How Resistance Curves Affect Muscle Growth

If we want to make our muscles bigger, we need to challenge them enough to provoke an adaptation. How much our muscles are challenged depends on our leverage. By adjusting our leverage over the weights, we can change which muscles are being worked, how hard they’re being worked, and how hard they’re being worked relative to one another.

For example, by changing our leverage while squatting, we could:

- Lift heavier weights and engage more muscle mass.

- Emphasize either quad growth, glute growth, back growth, or aim for equal stimulation of all three muscle groups.

- Make the lift hard at one specific part of the lift, stimulating a smaller amount of muscle growth, or hard throughout the entire lift, stimulating a larger amount of muscle growth.

By understanding and min-maxing our leverage, we can improve how much muscle we build and how much strength we gain while lifting weights.

What’s kind of neat is that the word leverage has two separate meanings:

- Leverage: the exertion of force by means of a lever or an object used in the manner of a lever.

- Leverage: use (something) to maximum advantage.

Let’s talk about the first so that we can do the second.

Disclaimer: I took a little university-level physics, but that was over ten years ago now. This is me trying to explain and visualize what I’m still in the midst of learning. I’ll be updating this article over time as I learn more. I’m also going to err on the side of using layman terms so that the article can be read more casually.

External Moments

What Are External Moments?

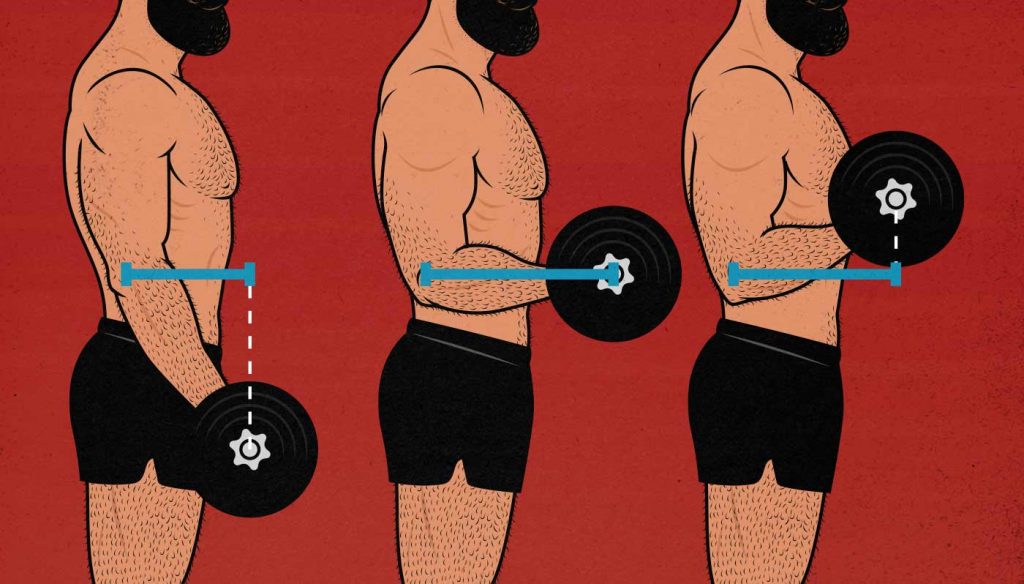

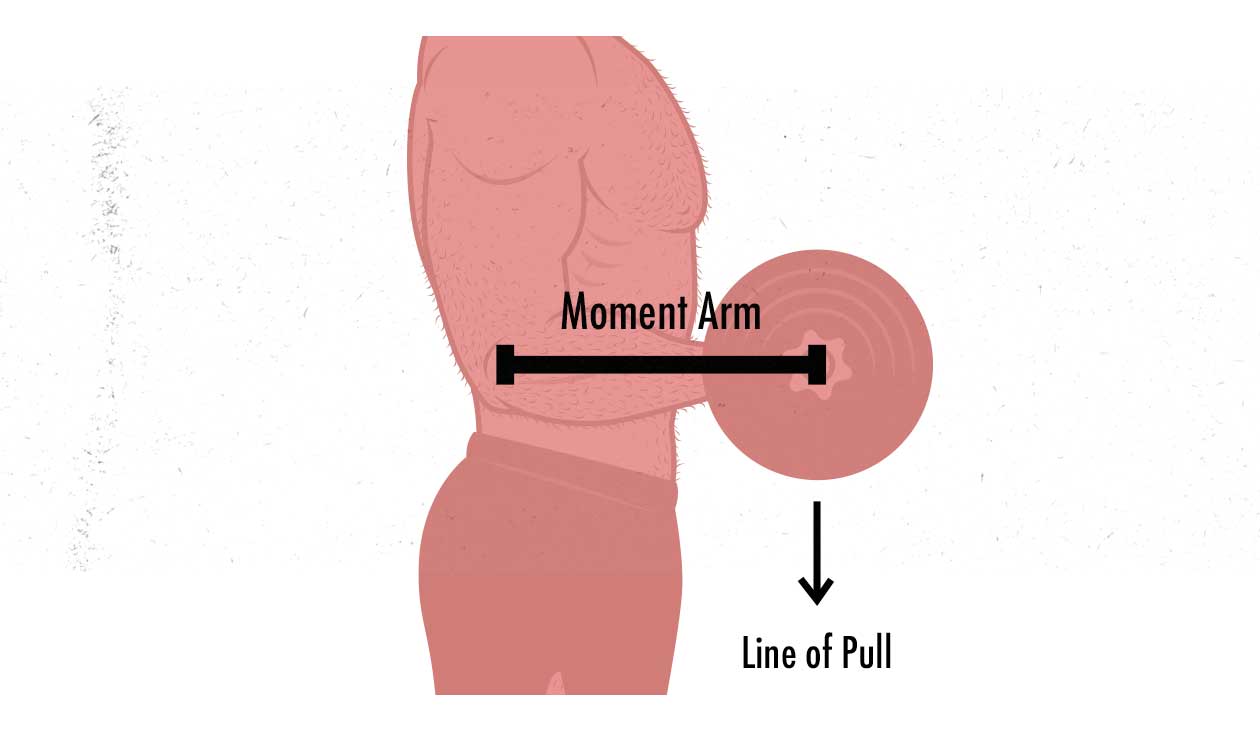

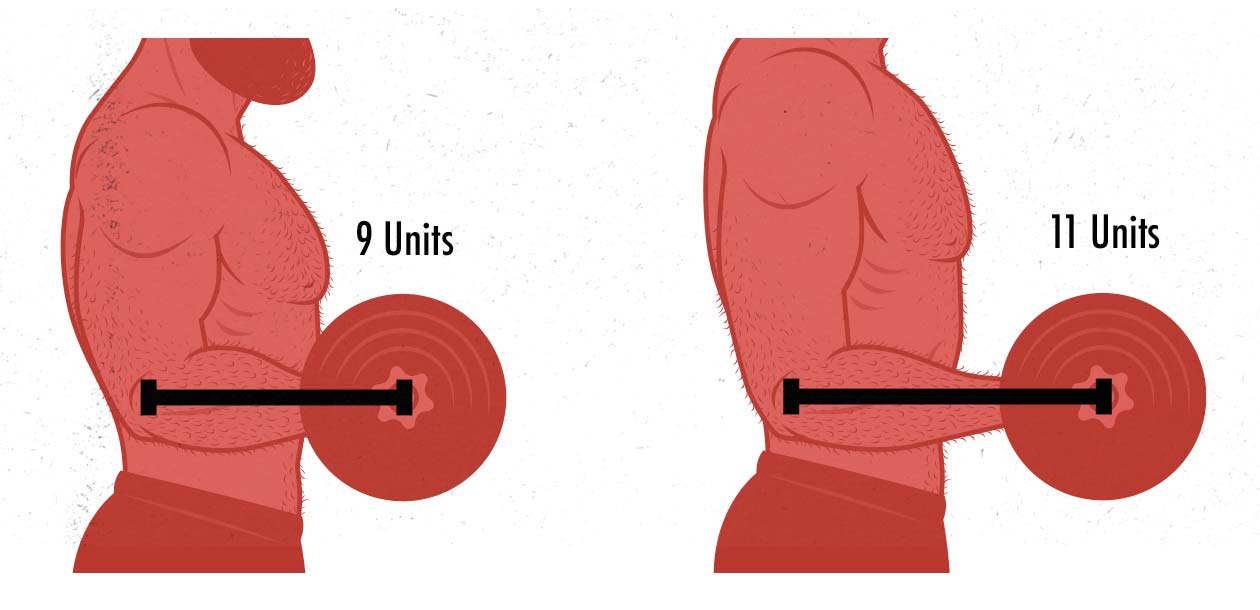

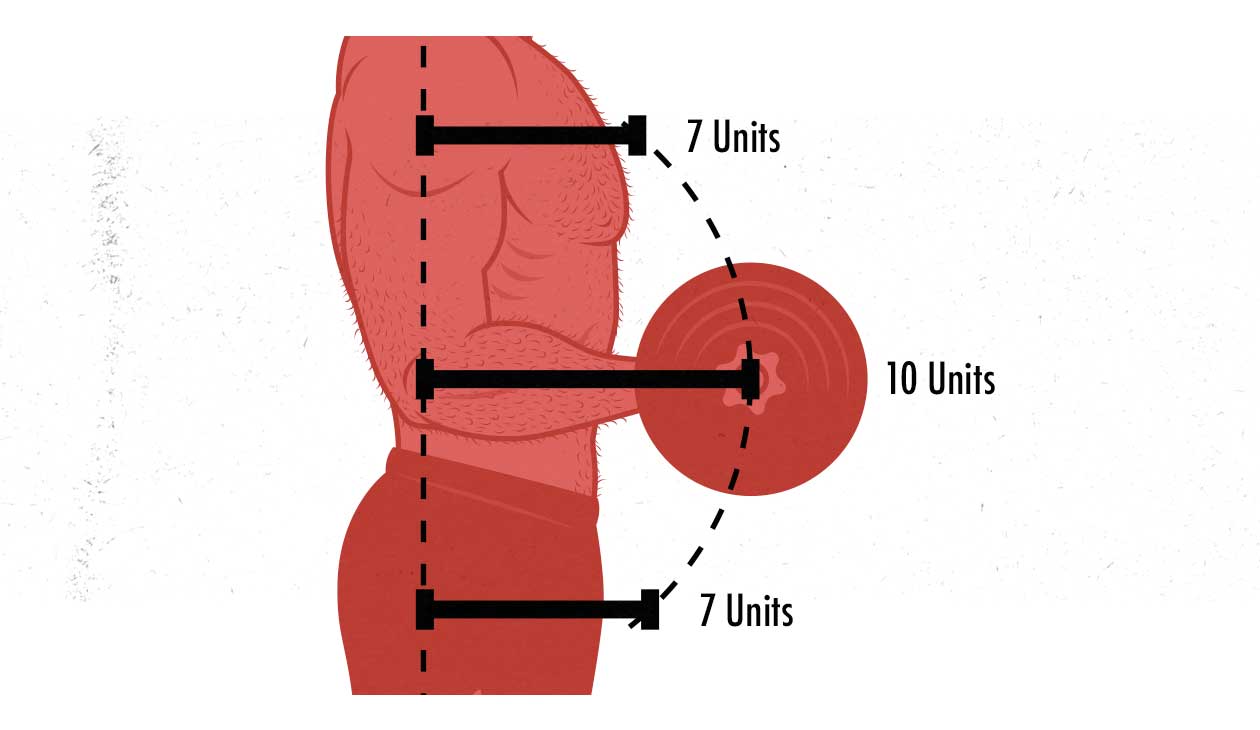

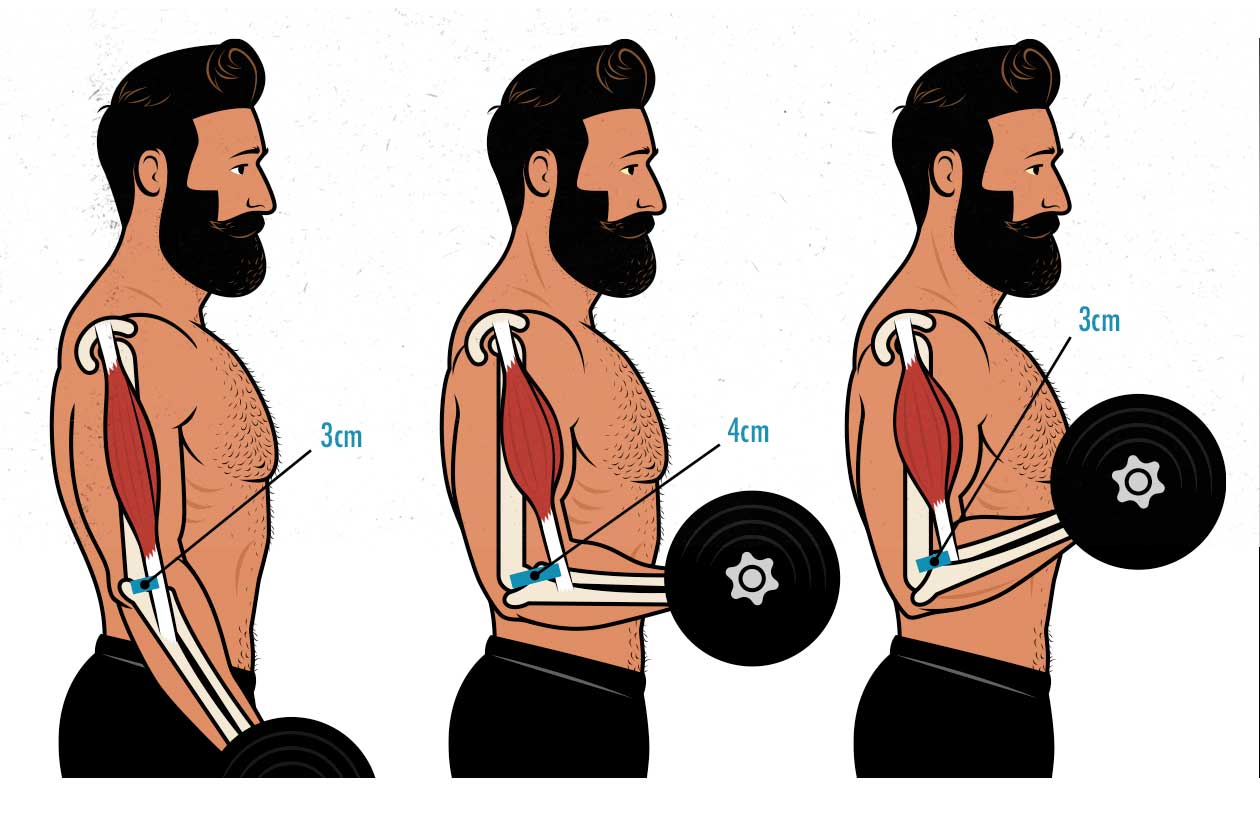

When we’re lifting free weights, gravity is always pulling the weight straight down, and so moment arms are pretty simple. The external moment arm is the horizontal distance from our joints to the weight. So in a barbell curl, the moment arm is how far in front of our elbow joints the barbell is, like so:

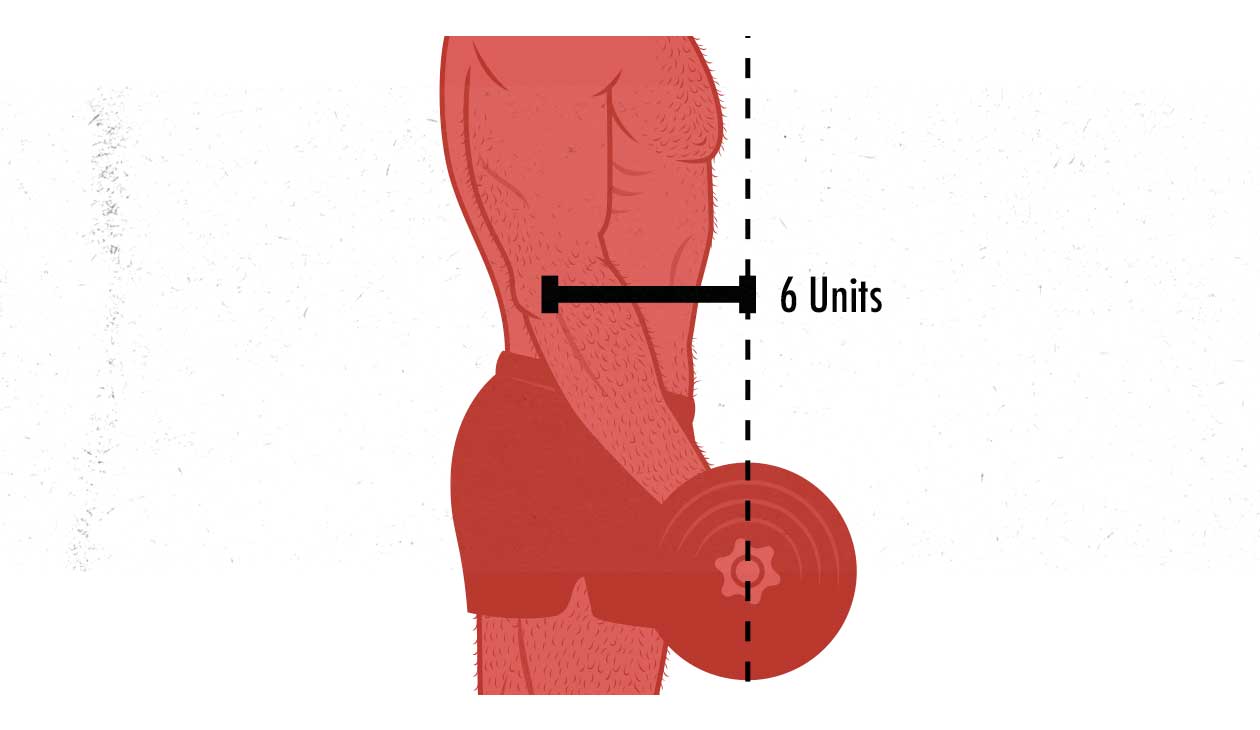

At the beginning of a curl, the barbell is close (horizontally) to our elbows, and so the weight feels lighter:

As we curl the barbell up, the moment arm gets longer, and the weight starts to feel heavier. If you lift a weight that’s much too heavy, you’ll notice that you’ll be able to get it partway up until, eventually, the moment arms overcome you. This is why we’re often able to lift more weight when doing partials—because we’re avoiding the longer moment arms.

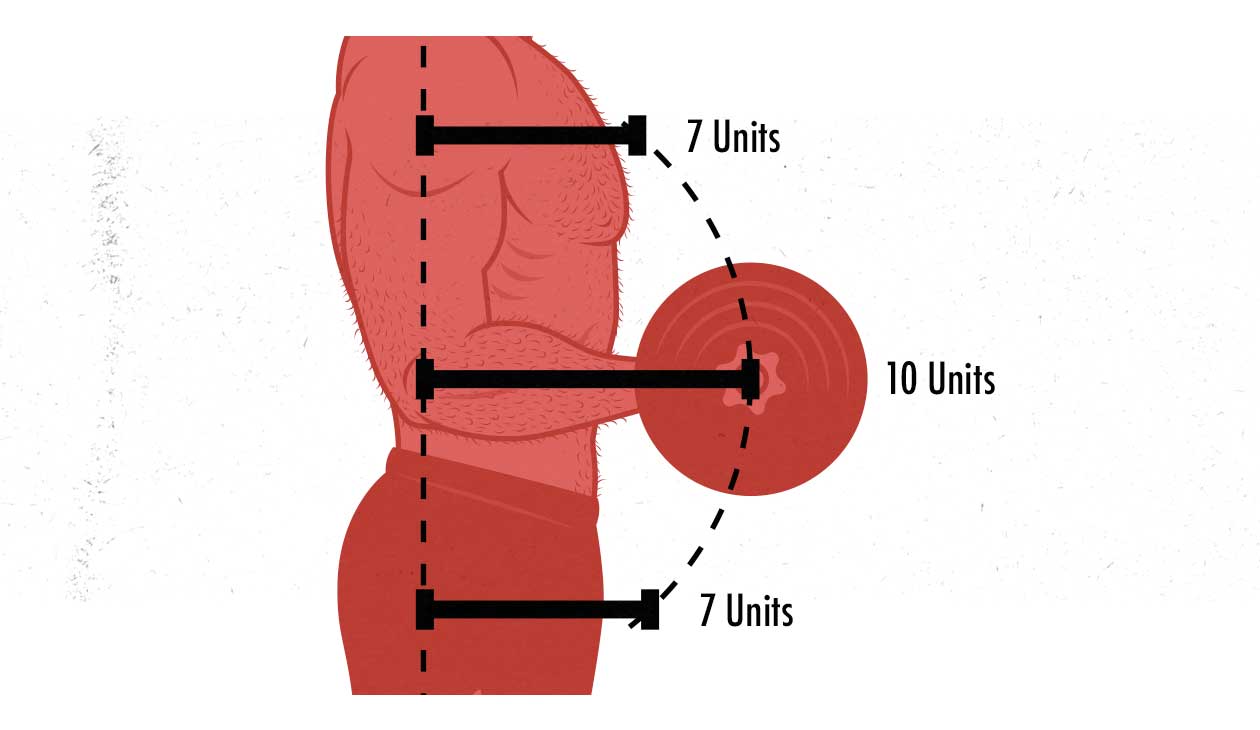

When our forearms are horizontal, the moment arm is the entire length of our forearms, which is why that’s the hardest part of the lift—where our muscles are most likely to fail us. We call this our sticking point:

If we’re strong enough to lift the weight, we’ll be able to get it up to that sticking point. If we can do that, things start to get easier again. The moment arm starts to shrink back down.

Fortunately, the math is pretty simple. In the barbell curl, the moment arm is around 40% longer at the sticking point, so the weight will exert 40% more force on our muscles, and so our muscles will need to work 40% harder (ignoring the internal moments, which we’ll get to in a moment).

External Moments & Height

Now, obviously, the length of our forearms can vary quite a lot, changing the length of the moment arms, and meaning that a tall person often needs to work quite a bit harder to curl the same amount of weight:

In this case, the taller guy’s dumbbell is exerting 22% more force, meaning that his muscles need to work that much harder to lift the weight. forgetting all other factors, if these guys have equally strong biceps, then the short guy might be curling 50 pounds, the taller guy curling 40 pounds.

However, if our goal is to get bigger, stronger, healthier, and better looking, then we aren’t interested in how tall we are, we’re just interested in making our muscles bigger. And besides, taller people can often gain more muscle mass, internal moment arms can vary with height, and so on. So let’s save these anthropometric differences for another article and go back to talking about the sticking point of the lift, which absolutely factors into getting bigger and stronger. And fortunately, the sticking points don’t really change. Regardless of how tall we are, the moment arms in the curl will always be longest when our forearms are horizontal.

Min-Maxing for Size Versus Strength

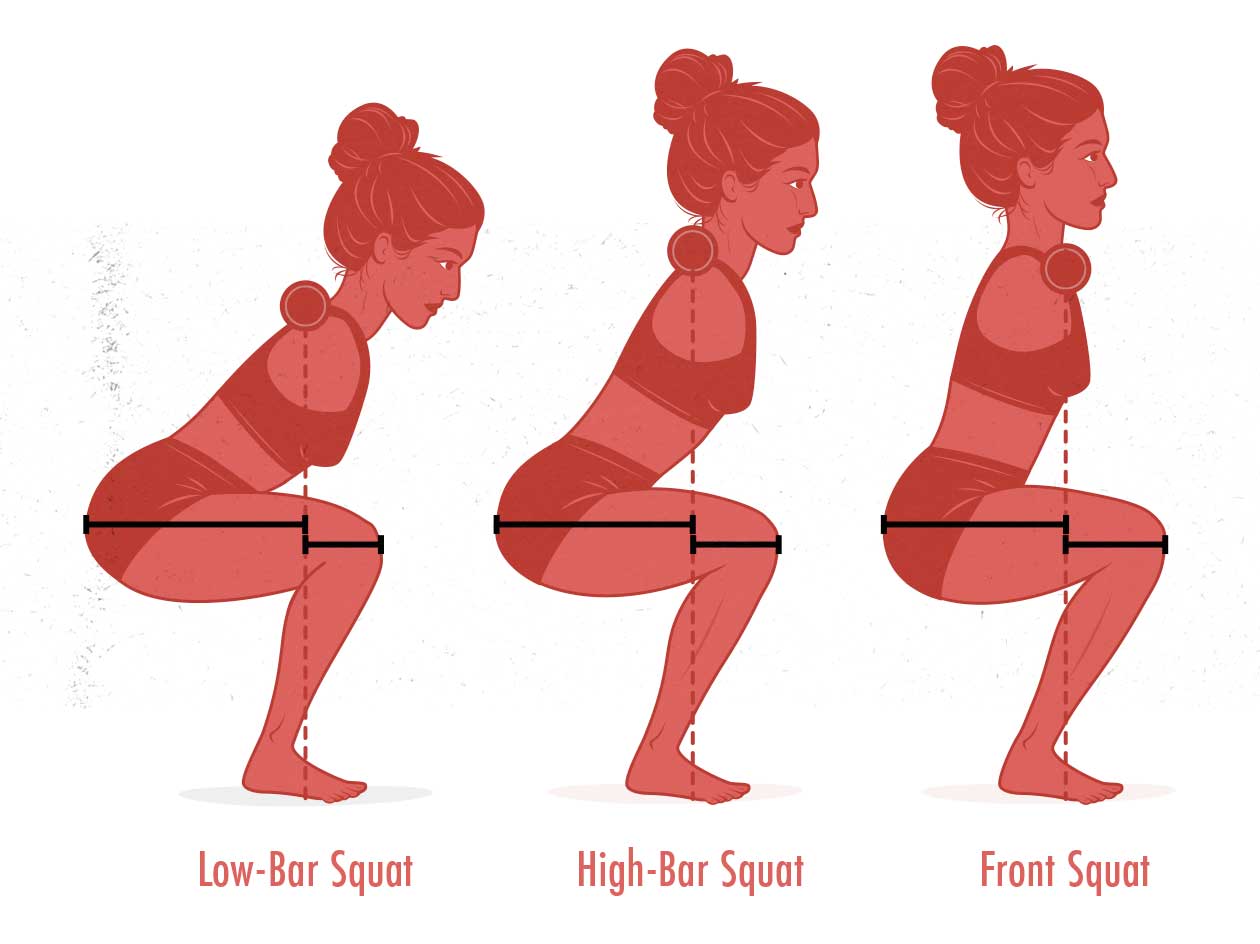

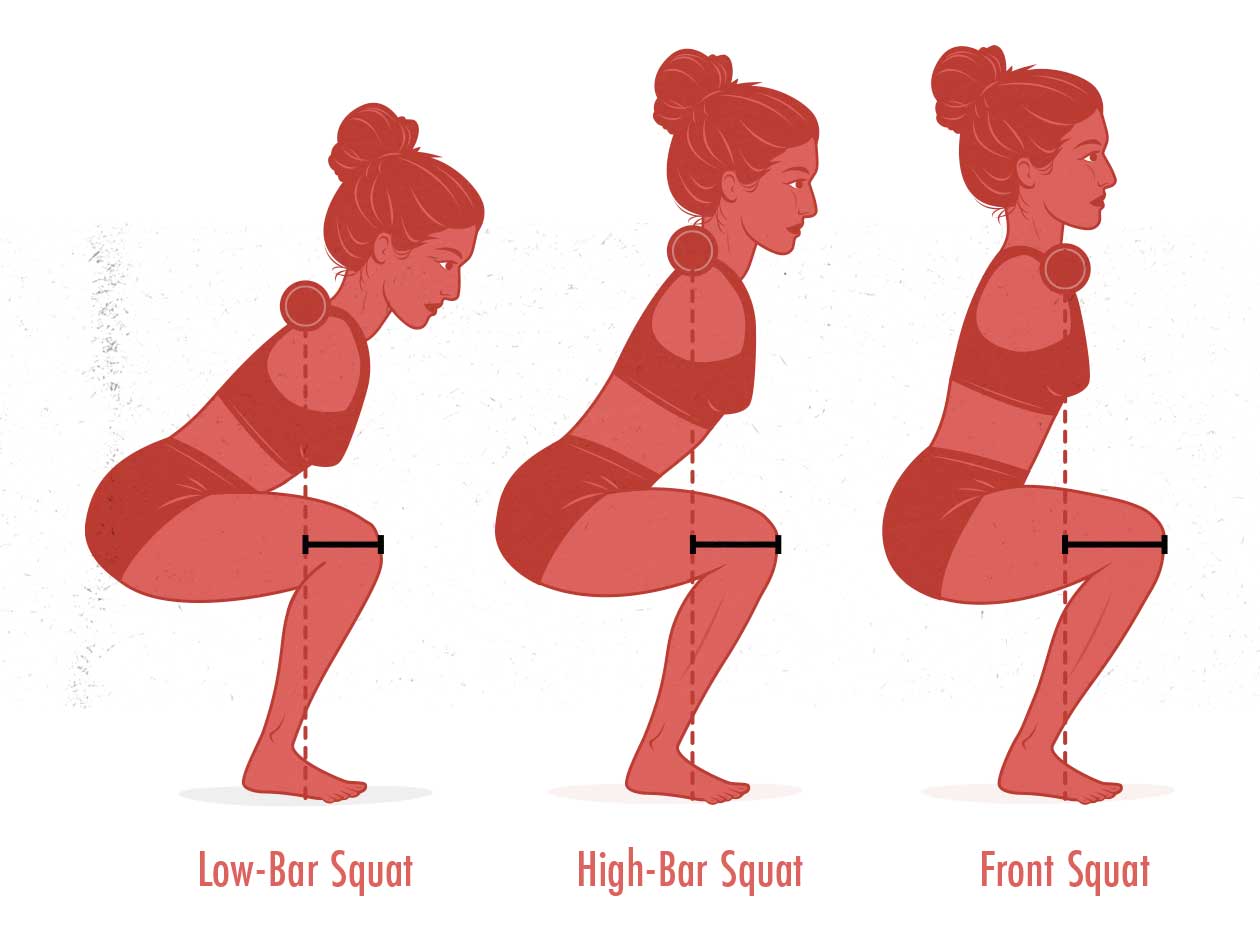

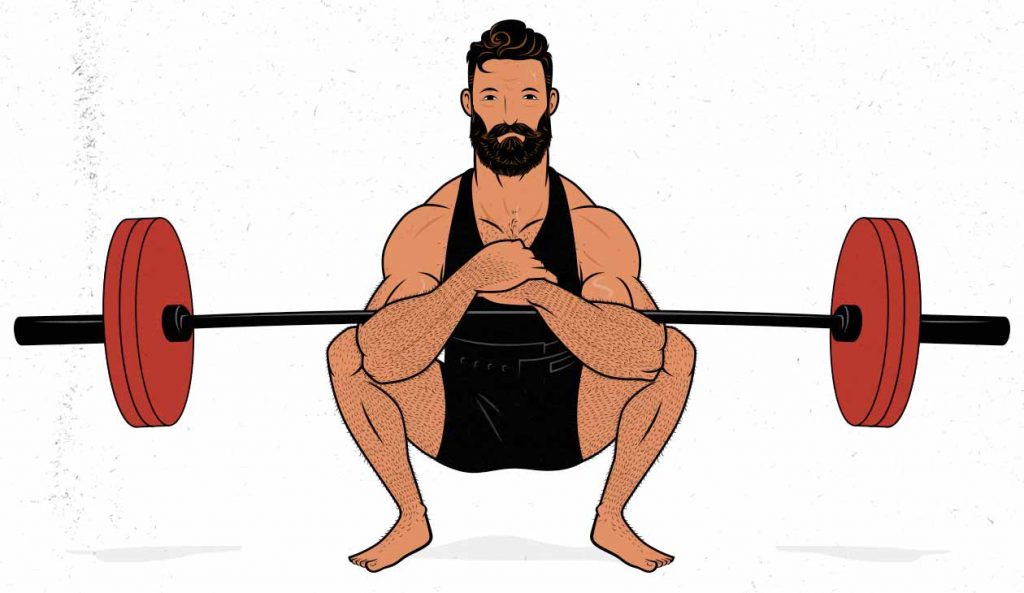

The sticking point is fairly consistent for most lifts. For example, with the squat, regardless of how long our legs are (or even which squat variation we do), the moment arms for our knees and hips are the longest when our thighs are perpendicular to the floor:

The sticking point is important because that’s where our muscles work the hardest. For building muscle, this matters because the regions of our muscles that are being stressed at this sticking point will grow the most. For gaining strength, this matters because it’s our sticking point that determines if we’re strong enough to lift the weight. So for both size and strength, the most important part of the range of motion is the sticking point.

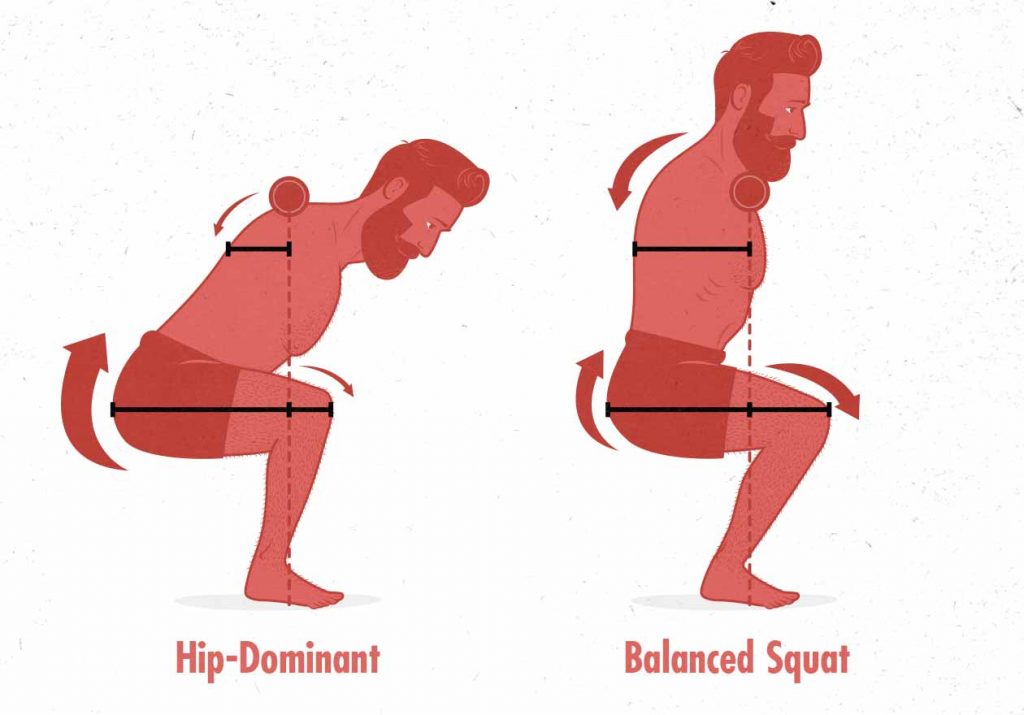

If we were merely trying to lift more weight, we’d want to minimize these moment arms, and that’s a big part of powerlifting—setting up and executing the lift with maximal leverage. The better our leverages are at the sticking point of our squats and deadlifts, the more weight we’ll be able to lift.

For example, with the squat, most people fail due to their quad strength. Since our quad strength is what limits performance, those are the moment arms that will determine how much weight we can lift. Above, we see that the moment arms for our quads are the shortest on the low-bar squat, making the lift easier on our quads, and thus allowing us to lift more weight. This makes the low-bar squat a great squat variation for powerlifting.

For building muscle, though, it’s a little more complicated. We aren’t just trying to lift more weight, but also to challenge our muscles enough to provoke growth. After all, the smaller the moment arms are, the easier it is for our muscles to lift the weight, and that’s not always what we want. Sometimes lengthening moment arms is an opportunity to stimulate more muscle growth.

When it comes to our quads, because the front squat has longer moment arms for our quads, they’re able to stimulate equal amounts of muscle growth even though we’re using less weight. So for our quads, both squat variations are equally effective. But if we compare the other moment arms, we notice something interesting.

When we move the barbell from behind our backs to in front of our bodies, Greg Nuckols, MA, calculated that we’re moving the barbell 235% further away from our upper-back muscles, more than doubling how much force they need to produce:

Is that good or bad? It depends! If we were already being limited by our upper-back strength, then lengthening the external moment would just force us to strip weight off the bar. If we were back squatting 315, we’d be forced to front squat 135. The lift would still be equally hard on our backs, so no loss there, but we’d lose out in every other way. All of our other muscles—our quads and glutes, especially—would no longer get a good growth stimulus.

However, as we’ve noted above, hardly anyone fails a back squat because of their back strength. We almost always fail our back squats because our quads (or perhaps glutes) aren’t strong enough. In fact, assuming our bulking program includes back-focused lifts like the deadlift, then back squats probably won’t be challenging enough on our back muscles to stimulate any back growth at all.

When it comes to the front squat, though, our backs need to do much more work, and it becomes a toss-up. Sometimes we fail because of our glutes, sometimes because of our quads, sometimes because of our backs. By lengthening the moment arm for our upper backs, we’ve made the lift similarly challenging for all three muscle groups:

What we’re seeing is that with front squats, we’re still stimulating just as much growth in our glutes and quads (study), but now we get a ton of extra upper-back growth. We’re engaging more overall muscle mass. This makes the front squat the worst squat variation for powerlifting but (arguably) the best squat variation for building muscle.

Understanding how moment arms affect the dynamics of our lifts can help us choose between front squats and back squats, sumo and conventional deadlift stances, and how wide to grip the barbell when bench pressing, whether to do pull-ups or chin-ups for our biceps, and how to pick between the overhead press and push press. It also explains why lateral raises can stimulate a ton of shoulder growth even with relatively light weights.

If we choose lifts with shorter moment arms, we’ll be able to lift more weight. If we choose lifts with longer moment arms, we’ll be able to get more muscle growth while lifting less weight. Both approaches can be valuable:

- When doing a conventional deadlift, we do everything possible to minimize our moment arms so that we can lift more weight. We start with the barbell right up against our shins and we keep our hips as close to the bar as possible. This allows us to lift the most weight possible, creating a lift that engages a ton of overall muscle mass. This is usually ideal for our main compound lifts.

- When doing a Romanian deadlift, we intentionally drive our hips as far back as possible to lengthen the moment arm for our hips, making the lift harder on our glutes and hamstrings. This creates a lighter deadlift variation that’s just as good at bulking up our hips, but far less fatiguing overall. This can be great for our accessory lifts.

External Moments & Strength Curve

The other thing to consider when building muscle is that although the sticking point is the most important part of a lift, it’s not the only important part of a lift. In powerlifting, it’s the sticking point that will make or break your lift, but with bodybuilding, we build muscle through the entire range of motion of a lift, and so our moment arms factor into every part of the lift.

That’s why the strength curve of a lift is so important for building muscle, and we’ve written a full article on strength curves.

Exercise Machines & Cables

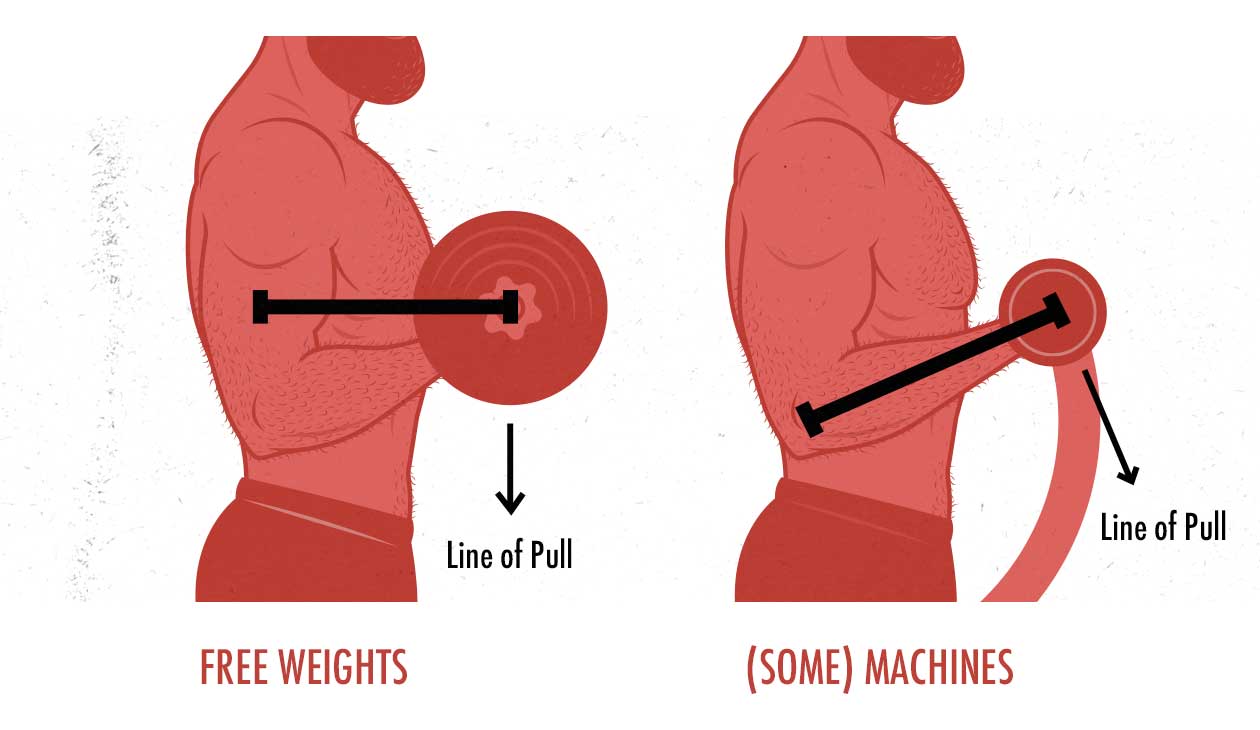

When we’re lifting barbells, dumbbells, and kettlebells, gravity will always pull the weight straight down, and so the external moments are always horizontal. When we’re using exercise machines and cables, though, the external moments will be perpendicular to the direction that the weights are pulling.

With a barbell or dumbbell curl, the weights always pull down, and so the moment arms are always horizontal. This creates varying external moments over the range of motion, like so:

But if we’re using a curl machine that pivots around an axle, then the external moments remain the same length throughout the entire lift:

This is one reason why exercise machines often feel so different from free weights: the strength curve is entirely different. And since exercise machines are often designed for a specific lift, and strength curve is considered in that design, they often have a flatter strength curve.

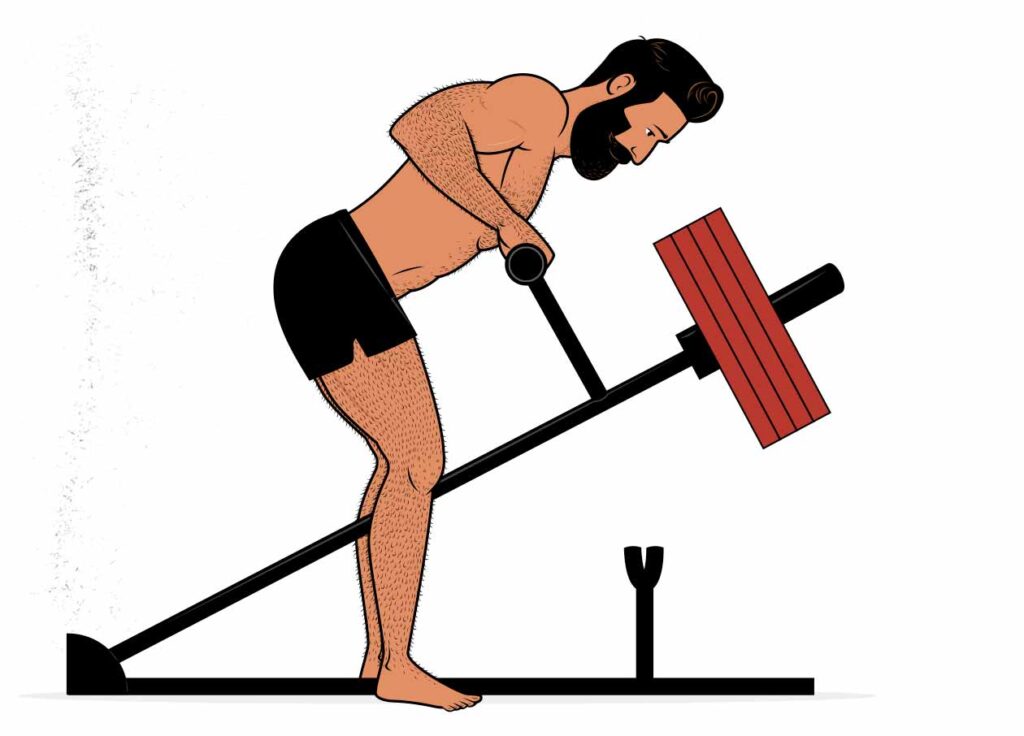

For example, let’s consider the t-bar row machine. It’s a very similar movement to the barbell row, except that as we pull the weight higher, more of the weight rests on the fulcrum. This means that the weight is heavier at the bottom of the lift, where our lats our stronger, and lighter at the top of the lift, where our lats are weaker. This gives the t-bar row a (slightly) better strength curve for building muscle.

Now, that doesn’t mean that exercise machines are always better than free weights. In fact, oftentimes free weights are better than machines. It all depends on which exercises we’re talking about. Sometimes machines are better, sometimes free weights are better, and most of the time, it doesn’t matter very much.

Exercise machines are often designed to have a flatter strength curve, which may help them stimulate more muscle growth, at least in some cases. As a result, there are some exercise machines that are better for bodybuilding than some free weight lifts.

Internal Moments

What Are Internal Moments?

Okay, so with external moments, we’ve been talking about the weights pulling down on our muscles, and how that can vary between lifts and over the course of the range of motion. Now let’s talk about our muscles pulling up on those weights, and how our strength can vary over the range of motion. This is where our internal moments come into play.

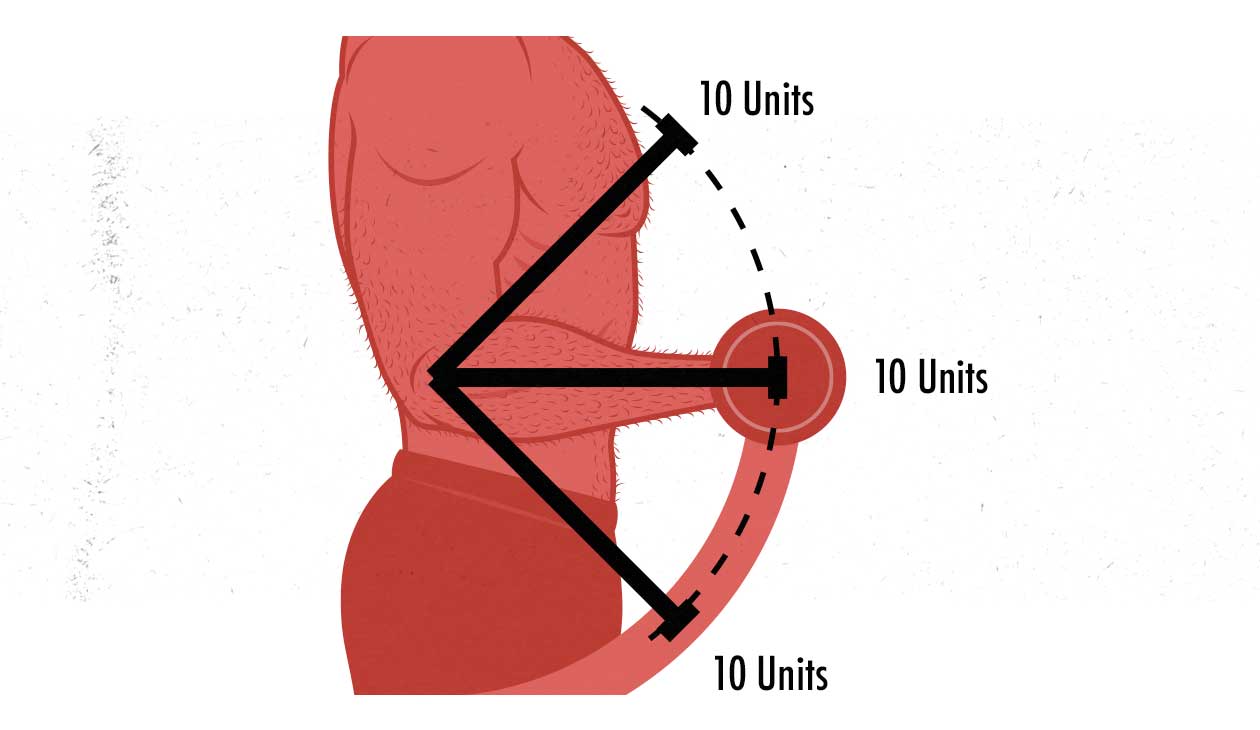

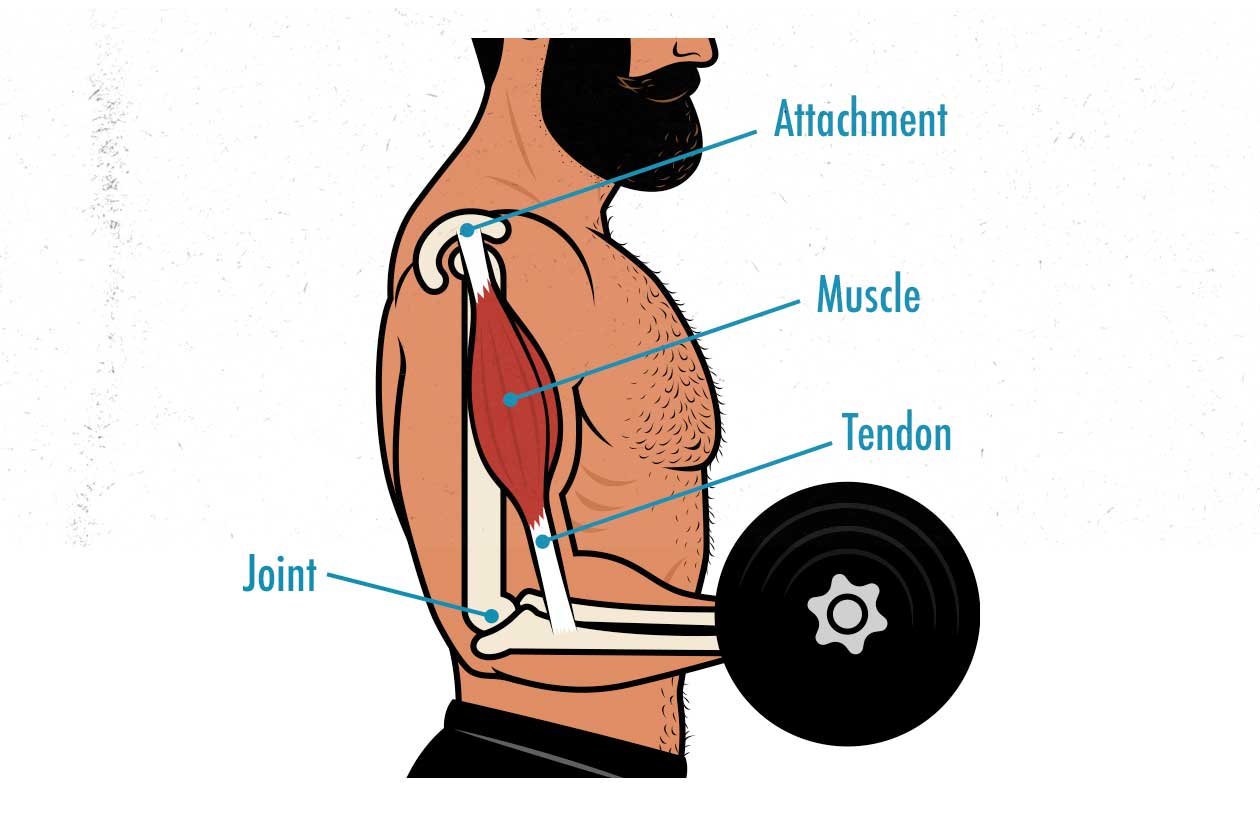

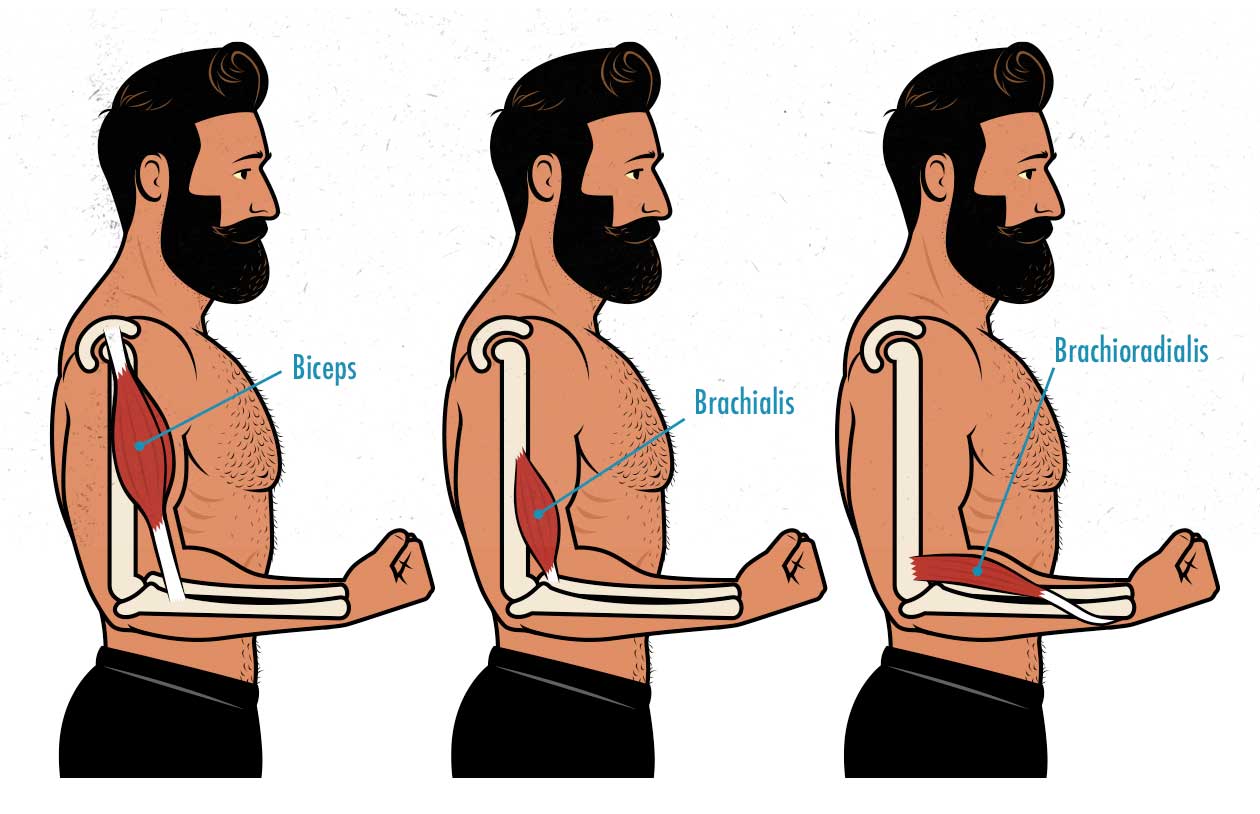

For starters, we need to understand how our muscles attach to our bones and yank on our joints. With the biceps curl, it’s our biceps pulling on our forearm bones to flex our arms at the elbow joint:

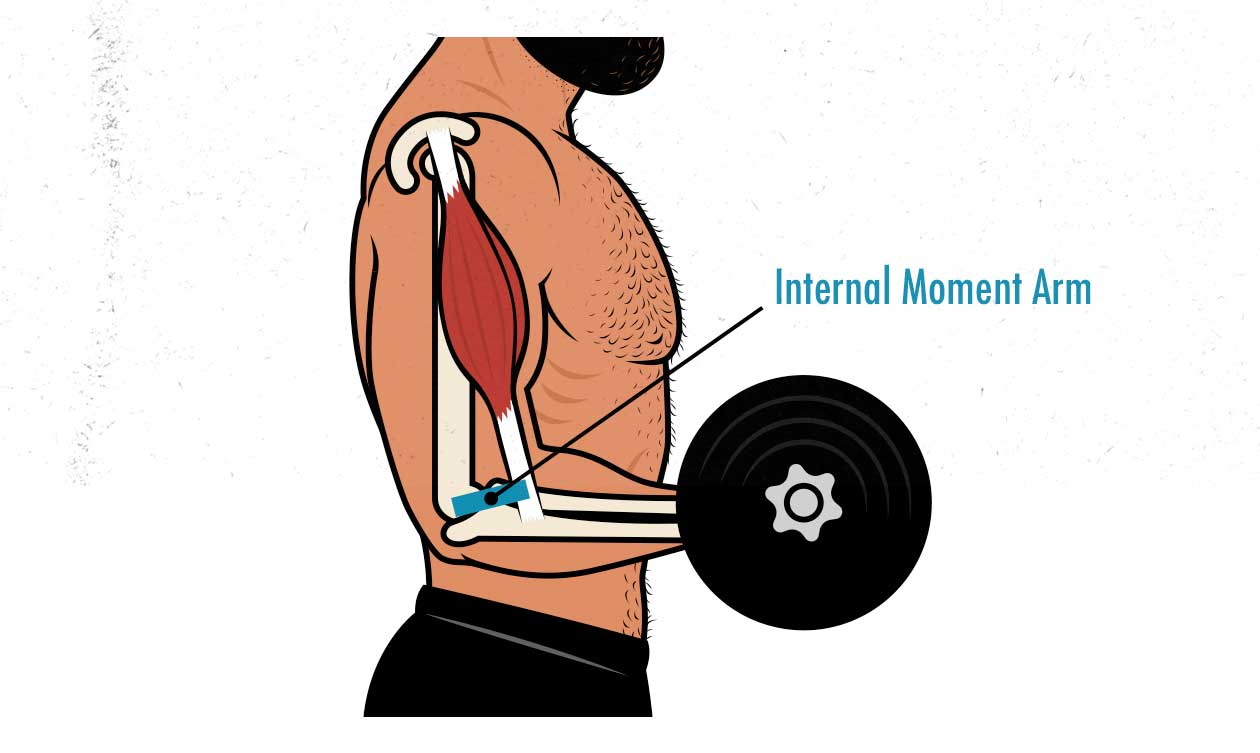

Our internal moments are created by our muscles pulling on our bones. The further away from our joints these internal moments are, the better our leverage will be, similar to how a longer wrench provides better leverage than a shorter one.

Internal Moments & Strength Genetics

Just like with external moments, there’s a genetic component here, too. Using an exaggerated example, if one guy had internal moments that were 50% longer, then he’d be able to lift weights that were 50% heavier with biceps that were the same size.

This is a major way that genetics can influence someone’s strength. The further away someone’s tendon insertions are from their joints, the better their leverage will be when lifting weights. They’ve got longer wrenches, so to speak, allowing them to tighten bolts more easily.

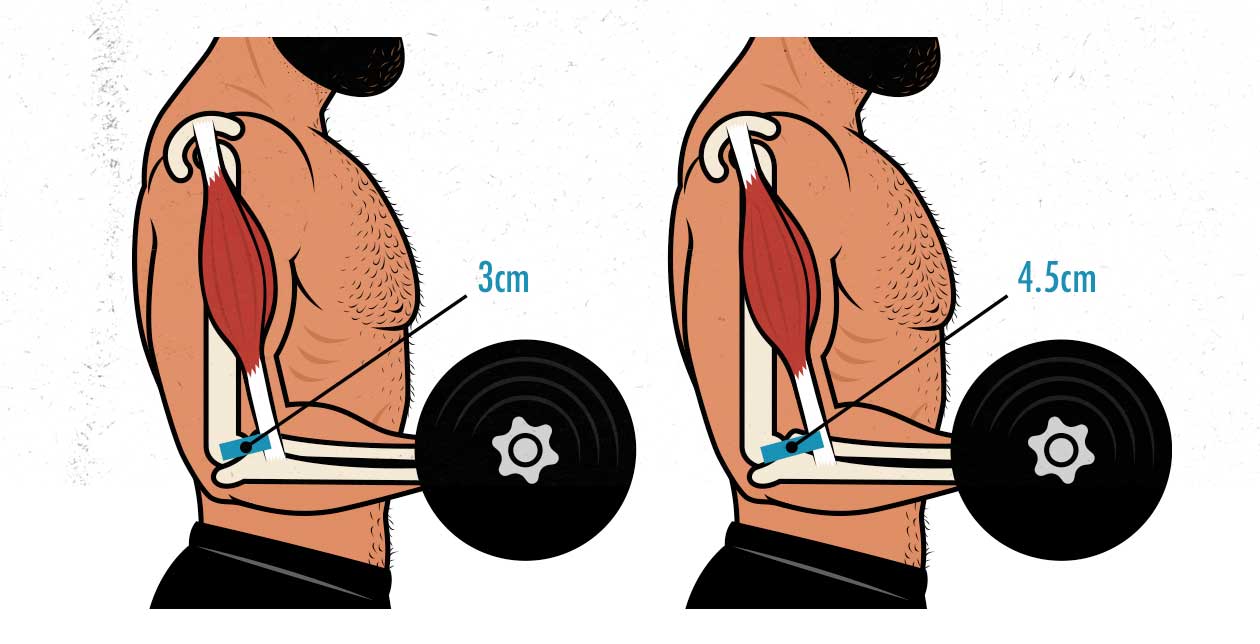

I tried to dig around in the research to see how much human variation there was with our biceps tendon insertions, but I couldn’t find anything. I did find one for our knee joint, though, where our internal moments vary between 4–6cm (study). That means if we took two guys with equal leg size, one might be able to lift 50% more weight than the other! This is one of the many reasons why judging someone’s expertise, methods, or work ethic by much weight they can lift is so foolish. The stronger lifter might not be working harder or smarter, they might just have better leverage.

Now, to be clear, most of us have average internal moments. With our biceps, most of our tendons will insert around 4cm away from our elbow joint. It will vary a little bit, sure, but not by a huge degree. Among our friends, our muscle size will probably correlate fairly closely with our strength. On the other hand, if we’re looking at people who are famous for being strong, then we’re generally looking at genetic outliers.

Anyhow, there’s nothing we can do to change our insertion points, and although they’ll certainly change the amount of weight we can lift, they won’t change the degree to which we can stimulate our muscles. Going back to the exaggerated example above, the guy with shorter internal moments would be weaker, sure, but that wouldn’t necessarily be a hypertrophy disadvantage. He’ll still be able to challenge his biceps, he’ll just need to use lighter weights. The downside, though, is that his supporting muscles (such as his upper back muscles) might not be worked as hard. And so he might benefit from more accessory work. This may be why some people respond better to minimalist workout programs than others.

Even so, no matter how bad our powerlifting and strength genetics are, we can still build muscle just fine, we just need to find a bulking program that suits us.

Internal Moments & Strength Curve

Just like our external moments, our internal moments change throughout the range of motion. When we’re doing barbell curls, our biceps have the best leverage when our elbows are at around 90 degrees, which is the hardest part of the lift:

That means that a regular barbell curl actually has a pretty good strength curve for building muscle. It’s not perfect—we’ll still typically fail at that midpoint—but it’s pretty good!

It gets more interesting, too. We have different muscles working together to flex our arms, each with varying internal moments, and so they’re each strongest at different parts of the range of motion.

For example, our biceps have proportionally greater strength at the bottom of the lift, whereas our forearms (brachioradialis) have proportionally greater strength at the top. And so by using a larger range of motion, we get to stimulate a wider variety of muscles.

Our wrist position can also change our internal moment arms while curling. If we use an overhand (pronated) grip, our biceps lose their leverage, whereas if we use an underhand (supinated) grip, we get to take advantage of larger internal moments (study). This is one reason why we’re stronger when curling with an underhand (or slightly angled) grip. This helps explain why chin-ups are better for our biceps than pull-ups, and why underhand barbell rows are better for our biceps than overhand barbell rows.

If we always use an underhand grip, though, then our forearm and brachialis muscles might lag behind our biceps, and so, again, it’s good to have a smart combination of bulking lifts.

As mentioned above, though, we have a full article on understanding strength curves as they relate to muscle growth.

Key Takeaways

When building a bulking routine, we want to challenge all of our muscles enough to provoke muscle growth. More than that, even. We want to challenge the different regions of our muscles in order to provoke as much muscle growth as possible in every muscle.

Then, with internal moments, the main thing to understand is that both our external and internal moments play against one another to create our leverage while lifting, and some lifts are better for that than others. Biceps curls are pretty good, which is why they make such a great example.

There are a few ways to get more muscle growth out of our lifts:

- Choose lifts that are harder through a larger range of motion. For example, chin-ups are fairly challenging through a large range of motion, whereas pull-ups are only challenging at the very top of a much smaller range of motion.

- Choose lifts that engage more overall muscle mass. For example, front squats work our quads and glutes just as much as back squats, but they’re also challenging enough on our spinal erectors to stimulate upper back growth. Similarly, while sumo deadlifts are mainly hard on our hips, conventional deadlifts are also hard on our entire posterior chains.

- Use a variety of different lifts with different limiting factors, and with different strength curves. For example, we might want to do both barbell curls and underhand rows for our biceps. And we might want to do both chin-ups and rows for our upper backs.

- We can’t let these details distract us from getting stronger at the big compound lifts.

Just to reiterate that final point, this isn’t to say that we need to be super finicky with our lift selection. Many of the popular compound lifts are already great for muscle growth. However, they’re often optimized for powerlifting performance, not for building muscle, gaining strength, improving our health, or becoming better looking. So if our main goal is to bulk up, then there are ways we can adjust our lift selection and technique to build more muscle.

We have articles breaking down all five of the best bulking lifts:

- The Deadlift Guide (for Bulking)

- The Squat Guide (for Bulking)

- The Bench Press Guide (for Bulking)

- The Overhead Press Guide (for Bulking)

- The Chin-Up Guide (for Bulking)

Or if you want a customizable bulking program (and full guide) that builds these principles in, then check out our Outlift Intermediate Bulking Program. If you liked this article, you’ll love the full program.