral grip, angled grip, or gymnastics rings. Those variations are great for your back and biceps, and they also tend to be a little easier on the elbows. I’m a big fan of the angled grip, but you’ll find just as many people who prefer the others.

Finally, when we’re talking about chin-ups, we’re assuming that they can be weighted as needed, allowing for steady progressive overload. That can be done by wearing a dip belt, using a weight vest, or even holding a dumbbell between your feet.

The Difference Between Rows & Chin-Ups

Muscled Worked

So the first thing to know about the barbell row and the chin-up is that although they’re both upper-body pulling exercises that work our back muscles, they’re often considered to be in two different categories:

- Rows are horizontal pulls, where we have the weight in front of our torsos and we pull it horizontally towards us.

- Chin-ups are vertical pulls, where we have the bar overhead and we pull ourselves vertically up to it.

It’s a bit of a weird distinction, though. Both horizontal and vertical pulls work similar muscles. They both train our lats, rhomboids, traps, rear delts, biceps, brachialis, forearms, and so on.

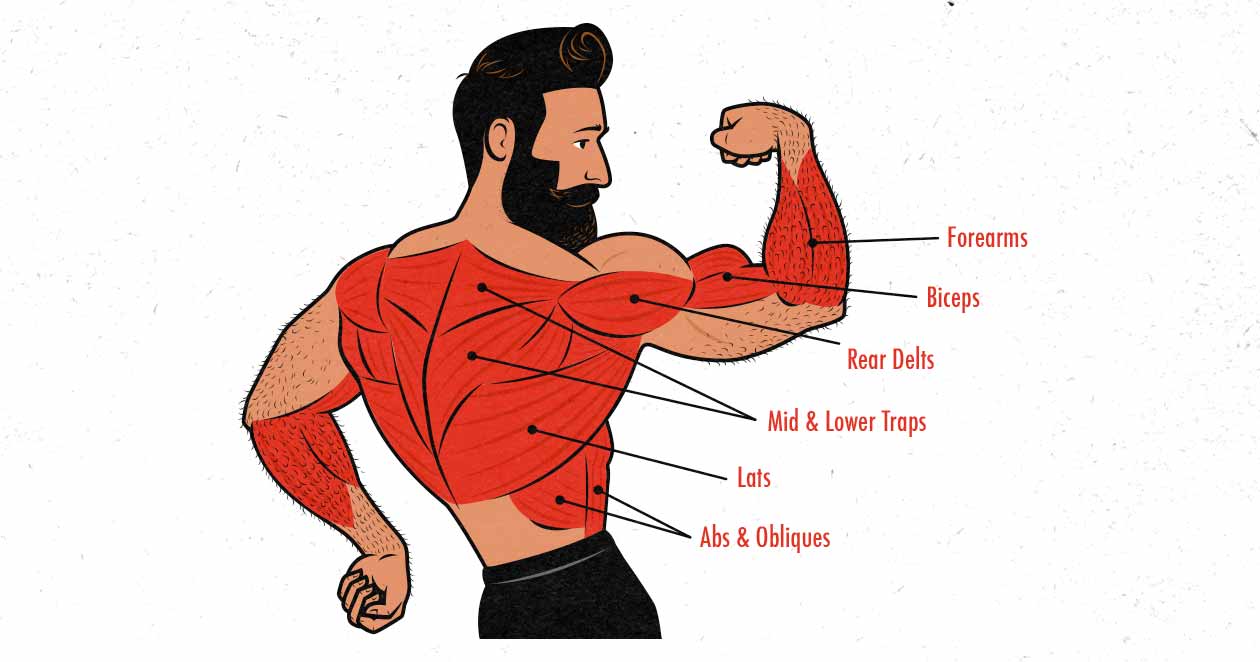

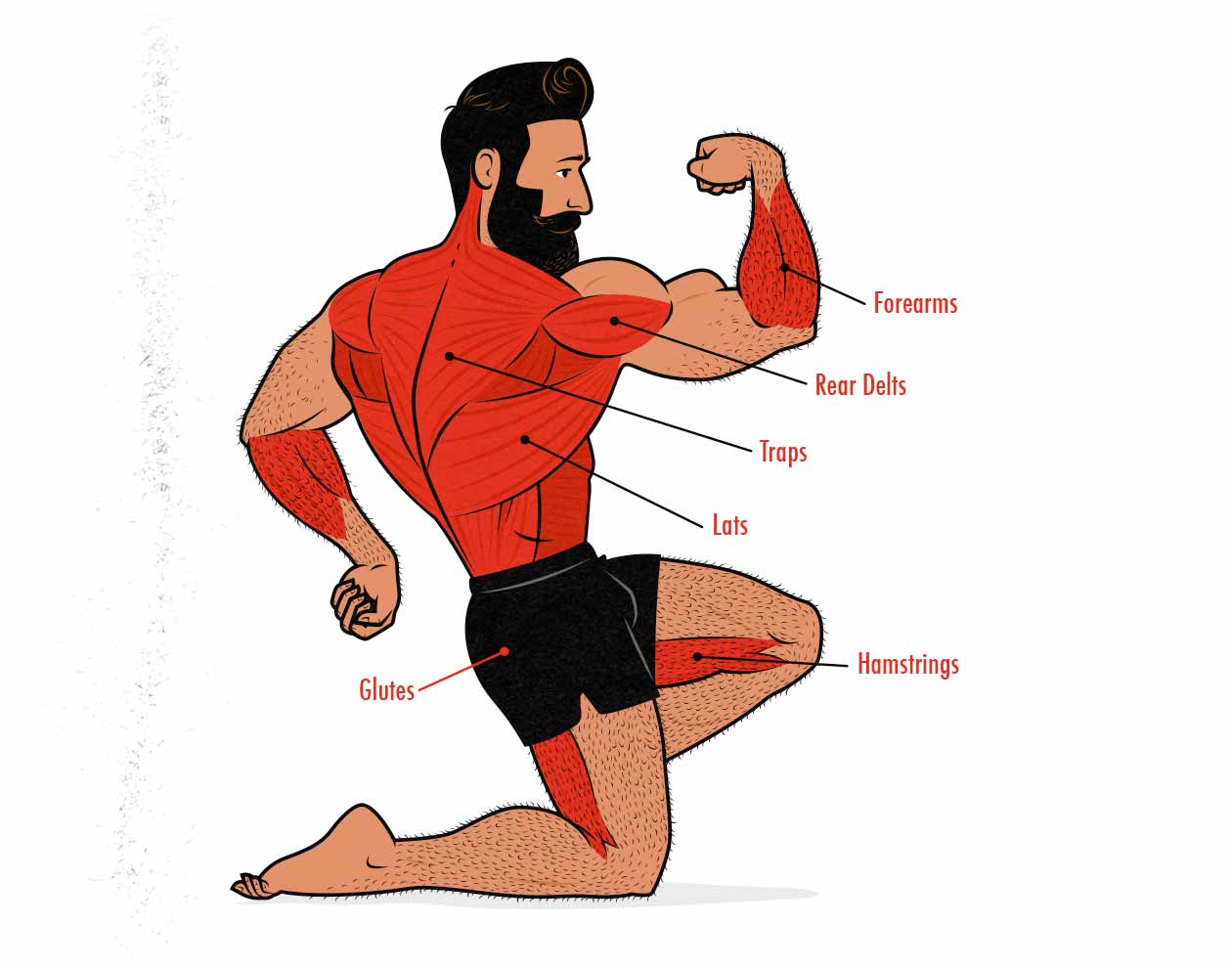

The main difference is that the chin-up does a pretty good job of stimulating growth in our abs and obliques, as shown above, whereas rows do a better job of stimulating our spinal erectors, glutes, and hamstrings, as shown below:

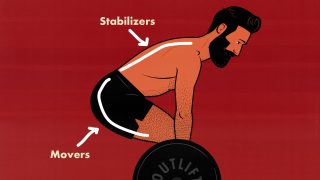

So what we’re seeing here is that the chin-up is more of an upper-body exercise, whereas the row is more of a full-body exercise. In fact, the barbell row works virtually the same muscles as the deadlift, just with a different emphasis. The deadlift pulls with the hips while the back muscles stabilize the weight, whereas the row pulls with the back muscles while the hips stabilize the weight.

In fact, the barbell row and the deadlift have such a good overlap that we consider the barbell row an assistance lift for the deadlift.

The chin-up, on the other hand, doesn’t have much overlap with the deadlift, front squat, bench press, or overhead press. As a result, we consider it one of the Big Five hypertrophy lifts by its own right.

There’s still something missing here, though. If the chin-up stimulates fewer muscles than the barbell row, why do we consider it a bigger compound lift?

Closed Versus Open Chain

With a chin-up, we’re pulling our bodies towards the bar. This makes it a “closed-chain” exercise, similar to squats and push-ups. Close-chain exercises are often better at working more muscles at once, and they can have better transference to general strength.

With some rowing variations, we’re pulling the weight towards us. This makes it an “open-chain” exercise, similar to the bench press. Open-chain exercises are often better for isolating various muscles, sometimes at the cost of stimulating less overall muscle growth. It’s often considered a bad thing, but I think it’s more accurate to just consider the pros and cons.

For instance, when comparing barbell rows against chin-ups, both are compound movements that work our abs or spinal erectors along with the muscles in our backs and biceps. No major difference in the amount of muscle mass worked or the practicality of the strength gains.

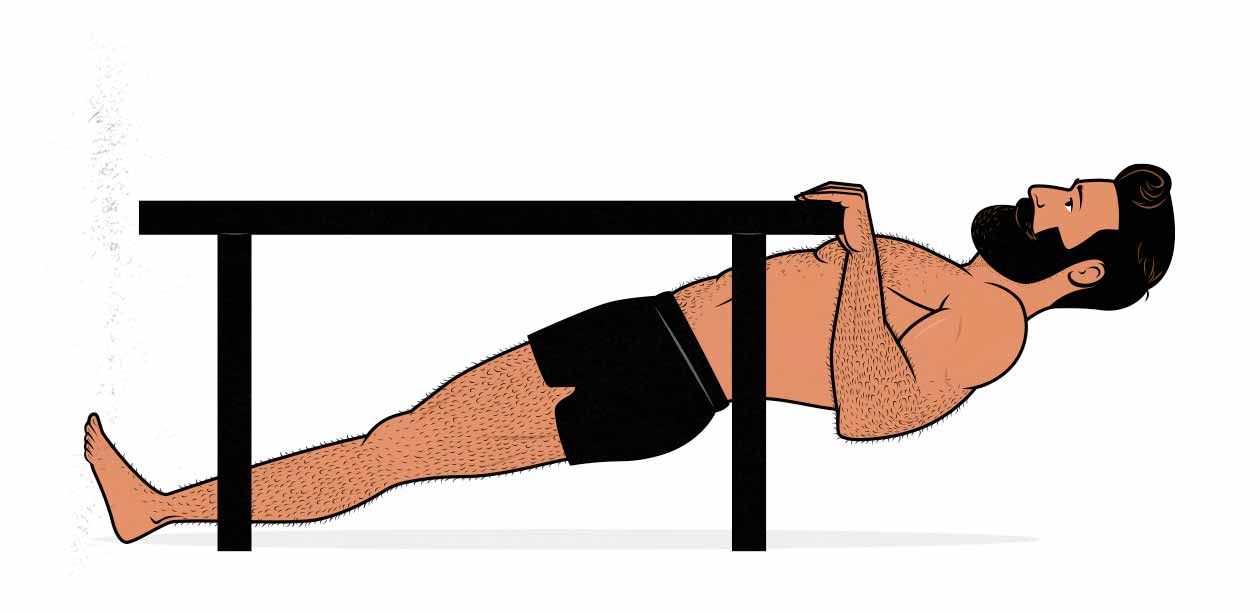

And besides, having an open chain isn’t an inherent feature of rowing movements. There are even inverted rows and table rows, where we’re pulling our bodies towards the bar, closing the chain:

Similarly, having a closed chain isn’t an inherent benefit of all vertical pulling movements. If we think of a lat pulldown, it’s the same movement as a chin-up except that now we’re pulling the bar down towards us, opening up the chain.

Regardless of how open or closed the chain is, both chin-ups and rows are perfectly functional compound lifts, and each has open and closed-chain variations anyway.

Range of Motion

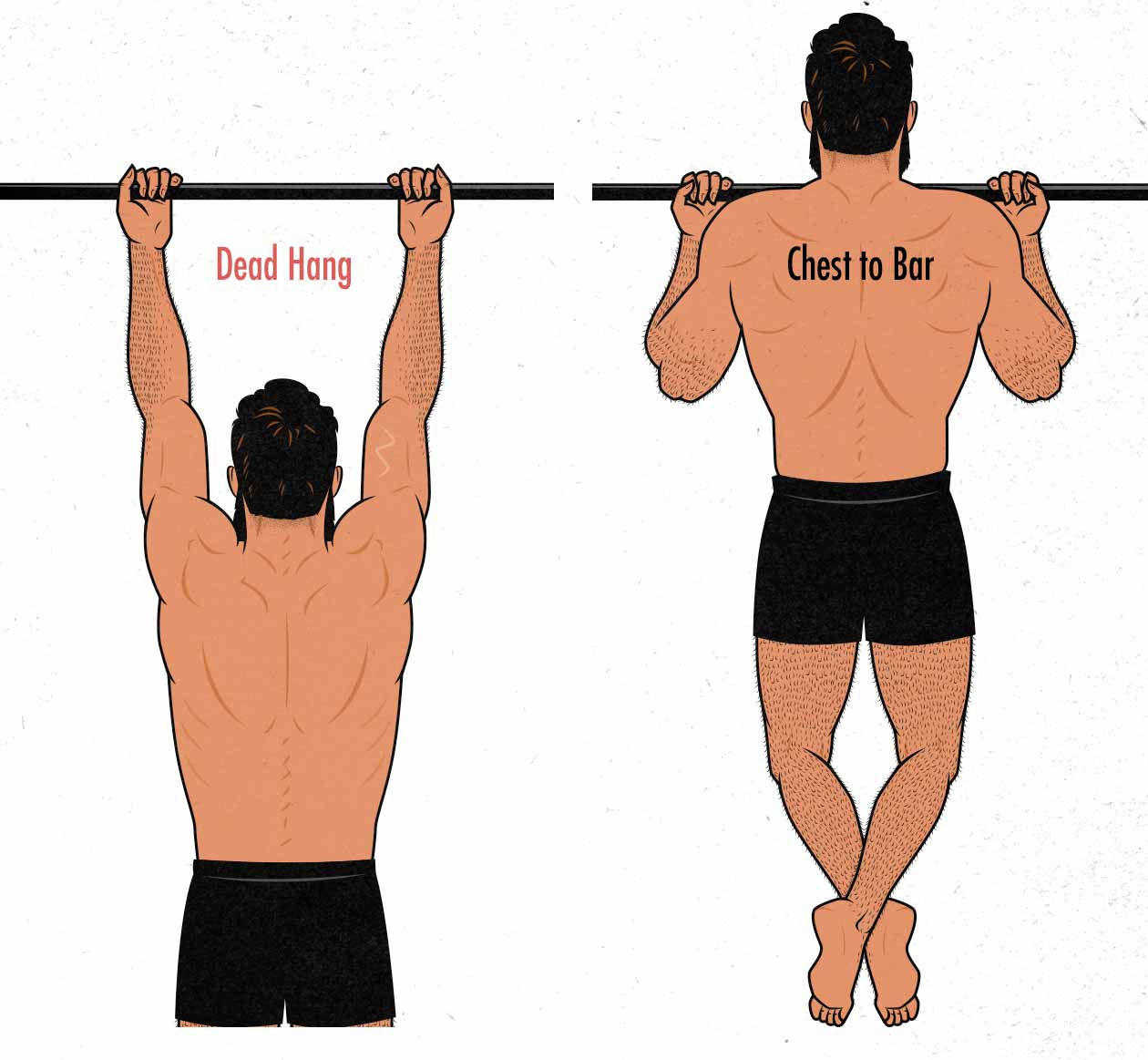

The most fundamental difference between the chin-up and the barbell row is the range of motion being used. With the chin-up, there’s a huge 180-degree range of motion, with the lats starting in a fully stretched position and are brought to a full contraction.

The same is sort of true with the biceps, where our arms start fully opened and finish fully flexed. However, our biceps attach at our shoulder joints, and the movement at our shoulders somewhat cancels out the movement in our elbows. When our biceps are stretched by our open arms, they’re shortened by our raised shoulders. We’ll talk more about our biceps in a moment, though.

Anyway, the obvious benefit of using a large range of motion is that our muscles need to do more overall work each rep, stimulating more muscle growth that way. A larger range of motion also tends to work a greater number of muscles. In the case of the chin-up, we even see our upper chest muscles getting involved at the bottom of the lift. A larger range of motion even stimulates growth in more regions of our muscles. In this case, because the chin-up works our lats through nearly twice the range of motion, we’d expect fuller development.

Perhaps the biggest benefit to the extra range of motion, though, is that the chin-up loads our lats in a stretched position at the bottom of the lift. With most lifts, it’s that stretched position at the bottom that stimulates the most muscle growth.

If we look at the barbell row, the situation is grim. Yes, we can pull our elbows a bit further behind our torsos, but our lats have so little leverage in that position that it doesn’t really amount to anything. What matters far more is how well our lats are loaded while stretched, and they aren’t loaded at all! That part of the range of motion is completely missing. At the bottom of the barbell row, it’s our hamstrings that are stretched.

So with the chin-up, we’re working our lats through a much larger range of motion that should be markedly better for building muscle.

Biceps Growth

The next difference to consider between barbell rows and chin-ups is biceps growth. Aside from the change of motion, biceps involvement is one of the major differences between the two exercises.

As a general rule, compound lifts often do a better job of stimulating growth in our torsos than in our limbs. Our hamstrings can lag behind if we grow them with just deadlifts, some heads of our quads will lag behind if we only squat, and the bench press is notoriously bad for stimulating triceps growth. Because of this, it’s fairly standard to start a workout with big compound lifts and then add in some extra isolation lifts for our limbs.

What’s neat about chin-ups is that not only are they amazing for bulking up our entire upper backs, they’re also great for bulking up our biceps. They may even be the best biceps exercise, given that they allow for such incredibly heavy loading. What’s even neater is that the benefit works both ways. Our lats and both biceps both work together to lift more weight than either could lift on their own, making for an incredibly heavy lift that stimulates a ton of overall muscle growth.

Since both our biceps and lats have such good overlap in the chin-up, when one gets near failure, instead of stopping the lift short, the other muscle group can pick up the slack and allow us to keep going. As a result, we’re often able to bring both muscle groups near enough to failure to stimulate an optimal amount of muscle growth.

If we look at the row, the situation is quite a bit different. The barbell row is generally done with an overhand grip, which puts the biceps into a position where they can’t exert much leverage, and so our much smaller forearm (brachioradialis) muscles take over. As a result, doing barbell rows tends to just result in a tired grip and tired forearms, whereas chin-ups tend to give a hearty biceps workout, too.

In fact, even if we intentionally try to bring our biceps into the row by using an underhand grip, it still doesn’t stimulate a comparable amount of muscle growth.

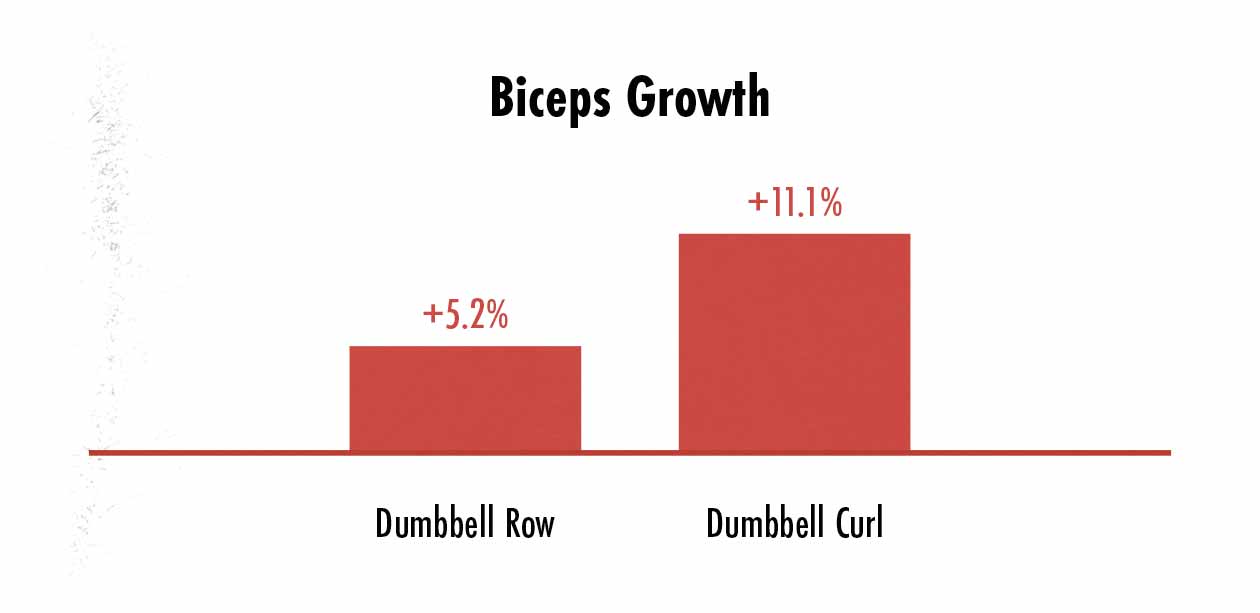

We don’t have a study that compares growth between the barbell row and the chin-up, but we do have a study by Mannarino et al that compares biceps growth between the dumbbell row and dumbbell curl. With both exercises, the participants used an underhand grip that was designed to involve the biceps, but the curl stimulated twice as much biceps growth.

Now, we can’t say that the barbell row is exactly like the dumbbell row, or that the chin-up is exactly like the dumbbell curl, but we can expect them to be somewhat similar given that they both involve the same grip position and range of motion in the elbows.

(Another conclusion we can draw from this study is that we should be doing both compound lifts and isolation lifts for our arms.)

Strength Curve

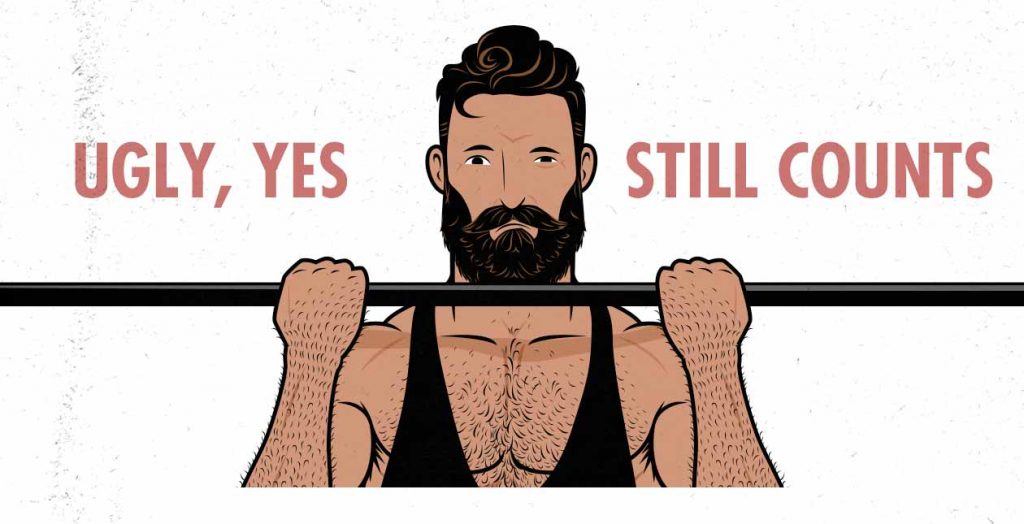

Another big difference between chin-ups and barbell rows is their strength curve. Chin-ups don’t have a perfect strength curve. A full range of motion means bringing our chests all the way to the bar, but because chin-ups are disproportionately hard at the very top of the lift, it’s common to have trouble pulling our chests all the way to the bar during our last couple of reps. Mind you, that’s easy enough to fix. If we’re trying to go all the way to failure, we can just keep doing reps until our chins stop reaching the bar (which makes sense for a lift called the chin-up).

Plus, the more important part of the range of motion is the bottom of the lift chin-up, where our lats are stretched under load. Fortunately, there are no strength curve issues at the start of the lift through the middle of the range of motion, allowing us to stimulate a ton of muscle growth.

Barbell rows, on the other hand, have one of the very worst strength curves of all lifts. The lift is stupidly easy off the floor but then quickly becomes damn-near impossible near the top. We can fix this somewhat by trying to accelerate the barbell through the range of motion, generating momentum at the bottom, where we’re strong, to help us bring the barbell up to our torsos, where we’re weak. But even then, the gnarly strength curve isn’t very good for stimulating muscle growth. (The t-bar row machine is designed to fix this strength curve issue.)

Because the chin-up’s range of motion is so much bigger and because the strength curve is so much better, we can stimulate quite a bit more muscle growth in our backs and biceps with every rep. This makes it quite a bit better for building muscle, but even better for building muscle would be training both movements, challenging our back muscles with two fairly different strength curves. I would argue, though, that we’d want to use the chin-up as our main back lift to work our backs through a full range of motion, and then bring in the row afterwards as an accessory lift to challenge our backs with a slightly different strength curve.

Lat & Trap EMG Activation

When we don’t have access to hypertrophy studies, what we can do is compare muscle activation from various lifts. However, it’s worth noting that EMG research isn’t a particularly good way of figuring out how much muscle growth a lift stimulates. In fact, of all the factors that we’ve mentioned in this article, this is likely the least important. Still, especially if we consider all of the other factors, EMG research can give us hints about which lifts emphasize which muscles.

Lat Muscle Activation

Perhaps the main muscle we’re trying to bulk up when doing back exercises is our lats. They’re beefy muscles that have a big impact on our aesthetics, they’re a big part of our general strength, and they’re a useful muscle when squatting and deadlifting.

In an attempt to figure out how to best train our lats, Dr Contreras measured lat activation in a variety of different back exercises:

- Chin-up: 108 mean lat activation, 159 peak

- Barbell row: 77 mean lat activation, 140 peak

- Dumbbell row: 63 mean lat activation, 140 peak

What we’re seeing here is that the chin-up activates our lats quite a bit more than both the barbell and dumbbell row. Combined with the fact that the chin-up works our lats through a larger range of motion with a better strength curve, and that we get a nice loaded stretch at the bottom, I think we can be fairly confident that the chin-up is quite a bit better for building the lats.

Trap Muscle Activation

Deadlifts and overhead presses are both great lifts for bulking up the upper traps, whereas chin-ups and barbell rows are often used to bulk up the mid and lower traps.

Muscle activation in the mid traps:

- Chin-up: 42 mean activation, 80 peak

- Barbell row: 68 mean activation, 146 peak

- Dumbbell row: 123 mean activation, 226 peak

Muscle activation in the lower traps:

- Chin-up: 58 mean activation, 104 peak

- Barbell row: 52 mean activation, 112 peak

- Dumbbell row: 99 mean activation, 160 peak

What we’re seeing here is that our traps are worked quite a bit better by barbell rows, and even better by dumbbell rows. Again, we always need to be cautious with drawing conclusions from EMG research, but I think this highlights why both horizontal and vertical pulling movements are important for building up our backs.

Lower-Back Fatigue

I’ve heard some hypertrophy experts argue that dumbbell rows are better for building muscle than barbell rows because it keeps our lower backs fresh for our squats and deadlifts. I’ve heard other hypertrophy experts argue the exact opposite, saying that the barbell row is the better lift because it strengthens our lower backs, allowing us to squat and deadlift more easily. Both of these ideas are true.

If you’re trying to strengthen a weak lower back, the barbell row is a great way to increase your lower-back training volume, allowing you to bulk it up more quickly. On the other hand, if the volume on your lower back is already high, then you might want to choose rowing variations that don’t add extra stress to your lower back. Fortunately, there are plenty of rowing variations that remove our posterior chains from the lift, such as the famous “three-point” dumbbell row:

With the three-point dumbbell row, we’re supporting our torsos with our other arm, taking our posterior chains out of the mix, and allowing us to focus on just lifting the dumbbell, driving our elbows back. Plus, another nice thing about the 3-point dumbbell row is that we can stretch out our upper back muscles a little bit extra at the bottom, giving it a larger range of motion. (I’ve got this guy with both his feet symmetrically on the floor, but you can put your leg wherever you want. Some people prefer a split stance, others like to put a knee up on the bench. Whatever rows your boat.)

Another great chest-supported rowing variation is the t-bar row, which again gives us a better stretch at the bottom and also gives us a better strength curve for our lats. And if you don’t have dumbbells or a t-bar row machine, you can do inverted rows by setting up your barbell in a low position and then rowing yourself up into it.

Anyway, this means that one advantage of the chin-up is that it doesn’t strengthen our posterior chains, allowing it to slot in nicely alongside the squat and deadlift without any interference whatsoever.

But that also means that one disadvantage of the chin-up is that it doesn’t strengthen our posterior chains. It’s a whole separate lift that has almost no effect on powerlifting performance, which may be why it’s so often neglected in barbell strength programs (such as StrongLifts 5×5).

Programming Rows & Chin-Ups

We consider chin-ups one of the main lifts that we rely on to build a big, strong, healthy, and aesthetic physique. Because of that, we do chin-ups with the same emphasis and fervour that we do our squats, deadlifts, bench press, and overhead press. We often do them first in a workout, we go heavy, we give them our all, and we do a greater number of sets (2–6 per workout). With rows, on the other hand, we consider them an accessory lift for either the deadlift or chin-up, and so we slot them in after our main lifts, often doing them in higher rep ranges, with shorter rest times, and for fewer sets (2–3 sets per workout).

Because chin-ups have so little overlap with the other big compound lifts, we can fit them into any workout, potentially even doing them as circuits or supersets. For example, one of my favourite ways to do chin-ups is alongside my front squats, both of which can be done in a typical rack:

- Front squats, rest 1–2 minutes.

- Chin-ups, rest 1–2 minutes.

- Front squats, rest 1–2 minutes.

- And so on.

Another popular way to do chin-ups is to slot them in alongside overhead presses, which is a form of antagonist superset, where opposing muscles are worked one after the other, improving the performance of both, and perhaps slightly increasing muscle growth.

After doing chin-ups, if your lats tend to lag behind, you might want to add in a bit of extra back work. Rows can be good for this, but so can straight-arm pulldowns or overhand lat pulldowns. If you want extra work for your traps or rear delts, face pulls and reverse flyes are good choices. Or, if your biceps could use a bit of extra work, you might want to do some biceps curls. Doing two back/biceps lifts per workout often works quite well, but you can pick which areas you want to emphasize.

With the barbell row, we need to be careful not to let it interfere with our squats and deadlifts, and so exercise order can get tricky. If we tire our lower backs with rows, it might limit our performance on the squat and deadlift. On the other hand, if we tire our lower backs with our squats or deadlifts, we might not be able to row heavy enough to stimulate any lat growth. It’s tricky, and oftentimes choosing a chest-supported or dumbbell row can be the easier solution.

My favourite way of programming rows is to do antagonist supersets, slotting them alongside my bench press:

- Bench press, rest 1–2 minutes.

- Barbell rows, rest 1–2 minutes.

- Bench press, rest 1–2 minutes.

- And so on.

Another option is to do them right after chin-ups. That way our lats are already a bit fatigued, allowing us to bring our lats close to failure before our lower backs start to limit us.

Key Takeaways

The barbell row is good for building the muscles in our hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors, making it a great assistance lift for the deadlift and a more relevant back lift for powerlifters. However, although it’s a good lift for training our posterior chains, its short range of motion, poor strength curve, and lack of biceps involvement means that it isn’t ideal for training our backs or biceps.

The chin-up, on the other hand, has a much larger range of motion, and it loads our lats under a heavy stretch, making it a better muscle-building exercise for our upper backs and biceps. The chin-up also does a good job of training our ab muscles—perhaps better than any other compound lift. So, although it doesn’t have much overlap with the deadlift or with powerlifting, it brings something unique to the table, and it makes a good foundation for our back training.

Both the barbell row and the chin-up are great lifts, but we prefer to slow the barbell row as an accessory lift for the deadlift, whereas we make the chin-up one of the main lifts in our programming, giving it a far higher priority.

Anyway, if you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. We also have our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program and Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program for beginners. If you liked this article, I think you’d really like our full programs.

I’m on my second cycle of the Outlift 4-day hard program and absolutely loving it. A question, though: I’ve seen mentioned in a couple of articles that you recommend doing up to 6 sets of the Big 5 lifts, yet they only seem to be programmed for a maximum of 5 – why’s this?

Woot, that’s awesome! 😀

We use up to 5 sets on the main lifts and then up to around 4 sets on the assistance and accessory lifts. That gives us enough volume overall between the two different lifts. We also tend to use longer rest periods (except in that first phase), meaning we get more out of each set. And we tend to use moderate rep ranges (7–20). It’s more in the lower rep ranges that we may need lots of sets per exercise.

But there wouldn’t be anything wrong with doing 6 sets. We just get the volume we need a different way in this program.

Hats off, Shane, for this article. The best content I have gone through about rows vs chin up.

You have nicely elaborated the differences in range of motion, loading under stretch for lats, and strength curve differences. These are very informative for me and many others. All these factors heavily favor the chin up, preferably weighted chin-up. Plus that they don’t mess up with squats and deadlift giving them another plus point to be included in powerlifting workouts.

EMG results showing that dumbbell rows work the middle and lower traps better that chin up and barbell rows is quite surprising because they use the least amount of weight.

For barbell rows I think best way to incorporate them with maximum loading and aggression is to use as alternative to deadlift. Once we can lift very heavy with deadlifts, it’s frequency decreases accordingly. I mean very few non powerlifters will pull 3x bodyweight deadlifts once or twice a week so barbell rows can be used in place of deads in alternating workouts.

I think we all are different anatomically and different exercises work somewhat differently for us. Some people will get more lats from barbell rows and some will feel more lats with chin up.

My personal favorite upperbody pulling exercise is weighted pull ups but I mainly feel it in my traps and less in my lats whereas unsupported T-bar rows (pendlady style) feel exclusively in my lats and less in my traps.

Thank you, Farhan 🙂

Yeah, I agree. I consider barbell rows to be an assistance lift for the deadlift. One day you do deadlifts, another day you do barbell rows. That way you’re hitting your posterior chain twice per week with complementary movements. That’s a great way of doing it.

Great article… as always. 🙂 However I want to ask about the ratio between the 2 exercises. If we use the chin up as main lift and use less often the barbell row, aren’t we going to make some bad changes in out posture. I mean that there are few places on the net, where I have read that the muscles which are trained with vertical pulling are working like the muscles with which we pull horizontally- they pull our bodies forward and make us slouching. So if we emphasize on chin ups, aren’t we in danger of muscle imbalance between traps and lats?

Hey Adnan, thank you!

That kind of muscle imbalance can happen. You’ll see it sometimes, guys with shoulders sloped and sounded forwards. But posture is fairly complicated, and the root of the problem is not usually so simple as spending too much time benching and doing chin-ups, too little time rowing. But I don’t disagree that it’s better to develop the muscles of our backs with a balanced routine that includes both vertical and horizontal pulling.

One thing to keep in mind is that the traps are worked quite well with the deadlift, which is a sort of horizontal pull, and which we consider a main movement. So even if we prioritize the chin-up over the row, we still have those muscles being addressed with their own main movement. Plus, the front squat and overhead press also do a great job of strengthening the postural muscles in our posterior chains, and those are main lifts, too.

So it’s not that the muscles we work with the row aren’t important, it’s just that there are already a lot of overlapping lifts developing those muscles, and so the row can move back a little bit.

Thanks for the answer, Shane!

I completely agree with you that muscle imbalance between horizontally pushing and pulling muscles is not the only reasons for problems with the posture. In fact it is quite more complicated- lower back, abs and even glutes. The main reason is however the will to stay straight or just to lean forward.

And about the compound lifts- yes, I agree with you that many people forget the fact that the compound lifts don’t work only one muscle group. One of the brightest examples for this is the military press- only anterior deltoids exercise, according to many. But honestly, many times I have more serious DOM in my upper pecs than in my front part of the shoulders. 🙂

Yes, totally! I love the overhead press for the upper chest 🙂

Shane, I like your info. I’m 52, and always looking for a spin on programs centered around the big lifts. I’m a big guy, shoulders are shot from years of working with my arms over my head and being stupid. They don’t bother me unless I do chin-ups/pull-ups as I’ve learned to protect them. Physics/gravity dictate a limitation on pulls without chin-ups or machines, and as a minimalist garage warrior I’ll never go to a gym. I know you consider rows to be more of a complimentary exercise to deadlifts. I’d like to get a vertical pull effect but can’t figure out a way to do it without sidelining myself for 2-3 weeks. I do some extra biceps work in an effort to cover what I’m missing with chin-ups.

Hey Chris, thank you!

Yeah, I mean, sometimes we have to work around our bodies. That’s okay. Sounds like you’re doing a good job of it. If you haven’t already tried, you might want to give gymnastics rings a shot. Your hands will be able to move and rotate freely as you pull yourself up, which can make them much easier on the shoulders. And they’re a pretty cheap addition to a garage gym 🙂

Hi Shane, great article and depth. Really appreciated.

I was wondering, is the strength curve of the inverted row any different from the barbell row? I do a lot of weighted rows on gymnastics rings and find them pretty challenging as well as a way to naturally open the scapula at the bottom of each rep. But I suspect their curve is no better than barbell or machine rows – easiest at the bottom, toughest at the top. Does that seem about right to you?

Thanks dude!

Hey Duncan, thank you!

Yeah, you’re right. Inverted rows have a similar strength curve to barbell and dumbbell rows. Machine rows, though, can have a better strength curve. If you train at a gym that has a t-bar row machine, those are absolutely fantastic for building a bigger back. It’s a rare example of a machine that trains our muscles better than free weights can.

With that said, the resistance curve of a lift is just one factor. Rows and inverted rows are still good lifts. They just aren’t perfect. And that’s okay.

Hey man, I guess it’d help us all to admit we’re like an inverted row. Not perfect, but that’s ok. And maybe to be one of life’s T-Bar rows would be…a bit dull 😉

Thanks for the reply dude!

Ahaha, totally!

Hi Shane – I hope its not too late to ask a question about this awesome article. You have done a great job of explaining how rows and chins work the body – I enjoy both but I have concentrated mostly on bb rows because I am ashamed to admit that I cannot perform even one complete chin or pull-up. I’ve been pretty much stuck at 3/4 rep on the chin, 1/2 rep, 1/4 rep for a few sets and then I’m done. Because I can’t do them I have neglected them but want to get the benefit after reading this article. I do have a lat pulldown machine but some say that is not the same (closed vs open chain as I learned from this article) and that it doesn’t have cross-over effect. Perhaps I just need to be much more consistent at doing negative chins? How frequently can I train it in order to really improve? Do you have any suggestions? Thank you – glad I discovered your website.

Hey Mason, thank you!

It’s true that lat pulldowns and chin-ups aren’t quite the same. You’re right that one is open-chain and the other closed. But I think the difference is often overblown. Both are vertical pulls that place very similar demands on your pulling muscles. Consider the bench press and push-ups. They’re different exercises, yes, but both will do a great job of bulking up your chest.

I’d do the lat pulldowns. If your goal is to get better at chin-ups, too, then maybe keep starting your workouts with a set of 3–4 reps. Then move over to the lat pulldown machine and get your volume in: 3–4 sets of 6–12 reps. You can do them with an underhand grip, as you’d do a classic chin-up. You can do them with a neutral grip, too. The wide overhand grip is good too, but it may translate less well to your chin-up strength. I’d mainly focus on underhand and neutral grips.

You can train your chin-ups/lat pulldowns 2–3 times per week. I do them twice per week. My back seems to like a higher volume, so I often do more sets than usual. I might do 3–4 sets of bench press for my chest, but I’ll do 5–6 sets of chin-ups/pulldowns for my back.

Thanks for your reply. I had been doing a similar regimen as you outline before and will go back to it now that I have my chin bar set up after relocating. I’m going to dedicate a “specialization” day to chins every 4 days and super-set with overhead pressing. Cheers and thanks again – your site is full of great info – one of the very best.

My pleasure, man! Good luck!

Great article thank you. I think there is a typo in the final paragraph: “slow” should be “slot”.

Thank you, Matt!

Oi, yes. You’re right. I’ve fixed it.