How to Do Cardio—The Complete Beginner Guide

The guidelines for general health are simple: you need at least 150 minutes of cardio per week. If the cardio is twice as hard, you only need half as much. More on that in a moment.

But there’s more to cardio than merely putting in the time. You also need to provoke an adaptation. You need to train in a way that improves your cardiorespiratory fitness. That way, you get the benefits of having increased mitochondrial density, a higher VO2 max, more blood vessels, and a lower resting heart rate.

Marco has over a decade of experience helping people improve their cardio, with clients including college, professional, and Olympic athletes. It doesn’t need to be that complicated. We’ll explain the basics of cardio, give you a beginner routine, and then show you how to progress to more difficult workouts.

What is Cardio?

Cardio is short for cardiorespiratory exercise. It’s any type of exercise that stimulates your cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels) and respiratory system (lungs and blood vessels). These are the systems that allow you to breathe in air, convert it into energy, transport it throughout your body, and then dispose of the waste products.

The most intense types of physical activity are anaerobic—they don’t use oxygen. When you sprint or lift weights, most of the energy comes from within your muscles. But you can’t store very much energy there. You’ll gas out within about a minute.

Cardio is designed to improve your aerobic fitness—your ability to use oxygen. It won’t help you sprint faster, but you’ll be able to run further, maintain a faster pace, and have an easier time catching your breath afterwards. It won’t help you lift heavier weights, but you’ll recover faster between sets, and the extra blood vessels and mitochondria might help you build bigger muscles (study, study).

Getting fitter also lets you use oxygen more efficiently while at rest. You’ll be able to fuel your body with fewer pumps of your heart, giving you a lower resting heart rate.

The Benefits of Cardio

Cardio can reduce your risk of developing almost every chronic disease, make you look younger, and increase your lifespan by 3–8 years (study). It’s especially good at improving your cardiometabolic health, warding off heart attacks, strokes, insulin resistance, and diabetes (study). It also reduces inflammation, improves gut health, and strengthens the immune system (study). And it improves energy, enhances cognition, and reduces the risk of anxiety and depression (study).

Cardio is good for you in two distinct ways:

- It’s healthy to be active. Cardio offsets the harms of spending most of the day sitting (study, study). This seems to add around 2 years to your lifespan (study).

- It’s healthy to be fit. If you follow a cardio routine that improves your fitness, you’ll get the health benefits of having a more robust cardiorespiratory system: greater mitochondrial density, a more efficient heart, better blood flow, and improved exercise performance. This could add another 5 or so years to your lifespan (study, study).

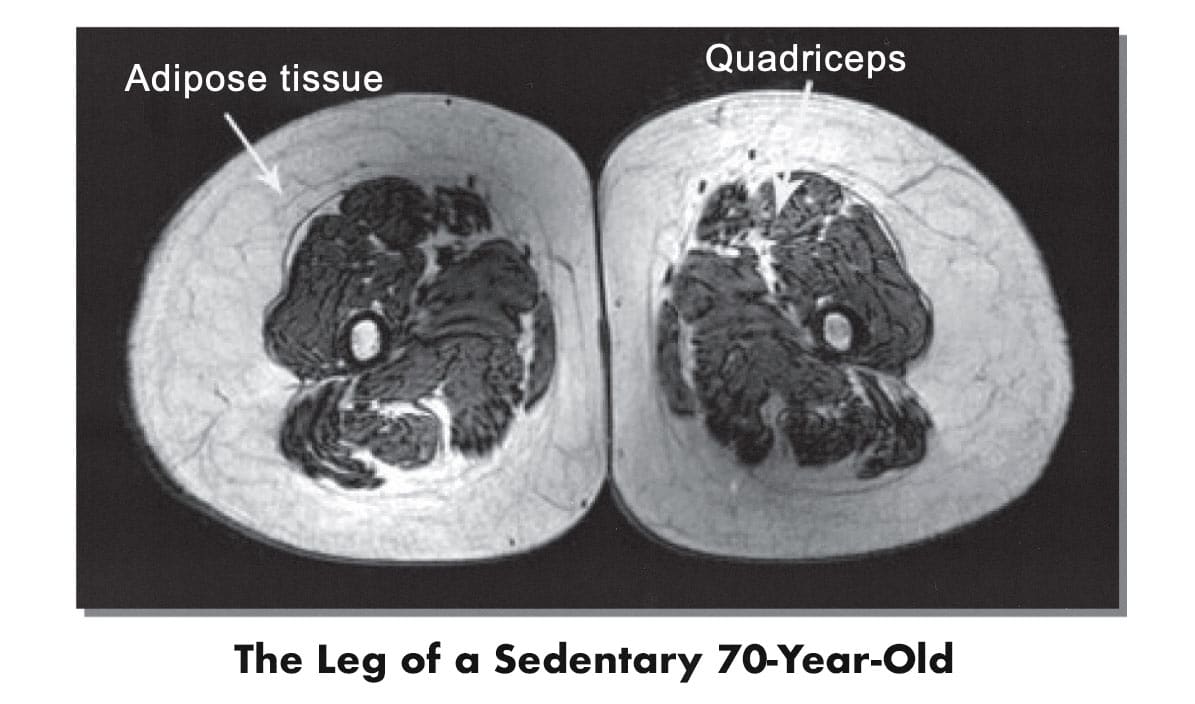

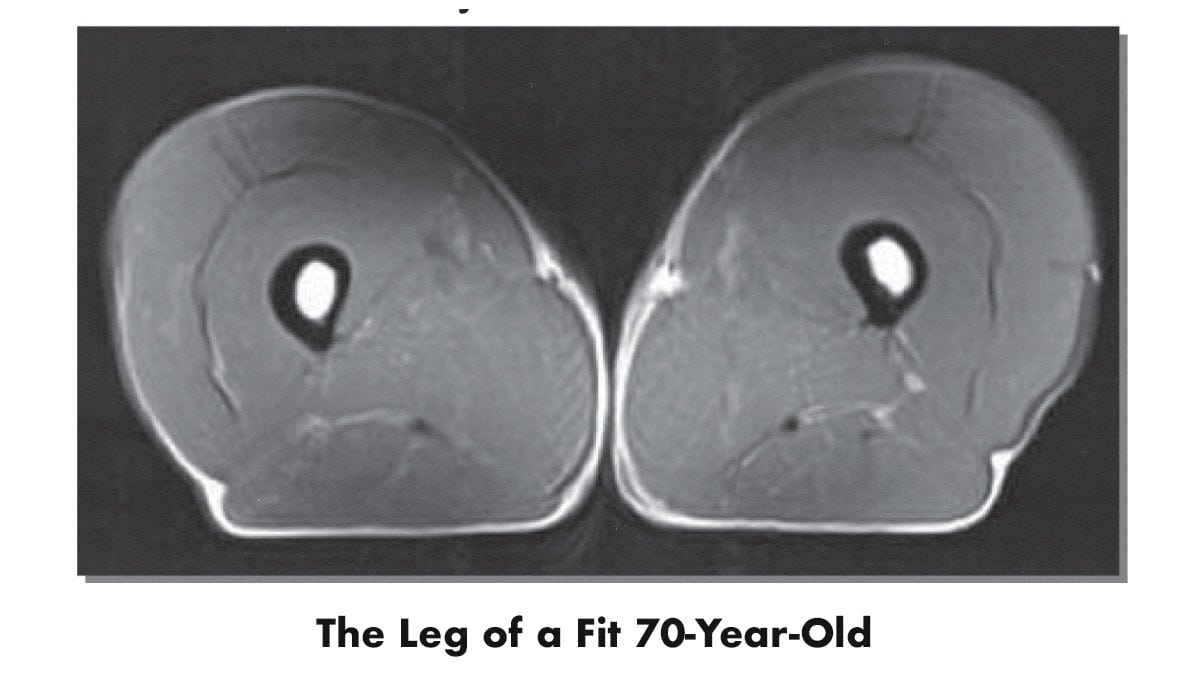

The benefits of cardio are easy to see. Above is an MRI scan of a sedentary man’s thigh (study). Notice how his bones are thin and rarefied, his muscles are withering away, and his body composition is beset by fat. He’s a typical 70-year-old, and it shows.

This second MRI scan is of a triathlete. He can swim for 1.5 kilometres, bike for 40, and then run for 10. His bones are thick and dense and pearly white. His legs are made up almost entirely of muscle. He has barely any fat, and all of it is right beneath the skin, where it cannot harm him. He’s 70 years old but has the body composition of a 30-year-old athlete.

Metabolic Equivalents (METs)

A metabolic equivalent (MET) is the amount of energy you use while sitting quietly. If you go on a stroll, you burn around twice as much energy as you do when sitting (2 METs). A brisk walk burns around four times as much energy (4 METs). Jogging and rucking burn around seven times more energy (7 METs). Sprinting burns around twelve times more energy (12 METs).

Energy is calories. Listening to an audiobook while going on a brisk walk (4 METs) burns four times as many calories as reading a novel in your favourite chair (1 MET). That’s great for people lugging around extra body fat. It’s less great for skinny people struggling to gain weight. But the benefits of cardio go far beyond burning fat, so even skinny people benefit from it.

The more intense the activity, the harder it is for your cardiorespiratory system to supply your body with enough energy to sustain it. That challenge provokes an adaptation, improving your ability to sustain higher intensities of exercise. If you keep pushing against your limits, your boundaries will gradually expand. That’s how you get into great shape.

Current exercise guidelines recommend at least 500 “MET minutes” per week. A brisk walk is around 4 METs, so you’d need to walk for at least 125 minutes per week. A light jog is around 7 METs, so you’d need to jog for at least 70 minutes per week.

The catch is that you need to be doing cardio. Sitting quietly for 500 minutes isn’t a very good way to get your MET minutes in. Hypertrophy training (6 METs) is better, but it still isn’t cardio. It isn’t designed to provoke cardiorespiratory adaptations. It’s better to lift weights to build muscle and do cardio to get fitter. More on combining lifting with cardio here.

The 3 Types of Cardio

I’d forgive you for assuming walking is low-intensity exercise, jogging is moderate-intensity exercise, and sprinting is vigorous-intensity exercise. Unfortunately, whoever coined these terms had a stranger idea. A brisk walk is moderate intensity (3–6 METs), and both jogging and sprinting are vigorous intensity (7+ METs).

It would be simpler if there were a system that broke cardio down into the three intensities we care about, dividing up activities like walking (4 METs), jogging (7+ METs), and sprinting (12+ METs). So that’s what we’ve done:

- Easy Cardio (Zone 2) is an intensity you can sustain almost indefinitely, talking as you do it. Your energy comes from your aerobic system. Think of brisk walks.

- Medium Cardio (Zones 3–4) is an intensity your aerobic system can’t quite sustain, forcing you to get some energy from your anaerobic system. It’s fatiguing, so you can only sustain it for 20–60 minutes. Think of jogging.

- Hard Cardio (Zone 5) is fueled mostly by your anaerobic system. You can only sustain it for seconds or minutes. Think of sprinting.

These zones provoke different adaptations. The best way to become fit is to combine all three, but it usually helps to master the easier zones before advancing to the harder ones. Let’s talk about how to do that.

Easy Cardio (Mostly Aerobic)

Most beginners start with brisk walking, but as you get fitter, easy cardio can include slow jogging, light rucking, and relaxed cycling. You’ll know you’re in the right zone when you can only just barely maintain a conversation while doing it. Most people will be able to breathe through their noses. It should get you to 60–75% of your max heart rate.

This is exercise powered by your aerobic system, giving you clean and sustainable energy. You’ll hear it called Low-Intensity Steady-State (LISS), Long Slow Distance (LSD), Cardiac Output, or Zone 2 Cardio. It causes your heart to adapt by stretching wider, drawing more blood in, and pumping great volumes with every heartbeat. To get that adaptation, your heart needs to be beating relatively slowly, giving it time to fully inflate with blood.

Endurance athletes live on easy cardio. It often makes up 80% of their workout programs. They love it because it doesn’t produce much fatigue, allowing them to spend more time training. It’s also important for beginners. The more aerobic energy you can produce, the more energy you’ll have when doing any form of exercise.

You should be able to sustain your pace for well over an hour. It’s okay to start with 20-minute workouts, but you want to get up to 30+ minutes within your first few months of doing cardio. Even better if you can do a 60–90 minute session once per week.

Medium Cardio (Aerobic to Anaerobic Threshold)

Medium cardio includes jogging, rucking, and cycling at a steady pace. You might be able to squeeze out a few words between breaths. You’ll probably need to breathe through your mouth. It should get you to 75–90% of your max heart rate. You should be able to sustain your pace for 20–60 minutes.

This is exercise fuelled by both your aerobic and anaerobic systems, creating waste products that cause pain and fatigue. You’ll hear it called Moderate-Intensity Steady-State (MISS), Maximum Lactate Steady State (MLSS), or Tempo. It makes you better at clearing waste products and converting them into energy. For example, your anaerobic system burns glycogen (carbs), which produces lactate as a waste product. Your aerobic system can convert that lactate into more energy.

Medium cardio is the most classic type of cardio. It’s a vigorous form of exercise that floods you with pain and endorphins, creating a barbaric euphoria. Beginners can use it to get better at jogging, rucking, or cycling. Athletes use it to get better at going faster. For example, marathon runners use “tempo runs” to practice running at their race speed.

As a beginner, your goal is to get better at the type of cardio you’ve chosen. If you’ve chosen to run, this is the zone where you get better at running. Eventually, you’ll be able to run slowly for easy cardio, and you’ll unlock the ability to run faster for hard cardio. Medium cardio will become less important. But as a beginner, medium cardio is magic.

Your medium cardio workouts will usually be 10–30 minutes long, and you can do them 2–4 times per week.

Hard Cardio (Mostly Anaerobic)

Hard cardio includes sprinting, biking uphill, skipping rope, and assault bikes. You’ll need to breathe through your mouth. You won’t be able to talk. You’ll be left desperately gasping for air when you stop. It should push you past 90% of your max heart rate. It’s sustainable for a few seconds up to a couple of minutes.

This is exercise fuelled by your anaerobic system, emphasizing power over sustainability. High-Intensity Interval Training uses short bursts of hard cardio. For example, you might sprint for 1 minute and then walk for 3 minutes. That’s one rep. You might do 3–5 of those reps. It’s great for improving your speed, power, and VO2 max. It’s also good for gaining muscle and strength.

Hard cardio is by far the most fatiguing form of exercise. HIIT workouts usually last 7–20 minutes. Most athletes only do 1–2 of those workouts per week. You can get powerful benefits from those short workouts, but you still need to spend most of your time doing easier cardio.

Beginners should hold off on HIIT. It’s better to start by building an aerobic base (e.g. brisk walking). Then, learn how to go faster with good technique (e.g. slow jogging). Once your technique is sound, you can start going faster (running), eventually unlocking HIIT (sprinting).

When you start doing harder cardio, start with slower intervals that last for longer. For example, start by running fast for 2 minutes at a time. When that’s going smoothly, run even faster for 90 seconds. Then a minute.

How Much Cardio Should You Do Per Week?

Most health organizations recommend doing at least 150 minutes of easy cardio per week. Medium cardio (like jogging) counts for double. Hard cardio (like sprinting) counts for four times as much. We’ll set you up with a routine that starts at the minimum and gradually works your MET minutes higher.

Note that HIIT includes both high-intensity bursts and low-intensity rest periods. When you average out the intensity, you get around 8 METs, making it about as efficient as jogging. That means HIIT counts for double, not quadruple.

Anything that gets your heart rate high enough can count as cardio for a beginner (study, study, study). If you sprint up a flight of stairs for 30 seconds (hard cardio), that adds 2 minutes to your weekly total. You’d need to do that 75 times per week to get your 150 minutes in.

That gives beginners a few different ways to satisfy the guidelines:

- A 7-minute walk after breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

- A brisk 20-minute walk every morning.

- Three 25-minute jogging sessions per week.

- One 40-minute walk, two 20-minute jogs, and one 15-minute HIIT workout.

Different cardio routines produce slightly different adaptations. If you want the most robust adaptations, mix the different types of cardio together. We’ll start with a foundation of walking and gradually build upon it.

Also, keep in mind that this is the minimum amount of cardio you should do. As long as you aren’t suffering from overuse injuries (like shin splints or aching knees/hips), you can increase the time you spend doing cardio by up to 10% per week.

What Type of Cardio Should You Do?

We’ll use the walking/jogging/rucking/sprinting stream of cardio because it’s the most accessible, the most natural, and it’s what we have the most experience with. Marco has almost two decades of experience helping high-level athletes improve their running performance and cardiorespiratory fitness for sports like rugby. He knows how to get people into absolutely incredible shape.

I’m less experienced. I tried jogging for the first time in my early twenties and gave up after three sessions because of crippling shin splints. It wasn’t until last year, at 34, that I finally learned how to run. I know what it’s like to be a confused beginner. I want to help you get through that confusion.

When we say walking, rucking, and running are “natural,” we mean you already know how to do them. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors would walk to a hunting ground, chase down their prey, and carry the carcass back home. These activities are baked into our DNA, and we’ve been practicing them our entire lives.

But you’re free to choose any type of cardio you want. Here are some other forms of cardio that are easy to program and progressively overload:

- Cycling

- Swimming

- Rowing

- Ellipticalling

- Treadmilling

The Cardio Program

We want to give you an actual cardio program you can follow, starting at the beginner level and progressing from there. This is the cardio program I used this past year. I’ve only just made it to level 3. Marco’s been at level 3 for decades.

Note that there are many different ways to design cardio workouts. This is our approach, but you might find others, and those other workout programs might be great, too.

Level 1 (Easing In)

We recommend beginners start with a brisk 20-minute walk every morning. Brisk walks won’t be enough forever, but they challenge most beginners. For as long as they’re challenging, they provoke great gains in fitness and health.

Walking will get your feet, shins, knees, and hips used to the stress of pounding away at the pavement, grass, dirt, or sand. The early morning sun will build a strong circadian rhythm, improving your sleep at night. And your cardiorespiratory fitness will begin to improve.

| Day | Workout |

|---|---|

| Monday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Tuesday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Wednesday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Thursday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Friday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Saturday | 20-minute brisk walk |

| Sunday | 20-minute brisk walk |

You’re free to consolidate some of your walks into longer sessions. Instead of walking for 20 minutes seven times per week, you could walk for 50 minutes three times per week.

Walk as fast as you can. Imagine you’re late for a date with someone who loves the smell of sweat. It might feel forced at first, but it will quickly begin to feel natural. You should be able to talk but not sing. And when you talk, it should feel a little difficult, a little stilted.

Try to enjoy it. Depending on your neighbourhood, you can bask in the serene beauty of nature, tune out your worries with a good audiobook, or scour the streets for signs of thieves. Walking isn’t a punishment. You’ve chosen this. This is the life you want.

*I live in a somewhat dangerous neighbourhood in Cancun. It’s beautiful, but muggings are a common occurrence, and wearing headphones is volunteering for one. I quickly came to love the peace and quiet. It’s nice to have some time to think.

Level 2 (Adding Medium Cardio)

When walking starts to feel easy, swap two of your walks for 20-minute rucks or jogs. This is when your cardio will really start to feel like cardio. It’s hard, and it hurts, so your body will flood you with endorphins to numb the pain. It feels almost like eating suicide wings.

Adding this medium cardio unlocks a slew of new benefits. For example, every extra MET you’re able to handle reduces your risk of heart disease by around 13% (study). So if you can gradually go from being able to tolerate a brisk walk (4 METs) to a slow jog (7 METs), that’s a 39% reduction in risk. And that’s just one of the many benefits. Getting fitter improves virtually every aspect of your health and performance.

Jogging is a great choice if your feet, shins, knees, and hips are ready for the extra impact. Rucking is a better choice if you want to ease into higher impact. Both are similarly effective and enjoyable. Both can easily get you above 7 METs.

Note that the impact from jogging is a good form of stress. You can adapt to it. Your bones will grow denser, your tendons will grow tougher, and the cartilage in your knees will grow stronger, reducing your risk of common issues like arthritis (study, study, study). You just need to make sure you can recover enough between sessions. That’s why it might help to start with rucking.

| Day | Workout |

|---|---|

| Monday | 20-minute jog or ruck |

| Tuesday | 20-minute walk |

| Wednesday | 20-minute jog or ruck |

| Thursday | 20-minute walk |

| Friday | 20-minute jog or ruck |

| Saturday | Rest |

| Sunday | 40-minute walk |

If you’re jogging (full jogging guide coming soon), jog as slowly and gently as you can. If it feels too hard, see if you can go slower. Switch to walking whenever you need to catch your breath. Jogging can feel extremely vigorous for beginners. Going from 4 METs to 7 METs is no small feat. Keep working at it until you can jog steadily for 20 minutes.

Notice that we recommend jogging for a specific amount of time, not at a specific pace or for a specific distance. Let your level of fitness decide how fast and far you run. Focus on surviving for 20 minutes before worrying about going faster.

If you’re rucking (full rucking guide here), start with 10 pounds. It won’t feel like much, but that’s okay. Walk as briskly as you can, and if you feel like you still have gas in the tank when you get back home, add another 5 pounds to your rucksack next time. Keep working at it until you’re rucking with 40–60 pounds.

Rucking is one of the simplest forms of cardio, but you need a bit of gear. A regular backpack loaded with books or bricks works fine at first, but once you pass around 15 pounds, you’ll want a proper rucksack. I bought a GR2 rucksack, a 30-pound weight plate, and a sand kettlebell from GoRuck (affiliate links). They make the best rucking gear.

The sand kettlebell is so you can gradually load your rucksack heavier. Once the sandbag gets up to 30 pounds, swap it with the plate, and start loading the sandbag up again. This setup will get you to 75 pounds of load, which is more than you’ll ever need.

We recommend rucking for a specific amount of time, not with a specific amount of weight. Let your strength endurance determine how much weight you carry.

- Bonus 1: gradually increase the time to 30–40 minutes.

- Bonus 2: add a third (or fourth) jog or ruck.

Level 3 (Adding Hard Cardio)

When you’re able to jog or ruck for 20–40 minutes, you can swap or add a high-intensity interval training (HIIT) workout. These HIIT workouts will improve your speed, power, and athleticism. Your aerobic capacity will improve at an even faster rate. You’ll notice gains in your jogging/rucking performance, too. We’ll give you some HIIT protocols in the HIIT section below.

You may need to increase the intensity and duration of your walks to keep them challenging. You could add a bit of weight or switch over to light jogs. You can also merge the walking sessions into one longer workout.

| Day | Workout |

|---|---|

| Monday | 20–40 minute jog or ruck |

| Tuesday | Rest |

| Wednesday | 20–40 minute jog or ruck |

| Thursday | Rest |

| Friday | 15-minute HIIT workout |

| Saturday | Rest |

| Sunday | 40–60 min light ruck or slow jog |

This gives you four cardio workouts per week. Most research shows that doing four cardio workouts per week is enough to maximize your rate of progress (study). You can make slower progress with three workouts. I suspect you can maintain your fitness with two, especially if you do other forms of physical activity (such as weight training).

You’re now doing a fully balanced cardio routine. This is how some of the best athletes in the world train. If you do some weight training on your rest days or in the afternoon, you’ve got a fully balanced exercise routine overall.

Progressive Overload for Cardio

You can increase your time, distance, or weight by as much as 10% per week. A 30-minute jog can become a 33-minute jog and then a 36-minute jog. A 20-pound ruck can become a 22-pound ruck.

If your performance is improving from week to week, you’re free to keep doing what’s already working. You don’t need to force progression when it’s coming naturally. There’s nothing wrong with staying at Level 1 or 2 for as long as you’re steadily making progress.

If your shins or joints hurt more than last week at the beginning of your workouts, you aren’t ready for more yet. You need to adapt to the stress before you add more of it. If you have little aches and pains, but they’re getting better every week, it’s okay to increase the stress a little, as long as the chronic pain keeps receding.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

What is HIIT?

High-intensity interval training is when you alternate between periods of intense effort (such as sprinting) and periods of lower effort (such as walking). The higher-internsity bursts provoke slightly different adaptations from steady-state cardio. For example, HIIT isn’t as good at stimulating the growth of new blood vessels, but it’s the most efficient way to improve VO2 max.

HIIT offers 3–4 unique benefits:

- HIIT is the most efficient form of cardio for improving VO2 max. If you’re doing less than an hour of cardio per week, you can get the most bang for your buck by doing HIIT. However, doing more cardio can improve your health and fitness even more.

- HIIT has a little bit in common with lifting weights. Going on short but intense sprints is somewhat similar to doing a 10-rep set of squats. You can build bigger muscles that way. Mind you, you’d build even bigger muscles by lifting weights.

- HIIT pairs well with other types of cardio. You’ll get the best health and fitness improvements by doing a mix of easy, medium, and hard cardio. The high-intensity parts of HIIT are hard cardio. They’re an important part of a balanced cardio program.

- HIIT might help reverse atherosclerosis. One study found that HIIT hacked away at arterial plaque (study). Walking doesn’t seem to be able to do that. It’s unclear if rucking or jogging would. We need more research before we can draw any clear conclusions.

You don’t need much HIIT to get great benefits. In the above study, 15 minutes of HIIT per week was enough to reduce arterial plaque. 15 minutes of HIIT is also enough to see robust improvements in fitness. All it takes is a few sprints per week.

HIIT Protocols

The first HIIT protocol is 3 minutes on and 3 off. You go as far and as fast as you can for 3 minutes and then rest for 3 minutes. That’s one rep. Start with 2 reps per workout and add a rep every week until you get to 4–5 reps. This is brutal but effective.

The second HIIT protocol is 1 minute on and 1 off. You go as hard as you can for a minute, then rest for a minute. That’s one rep. Start with 5 reps per workout and add a rep every week until you get to 10. This is a simple and popular approach.

The third HIIT protocol is high-resistance intervals. This protocol is great if you’re trying to improve at sports that require intense bursts of energy. You can sprint on flat ground, but hill sprints, bike sprints, and incline treadmill sprints are even better.

The goal is to push yourself as hard as you can for 3–8 seconds (getting your heart rate above 160 bpm). Then rest until your heart rate is back under control (130–160 bpm). That’s one rep. Start with 10 reps and add a rep each workout, working your way up to 20 reps per workout.

These workouts only take around 15 minutes. Start with one per week. Add a second if and when you’re ready for it.

Heart Rate

What is Heart Rate?

Your heart rate is how fast your heart is beating. The fitter you are, the slower your heart will beat while resting. The more intense your cardio workouts are, the faster your heart will beat while exercising.

The first step is to calculate your maximum heart rate. From there, we can break it down into different zones. This calculator uses the best algorithm, but it’s still just a rough estimation. There’s genetic variation in maximum heart rate.

Heart Rate Calculator

Don’t worry too much about your heart rate. These estimations aren’t that accurate, and everyone’s zones are a bit different. For example, that calculation puts my max heart rate at 185, but my real max heart rate is 205. That’s okay, though. As a beginner, it doesn’t matter very much what your heart rate is. Just do your easy cardio at a conversational pace, breathing through your nose.

Once you’re good at cardio, you can do a stress test to find your true max heart rate. You can do that by sprinting until your heart rate hits its limit. You need to get pretty good at hard cardio before that, though.

Do You Need to Track Your Heart Rate?

You don’t have to track your heart rate while doing cardio. I didn’t during my first year. I think I should have, though, and I regret not doing it. Easy, medium, and hard cardio all correspond with heart rate zones, and it’s important to get into those zones to get the benefits.

If you decide not to track your heart rate (yet), you can listen to your body instead. When you’re doing easy cardio, you should be able to talk in full sentences, but it should feel uncomfortable. When you’re doing medium cardio, you won’t be able to talk in full sentences, but you should be able to breathe through your nose most of the time. When you’re doing hard cardio, you’re going all out.

How to Track Your Heart Rate

The easiest way to track your heart rate is to wear a fitness watch. Most of them are quite accurate, and many of them come with other handy features. After a year of doing cardio, I bought a Polar Ignite watch that tracks my heart rate, time, distance, and pace. (That’s an affiliate link to Rogue Fitness, my favourite fitness retailer.)

Note that the heart rate sensors that you strap around your chest (like this one) are even more accurate. I have a chest strap, but it’s overkill for me, and I rarely use it. The watches are more than accurate enough, and they’re far easier and more comfortable to use.

What Heart Rate Should You Train At?

Your maximum heart rate is the upper limit of what your cardiovascular system can handle during exercise. You might get close to that upper limit if you threw your entire soul into an all-out sprint, but most of your cardio will be done at a percentage of your max heart rate.

- Easy cardio: 60–75% of max heart rate

- Medium cardio: 75–90% of max heart rate

- Hard cardio: 90%+ of max heart rate

Training at these different percentages offers different benefits. A robust cardio program takes advantage of all of those zones, getting you all the benefits.

What’s a Good Resting Heart Rate?

A slower heart rate shows that your cardiorespiratory system is working more efficiently, requiring fewer pumps of your heart to fuel your body. Resting heart rate typically ranges between 55–100 beats per minute. It’s much better to be at the lower end of that range.

- 100 is common for sedentary people. These are the people who need cardio the most.

- 85 beats per minute is okay for seniors. However, it’s usually better to bring it even lower.

- 60 beats per minute (or less) is fantastic. If you’re young or middle-aged, this makes for a great long-term goal. Some athletes dip into the 40s.

One of Marco’s jobs as a strength and conditioning coach was to get his clients’ heart rates under 60 beats per minute as quickly as possible. It certainly worked for me. After a year of doing cardio, my resting heart rate now dips as low as 47 bpm.

To test your resting heart rate, laze around in bed for a couple of minutes after waking up. Track your heart rate while you lie there to see what pace your heart idles at.

Note: your watch can probably track your heart rate while you sleep. However, that technology is still new, so it’s unclear what the ideal sleeping heart rate is. Still, you can track it over time. You should see it going down as you get fitter.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Lifting Weights Count as Cardio?

Lifting weights burns through the fuel (ATP) in your muscles. When you finish a hard set, you’ll notice your heart rate is higher, and your breathing is ragged. That’s because your aerobic system is using the air you’re breathing to replenish the fuel in your muscles. This elevated heart rate can feel similar to doing cardio, and so a lot of lifters assume lifting will make them fitter.

Some studies show that lifting can improve cardiorespiratory fitness in young, untrained, out-of-shape people (study, study). Higher-rep hypertrophy training was better than lower-rep strength training. Doing supersets can help. But even then, the cardiovascular adaptations to weight training seem to taper off before you become fit. People who lift weights aren’t as out of shape, but they’re still somewhat out of shape.

Steady-state cardio causes your blood vessels to dilate, allowing blood to flow more easily. Your heart stretches wider, pumping more blood with every beat. Lifting weights causes your blood vessels to constrict and your heart to contract, allowing you to maintain a sturdier brace. Both cause great adaptations, but those adaptations are quite different.

By the same token, cardio isn’t good for building muscle (study, study). If you’re extremely weak and under-muscled, and if you’re eating enough food to support muscle growth, you can gain a little bit of muscle and strength from cardio, but not much. Hypertrophy training is far more effective.

How Should You Schedule Cardio with Weight Training?

Weight training and cardio provoke separate but complementary adaptations. You should include both in your routine. Mind you, if you aren’t doing either, you don’t need to start doing both at the same time. It’s okay to build these habits one by one. If you want help getting into lifting weights, here’s our beginner muscle-building program.

In an ideal world, you’d do your cardio and weight training as separate workouts (study). You could do cardio one day and weight training the next. Or maybe you do cardio in the morning and weight training after work. That way, both types of exercise build upon each other without interfering with one another (research breakdown).

In a pinch, it’s okay to do the workouts one after the other. There might be a small interference effect, but I doubt you’ll notice it, especially if your cardio workouts are relatively short (like we’ve outlined in this guide). If I fall behind schedule, I’ll lift weights, have a protein shake, and then head right out for a jog or ruck.

What’s VO2 max?

VO2 max is how researchers measure cardiorespiratory fitness. It’s the maximal amount of oxygen you can pump through your system. The more oxygen you can pump into your muscles while exercising, the better your performance will be. You’ll be able to run, swim, bike, and row faster for longer.

VO2 max usually declines with age, but you can reverse that trend. The average 20-year-old has a VO2 Max of 31–42 (study). That declines by around 7% with every passing decade, eventually dropping to 15–20 by 70 years old. However, VO2 max can be trained and maintained. 70-year-old athletes often have VO2 maxes over 50, easily outperforming relatively fit 20-year-olds.

You can measure your VO2 max if you want, but you don’t have to. If you’re gradually increasing the METs you can tolerate, you know your VO2 max is improving. If you go from walking to slowly jogging, and then you gradually get faster, you know you’re getting fitter.

What’s Zone 2 Cardio?

Zone 2 is part of the 5-Zone Model. It’s seeing a surge in popularity thanks to influencers like Dr. Peter Attia and Dr. Andrew Huberman. And that’s great. It’s an incredibly healthy form of cardio, it’s easy and enjoyable, and it makes for a great place to start.

Zone 1 is made up of casual physical activities like going on a stroll or working at a standing desk. Zone 2 is just beyond that, just hard enough to provoke an adaptation. So think of activities like going on a brisk walk or a slow bike ride. This is the type of cardio that gets you to around 60–75% of your max heart rate. You should be able to talk in full sentences, but you’ll need to struggle against heavier breathing to do it, making it somewhat unpleasant. We call it “easy cardio.”

Note that as you get fitter, Zone 2 gets increasingly vigorous. When you hear of endurance athletes training in Zone 2, they’re usually doing something like a slow jog for 1–2 hours.

Also note that guys like Dr. Peter Attia are getting their cardio recommendations from the coaches of endurance athletes (such as marathoners). This works best for people who are doing cardio for 10+ hours per week.

Marco’s expertise is in training rugby, soccer, and football players, so the training is more vigorous, focusing more on “medium cardio” at 75–90% of max heart rate. It’s quite a bit more efficient, provoking robust adaptations with as little as 2–3 hours of cardio per week.

Conclusion

Alright, that’s it for now. I really hope this guide helps. To start following it, all you need to do is start going on walks. That will give you a foundation strong enough to build upon.

If you have any questions, drop them below. I’ll answer all of them.

What about stair climbing for cardio? I enjoy that machine far more than the elliptical or treadmill and it seems to really get my heart rate up. also, what are your thoughts on energy drinks like bang or rockstar? Thanks Shane. I enjoy your articles.

My pleasure, Dave!

Stair climbing should be good. The trick is to make sure you can make it easy and hard enough. It could be that stair climbing is too hard to be easy cardio. I’m not sure. You might know better than me. Other than that potential issue, stair climbing is great. Incline treadmills are great, too.

I love energy drinks, but I try not to have them as part of my regular routine. I usually save them for when I’m working really hard on a specific goal. For example, if I’m doing a bench press specialization program, I’ll have an energy drink before my bench press workouts. I’m usually working on something, so I’ll often have a couple energy drinks per week.

I spoke with Danny Lennon, a sports nutritionist (who you might recognize from the Sigma Nutrition Podcast), about the health effects of energy drinks. He said that having a couple of them per week is totally fine, provided you’re active enough, you aren’t having more than 400mg of total caffeine per day, and you aren’t having them anywhere close to your bed time. Most energy drinks have 100–200 mg of caffeine, so I’d keep them at least 9 hours from your bed time. Same goes for pre-workout drinks.

Rockstar was a favourite of mine when I was living in Canada. Monster is more popular here in Mexico, and they have a special edition Day of the Dead mango flavour, so I’ve switched over. I’ve never tried Bang. I don’t think it’s available here.

Some studies show that caffeine can improve performance and reduce feelings of fatigue when doing cardio. Mind you, caffeine is also a vasoconstrictor and can increase heart rate. I haven’t personally found it to help. I don’t have energy drinks or coffee before my cardio workouts. I’ll usually have water, sometimes with a little chia, honey, and lime mixed in (and then leave it to set for 20 minutes before drinking). That’s a popular pre-workout drink for joggers here.

Thanks Shane for the detailed reply. Do you know if there is any difference considering joint impact with stair climbing versus jogging. Is it about the same? I don’t like running because it’s too hard on my knees and don’t wanna wear those out.

It’s hard to beat running for joint impact. I’d guess that stair climbing is substantially easier on your joints than running.

What wears out your knees is doing too much too soon, with too little recovery between sessions. If you can avoid that, impact is actually really good for your knees. The stress provokes an adaptation, and your cartilage will grow stronger, reducing knee pain and preventing arthritis.

Jogging might be too much right now, but if you wanted to jog, you could work up to it. You could start with shorter sessions less often. As your knees grow tougher, you could increase the dose.

I had a similar issue with my shins. My shins weren’t strong enough to jog, so I kept getting shin splints. I had to get more of my minutes from walking and rucking. It took a few months for me shins to grow strong enough to handle 20-minute jogs twice per week. Now I’m up to 30-minute jogs four times per week.

If you like the stair climber, I’d start there, though. And those things are tough! You can stick with that indefinitely. You may find your knees grow tough enough that you can experiment with jogging (if you want).

I’ll ping Marco to see what he thinks about the knees specifically with the stair climber.

Using the stairclimber will definitely be easier on the knees than jogging, and is a great way to get cardio in.

Like Shane said, you can condition yourself to jog without pain but it just takes a bit of time and patience.

Thanks so much for this article! And congratulations on making it to Level 3!!

I appreciate the 10%/week! I have heard and experienced that *most* running injuries don’t come from pavement impact, they come from increasing the mileage too fast. This seems like a great way to implement that!

Related to injuries though, do you have any recs for exercises to avoid running injuries? Perhaps the kind of thing that a physical therapist would recommend? I’ve seen the advice that if you have appropriate strength & range of motion then your gait will naturally converge to something good, but if you don’t, you could end up with “bad” or less efficient form. Right now I throw in exercises when I brush my teeth, either lateral motions with a band, balancing on 1 foot, or calf raises.

I’m also curious if you have thoughts on walk-running/walk-jogging, i.e., taking scheduled walk breaks *before* you get tired. There’s some discussion of it here https://www.nytimes.com/article/how-to-start-running.html. This is how I got started and I still do it just because I prefer how it feels. I can go for longer, and more of the run feels like a moderate effort, as opposed to an increasingly painful one. You get to run, which can feel more natural and athletic/fun than jogging super slowly. The walk:run ratio is a natural mechanism for progressive overload. Plus it’s also a nice way to spend time with someone who is in better shape than you (it can serve as their warmup, or their recovery day). There is something nice about running along side a friend or partner, even if briefly.

Some context: I’ve also been adding in more cardio over the past several years. I had gotten to a point where I was pretty satisfied with my muscle mass and gaining more wasn’t outweighing the annoyance of eating more. Over the past couple years I’ve just done maintenance lifting 3-4x / month. I do some form of cardio 3-6x/week.

Thank you, Aaron! My pleasure, man.

I think that’s the right way to think about running injuries, yeah. I run on the pavement. That can increase the stress on your shins, knees, and hips with every stride, but that isn’t inherently good or bad. Running on perfectly ideal running turf might help you survive more miles, but either way, it all comes down to stress, recovery, and adaptation. If you subject yourself to enough stress often enough, you’ll adapt, growing tougher. However, if you cause too much stress too often, you can get overuse injuries.

I agree that form tends to fix itself, especially with activities as natural as walking, jogging, and running. Think of toddlers experimenting with walking until they get it right. Cues and coaching still help, but putting in the practice is the most important.

Marco and I are working on a running article. We wanted to keep this article about cardio in general. The running article will talk about running gait and how to improve your form. Marco’s already filmed the tutorial video.

I think the Jeff Galloway version of the run-walk method is good, especially if you prefer it, and especially if you’re making good progress (or happily maintaining your progress). There are many great ways to do cardio. My only worry is that if it never feels hard and you never get tired, you might not be pushing yourself hard enough to provoke a robust adaptation.

It also sounds like you’re pushing above your anaerobic threshold and then resting to recover. If you ran at or below your anaerobic threshold, you’d be able to sustain your pace for much longer. I suspect that changes the category of cardio you’re doing. I’ll ping Marco to see what he thinks.

I used a different approach. I jogged as slowly as I could for as long as I could, lasting only a couple of minutes at first. It felt quite intense and left me gasping for air, almost like HIIT. When I caught my breath, I’d do it again. After 20 minutes, I’d call it a day and walk home. Now, I run for the full 30–40 minutes. When it starts feeling too hard, I remind myself that I can run slower, and I try to make it feel easier, but I keep running. I’m still not great at running, but I love being able to run for the entire stretch.

I love the idea of doing cardio with other people. I use rucking for that. I usually do that for my “easy” Zone 2 cardio so that I can maintain at least the semblance of a conversation while doing it.

Congrats on reaching your strength and muscularity goals! Your routine sounds perfect for maintaining your gains while making great cardio progress. Awesome 🙂

Hey Aaron!

For the walk/run method, like anything it has it’s pros and cons.

For people learning to run it is an excellent method because it prioritizes running with less fatigue, so the new runner is less likely to get an overuse injury.

For your easier cardio training where you’re not trying to get your heart rate above a certain point it works well because it’s programming rest into your workout naturally. These lighter workouts can potentially be helpful for recovery as well as improve your heart’s efficiency with each stroke. This happens when you’re in the easier heart rate zone for a prolonged period of time. Your heart muscles adapt to lengthen more and are better able to take in more blood with each stroke. When you get to higher heart rates you start training more of its ability to pump more vigorously with each beat.

Like Shane said, it will have it’s limitations if you’re trying to improve speed or your tolerance of higher heart rate zones where you want to achieve fatigue and overload yourself so that you stimulate your body to adapt and become more capable. At the same time, when we coach weight training, we usually say to get to within 2 reps of failure, so not complete failure but you’re still going to be tired. I think running is similar, you don’t want to be so gassed where you’re way outside your zone of competence and risking damage/bad habits, but you do want to feel some challenge.

Or if you’re trying to train your lower zone it might interfere with that if you are running really fast then bringing your heart rate way down.

Either way I think the walk/run method can be modified to suit either an easier heart rate training day or a higher heart rate training day. So long as you use progressive overload principles you can make progress, but sometimes this might involve pushing harder on some workouts.

For the easier heart rate training you would run slower when running and take shorter walk breaks, so your heart rate stayed in a certain range.

For the higher heart rate training you would run faster to get the heart rate in a higher range and walk as necessary.

Oh, one more thing!

I think I might be a “fast HR” person. I can do a jog with someone and we’ll have gone at the same speed, we’ll be comparably tired and breathing at the same pace, but my heart rate will be 10-20bpm higher than theirs.

You mentioned that there’s genetic variation in max HR. Is there a better way to calibrate those easy/medium/hard cardio categories? I try to go by “effort” but maybe that’s squishy and serving as an excuse to not workout hard enough?

Thanks so much!

Maximum heart rate is largely genetic, yeah. It’s okay if yours is naturally higher.

We’re working on an article about testing your maximum heart rate. It’s more of an intermediate method, once you start getting good at doing HIIT. You need to be able to push yourself to your limit to find out where that limit is.

You can calibrate the easy/medium/hard categories by paying attention to how it feels. You don’t need to track your heart rate. Here’s how to gauge your effort:

Easy is when you’re training just above your aerobic threshold. That means you can comfortably sustain the exercise with the air you breathe, steadily burning body fat for energy. You can keep up your pace for hours, but you’ll notice your heart beating a bit faster than normal, and talking will be uncomfortable. You can keep up a conversation, but you’ll need to pause to breathe between sentences, and you won’t be able to sing.

Medium is when you’re training just below your anaerobic threshold. This is a pace you can sustain for 20–40 minutes. It’s characterized by just barely being able to get enough air to fuel your workout. You’ll be able to say a word or two, but no more. You might have trouble getting enough air through your nose, forcing you to breathe through your mouth.

Hard is when you cross your anaerobic threshold. This is when the air you breathe isn’t enough to sustain your exercise, forcing you to rely more on the glucose. You won’t be able to talk at all. You might not even breathe very much. You might find yourself holding your breath for a few seconds at a time. Imagine doing a 10-rep sets of squats or deadlifts, or running up a hill. As you near the end, your muscles might burn. When you stop, you’ll be left gasping for air, heard thudding against your ribs.

You can track your fitness improvements by measuring your resting heart rate. You’d measure your heart rate in the 1–2 minutes after waking up, while you’re still lying in bed. See if you can get that number lower, ideally eventually getting it below 60 bpm, and perhaps even under 55.

Thanks for the ranges of healthy resting heart rates during the day. Could you give the same ranges for heart rates during sleep?

What would be common for sedentary people, okay, and fantastic during sleep?

Hey Alexander. Having a lower resting heart rate is good while sleeping, too (study), but it hasn’t been studied nearly as extensively as resting heart rate while awake. That’s where all the tradition and research is, so that’s what I’d use.

I don’t want to make guesses about what’s ideal. It’s not something I’m familiar with. If you track your heart rate while sleeping, though, you could keep a note of it. After following a cardio program for a few months, make another note of it. See if it’s gone down. If it goes down, that hints at an improvement in fitness.

I’m sorry I can’t give you a better answer. I’ll keep an eye out for information on heart rate while sleeping. If it winds up looking promising, I can write an article about it.

Hi Shane and Marco, great article, very easy to understand and implement. I have a question of how I would incorporate a cardio programme for myself using this information. I already have a decent vo2 max in the mid 50s and a resting heart rate in the 40s as I play soccer competitively and somewhat regularly. I also lift weights 3 x per week as you suggest, and I play soccer 2-3 x per week depending on circumstance, its normally 1 or 2 vigorous hour long training sessions, and one 90 minute match. Sometimes its 2 training sessions depending on time of season but right now its only one.

What would be an optimal routine for someone with this schedule to take care of their health and enhance performance. Thanks 🙂

Hey Nick, it sounds like you’re already doing great! Soccer is fantastic for improving your cardiorespiratory fitness, and lifting weights is giving you even more stimulation, even if that stimulation isn’t quite ideal for cardio. That gives you all the volume and intensity you need for great general health and fitness.

Depending on how high your heart rate gets while playing soccer, it would count as medium or hard cardio. Maybe both. So the main thing you’re missing (from a health and longevity perspective) might be a longer easier workout. Something like a long brisk walk, light ruck, or casual jog. I suspect that would give you the stimulus you need to push your VO2 max higher and maybe drop your resting heart rate a bit lower. You don’t necessarily need that, though. You’re already quite fit.

If you wanted to improve your conditioning for soccer, your training sessions might already be designed for that, I’m not sure. If you wanted to improve your performance, your conditioning would be more specific to your sport. You could build endurance in the specific muscles you need. Maybe do more explosive HIIT (doing very short sprints). Maybe add more unilateral leg exercises to your weight training workouts (if you aren’t doing that already). We could also work on improving other relevant metrics, such as your heart rate recovery (HRR). That way you’d be able to do bursts of intensity more often.

You’re far beyond a beginner, though. I think you’d benefit from a more advanced article/program. Marco and I are working on that. Stay tuned!

Hi,

what is the very minimum cardio to optimize performance at weightlifting (e.g. reducing rest times, improving at high-reps lift)?

Since I am still bulking (10 kg so far), I would postpone complete cardio (150 min) at a later stage. I am thinking of doing 30 min of easy cardio per week, and gradually increase intensity until HIIT.

Thanks for the informative posts.

Looking forward to the jogging guide!

Hey Rob,

If you want to fully optimize performance, I’m not sure there’s a ceiling. Being fitter is better.

But you can probably get the bulk of the benefits with relatively little cardio, especially if you’re also pushing yourself at the things you want to get better at: trying gradually shorter rest times, trying higher-rep sets, doing more supersets.

30 minutes of easy cardio per week isn’t very much, but it’s a great place to start, and you can always increase it later. And, as you gradually increase the intensity, you’ll get more bang for you buck. You don’t need to improve at everything all at once. It’s okay to start with cardio OR lifting. You’d be doing better than that.

I’m just starting to get in more cardio than just walking, and finding it feels really good after a couple years of lifting/bulking. You touched a bit on Zone 2, but I’m wondering if you can tie the other “zones” to your cardio definitions. For example, would Zones 3-4 be “medium cardio” and Zone 5 “hard”? My Apple Watch makes it easy to see how many minutes I’m spending on each zone viewable by weeks/months/etc. It would be convenient to use these as a guide as I start to incorporate more cardio.

Thanks!

Hey TW, that’s awesome. How are you finding your energy levels?

I hear you. My fitness watch is the same.

That’s right, yeah. Zones 3–4 are medium cardio. Zone 5 is hard cardio.

Note that easy cardio works best during exercise that lets your blood vessels dilate and also when you do it in bigger chunks. Weight training might get you quite a few minutes in that zone, but you’re under tension and it’s intermittent, so the adaptation is different. It helps to intentionally set aside 45–90 minutes for a long walk, jog, or bike ride, really pushing the endurance side of it.

Good luck!