The Bent-Over Barbell Row Hypertrophy Guide

The barbell row, also known as the bent-over row, is one of the more popular compound lifts, and it’s commonly used in both strength training and bodybuilding programs. But most people don’t realize that powerlifters and bodybuilders do different variations of the barbell row. Even within bodybuilding, there are several different ways of doing them, with some designed to build a thicker back, some designed to build bigger biceps, and some designed to limit lower back stress.

In strength training routines, the barbell row is an assistance lift for the deadlift, used to strengthen the hips and lower back. In bodybuilding routines, the barbell row builds muscle in the upper back, spinal erectors, and forearms. Both styles of barbell row can be useful; both are great lifts. We’ll teach you the pros and cons of each.

The next thing to consider is how the barbell row compares against the dumbbell row and the t-bar row. Does the barbell row have any special advantages or disadvantages?

Finally, we’ll teach you how to do the barbell row properly, in a way that’s great for gaining both muscle size and strength.

What is the Bent-Over Barbell Row?

The bent-over barbell row is a compound lift used to strengthen the entire posterior chain, including both the hips and upper back. It’s popular in strength training and bodybuilding routines and has a great carryover to general strength, fitness, and athleticism. As a result, it’s often considered one of the foundational barbell lifts.

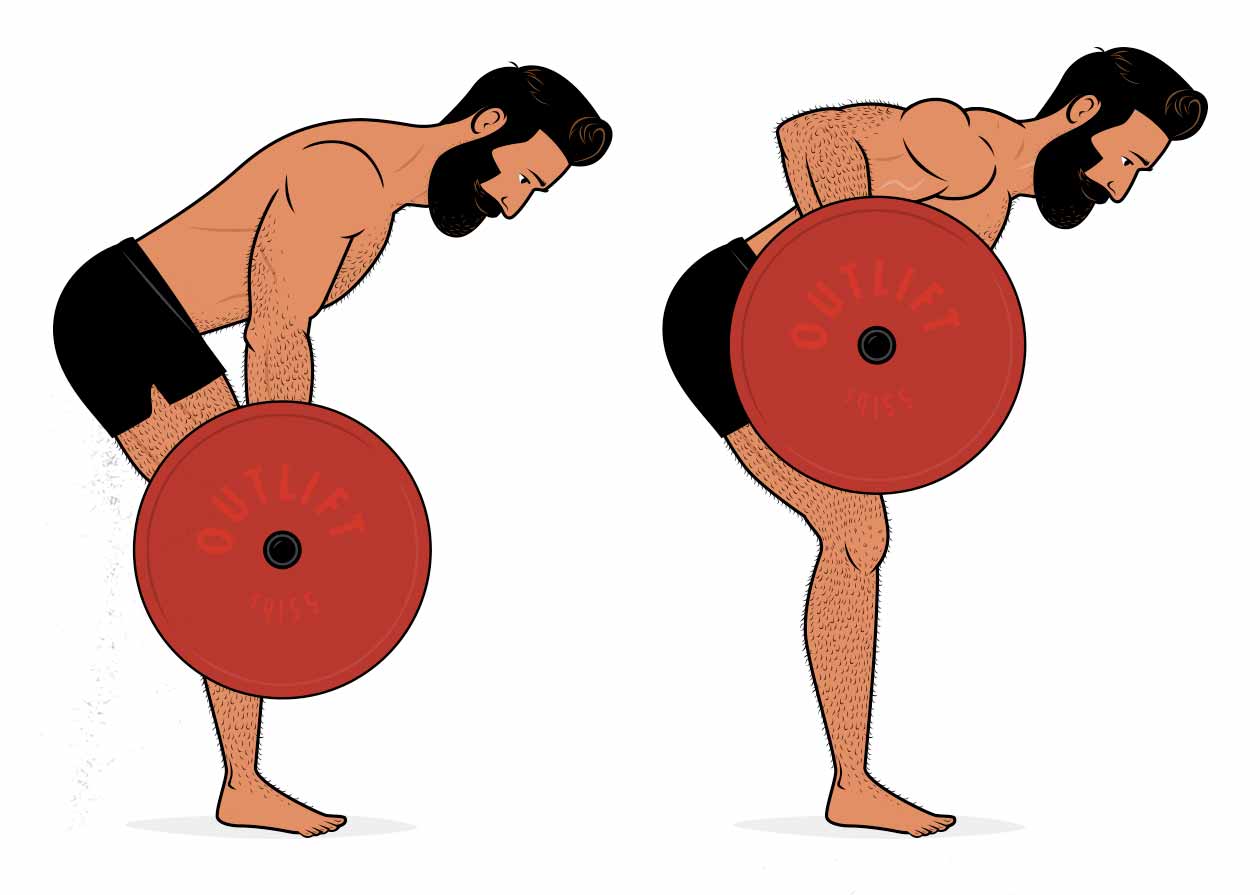

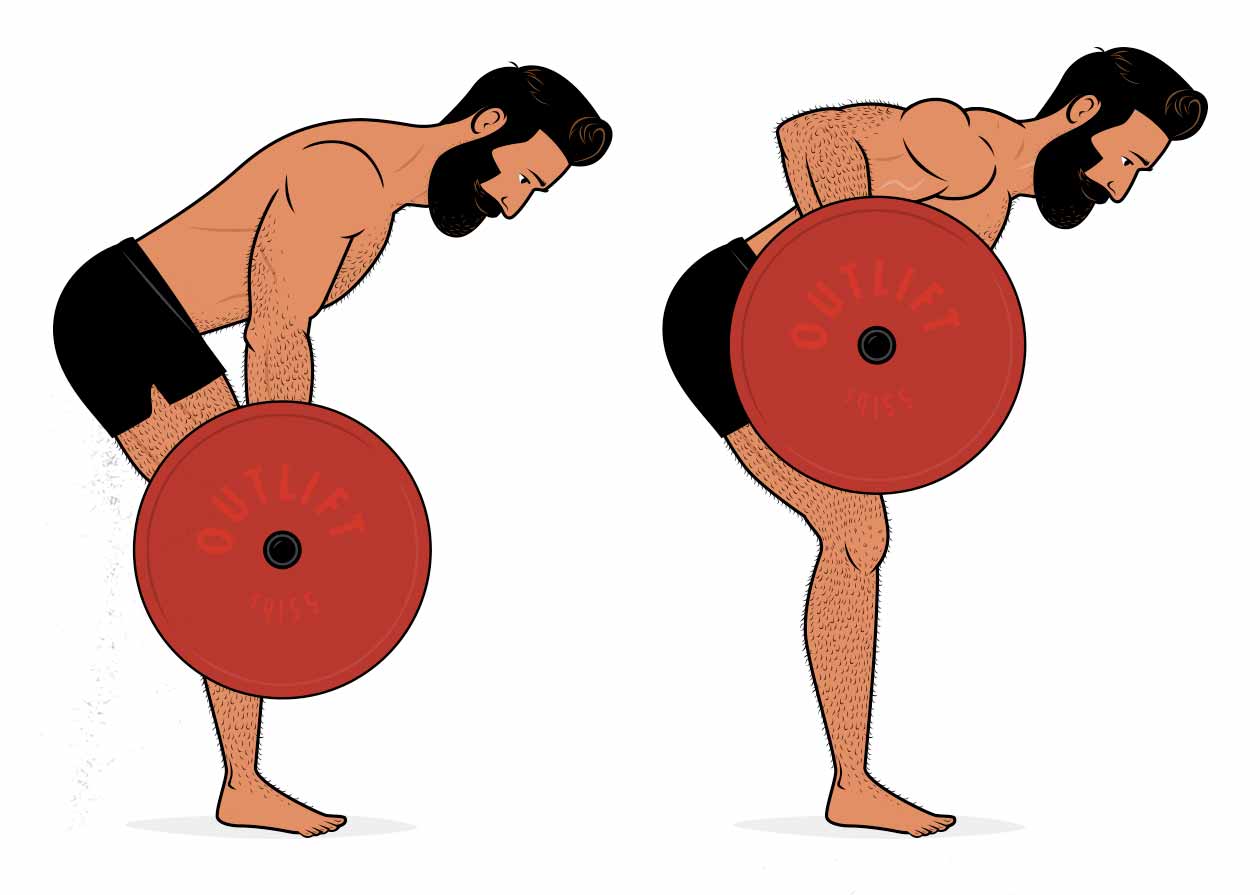

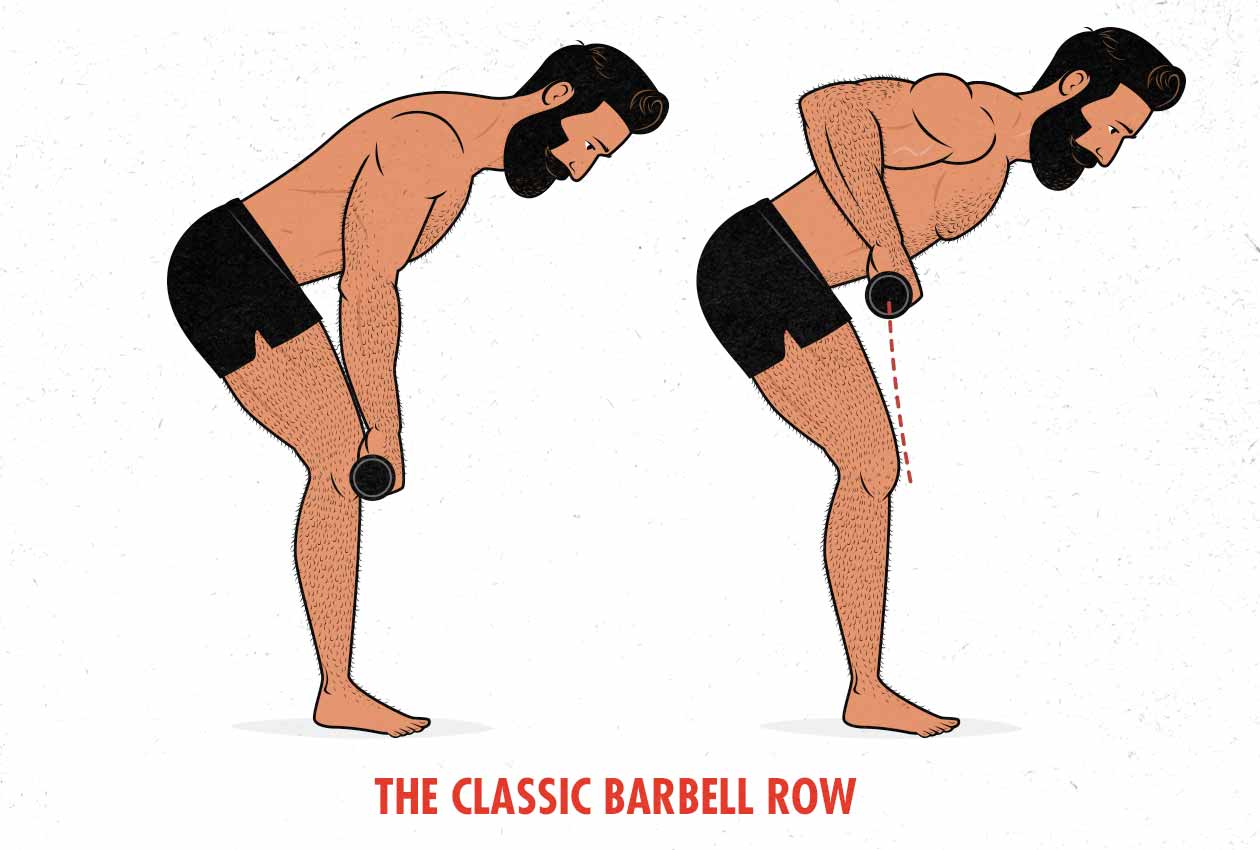

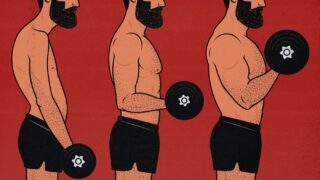

There are several ways to do the barbell row, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. When training to gain muscle mass, most people will start in a hip hinge position and row the barbell to their stomachs, like so:

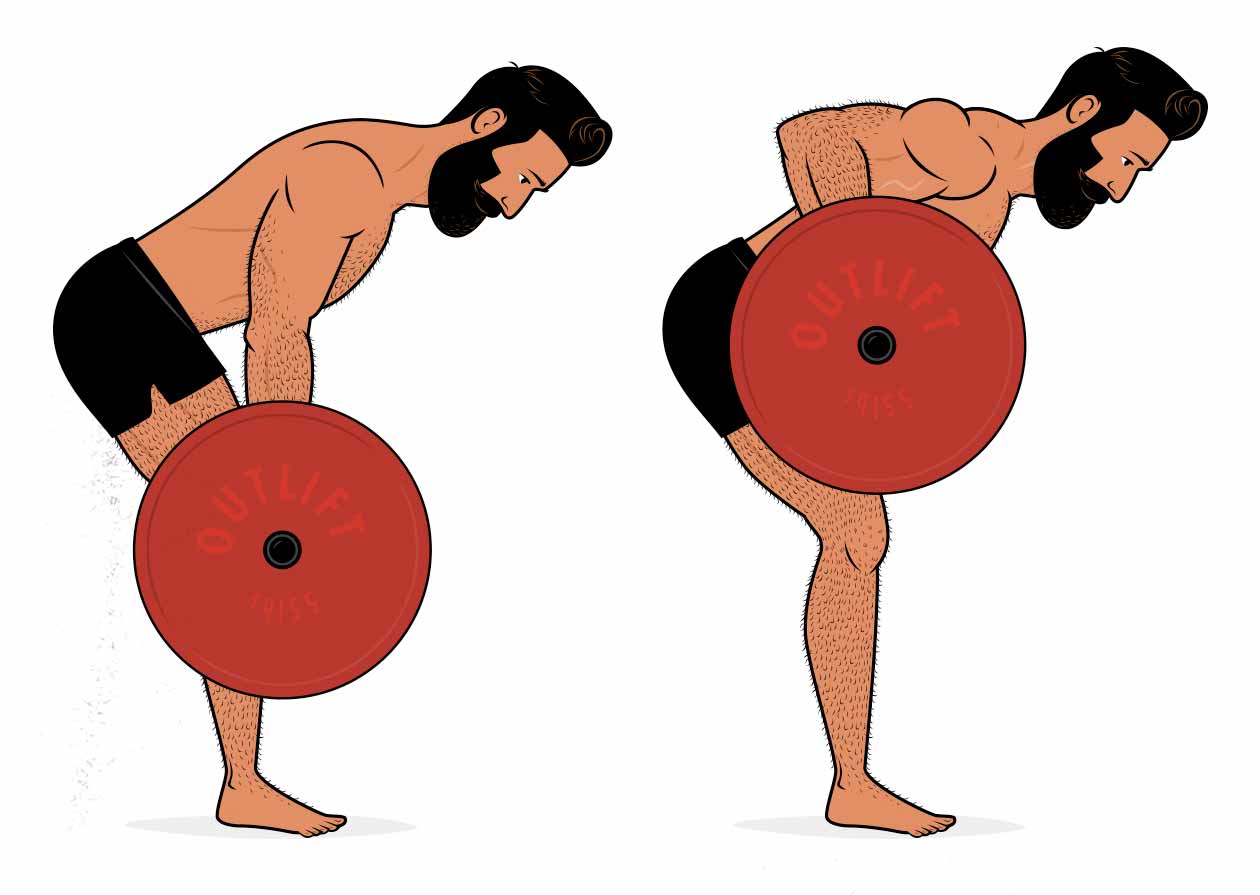

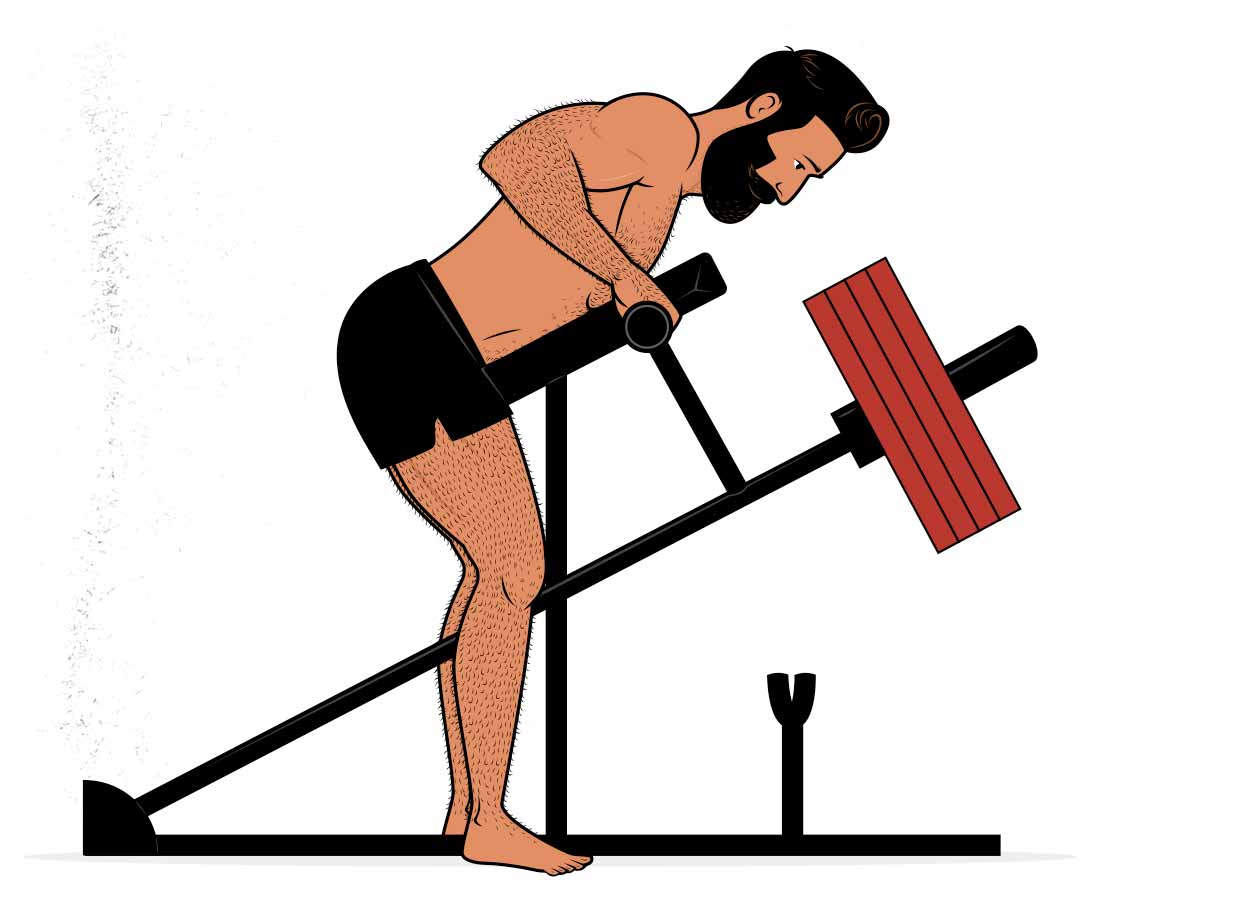

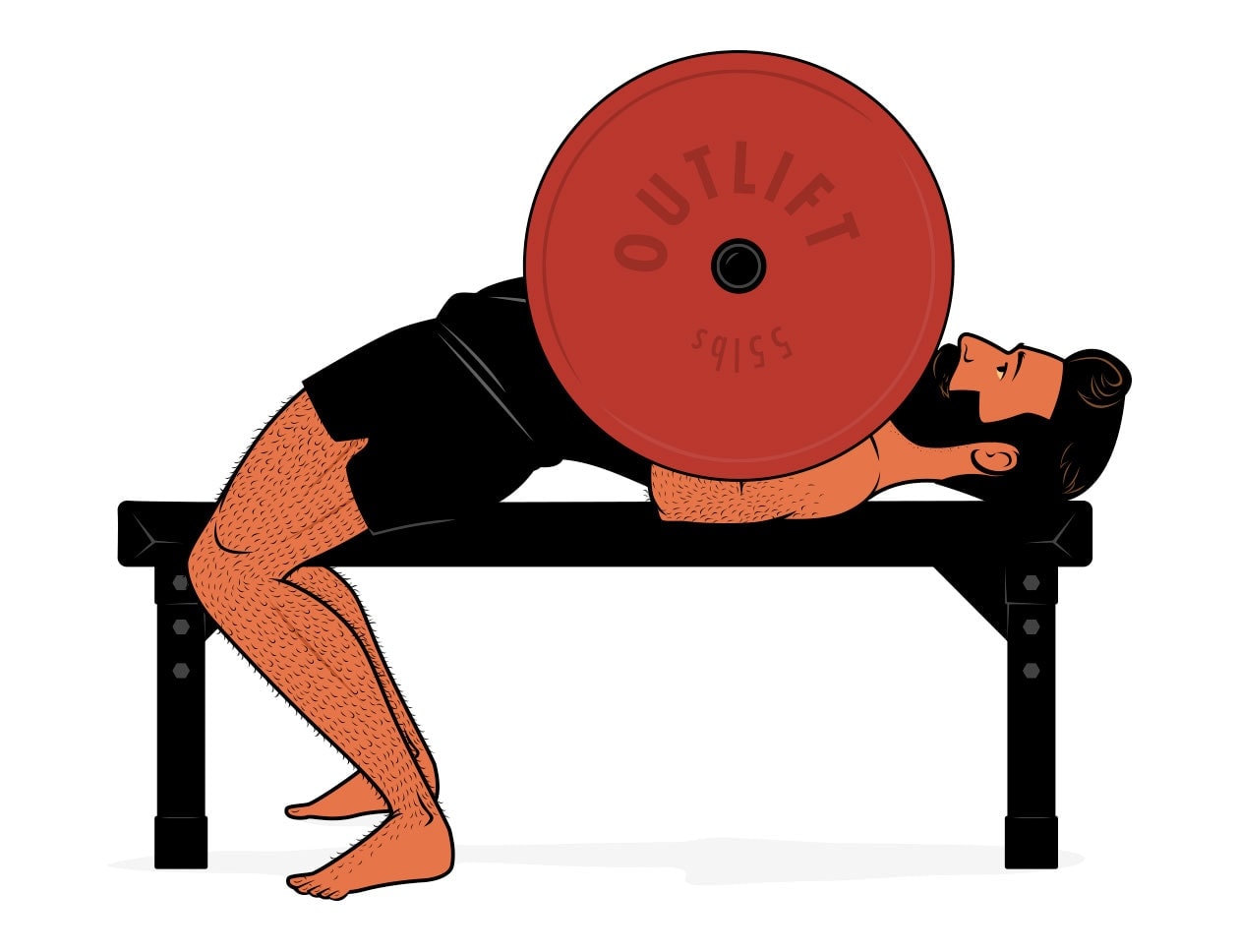

When doing the barbell row to improve deadlift strength, as is common in strength training and powerlifting programs, the barbell typically starts on the floor, shifting more emphasis to the hips and lower back:

Each of these row variations is good, but they’re both used for different purposes, and they both emphasize different muscles, as we’ll cover in a moment.

What Muscles Does the Barbell Row Work?

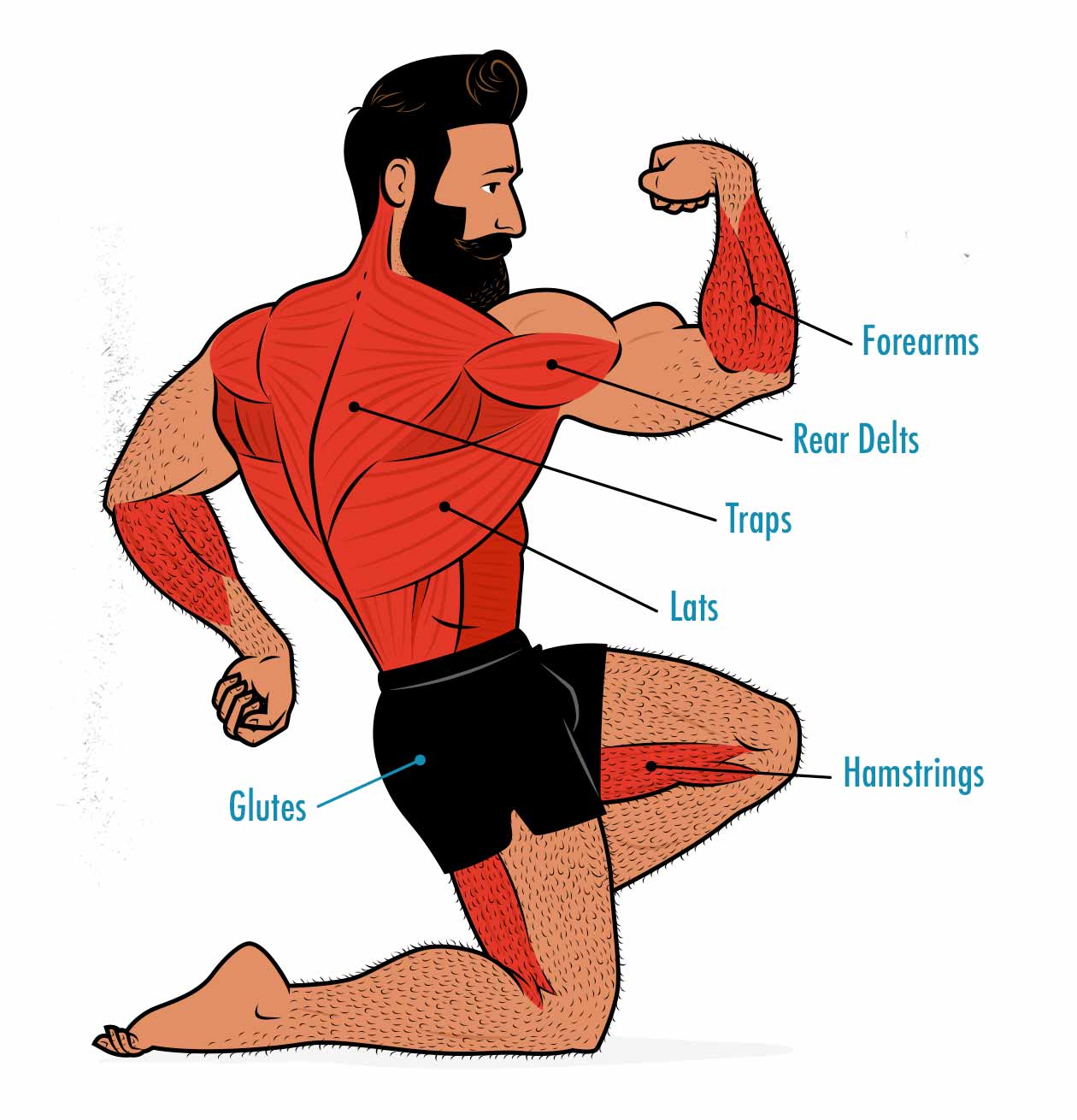

The barbell row engages a wide variety of muscles. It’s famous for being an upper back exercise, and it is, but it’s much more than that. Our muscles grow best when we challenge them in a deep stretch, and holding a hip-hinge position means holding our glutes and hamstrings in a maximally stretched position. Our spinal erectors need to help stabilize the weight, too, giving them a great growth stimulus as well. That means that while we’re rowing with our upper backs, we’re also training all of the muscles in our posterior chains:

The next thing that’s interesting about the barbell row is that it’s one of the best exercises for building bigger forearms. It doesn’t train all of the muscles in our forearms, but it does train the brachioradialis, which is fairly big and has quite a lot of growth potential:

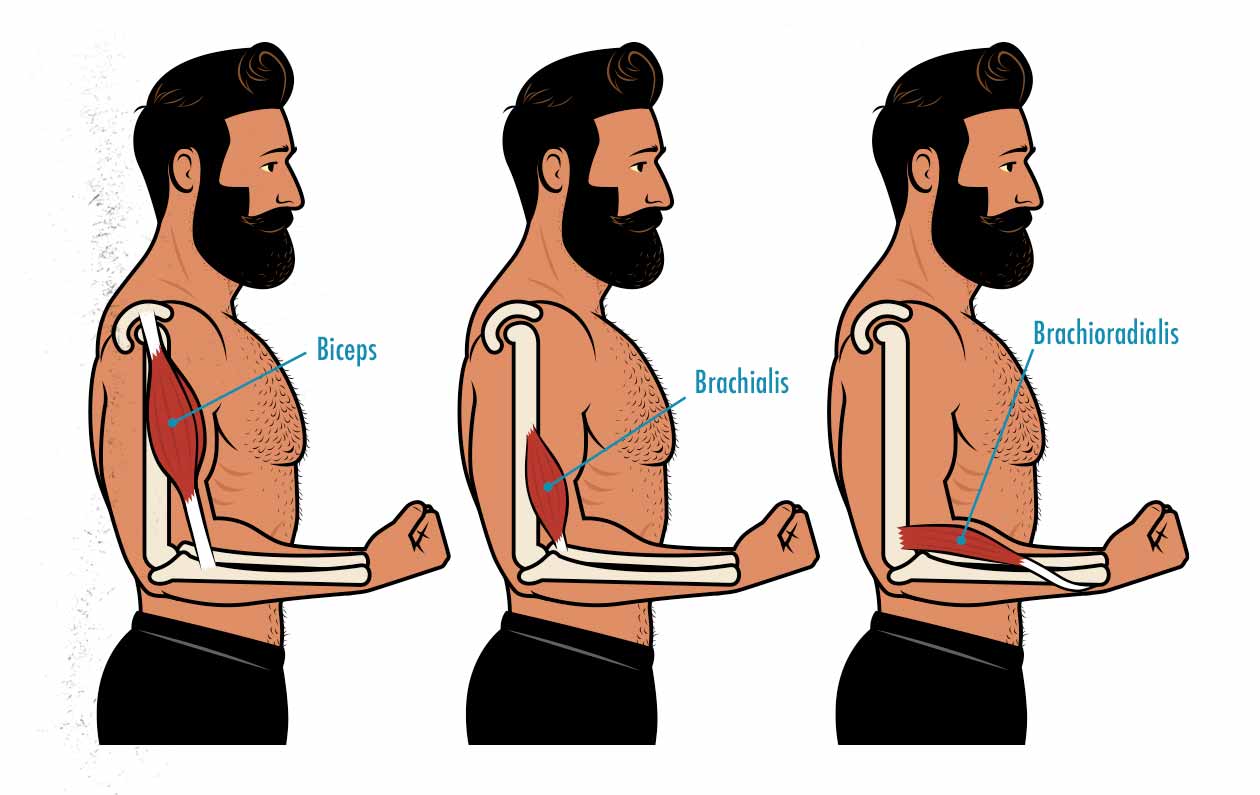

We have a few different muscles that can flex our forearms. Our biceps are the most famous, and they’re strongest when our palms are facing up. The classic barbell row doesn’t do a good job of training them unless we use an underhand grip. And even then, it isn’t one of the better biceps exercises.

The next forearm flexor is the brachialis, which sits underneath our biceps, and tends to be strongest when our palms face one another. But if you look at the brachioradialis, you’ll see that it twists around our wrists. It’s strongest when we use an overhand grip, as we do in the barbell row. That’s the muscle that helps us flex our arms when we row the barbell up. So, overall, the barbell row is a poor lift for building bigger upper arms, but it’s a great compound lift for bulking up our forearms.

How to Row for Muscle Growth

How to Do the Bent-Over Barbell Row

Here’s a tutorial video of Marco teaching the barbell row. Marco’s a certified strength coach with a degree in health sciences, and his specialty was helping college, professional, and Olympic athletes bulk up. He’s teaching how to row for muscle size, strength, and athleticism, not as a way of increasing your deadlift 1-rep max or power output, which we’ll cover down below.

Here’s how to set up for the barbell row:

- Foot position: plant your feet in a sturdy position, about hip-width apart. This is the same position that you’d use for a conventional deadlift.

- Grip width: like the bench press, you can use various grip widths for the barbell row. Most people grip the bar an inch or three wider than shoulder-width, but there’s nothing wrong with going a bit narrower or wider.

- The hip hinge position: the barbell row starts in a hip hinge, similar to a Romanian deadlift’s bottom position. To get into that position, you can either deadlift the barbell up from the floor or pick it up from a rack. Note that there’s no magic depth. Just go as low as you can go, getting a nice stretch on your hamstrings and keeping your spine in a neutral position, same as when doing a Romanian deadlift.

And here’s how to do the barbell row:

- Row the barbell up to your torso, thinking of driving your elbows back. Row to your lower chest if you’re using a wider grip; row lower in your stomach if you’re using a narrower grip. Either one is fine.

- Lower the barbell down slowly and under control, taking 1–3 seconds to lower the barbell back down. This will keep tension on your muscles, stimulating some extra muscle growth.

- Stretch your arms out. Some people row with their shoulder blades protracted throughout the lift. But as a general rule of thumb, we want to give our upper-back muscles a good stretch at the bottom of the lift. So reach out with your arms. Let your shoulder blades come apart. That extra range of motion at the bottom will help you gain more muscle size and strength.

- Row the barbell back up. No need to pause, no need to rest the barbell on the ground. Better to keep the tension on your muscles all through your set.

When it comes to depth, note that this person is rowing from a bit below the knee. If you can go deeper without needing to round your back, great. Your mobility should determine the depth of your hip hinge.

The Best Barbell Row Grip Width

Using a wider grip and rowing the bar to your lower chest will work the rear delts and traps a bit harder, whereas gripping narrower and rowing lower on the stomach tends to hit the lats a bit harder. Neither is better or worse. It just depends on which muscles you’re trying to emphasize.

A good default is to grip the bar a bit wider than your deadlift, a bit narrower than your bench press. That usually winds up being an inch or three outside the smooth of the barbell. Then, if you notice that you aren’t stimulating your lats, grip the bar a bit narrower and row lower on your torso. Or, if you’re only feeling it in your lats, try gripping a bit wider and rowing a bit higher

The Best Barbell Row Rep Range

The barbell row is a big compound lift that can be loaded quite heavy. In strength training routines, it’s common to do them for sets of 5 repetitions. The thing is, when doing rows for 5–8 reps per set, it’s common for guys to have trouble maintaining their spinal position. And even when they do, they have trouble feeling the muscle working their upper-back muscles. Instead, they feel fatigued in their hips and lower backs, not unlike when doing deadlifts.

When doing rows for 15–20 reps per set, our cores can easily support the weight, allowing us to work our upper-back muscles harder, stimulating more muscle growth. Another benefit is that our lower backs won’t get quite as fatigued, saving our energy for our other lifts, such as the squat and deadlift.

Should We Use Lifting Straps for Barbell Rows?

As a general rule of thumb, beginners often benefit from avoiding lifting straps. But as they get stronger, grip strength often becomes a limiting factor on lifts that aren’t designed to tax our grip. The barbell row is one of those lifts. We aren’t rowing just to improve our grip strength; we’re also trying to bulk up our upper backs and posterior chains. If your grip strength is limiting you, then it can make sense to get some lifting straps.

There are several different types of lifting straps and grips. Mike Israetel, PhD, is a fan of Versa Grips (affiliate link). Compared to regular lifting straps, and I agree—they’re much more convenient. We’ve also written a full article about lifting straps, going over the pros and cons.

The Best Barbell Row Variations

The Pendlay Row (Powerlifting Variation)

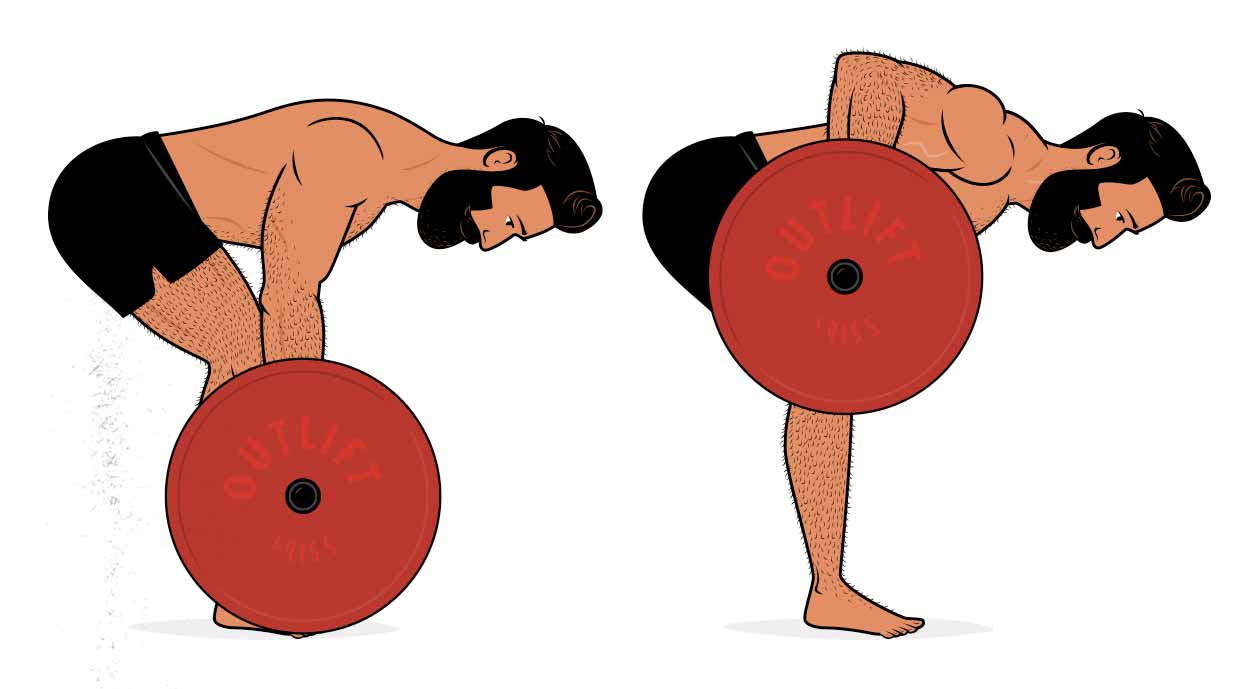

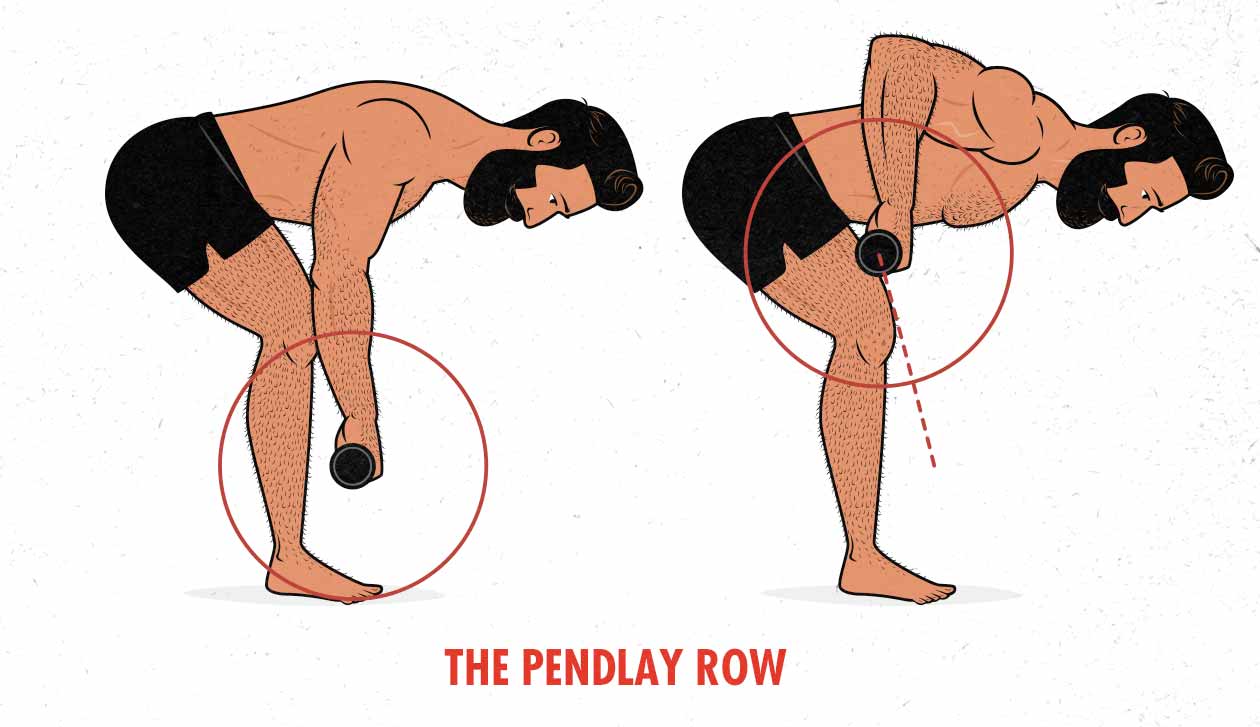

The Pendlay row is named after the famous weightlifting coach Glenn Pendlay. It’s a variation of the bent-over barbell row that’s popular with powerlifters. It’s got a similar setup to the deadlift, and like the deadlift, it emphasizes the hips and lower back. And so, if the purpose of your barbell row is to increase your deadlift strength, this is a good choice.

To do a Pendlay row, start in a conventional deadlift position and row the barbell from the floor, as shown above. Then, similar to the deadlift, let it fall quickly back down. This is how the barbell row is taught in most strength training routines, such as StrongLifts 5×5 and Starting Strength.

In bodybuilding routines, the barbell row is used to build size in the upper back and forearms. The goal isn’t to improve hip strength but rather improve our upper-body muscle size, strength, and aesthetics. To do that, people will do a bent-over barbell row. They start in a Romanian deadlift position and row the barbell from midair, like so:

The bent-over barbell row shifts the emphasis to your upper body, making it a better lift for bulking up your upper back and forearms. Each repetition is done with a bodybuilding lifting tempo, lifting explosively and lowering slowly and under control. This helps to build muscle on both the way up and the way down. Plus, since the weight is never resting on the ground, tension is kept on our muscles throughout the set, making it quite a bit better for building muscle.

Both barbell row variations are good exercises, and both are quite good for gaining general strength. After all, in either case, you need to support the weight with your hips and spinal erectors, then row it up using your upper back muscles. But if you’re trying to gain muscle mass in your upper back and forearms, it’s usually better to do a bent-over barbell row, rowing from midair and lowering the weight back down slowly.

The Yates Row (Biceps Variation)

The Yates row is a variation of the barbell row popularized by the famous bodybuilder Dorian Yates. Like the bent-over barbell row, it’s done from a hip hinge position, never letting the barbell touch the floor. What makes it unique is that you use an underhand grip to shift some of the emphasis from your forearms to your biceps.

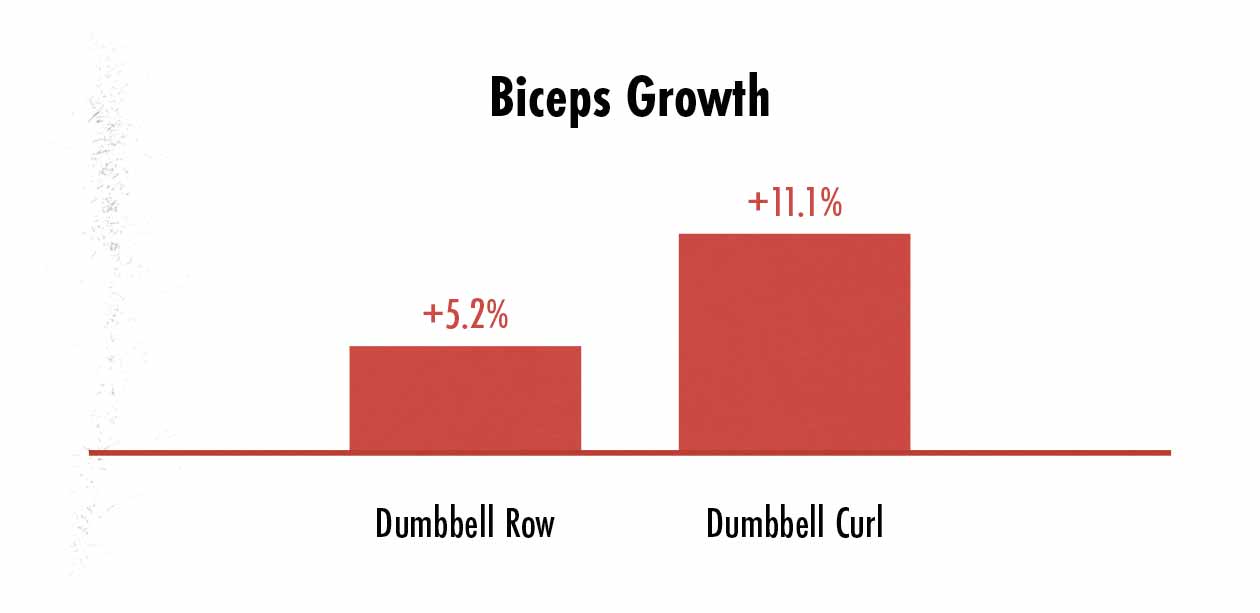

The problem with the Yates row is that the strength curve isn’t ideal for working our biceps. And since it isn’t good for our biceps, it’s unclear if there’s any advantage to using an underhand grip. For example, if we look at a study by Mannarino et al., we see that the biceps curl stimulates over twice as much biceps growth as the underhand dumbbell row:

This study used dumbbells, but we’d expect these same results when comparing the Yates barbell row against the barbell curl. So, although using an underhand grip probably stimulates a bit more biceps growth than using an overhand grip, it’s still not a very good biceps exercise.

With that said, just because the Yates row isn’t that great for our biceps, that doesn’t make it a bad exercise. You can use whatever grip you prefer, ranging from an overhand grip, to a neutral grip, to an angled grip, to an underhand grip. Our main goal is to work our upper backs and spinal erectors, not our arms, so choose whichever grips feel most comfortable. Ideally, you’d vary your grip over time. Overhand one phase, angled the next, underhand after that.

The Dumbbell Row (One-Arm Variation)

The next rowing variations we can compare are the barbell row and the dumbbell row. Both are quite good at working our upper back muscles, but when we’re rowing dumbbells, we usually plant our hands for support, taking the strain off of our lower backs.

It’s common for beginner lifters to struggle with their lower back stabilization and strength. If you’re already squatting and deadlifting, your lower back might already be fatigued. Then, when you’re training your upper back, it can become a limiting factor, preventing you from stimulating much growth in your upper-back muscles.

Even as an intermediate lifter with a strong lower back, you might already be working your spinal erectors quite hard with your deadlifts and squats. If your spinal erectors are already overworked, it can help to choose a row variation where they’re supported, allowing you to stimulate more growth in your upper back.

If your lower back feels strong, though, the barbell row tends to engage more overall muscle mass, giving you more bang for your bulk.

The T-Bar Row (Chest Supported)

Our article on exercise machines covered a new study by Schwanbeck et al., showing that muscle growth from exercise machines was comparable to muscle growth from barbell lifts. We still recommend defaulting to barbell or dumbbell lifts, but machines can work quite well if you know what you’re doing.

What makes the t-bar row machine unique is that it improves the barbell row’s strength curve. See, the barbell row is hardest at the top of the range of motion, where our lats are the weakest, and easiest at the bottom of the range of motion, where our lats are the strongest. Worse, it’s when our muscles are stretched that we can stimulate the most muscle growth. Now, that doesn’t mean that the barbell row is a bad lift. After all, it’s great for the hips and hamstrings, and it works several other muscles in our upper backs, not just our lats.

What’s nice about the t-bar row machine, though, is that it makes the lift harder at the bottom of the lift, easier at the top, lining up better with our strength curves. It’s a big enough improvement that when most people try it, they notice that it feels quite a bit better. They can feel their lats being hit harder.

T-bar row machines usually have a pad that supports your chest, meaning that it won’t bulk your spinal erectors. You can find machines or doodads that let you do it them without your chest supported, though. That’s why you’ll see guys setting up a barbell in the corner of the room and doing rows with it.

Alternatives to the Barbell Row

The Bent-Over Dumbbell Row

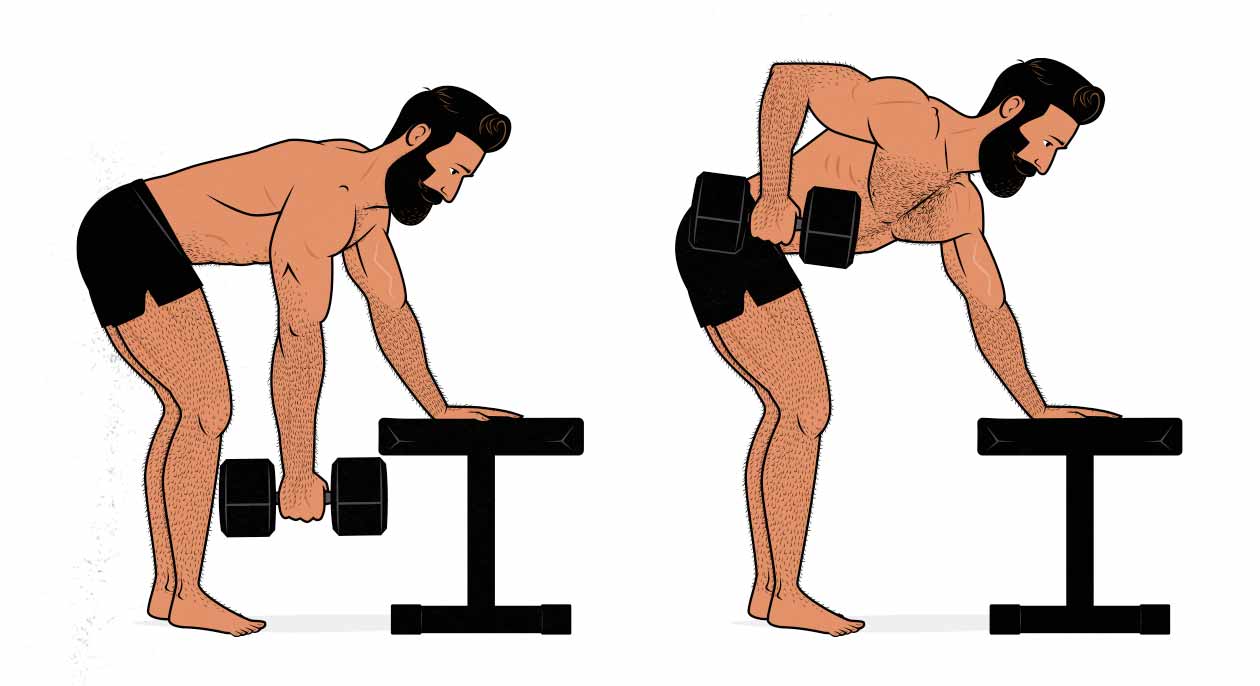

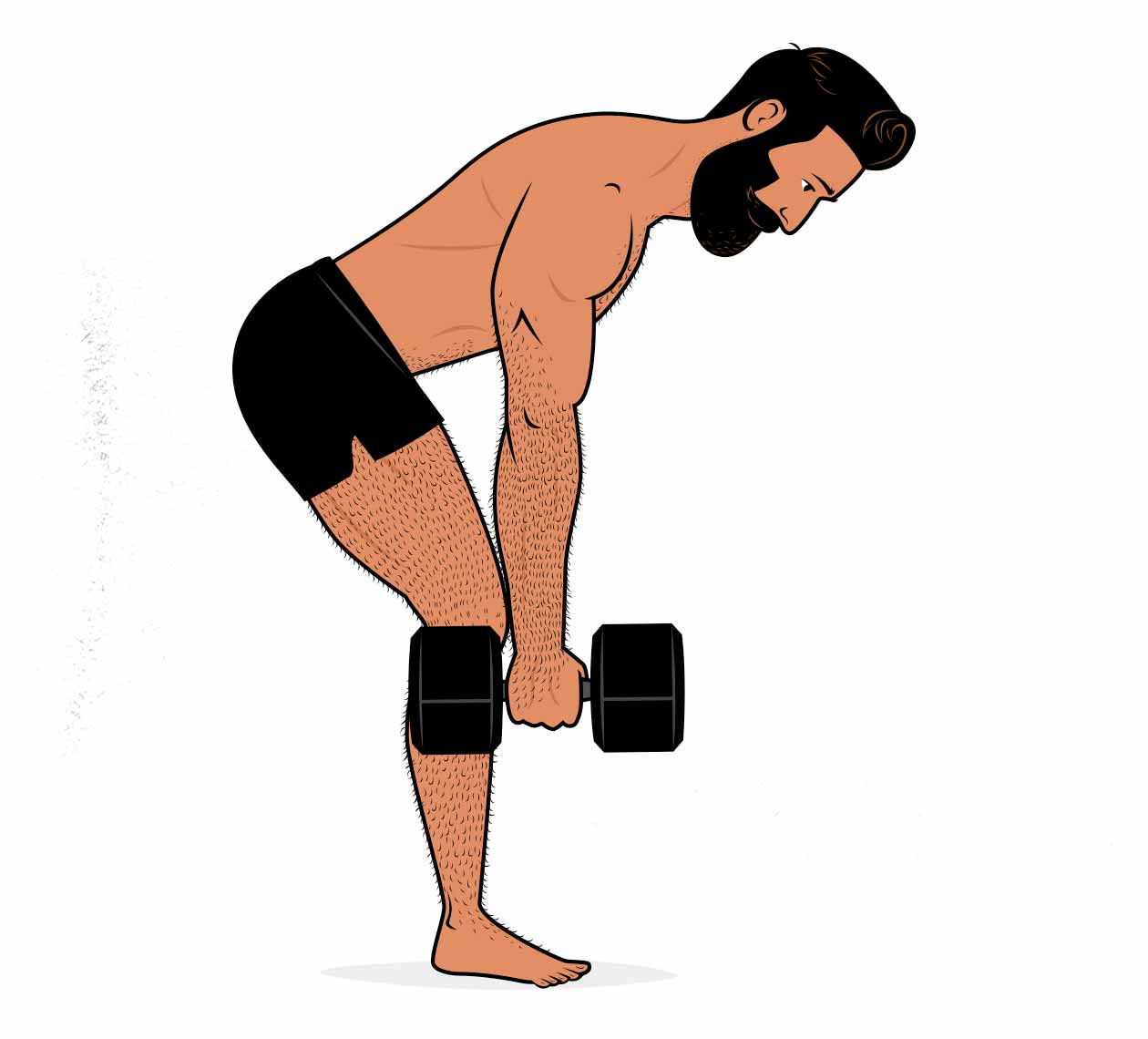

A good dumbbell alternative to the barbell row is the two-point dumbbell row, where instead of resting your hand on a bench, you row from hip hinge position, like so:

You can do these with one or two dumbbells. If you do it one dumbbell at a time, there will be less load on your spinal erectors, but your obliques will need to fire to keep your torso from twisting, making it a great core exercise. If you use two dumbbells, you’ll have twice the weight on your spinal erectors, making it more similar to the barbell row.

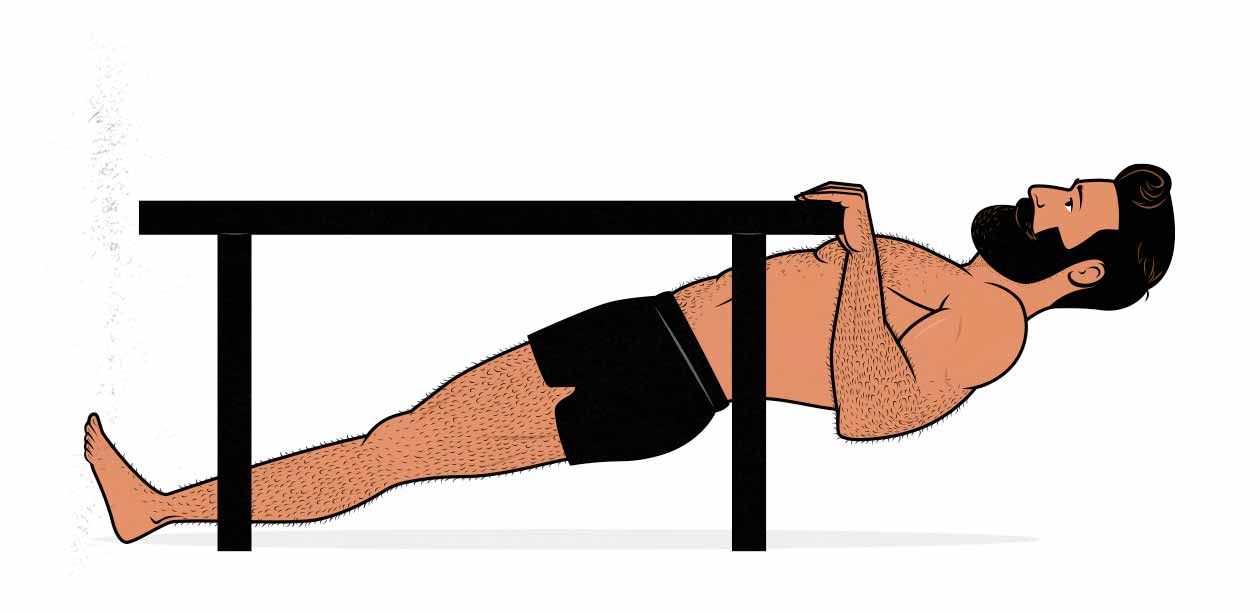

The Bodyweight Inverted Row

The best bodyweight alternative to the barbell row is the inverted row. You can do these using gymnastic rings, TRX straps, or a barbell resting on pins.

But if you’re looking for a bodyweight alternative to the barbell row, it’s probably because you’re training at home, in which case maybe your equipment is limited. In that case, no problem. If you don’t have weights, use a table.

Frequently Asked Questions

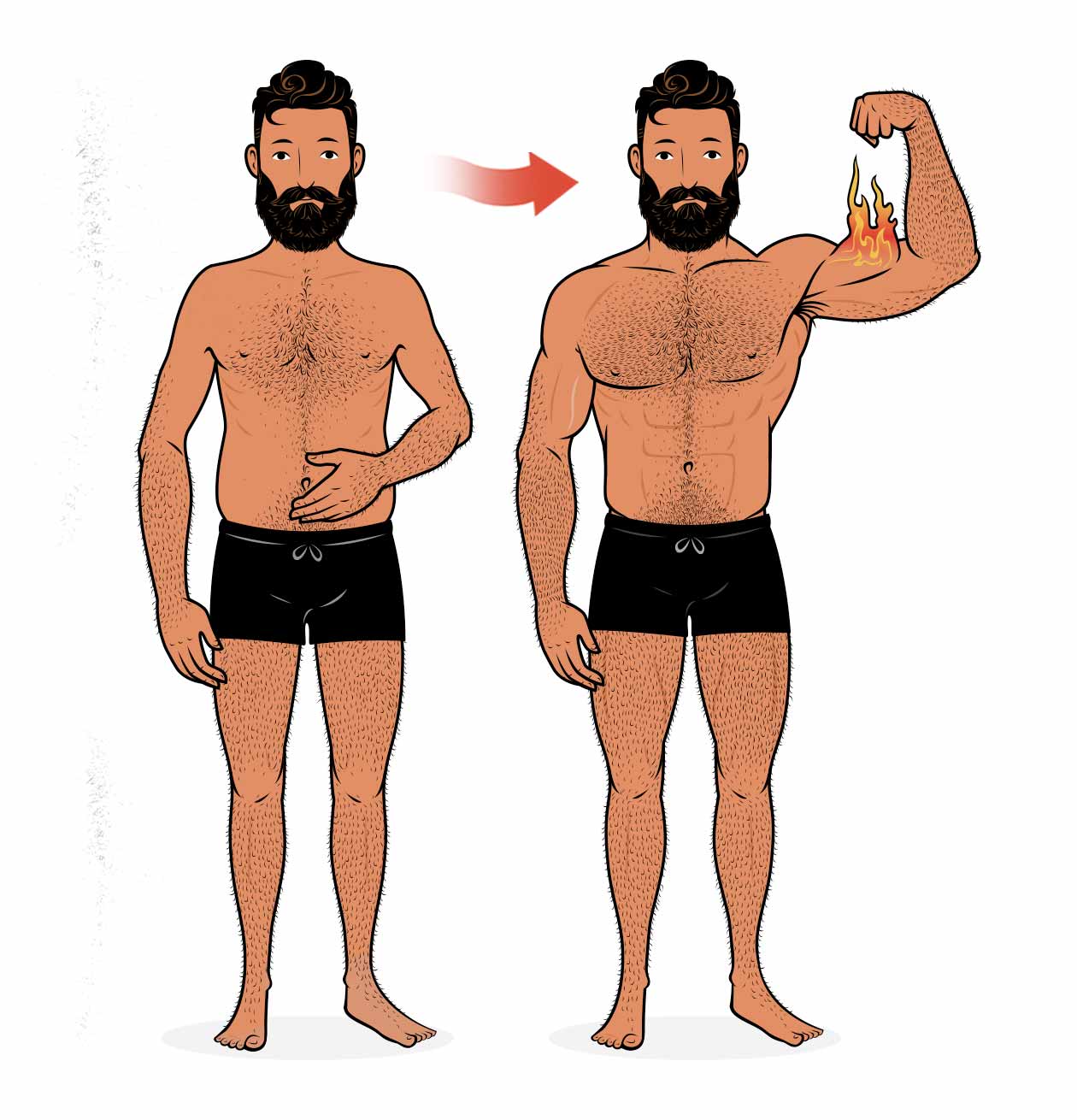

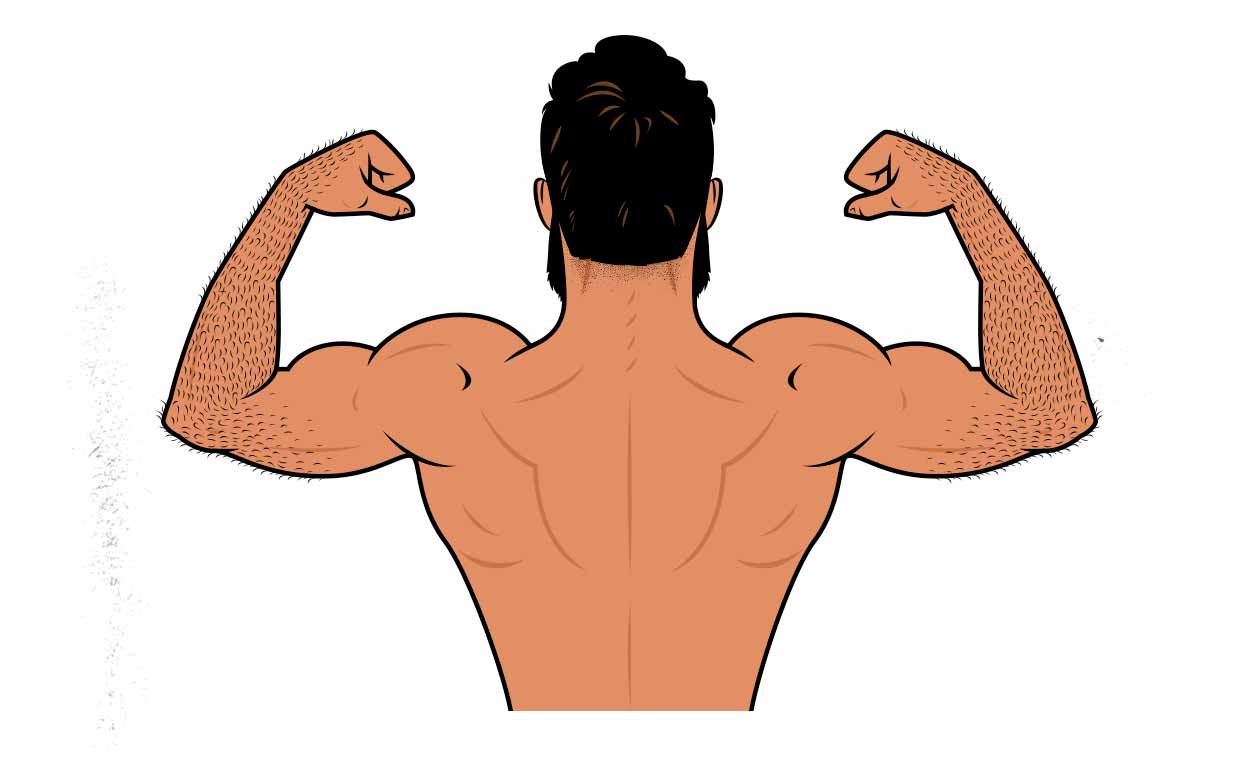

Does the Barbell Row Give You a Thicker Back?

Yes, the barbell row makes your back thicker by strengthening your spinal erectors. This makes it unique from several other back lifts, such as the chin-up, dumbbell row, lat pulldown, and pullover, which don’t train our spinal erectors.

There’s an old bodybuilding adage that vertical pulls, such as the chin-up, give us wider backs, whereas horizontal pulls, such as the barbell row, give us thicker backs. If you look at the muscles being worked, you’ll see that there’s some truth to that.

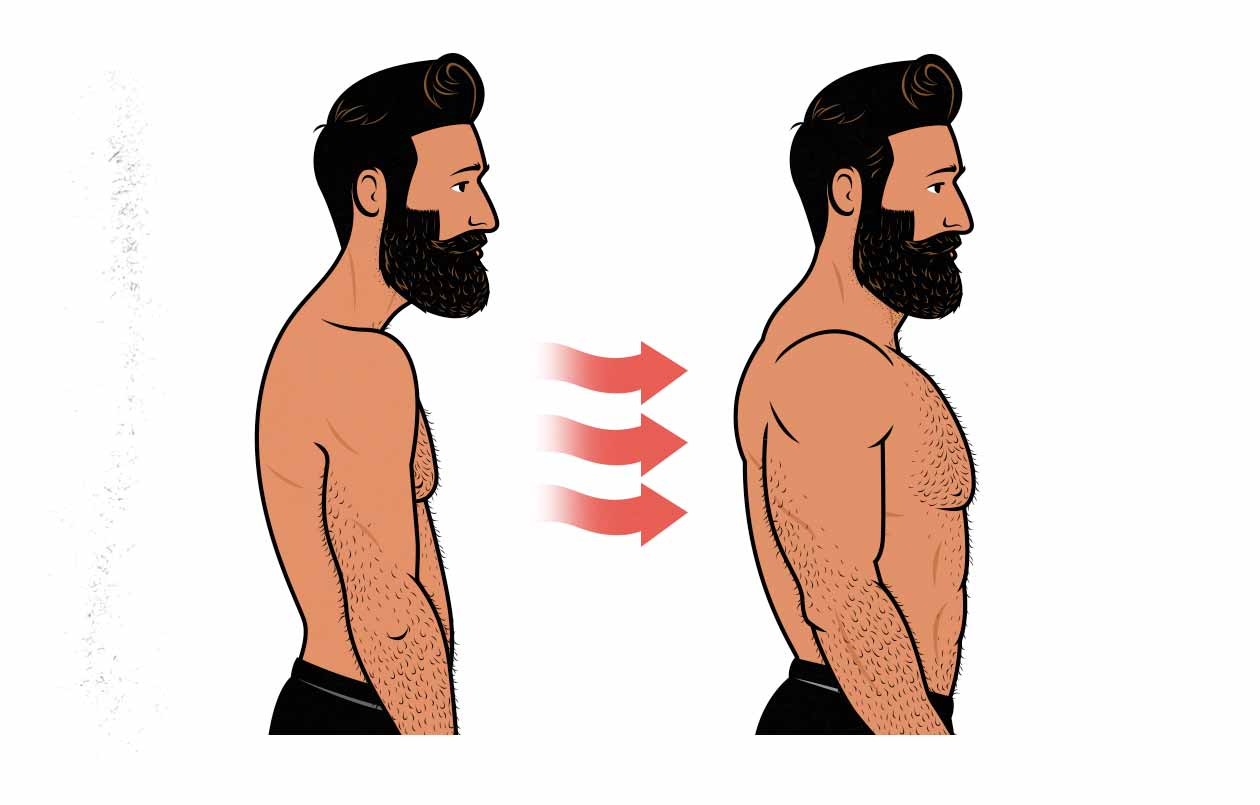

Chin-ups are great for training the lats with a large range of motion and with a deep stretch, giving us wider backs, but they don’t train our spinal erectors, meaning they won’t make our backs thicker. On the other hand, the bent-over barbell row isn’t quite as good at training our lats. The range of motion is smaller, and the resistance curve isn’t as good. But it’s quite good for training our spinal erectors, meaning that it will do a good job of making our backs thicker, like so:

The catch is that if you do your rows with your back supported, such as with one-armed dumbbells rows, seal rows, chest-supported rows, or t-bar machine rows, then you won’t be training your spinal erectors, and so you won’t be building a thicker back. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that, especially since the front squat and conventional deadlift can both do a good job of training the spinal erectors. It just helps to know the differences between different lifts.

So, yes, vertical pulls emphasize our lats, making them good for building a wider back. And horizontal pulls—including both deadlifts and barbell rows—emphasize our spinal erectors, making them good for building a thicker back.

Are Barbell Rows Necessary to Build Muscle?

Do you need to do barbell rows? No, you don’t. Many different row variations are great for building muscle, including dumbbell rows, exercise machine rows, cable rows, and bodyweight rows. And you don’t even need to do any rowing whatsoever. Many different lifts work our upper backs, spinal erectors, and forearms:

- Deadlifts are even better than barbell rows for bulking up our spinal erectors, and they do a pretty good job of training most of our other upper back muscles, too.

- Chin-ups are even better than barbell rows for bulking up most of our upper back muscles, especially our lats.

- Reverse curls and pull-ups are great for bulking up the brachioradialis muscles in our forearms.

There’s so much overlap between the various lifts that even if your goal is to maximize your muscle growth, there’s no specific lift that you absolutely must do. If you aren’t doing bent-over barbell rows, that’s okay. You can work those muscles with other lifts.

With that said, if you have a barbell and you can do barbell rows, then you probably should. You don’t need to do them, but they’re a great lift to take advantage of.

Should You Be Able to Barbell Row as Much As You Bench Press?

No, your barbell row and bench press strength don’t need to match, and there’s no strength ratio you need to strive for. In fact, many powerlifters focus their training on the squat, bench press, and deadlift. They don’t do any back training at all. No barbell rows, no chin-ups, nothing. Their upper-back muscles are disproportionately small, but it doesn’t cause any harmful muscle imbalances or increase their risk of injury.

You’ll also find plenty of bodybuilders who invest a lot of energy into the bench press, given how great it is for building a bigger chest. But they don’t spend much time deadlifting or barbell rowing, preferring chest-supported rows, dumbbell rows, t-bar rows, and cable rows. As a result, if they tested their bench press strength against their bent-over barbell row strength, they might be able to bench twice as much as they can row, and largely because their spinal erectors aren’t very strong. But aside from having a smaller lower back, their upper-body muscles might still look quite balanced.

Finally, I can bench press 315 pounds, which is quite a lot more than I can barbell row. I can’t see any imbalance in my physique, my shoulders aren’t sloping forwards, my overall posture is pretty good, my shoulders feel stable and strong, and I have no pain. Now that I’ve accomplished my bench press goal, I want to get stronger at the barbell row. But not because I’m imbalanced, just because I want to get stronger.

So there’s no reason not to train your upper back, especially if you’re interested in becoming big and strong overall. The barbell row is a valuable lift for that, and if you give it the same emphasis as your barbell bench press, you’ll probably like the results. But if you can’t barbell row as much as you bench press, that’s totally fine.

How Much Should You Be Able to Barbell Row?

As we covered above, there’s no weight you should be able to barbell row, and your rowing strength doesn’t need to be proportional to any of your other lifts. But even so, most people can barbell row as much weight as they can bench press if they train for it. So if we look at barbell strength standards, we can make some estimations of what’s realistic.

After practicing the barbell row for a few weeks, a beginner can expect to barbell row:

- 175–185 pounds as their 1-rep max.

- 160 pounds for 5 reps.

- 150 pounds for 8 reps.

- 140 pounds for 10 reps.

After their first year of lifting, an intermediate lifter can expect to row about:

- 215-235 pounds as their 1-rep max.

- 185–205 pounds for 5 reps.

- 170–185 pounds for 8 reps.

- 160–175 pounds for 10 reps.

After 5–10 years of serious training, it’s realistic for an advanced lifter to be able to barbell row:

- 290–335 pounds as their 1-rep max.

- 250–290 pounds for 5 reps.

- 230–270 pounds for 8 reps.

- 215–250 pounds for 10 reps.

But again, keep in mind that these are just estimations. It will depend on how rigorously you’re training the barbell row, how much muscle mass you’re building (which can be limited by how much weight you’re gaining), and, of course, your genetics. These are just loose estimations of what the average man can expect to lift.

Summary

The barbell row is a great compound lift for working the posterior chain, upper back, and forearms. Not only is it great for gaining muscle size and strength, but it also serves as a great accessory lift for the deadlift. The only downside is that it’s hard on the lower back, making it better for intermediate and advanced lifters who are already fairly strong at the conventional or Romanian deadlift.

When doing the barbell row, a good default is to row from a hip hinge position, similar to the bottom portion of a Romanian deadlift. From there, keep constant tension on your muscles during the set, lifting explosively and then lowering the barbell back down slowly and under control. That will stimulate the greatest amount of muscle growth per set.

Barbell rows often work best in moderate-to-high rep ranges, somewhere in the neighbourhood of 8–20 reps, with 15 reps per set being a good default. Some people with solid lower backs can benefit from going as low as 5 reps per set, though.

If you want a customizable workout program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. Or, if you’re still skinny, try our Bony to Beastly (men’s) program or Bony to Bombshell (women’s) program. If you liked this article, I think you’d love our full programs.

Hi Shane, great article. I circuit with bench press but I have only one standard barbell, so I use the ez bar for rowing instead. Using the EZ-Bar should be fine right ?

Hey Tomas, thank you! Barbell rows are awesome to superset/circuit with the bench press. I often do the same thing. And yeah, totally cool to use an EZ-bar. Makes the grip more comfortable, I find.You can use the more overhand grip for more forearm/brachialis work, the underhand grip for more biceps/ work 🙂

I have a landmine attachment I use with my barbell for landmine presses. I bought a set of rowing handles that slide over the end of the bar allowing me to do landmine rows with parallel grip. I get the t-bar row resistance curve, but there’s no chest support so I set up in the RDL position and have to maintain tension for all 15 reps. It’s the best of the barbell row and t-bar row combined! If I want overhand or underhand grip instead, there’s also a T-shaped set of landmine row handles available.

Just curious, is the Yates Row the same as what you refer to as the Bodybuilding Barbell Row?

That’s a totally perfect setup, Kevin. You know, I should probably include that in the article, because you’re right, that’s a brilliant way to set up a t-bar row at home, and while stilling getting the benefits for your posterior chain.

The Yates Row is done with an underhand grip to bring in the biceps. But even done that way, the row isn’t that great for building bigger biceps. I’d rather use the row to bulk up the upper back and forearms, the chin-up for the upper back and biceps, and then add in some curls so that the biceps can engage without interference from the movement at the shoulder. There’s nothing wrong with the Yates Row, but as a default, I find that overhand or neutral-grip rows tend to work a bit better.

Guys, what is your opinion on that “push, pull” topic? I mean is it a science-based approach or we just witnessing personal preferences disguised as serious rules?

On a couple of sites we can see advice like this: “Doing your pull-ups before doing your overhead presses, or your rows before bench presses, will create a much more stable shoulder environment for the second of the two exercises. Your rotator cuff muscles attach to your scapulae. Increasing blood flow and tightness to that region will give the shoulder joint enough support to steer clear of unwanted injuries or general instability. It also means pain-free pressing.

Even if you’re doing a straight pressing workout, prime the shoulders to bear load by stabilizing them with a couple of high-rep sets of rows of any variation, using any means of resistance—dumbbells, cables, or even bands. The goal is just to get the upper back to start feeling a mild pump and get activated.”

Also, some say it is better to put the pull day before the push day (if we train in that manner).

Is there any truth in this? Thanks in advance.

Hey Adnan, it’s true that combining pulling and pushing movements has some research to support it. In some cases, combining pushing and pulling movements together can increase our strength on both lifts. You can see that in our article on supersets, where we use the example of the barbell row + bench press.

It’s also wise to warm up before lifting, which would take care of your shoulders. We’ve got an article on warming up here. A warm-up routine often includes a bit of shoulder work. Doing warm-up sets would also warm up your shoulders.

I’m not sure if that completely answers your questions. I’m not sure of any research showing that, say, combining pushing and pulling exercises reduces the risk of shoulder injury. It might be the case, but I’m skeptical until I see evidence of it. But even so, doing a proper warm-up routine is probably still wise.

Thank you, Shane! I have read both of the articles, which you’ve mentioned. In my view it is quite needless to say it, but still- they are great.

In the one about warm-ups, I like the fact that you are not afraid to crush the myth about the one and only real warm-up—stretching. Don’t get me wrong, I like it, in fact, I stretch a lot. Years ago, while I was training Wushu, I was doing 40- 50 minutes of stretching before training and it was absolutely devastating. Your muscles are shaking and you feel so weak.

After this, I’ve read in a boxing forum that too much stretching is making you weaker. First I thought that this is some form of desperation from boxers who aren’t flexible, but when I started to stretch less, things got better. Stretching after a workout is even better. For a warm-up, some cardio like running, jumping rope, or shadowboxing is enough. After all, after the cardio, you start with WARM-UP sets. And when I say “cardio,” I don’t mean long, exhausting cardio, I mean something like 5–20 minutes, the pace depends on the length of the workout.

About the supersets, they are a great timesaver. I like them a lot, and because of this I also feel that they are pumping your cardio quite a lot. The way of supersetting that you are talking about is also called “alternate sets” in some places. Never mind, I think that they are also good for adding lean mass. I admit that I lose some weight when I do supersets (agonist-antagonist style), but definitely, the fat is disappearing noticeably.

And about the main question, starting from the harder exercise seems most logical for me. I don’t know how true that statement is, that when you row, you stretch your pecs and that makes them stronger and ready for the next set faster. The interesting thing is that in most places people prefer starting with pushing and after this the pulling, the only exception are the biceps and triceps supersets, usually the bis coming first here. Never mind, it looks like I’ve made it quite scientific here… and I am not a scientist so that is bad.

Thank you, Adnan!

I think the main theory for agonist-antagonist supersets improving our workout performance is that they tire out the antagonist muscles. So when doing the bench press, we tire out the pecs, and so they interfere less when doing rows. That kind of thing.

Probably doesn’t hurt than when combining the bench press and barbell row, you need to do warm-up sets for both movements, though. You’re right. That’d do a great job of getting the shoulders ready to lift.

Hi, I really liked this post specially because I really want to focus on Weighted pull ups and I’m scared if will it be dangerous to only do vertical pulls for a while because I want to focus all my pulling strength in. Weighted pulls and not horizontal pulling excercises like rows. Will I be able to develop a well developed back by that?? Thanks.

Hey Emmanuel,

It’s okay to focus on vertical pulling instead of horizontal pulling. Your muscles won’t fall off, you won’t get any weird imbalances. People do it all the time. It’s nice to include rows and/or deadlifts as a way of strengthening the spinal erectors and traps, but for most of your upper back, chin-ups and pull-ups are great 🙂

Shane, I have…a massively awkward workout routine right now. There is a pullup bar in my door frame, and every time I pass through it during work hour, I do 11 pullups or chinups. At the top of the movement, I then do a controlled leg lift, then lower myself down after the leg lift ends (thus prolonging the pull/chinup).

This leads me to doing 165 per day, 5x a week. 33 wide grip pullups, 33 close grip, 22 neutral grip, 33 chinups, and 44 normal pullups. Adding weight would be beneficial for intensity, but wouldn’t play nicely with my leg lift, deteriorating pullup bar, or slightly damaged door frame.

In addition to this, I do 75 diamond pushups and 54 reachout+leg lift combo pushups split between three pushup sessions…and then I do a 2:30 wall squat while brushing my teeth (why yes, I am weird!).

I definitely am seeing good results in my upper body despite this simple routine, but I feel like I could be maximizing my time more by maybe lowering my reps and adding some alternate workouts, which is what led me here (considering replacing some pullups with bent over barb rows). I am a hard gainer that is trying to gain mass, but without fat so that I stay lean/cut (super hard to do, of course). One of my worries is that if I lower reps for pullups, that I may lose more than I gain since it’s such a great movement (and that’s ignoring the added leg lift I do).

Long story short, do you have any suggestions on how to alter this “workout” to be better for gaining muscle mass without risking any loss to gains made? I have a power cage, dumbbells, a barbell, a few kettlebells, and a pullup bar. This is a long and loaded question, so feel free to ignore it. Either way, loved the article!

This one is for Marco,

I’m sure your squat, bench and deadlift are superb, and you’re strong AF. However, based on the instructional video I just saw, you don’t look like you even lift, at least by bodybuilding standards.

That said, this addresses the ongoing debate, on whether hypertrophy and absolute strength are mutually exclusive. I personally don’t believe a bigger muscle is a stronger muscle.

I’m a skinny guy who powerlifted in the 165 lb class. A lot of bodybuilders would make comments about my lack of muscle size, though I could lift way more than them.

Hi Shane,

Although I am naturally skinny and I have gone a long way. I have decent genetics for developing nearly every muscle, especially (the shoulders, biceps, hamstrings and chest) but for some reason, I lack upper back thickness, although I have wide lats and decent development. I guess it is because I have an extremely lean and defined back. It’s interesting because last year, in 2 months, my upper back significantly grew insanely while doing lots of fronts squats, but now, while I am much stronger at the movement, I haven’t made many improvements. In that region, unlike my other muscles, I could feel bones. Could you please suggest tips on how to improve this muscle imbalance/ lagging part ?

Hey Abdulallah, part of that is just genetics! A lot of naturally thin guys have thinner ribcages. When you have a thinner ribcage, your torso looks thinner from the side. You can make it thicker by bulking up your back muscles, but it will only do so much. You won’t ever look like someone who has a different body type. Having a thinner torso isn’t a bad thing, though. It’s just part of who we are.

Front squats are amazing for bulking up the spinal erectors. Conventional deadlifts, too. And then all of the smaller lifts that assist those lifts: good mornings, hyper-extensions, reverse hyper-extensions, barbell rows, and so on. The barbell row might be the exercise that bulks up more relevant muscles at once. You’d do it in a higher rep range, probably using lifting grips, doing something like 10–20 reps per set. Personally, I’m also a big fan of good mornings.

I realize I’m kind of late to the party here but have read a few of your articles and find them helpful and insightful.

On the BB row, I always have a hard time finding room for it. With heavy and consistent squat variations, Romanian deadlifts, and good mornings, I’m never quite sure how a BB row can ever give the best bang for your buck compared to seal rows or one arm rows (DB, meadows). The solution you gave was to stick to high reps but if you’re going to do sets of 15 anyways, might as well just do an inverted row which will still make sure the upper back is the limiting factor and poses no threat to lower back recovery, which is such a precious resource for squats and hinges. Besides, one study compared inverted rows and BB rows and said that upper back and lat activation was higher in the inverted one. All that said, I keep researching and coming back to articles like this to try to find a place for it just because it’s so classic. All that in mind, For what reason would anyone ever choose the BB row when those other options are available? “Well it works your erectors as well which is nice” but why not just stick to exercises that really maximize erector work instead of trying to build them with indirect stimulus of isometric contractions?

Hey Anthony, that’s a good question, and those are good points, and I actually completely agree with you.

The reason you’d choose a barbell row is because you want the extra spinal erector work. If you DON’T want the extra spinal erector work, you’d be much better off choosing another back exercise.

I don’t think you’re wrong for not wanting extra spinal erector work, either. I’m the same way. I get more than enough spinal erector work from deadlift variations. For my rows, I prefer one-arm rows and inverted rows.

Some muscles are worked quite well when you train them isometrically, especially if their primary function is postural. You CAN train your spinal erectors with lifts like Jefferson curls, and I think that’s fine, but most people can work them more than enough with deadlift and squat variations. That’s what those muscles are for. They’re there to keep your spine stable under load. When you train that function, they grow just fine. It depends on the person, though.

Wow, I didn’t know bent-over rows also train our glutes and hams. If we are picking the barbell from a rack position and not the ground, then I suppose the glutes and hams are trained isometrically during this exercise?

Yeah, that’s right. The barbell row trains your glutes and hamstrings isometrically. That’s true if you pick the barbell up off the ground, too. The main stimulus is still from the isometric hold.

You might also get a bit of movement in the hips. Some people row with some hip drive. It depends on how still you keep them.