Concurrent Training: How to Schedule Cardio & Weight Training

In this article, we’ll teach you how to improve your cardiovascular fitness while building muscle and getting stronger. We want the health benefits of doing cardio, but we aren’t trying to lose weight. We’re trying to build muscle. That changes things.

- You need to schedule your cardio and muscle-building workouts. That means you’ll need to schedule your cardio somewhat carefully. Otherwise, the so-called “interference effect” can interfere with the muscle-building adaptations you get from lifting weights. Some people downplay this effect, but some research shows it can cut your rate of muscle growth in half (study).

- Lifting weights improves cardiovascular fitness. Lifting isn’t ideal for improving cardiovascular fitness, but it’s not too bad. If you lift weights, you’re probably in significantly better shape than the average person.

- If you’re trying to build muscle, you’ll have different questions about cardio. What type of cardio should you do while bulking? Will doing cardio help you build muscle more leanly? Can weight training count as cardio? How can you maximize cardiovascular and muscle-building adaptations at the same time?

- What is Cardio?

- How to Exercise for General Health

- Resistance Training Recommendations

- How to Make Lifting Even Better for Your Heart

- What Counts as Cardio?

- Types of Cardio Sorted by Intensity

- Should You do Traditional Cardio or HIIT?

- The Best Type of Cardio to Pair with Lifting

- How to Avoid the Interference Effect

- Progressive Overload for Cardio

- The Best Muscle-Building & Cardio Routine

What is Cardio?

Living a healthy lifestyle will improve your cardiovascular health. You can eat a good diet, get enough sleep, lift weights, manage stress, and maintain a healthy body composition. You can also improve your cardiovascular fitness.

Your cardiovascular (or cardiorespiratory) fitness is your ability to convert the air you breathe into energy. This is your VO₂ max: the Maximum Volume of Oxygen you can consume during exercise. The more energy you can produce, the fitter you are.

“Cardio” is short for cardiovascular or cardiorespiratory exercise. “Cardio” refers to your heart. “Vascular” refers to your blood vessels. “Respiratory” refers to your respiratory system. All of this refers to breathing in air, converting it to energy, and delivering that energy throughout your body.

Cardiovascular exercise is anything that gets your heart rate high enough to improve your cardiovascular fitness. When you do cardio, your body adapts by buffing up your heart and building new blood vessels, improving your ability to consume energy.

Cardio and aerobics aren’t quite the same thing. “Aerobics” means “with oxygen.” It refers to exercise where your muscles need a steady supply of oxygen. Think of brisk walks or slow jogs. Cardio is broader than that. Anaerobic “without oxygen” exercise can be good for improving your cardiovascular fitness, too. A popular example of anaerobic cardio is high-intensity interval training (HIIT), where you sprint and then rest. We’ll talk more about that in a moment.

A fitter cardiovascular system produces energy more efficiently, reducing your resting heart rate and allowing you to engage in more vigorous exercise more easily. Being cardiovascularly fit is also incredible for your health, longevity, energy, and mood (study). Even if you only care about building muscle, being fitter will improve your ability to build muscle. As such, cardio is a crucial part of a healthy lifestyle.

How to Exercise for General Health

Most health institutions, researchers, and experts recommend getting at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise per week and doing at least two resistance-training workouts (study, Harvard). That will improve both your cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health, giving you the full package: plenty of blood vessels, an athletic heart, bigger muscles, stronger tendons, denser bones, fewer health issues, and a longer lifespan (study, study). You’ll also look better. And younger.

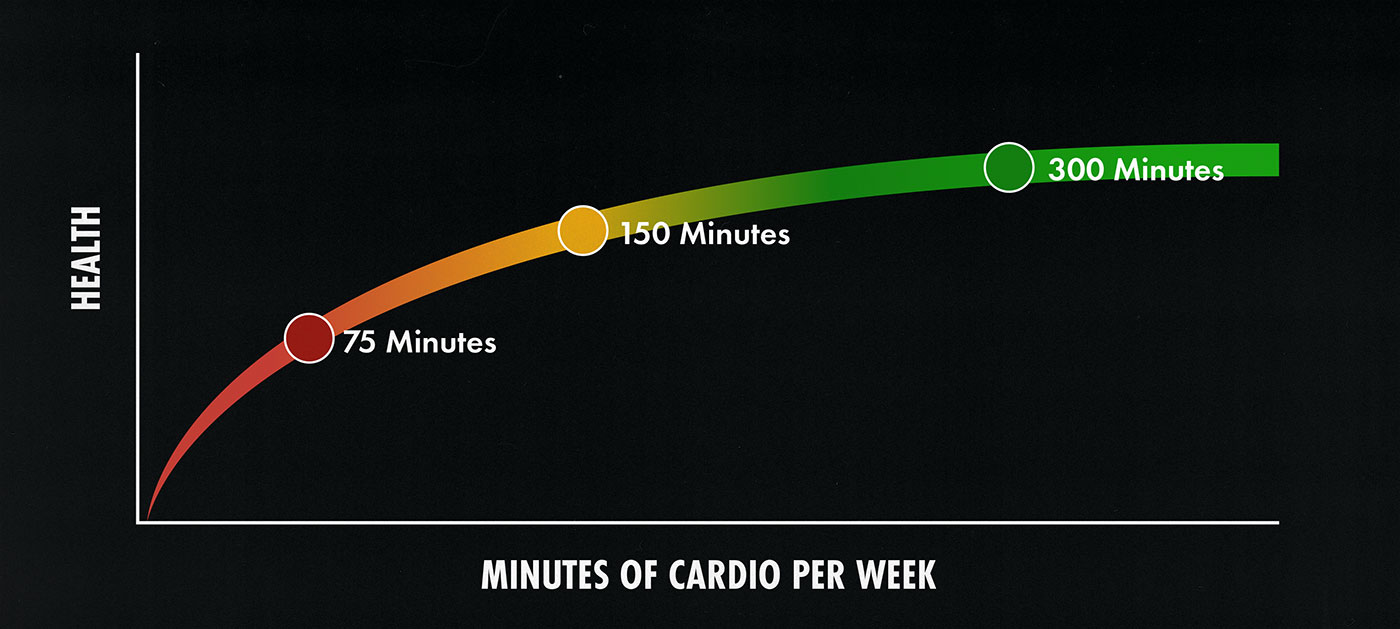

That range of 150–300 minutes isn’t a limit; it’s a point of steeply diminishing returns. If you do 150 minutes of cardio per week, you might get 75% of the benefits. By the time you get to 300 minutes, you might be getting 95% of the benefits. Bringing that up to 600 minutes might bring you to 98%. So although more exercise tends to be better, the return on the extra investment starts to drop quite low.

The good news is that if you’re just getting started, there’s plenty of low-hanging fruit to devour. You can get most of the health benefits with as little as 150 minutes of easy cardiovascular exercise per week. That’s only 21 minutes of walking per day. When that becomes too easy to challenge you, you can increase the intensity and length of your excursions.

The other good news is that you don’t need to worry about overdoing it if you’re naturally active. If you work a manual labour job and lift weights and play soccer, you’ll be even healthier than someone doing 300 minutes of exercise every week. Not much healthier, but healthier nonetheless.

Resistance Training Recommendations

You should do at least two resistance-training workouts along with your 150–300 minutes of cardiovascular exercise. Resistance training isn’t just good for your muscles and bones; it’s also good for your cardiovascular health. But resistance training and cardio improve your heart health in different ways. The benefits are complementary. If you can, you should do both.

Cardio is designed to improve your cardiovascular fitness, improving your ability to consume oxygen. Some types of resistance training are better for cardiovascular fitness than others, and some may even count as cardiovascular exercise. Circuit training is proving to be quite good for improving cardiovascular fitness. We can make guesses at the effectiveness of other types of resistance training:

- Circuit training (including kettlebell routines, CrossFit, P90X, and Insanity) is resistance training that’s specifically designed to improve cardiovascular fitness. It usually pairs a few different lifts together in a circuit, using very short rest times between each lift, keeping your heart rate high throughout the entire workout. It’s mediocre for building muscle and gaining strength but fantastic for improving cardiovascular fitness (study). An hour of circuit training counts as an hour of vigorous cardiovascular training.

- Callisthenics (including gymnastics) focuses on bodyweight exercises like push-ups, chin-ups, muscle-ups, planks, and jump squats. It can be great for cardiovascular health, especially if you focus on the bigger exercises and keep your rest times relatively short. It isn’t technically cardiovascular exercise, though, and it doesn’t seem to improve your cardiovascular fitness as much as traditional cardio training. An hour of callisthenics might count as about half an hour of cardiovascular training.

- Hypertrophy Training (including Bodybuilding) is designed to stimulate muscle growth. It usually includes weight training with barbells, dumbbells, exercise machines, cable stacks, your own body weight, and whatever works best for building muscle. It’s usually done in a moderate rep range of about 5–30 repetitions per set. Focusing on the bigger exercises and keeping the rest times relatively short is about as good as callisthenics for improving your heart health. An hour of hypertrophy might count as about half an hour of cardiovascular training.

- Strength training (including powerlifting) is designed to improve maximal strength. It usually focuses on bigger barbell lifts like the back squat, barbell bench press, and deadlift. It’s usually done in a lower rep range, with about 1–6 repetitions per set. The rest times are typically long, ranging from 5–10 minutes between sets. It’s fantastic for building denser bones and okay for stimulating muscle growth, but it’s not so good for cardio. There are too few reps per set, and the rest times are too long. It’s too sparse. An hour of strength training might count as a quarter of an hour of cardiovascular training.

All types of resistance training are good for your muscles, bones, tendons, and body composition. You can pick whatever type you prefer. If you want a default, go with hypertrophy training. It’s incredibly safe, amazing for building muscle, great for your bones, and good for your cardiovascular health. Even better if you use relatively short rest times and pair the exercises together into supersets or giant sets.

It’s possible that once you become fit enough to lift weights, your fitness adaptations will plateau, even as your muscles continue growing bigger and stronger. You’ll be quite a bit fitter than the average person, but you won’t be as fit as someone who does cardio (study). That higher baseline of fitness should be enough to get most but not all of the benefits of being in good shape. That means that if you want to maximize your cardiovascular health and fitness, you should do cardio, too.

How to Make Lifting Even Better for Your Heart

Lifting weights can count as light, moderate, or high-intensity exercise. It all depends on how much muscle mass you’re working, how hard you’re pushing yourself, and how long you’re resting between sets. That doesn’t mean lifting will provide the same benefits as dedicated cardio, but even so, it can be great for your general health and fitness.

Here’s how to lift for heart health without sacrificing any muscle growth:

- Get bigger and stronger. The more weight you lift and the more muscle mass you work, the more overall work you’ll do, and the better it will be for your cardiovascular system. Having more muscle and strength is healthy in many other ways, too.

- Do your bigger exercises as supersets. Doing big compound exercises engages a ton of muscle mass. Think of lifts like squats, bench presses, push-ups, chin-ups, deadlifts, and rows. If you choose a challenging weight and bring your sets close to failure, you’ll do a great job of building muscle while improving your heart health. Even better if you pair your exercises together into supersets. For example, you could do a set of squats, rest 1–2 minutes, do a set of push-ups, rest for another 1–2 minutes, and then go back to your squats. That way, your muscles get the ideal amount of rest for muscle growth, and your heart might still get enough stimulation to provoke cardiovascular adaptations.

- Do your smaller exercises as giant sets. Training your abs and arms doesn’t engage much muscle mass. It probably won’t provoke a cardiovascular adaptation. But if you combine the exercises into a giant set, you can get your heart rate much higher. You could do a set of biceps curls, rest 20 seconds, do a set of triceps extensions, rest 20 seconds, do a set of lateral raises, rest 20 seconds, and then repeat that “giant set” 2–3 more times. You’ll build just as much muscle, you’ll finish your workouts much faster, and you may do a better job of improving your general health and fitness.

- Use moderate-to-high repetition ranges. Higher rep ranges demand more of you. Doing a 5-rep set of squats is great, but you’ll do more total work and work your heart harder if you do a set of ten repetitions. Twenty repetitions might be even better for your heart, but at that point, your cardiovascular fitness might start limiting your lifting performance, preventing you from working your muscles as hard.

- Keep your rest times reasonable. If you aren’t doing supersets, giant sets, or circuits, try to start your next set when your breathing returns to normal. That way, your heart rate never fully settles back down between sets.

Remember that you don’t need to optimize your lifting for heart health. It’s okay to lift for muscle and strength. Powerlift as much as you want. You can improve your cardiovascular fitness with cardiovascular exercise.

What Counts as Cardio?

Cardiovascular exercise is anything that gets your heart rate high enough for long enough to improve your cardiovascular fitness. That can include walking, biking, lifting, yard work, and many different types of manual labour. To figure out how high your heart rate will get, you can look at the metabolic equivalent of the task (MET):

- Sedentary rest (1.5 METs or less): sitting at a desk, lounging on a couch, or reading. This is totally fine when you’re relaxing, but you shouldn’t always be relaxing.

- Light-intensity activity (1.6–3 METs): walking leisurely, working while standing, cooking dinner, or doing isolation exercises for your arms/delts/abs. Basically, anything more intense than sitting or lying down. Ideally, you’d be active for at least a couple of hours every day.

- Moderate-intensity exercise (3–6 METs): walking briskly, playing on the beach, casually lifting weights, powerlifting, playing with your kids, or carrying a kid around. People with active jobs or energetic kids often get enough moderate-intensity exercise without even trying.

- Vigorous exercise (6+ METs): rucking, jogging, circuit training, high-intensity interval training (HIIT), vigorous hypertrophy training, shovelling snow, playing sports, aerobics, and most other types of formal exercise. You only need 75–150 minutes of this every week.

To reiterate, you want to do at least 150–300 minutes of exercise every week. Lifting weights is good for your health, and it might count towards that total, but you should also do some exercise that’s specifically designed to improve your cardiovascular fitness.

Remember, it must provoke a cardiovascular adaptation to count as cardio. If you’re in bad shape, almost any form of physical activity will help. If you’re already in great shape, you’ll need more intense exercise to keep improving.

On the other hand, if you’re already in great shape, you don’t necessarily need to keep improving. It’s okay to exercise with the goal of maintaining a healthy degree of cardiovascular fitness. Sometimes great is good enough.

Types of Cardio Sorted by Intensity

It can be hard to know exactly how intense different forms of exercise are. For example, yoga and walking both seem like low-intensity forms of exercise, but yoga barely raises your heart rate, whereas going on a brisk walk can challenge your heart enough to provoke an adaptation. Yoga isn’t cardio. Walking is.

For another example, jogging might seem like “moderate” exercise. After all, it’s halfway between walking and running. However, most people jog without taking breaks, keeping their heart rates quite high. As a result, it does a great job of provoking robust cardiovascular adaptations. It counts as vigorous cardiovascular exercise. It’s fantastic.

Here’s a longer list of popular activities sorted by intensity level. Remember that higher intensity isn’t always better, especially if you aren’t in very good shape yet. More intense exercise can be more efficient, though, getting you similar benefits in less time. If you were only doing 150 minutes of exercise per week, better to train with the highest intensity you can manage.

Light-Intensity Activities

Light-intensity activity (1.6–3 METs) is part of a healthy, non-sedentary lifestyle. The more active you can be, the better it will be for your health. However, it doesn’t count as cardiovascular exercise. It includes activities like (reference):

- Standing while working/moving/fidgeting (1.8 METs).

- Yoga and stretching (2.3 METs).

- Walking at a leisurely pace (2.3 METs).

- Ab exercises (2.8 METs).

- Arm exercises like biceps curls (2.8 METs).

- Carrying a baby around (2–3 METs).

Moderate-Intensity Cardiovascular Exercise

Moderate-intensity exercise (3–6 METs) is fantastic for your health, and it absolutely counts as cardio. Moderate exercise includes activities like (reference):

- Pilates (3 METs).

- Briskly walking at an enjoyable pace (3.5 METs).

- Rowing/canoeing at an enjoyable pace (3.5 METs).

- Enthusiastically cleaning the house (3–4 METs).

- Yard work (4 METs).

- Manual labour like construction, farming, and carpentry (3–8 METs).

- Leisurely biking (3.5–6 METs).

- Actively playing with children (3.5–6 METs).

- Biking at a fast but comfortable pace (3.5–6 METs).

- Bodyweight exercises with plenty of rest (4 METs).

- Gymnastics (4 METs).

- Elliptical training (5 METs).

- Casually dancing (5 METs).

- Golf (5 METs).

High-Intensity Cardiovascular Exercise

High-intensity “vigorous” cardio (6+ METs) is amazing for your health. Some health experts say you can do 75–150 minutes of vigorous exercise per week instead of 150–300 minutes of moderate exercise (study). Vigorous exercise includes activities like (reference):

- Hypertrophy training (6 METs). However, since hypertrophy training is designed to provoke muscular adaptations, not cardiovascular ones, it’s debatable whether it actually counts as vigorous cardiovascular exercise. Most research shows that activities like hiking, jogging, and HIIT are better for improving cardiovascular fitness than hypertrophy training. Better to do a mix of both.

- Hiking (7 METs).

- Aerobics class (7 METs).

- Tennis (6–7 METs).

- Swimming laps (6–10 METs).

- Skating (7 METs).

- Skiing downhill (7 METs).

- Zumba (7 METs).

- Basketball (7–9 METs).

- Jogging (7–10 METs).

- Soccer/football (7–10 METs).

- Boxing (7–13 METs).

- HIIT (8 METs).

- Bodyweight exercise circuits with minimal rest (8 METs).

- Kettlebell conditioning circuits with minimal rest (8 METs).

- American Football (8 METs).

- Spin classes (8.5 METs).

- Walking up stairs (9 METs).

- Skiing cross-country (9 METs).

- Treading water (10 METs).

- Martial arts sparring (10 METs).

- Running (10–12 METs).

- Skipping rope (11 METs).

- Dragging a large carcass (11 METs).

- Sprinting (12–23 METs).

- Biking with maximum effort, either racing or uphill (10–16 METs).

- Running up stairs (15 METs).

Should You do Traditional Cardio or HIIT?

Traditional “steady-state” cardio has enjoyed a long reign as the dominant type of cardio. Most people still consider jogging to be the ultimate form of cardiovascular exercise. More recently, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has come into vogue. The benefits of HIIT are bold, numerous, and egregiously overstated. It’s gotten to the point where researchers have started publishing studies detailing all the popular misconceptions about HIIT (study).

Neither HIIT nor traditional cardio is ideal for building muscle (study). If you want to be strong, lean, and muscular, that’s what lifting and diet routines are for. Cardio isn’t very good for that stuff. It isn’t supposed to be. Cardio is for your cardiovascular health.

The one exception is that sedentary people store more fat in and around their organs, which is bad for their health. If you’re active, you’ll burn proportionally more of that fat, which is great for you. You can get those benefits from lifting weights, HIIT, or traditional cardio. All types of exercise are fantastic for getting fat away from your organs (study, study).

HIIT and traditional cardio are both amazing for your cardiovascular health. They can both raise your heart rate into the ideal zone. The difference is that HIIT raises your heart rate into the upper limits of that zone, allowing you to get similar health benefits with about half as much time spent exercising. Mind you, the benefits of HIIT aren’t necessarily quite the same as you get from traditional cardio. It’s a different intensity and duration of exercise. You may get synergistic benefits by doing a mix of both. But if we’re comparing one against the other, the health benefits seem to be similar.

Most people prefer traditional cardio. They’d rather go on a relaxing 30-minute walk outside than do an excruciatingly painful series of sprints up the stairwell for 15 minutes. You may very well be the exception, though. Some people love the ruggedly powerful feeling of exertion. That might be especially true of lifters. Especially the lifters who regularly squat and deadlift several plates.

Hypertrophy training has more in common with HIIT. A 30-second bike sprint followed by two minutes of rest is similar to a 10-rep set of squats followed by two minutes of rest. The bike sprints are designed to provoke cardiovascular adaptations, whereas the squats are designed to stimulate muscle growth. Each type of exercise is still specialized. But even so, they’re both anaerobic—without oxygen.

Recommendation: if you prefer high-intensity exercise, do HIIT. Otherwise, I recommend combining hypertrophy training with traditional cardio. That way, you’re doing anaerobic and aerobic exercise, arguably giving you more balance in your exercise routine.

The Best Type of Cardio to Pair with Lifting

Going on walks is the simplest way to add cardio to a muscle-building routine. If you go on a twenty-minute walk every day, that’s 150 minutes of cardio every week. If you walk for 40 minutes every day, that’s 300. Add in a couple of resistance training workouts, and you’re set. You’ll improve your cardiovascular and musculoskeletal health, giving you the best of both worlds.

Here’s why walking makes a great default:

- Most people find it quite enjoyable.

- You already know how to do it.

- It doesn’t sap much willpower.

- It’s easy to recover from.

- It’s incredibly healthy.

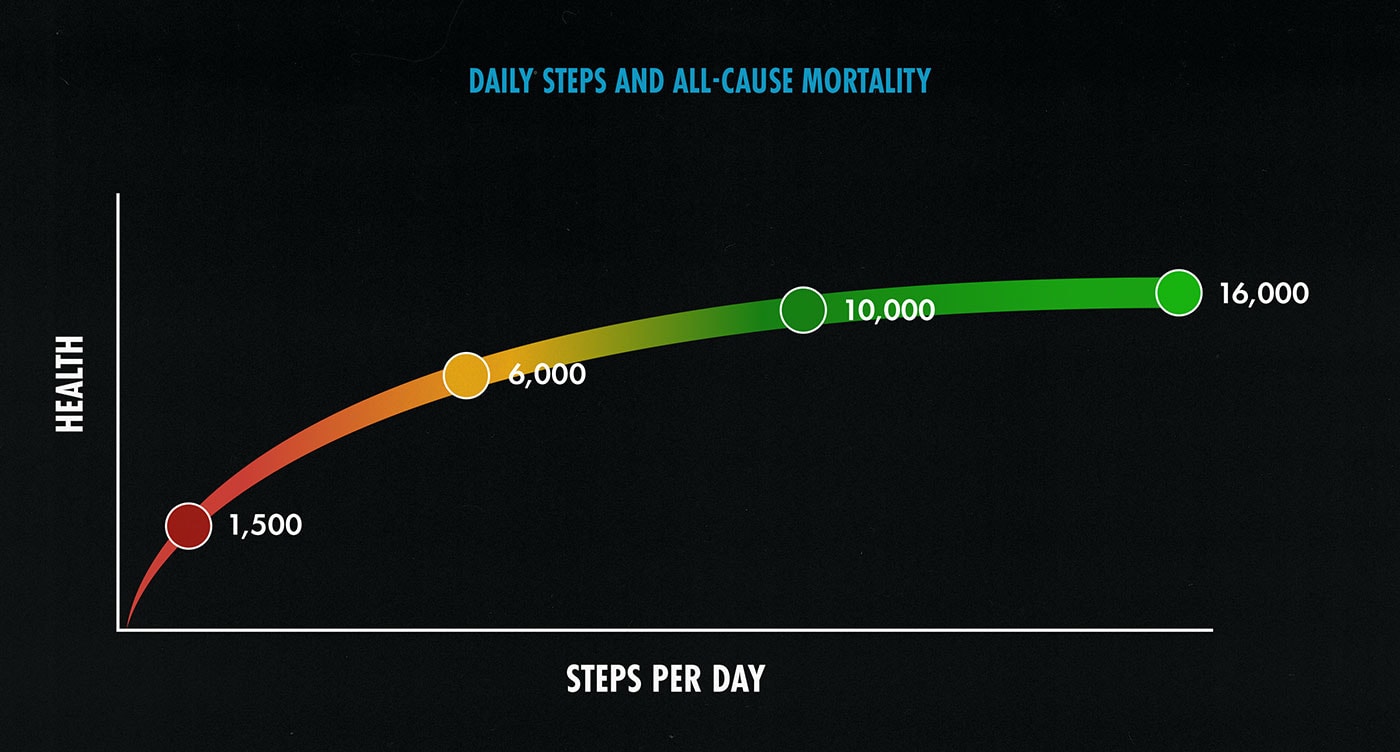

In fact, walking is one of the healthiest things you can do. The more steps you get per day, the longer you can expect to live and the more health benefits you can expect to enjoy (study).

If you want to kick your cardio into higher gear, you could try walking on an incline, jogging, using a stair climber, going hiking, going on bike rides, or doing high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

How to Avoid the Interference Effect

Resistance training and cardio don’t usually interfere with one another (meta). Hypertrophy training is great for stimulating muscle growth, and adding cardio may help. The blood flow adaptations might help you build more muscle in the long term (study). Similarly, cardio is great for getting fitter, and the strength benefits you get from weight training can help in the long term.

But you’ve got to do it properly. As a general rule of thumb, you want to separate your resistance training and cardio workouts. Here’s why: if you jog right after hypertrophy training (or vice versa), the strength and endurance adaptations might interfere with one another, with some studies finding that muscle growth was cut in half (study).

That study is somewhat of an outlier. Most research shows that you can pair cardio and weight training together without much trouble. Still, if you can avoid it, I wouldn’t train a muscle for muscle growth (e.g. squats) and then immediately train it for endurance (e.g. cycling).

If you can, I’d separate your workouts. I’d lift one day and do cardio the next. Or go for a run before work and lift after work. That will prevent interference between the two types of training, allowing you to get the best of both worlds (study).

Progressive Overload for Cardio

Progressive overload is just as important with cardio as weight training. To improve, you must make your cardio workouts more difficult. If you’re going on 30-minute walks, try to cover a little more distance every week. Another option is to start with 15-minute walks and work the time up, progressing in 5-minute increments all the way up to an hour. Or, if walking becomes too easy, you could kick it into higher gear, switching to jogging.

If you can go faster or further than you could before, that’s a great sign that you’re getting fitter. Keep trying to improve. And then, when you’re happy with your level of fitness, you can scale things back to maintain your results. Maybe you work up to three hour-long walks every week to get into better cardiovascular shape, then scale back to three half-hour walks to maintain that higher level of fitness.

If you’re trying to make your resistance-training workouts more vigorous, maybe you gradually work the rest times down, the rep ranges up, or gradually introduce more supersets and giant sets.

The Best Muscle-Building & Cardio Routine

If you want bigger muscles, denser bones, a more athletic heart, better blood flow, improved mood, great health, and a longer life, you could build an exercise routine something like this:

- Monday: 60-minute hypertrophy workout with supersets.

- Tuesday: 30-minute brisk walk

- Wednesday: 60-minute hypertrophy workout with supersets.

- Thursday: 30-minute brisk walk.

- Friday: 60-minute hypertrophy workout with supersets.

- Saturday: 30-minute brisk walk.

- Sunday: Playing with your kids, doing yard work, hiking, etc.

That gives you 180 minutes of vigorous resistance training and 90 minutes of moderate-intensity cardio. If you spend an hour or two on Sunday doing something active, this routine will give you 180 minutes of vigorous resistance training combined with 150–300 minutes of cardiovascular exercise. That’s enough exercise to optimize your cardiovascular fitness and maximize your rate of muscle growth.

The hypertrophy workouts would include big compound exercises done as supersets, smaller isolation exercises done as giant sets, relatively short rest times, and most sets would be done in a moderate rep range. This is how we program our workouts in the Bony to Beastly Program.

If you ever want to kick your cardio into higher gear, you could switch from walking to jogging, take up a sport, or start taking martial arts classes. That’s especially important if your resistance-training workouts aren’t working your heart very hard.

Alright, that’s it for now. If you want more muscle-building information, we have a free muscle-building newsletter. If you want a full exercise, diet, and lifestyle program to help you build muscle and improve your cardiovascular health, check out our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or our Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. Or, if you’re already an intermediate lifter, check out our customizable Outlift Intermediate Hypertrophy Program.

Hi Shane and Marco. Thank you for the article! I always appreciate your all’s take on things. I have two questions that immediately come to mind:

I spend a lot of time reviewing the MET compendium. How did you come to the 2.8 METs for the “Arm exercises like bicep curls”?

Also, I’ve been trying to find this answer for awhile, I’m curious what you guys think: Are vascular gains (e.g., capillarization, etc.) or even non-vasculaar gains (e.g., mitochondrial biogenesis) localized to the muscles used during the cardiovascular exercise modality performed? Would someone who jogs or cycles as their form of cardio not get the “improved blood flow to muscles, allowing them to build muscle faster in the future” to their upper body musculature?

Thank you again! I look forward to your all’s insight.

Hey Sam, good questions.

If you look at the MET compendium, you’ll see small exercises like crunches listed at 2.8 METs. You’ll also see “upper body exercises, arm ergometer” listed at 2.8 METs. This gives me the impression that small upper-body exercises like biceps curls, triceps extensions, and lateral raises are probably around 2.8 METs, at least for the average person. I hope that’s not too much of a stretch. Also, I could imagine that once you get strong at those arm exercises, they could be quite a bit more intense.

Your second question is easier to answer. Your assumption is correct. Vascular gains are specific to the area that you’re training. If you want more capillarization in your biceps, you shouldn’t go jogging, you should do high-rep sets of biceps curls (or shovel some snow, row, etc.). If you wanted balanced vascularization everywhere, you could do a higher-rep hypertrophy training routine, or you could do something like a full-body aerobics program.

This is a great article and really simplifies how to understand what cardio really is, what counts, and how to look at fitness more comprehensively. Probably one of my faves!

Thank you so much, Matt! 🙂

I love this, thanks so much!! Good motivation to get more walks into my day!

In the future if you have time to write or share thoughts on it, I’d be curious what you think about sprinting. I also got really into sprinting recently, as an adult. I’ve found that in my running group I’m one of the slower distance runners (~8-9min 5k), but I’m one of the fastest if not the fastest sprinter (~27-30sec / 200m). I assume that’s because I’ve been lifting at a beginner/intermediate level for many years. And when I do sprint, it feels like I just did a *killer* deadlift set. I’d be curious if other lifters have similar experiences, or if there are good exercises for getting quicker.

Plus it’s fun. Sprinting on a smooth track feels like an extreme sport to me in that you have to overcome your fear of falling/tripping and hurting yourself. You have to give yourself up to feeling unstable, or at best “stable in motion.” There’s a lack of control that reminds me of snowboarding.

Thank you, man! So glad you like it.

I’ve been lifting weights and walking for a while now, but I’m new to running. I’ve only just finished my first jog. My wife and I ran five kilometres at a comfortable pace, chatting as we went, and finished in about 30 minutes. Hearing that you can run 5k in 8–9 minutes seriously impressed me, so I looked up how long it should take. It looks like the world record is by Berihu Aregawi, running 5k in just under 13 minutes. Am I misreading something?

You’re right, yeah. Doing a challenging set of squats or deadlifts works your leg muscles in a very similar way to sprinting. Sprinters are known for lifting weights for exactly that reason. The two skills aid one another 🙂

Good stuff Shane! That is a very diggable and attainable weekly training schedule!

Woot! Thanks, man 🙂

Great article! I was wondering about how best to combine lifting with running when running is an important factor? Like training towards a 10k or half Marathon? Is it still possible to lift with a view to building muscle mass and strength whilst simultaneously building up towards one of these running distances? Or is the shear volume required for the running detrimental to the lifting in this instance? All the best, Ernst

Hey Ernst, good question!

If you’re training casually, aiming to make gradual improvements on both fronts, you’ll do fine. You might gain muscle a bit faster if you emphasize it more than running, and vice versa. If both have equal priority, though, you might be able to progress towards both goals at around 80% speed.

You’ll probably need to scale back the running and lifting a bit to make room for both. That’s okay. You can gain muscle just fine by training 2–3 days instead of 4–5 days per week. Same with running: scale it back to make it fit.

Also, if you’re new to either of these types of exercise, remember to ease into it. For example, if you aren’t in the habit of lifting weights, you’d start with two sets per exercise for the first week. Move up to 3 sets in the second week. Maybe add a fourth set to some exercises in the third week. Same deal with running: start slower and shorter, gradually increasing the speed and distance. That way you aren’t crippled with soreness after the first couple of workouts.

If you’re ALREADY in the habit of lifting and running, you’ll be able to handle much more. You’ll also have a better idea of how much you can handle. Just gradually rev it up.

Good luck, man! Sounds like you’ve got great goals 🙂

Thanks so much for your reply! Very helpful advice! Have a great year!

Would love to see a dumbbell version of the Outlift program for those of us that don’t have access to barbells.

That’s a great idea 🙂

If you haven’t tried it, you might like our Bony to Beastly Program. It’s built around dumbbell lifts, especially at first. We give a dumbbell alternative to every exercise, too. We made it with your situation in mind.

Hi Shane

I would say walking is likely to be a pretty easy, low intensity activity for most of your readers who tend toward the skinny side. When I was reading this article, I assumed by “cardio” you were talking about jogging, swimming, cycling etc until I read further.

Do you think a 30-minute walk following a resistance workout would really have an appreciable effect on hypertrophic adaptation? I would’ve thought you’d need to be doing something at jogging-level intensity (unless you were significantly overweight) for that. I’d think nothing of walking two hours in a day on which I do any strength training – and only worry about scheduling my running for non-resistance days. Is walking not a “free” cardio exercise in this case, as I thought?

I should add, I think your websites are fantastic!

Thanks for all the information and considered, balanced guidance you guys provide!

Hey Harry, good question.

Some of these studies on the interference effect looked at moderate-intensity exercise, such as going on a fairly casual bike ride. A brisk walk falls into that same category of moderate-intensity exercise, although on the lower end of it. Jogging counts as vigorous exercise, albeit on the lower end. I’d guess that walking doesn’t produce as much of an interference effect as more intense forms of cardio. I think your intuition there is probably right.

Separating your cardio and resistance training by six hours seems to prevent the interference effect. You don’t need to do your walking and resistance training on different days. You could go on a long walk after breakfast, lift at lunch, and then go on another walk after dinner. And with something casual like briskly walking, I wouldn’t be surprised if you could get away with less rest between the two different types of exercise.

I wouldn’t be surprised if going on a brisk 30-minute walk after a muscle-building workout slightly blunted muscle growth. You don’t necessarily need to care about that. It depends on whether you’re in the middle of a serious bulk or not. It depends on how much you care about absolutely maximising your hypertrophic adaptations. I’ve often walked to and from the gym, including during serious bulks. I still gained muscle without any issues 🙂

Also, keep in mind that “brisk” walking counts as cardio. You’d need to be walking fast enough to get your heart rate up. If you’re well-adapted to walking, the speed at which you normally walk might not challenge you very much. That might not interfere with your lifting as much, if it at all.

Hi Shane,

I’ve found even as someone who is well adapted to years of lifting and high intensity cardio (as a thing I do for fun, not necessarily for cardio gains), its still very easy to get caught out while trying to manage fatigue.

Would you ever say there is a point were it would be more beneficial to skip a weight session in favour of extra recovery? I lift 3x a week and train HIT cardio sports 2-4x a week. Say I know I’ve gone to hard on the cardio one night and slept terribly and know I’m not hitting any PRs in the gym that day… it better to take the hit on the weekly volume and prioritise recovery, or to just accept it will be a poor session? If the latter, how to you record it in your training notes?

• Do you record the reduced weight/reps and start back from there?

• Do you ignore the poor session, treat it as a micro deload and the next session try and pick up from pre-bad session?

• Should you try and pre-empt when this will happen, and move the weight session back a day to avoid?

• Is the only bad session the one that didn’t happen, or is this a myth the bros tell to scare children into being swole?

I’m guessing Marco gets this sort of thing a lot? With this much cardio, could it even be better to just weight train x2 days a week instead of trying to hit 3 days? Does he have his clients do this when strength &/or aesthetics isn’t their main goal? I’ve always been reluctant to do this for fear of leaving gains on the table, but am I potentially leaving the gains on the table now because I could be optimizing recovery better?

Are can you speed up recovery with something like a walk or is that BS? It doesn’t help that even when I’m tired and sore that I just don’t want to rest, so I’ll convince myself I need a ‘recovery session’ sometimes too where I just go light at either cardio or bring a deload week in early.. but at a certain point of fatigue can adding even recovery cardio just add more fatigue?

Hey Jason, good question.

I think it depends on your goals. If you’re trying to maintain your gains and focus on other things, I think it’s okay to take an extra recovery day, especially if your habit of exercising is locked in tight, and there’s no real chance of falling off the wagon. In your case, I think you’d be okay taking extra rest days when you need them.

If you’re trying to make progress, though, then you’d eat the poor workout. You’d grind through it, doing your best, and writing down what you’re able to do. This may stimulate some growth. More importantly, it will prevent the poor night’s sleep from negatively impacting your performance in the next workout. When you’re deciding how much to lift in that next workout, you’d ignore that subpar session. Go back to the workout before that one. See how much you were able to lift on a good day. So record the reduced performance, but ignore it going forward.

I think the “only bad session is the one that didn’t happen” is good advice for building habits and for when you’re doing a bonafide bulk. It’s not a myth. When you’re in a bad way, your body might break down some muscle. That isn’t the end of the world. You can rebuild it quickly. But it cuts into your progress. You’ll make steadier progress if you do the bad workout. That way your body won’t eat into your muscle. Training does a great job of counteracting the negative effects of poor sleep.

If your goal is to improve at cardio, yep, you could cut back on your lifting workouts. Put more of your effort into your primary goal. Dropping down to 2 lifting sessions per week is totally fine.

With his clients, Marco is pretty specific with goals. Maintain your overall progress, go hard at your main goal, making gradual progress at the thing you’re trying to improve at.

You could think of it like needing to pick up some groceries from two different stores. Don’t run towards both stores at the same time. You might not get anywhere. Better to grab the groceries from one store and then head to the next one. Once you have both bags, you can figure out where you want to go next. In the short term, that can mean lifting one day, doing cardio the next. When planning your training blocks, that can mean spending a few months on building muscle, maintaining cardio. Then spending a few months improving cardio, maintaining muscle. That’s often the best way to get the most gains, especially at your level, where gains are more difficult to come by.

I think recovery sessions are fine. Deloads can be valuable. You can always ease back on the secondary training if it’s interfering with your primary training. I’m focusing more on cardio right now than lifting. If my cardio session beat me up, I might go easier with the lifting. I won’t back down on the cardio unless I need a deload, though.

You’re already very active. I’m not sure if adding in extra walking would further boost recovery. That’s a good question. I don’t know. Walking is healthy and easy, and it does get blood flowing, and it absolutely helps more sedentary people. On the other hand, you’re already very active, and extra walks use up extra energy. How do the walks make you feel?

If you feel like you need a deload, and your scheduled deload is more than a week away, then you might be going a bit too hard overall.

Also, sometimes it takes a bit of time to adapt to a more active lifestyle. I’m not sure how long you’ve been doing all of this stuff all at once. Maybe in a couple months it will feel easier.

I’ve been doing it for a decade XD from B2B to present day, so I’m probably as adapted as I’ll ever be!

But that’s a good way to think about it.. its not always the same answer and it would change depending on training focus for the block.

Then I suppose the big thing is to pay more attention to training blocks and being strict on not over training the thing I’m supposed to be maintaining!

Man, that’s so cool.

Yeah, exactly. I have a single-track mind, so I have the opposite problem. As soon as I start striving for something new, I need to remind myself not to let everything else fall by the wayside. Either way, hard to find balance.